Erysipelas

Erysipelas, also known as St. Anthony's fire, is a relatively common bacterial infection of the superficial layer of the skin (upper dermis), extending to the superficial lymphatic vessels within the skin, characterized by a raised, well-defined, tender, bright red rash typically on the face or legs, but can occur anywhere in skin. It is a form of cellulitis and is potentially serious.[1][2][3]

| Erysipelas | |

|---|---|

| Other names | Ignis sacer, holy fire, St. Anthony's fire |

| |

| Erysipelas of the face due to invasive Streptococcus | |

| Pronunciation |

|

| Specialty | Dermatology, Infectious disease |

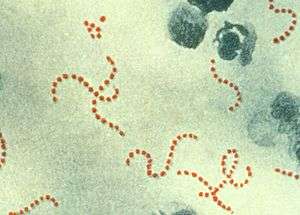

Erysipelas is usually caused by the bacteria Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A β-hemolytic streptococci, through a break in the skin such as from scratches or an insect bite. It is more superficial than cellulitis, and is typically more raised and demarcated.[4] The term is from Greek ἐρυσίπελας, meaning "red skin".[5]

In animals, erysipelas is a disease caused by infection with the bacterium Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae. The disease caused in animals is called Diamond Skin Disease, which occurs especially in pigs. Heart valves and skin are affected. Erysipelothrix rhusiopathiae can also infect humans, but in that case the infection is known as erysipeloid.

Signs and symptoms

Symptoms often occur suddenly. Affected individuals may develop a fever, shivering, chills, fatigue, headaches, vomiting and be generally unwell within 48 hours of the initial infection.[1][2] The red plaque enlarges rapidly and has a sharply demarcated, raised edge.[4][6] It may appear swollen, feel firm, warm and tender to touch and may have a consistency similar to orange peel.[2] Pain may be extreme.[6]

More severe infections can result in vesicles (pox or insect bite-like marks), blisters, and petechiae (small purple or red spots), with possible skin necrosis (death).[6] Lymph nodes may be swollen, and lymphedema may occur. Occasionally, a red streak extending to the lymph node can be seen.

The infection may occur on any part of the skin, including the face, arms, fingers, legs and toes; it tends to favour the extremities.[1] The umbilical stump and sites of lymphoedema are also common sites affected.[6]

Fat tissue and facial areas, typically around the eyes, ears, and cheeks, are most susceptible to infection. Repeated infection of the extremities can lead to chronic swelling (lymphoedema).[2]

- Erysipelas (ear)

- Erysipelas (arm)

Erysipelas (leg)

Erysipelas (leg) Recurrent erysipelas

Recurrent erysipelas

Cause

Most cases of erysipelas are due to Streptococcus pyogenes, also known as group A β-hemolytic streptococci, less commonly by group C or G streptococci and rarely due to Staphylococcus aureus. Newborns may contract erysipelas due to Streptococcus agalactiae, also known as group B streptococcus or GBS.[6]

The infecting bacteria can enter the skin through minor trauma, human, insect or animal bites, surgical incisions, ulcers, burns and abrasions. There may be underlying eczema, athlete's foot, and it can originate from streptococci bacteria in the subject's own nasal passages or ear.[6]

The rash is due to an exotoxin, not the Streptococcus bacteria, and is found in areas where no symptoms are present; e.g., the infection may be in the nasopharynx, but the rash is found usually on the epidermis and superficial lymphatics.

Risk factors

This disease is most common among the elderly, infants, and children. People with immune deficiency, diabetes, alcoholism, skin ulceration, fungal infections, and impaired lymphatic drainage (e.g., after mastectomy, pelvic surgery, bypass grafting) are also at increased risk.[2]

Diagnosis

This disease is diagnosed mainly by the appearance of well-demarcated rash and inflammation. Blood cultures are unreliable for diagnosis of the disease, but may be used to test for sepsis. Erysipelas must be differentiated from herpes zoster, angioedema, contact dermatitis, erythema chronicum migrans of early Lyme disease, gout, septic arthritis, septic bursitis, vasculitis, allergic reaction to an insect bite, acute drug reaction, deep venous thrombosis and diffuse inflammatory carcinoma of the breast.

Differentiating from cellulitis

Erysipelas can be distinguished from cellulitis by two particular features;its raised advancing edge and its sharp borders. The redness in cellulitis is not raised and its border is relatively indistinct.[6] Bright redness of erysipelas has been described as a third differentiating feature.[7]

Erysipelas does not affect subcutaneous tissue. It does not release pus, only serum or serous fluid. Subcutaneous edema may lead the physician to misdiagnose it as cellulitis.[8]

Treatment

Depending on the severity, treatment involves either oral or intravenous antibiotics, using penicillins, clindamycin, or erythromycin. While illness symptoms resolve in a day or two, the skin may take weeks to return to normal.

Because of the risk of reinfection, prophylactic antibiotics are sometimes used after resolution of the initial condition.[2]

Prognosis

The disease prognosis includes:

- Spread of infection to other areas of body can occur through the bloodstream (bacteremia), including septic arthritis. Glomerulonephritis can follow an episode of streptococcal erysipelas or other skin infection, but not rheumatic fever.

- Recurrence of infection: Erysipelas can recur in 18–30% of cases even after antibiotic treatment. A chronic state of recurrent erysipelas infections can occur with several predisposing factors including alcoholism, diabetes, and tinea pedis (athlete's foot).[9] Another predisposing factor is chronic cutaneous edema, such as can in turn be caused by venous insufficiency or heart failure.[10]

- Lymphatic damage

- Necrotizing fasciitis, commonly known as "flesh-eating" bacterial infection, is a potentially deadly exacerbation of the infection if it spreads to deeper tissue.

Epidemiology

Erysipelas may affect any age, but most commonly the very young and the elderly.[1][2]

Erysipelas occurs in isolation and outbreaks are rare. The fall in incidence throughout the mid-20th century is likely attributed to improved hygiene, sanitation and the development of antibiotics. The incidence began to rise in the 1980s. Four out of five cases occur on the legs, although historically the face was a more frequent site.[3]

Notable cases

- Archibald Douglas, 6th Earl of Angus, (d. 1557), Scottish nobleman active in the reigns of James V and Mary, Queen of Scots

- John of the Cross, Spanish saint and priest (d. 1591)

- Michiel de Ruyter, Dutch admiral in the Anglo-Dutch wars, contracted from injuries sustained from a cannonball. (d. 1676)[11]

- Christina, Queen of Sweden (d. 1689)

- Anne, Queen of Great Britain and Ireland (d. 1714)

- Norborne Berkeley, baron de Botetourt, Royal Governor of Virginia (d. 1770)[12]

- Princess Amelia of the United Kingdom, daughter of George III of the United Kingdom (1783–1810)

- Grand Duchess Catherine Pavlovna of Russia, daughter of Tsar Paul I of Russia and wife of King William I of Württemberg (d. 1819)

- William Wirt, United States Attorney General and U.S. presidential candidate (d. 1834)

- Charles Lamb, English writer and essayist (d. 1834)

- Prince Augustus Frederick, Duke of Sussex sixth son and ninth child of King George III (d. 1843)

- Barbara Hofland, English children's writer and novelist (d. 1844)[13]

- Pope Gregory XVI (d. 1846)

- Mary Lyon, American women's education pioneer (d. 1849)[14]

- Marie, Dowager Duchess of Saxe-Coburg-Gotha (d. 1860)

- John Herbert White, youngest son of James S. and Ellen G. White, co-founders of the Seventh-day Adventist church (d. 1860)[15]

- Ralph Bullock, English jockey (d. 1863)

- Frederick VII of Denmark, king of Denmark (d. 1863)[16]

- John Timon, First Roman Catholic Bishop of Buffalo, NY (d. 1867)[17]

- Nehemiah Bushnell, American attorney, railroad president, and politician (d. 1873)

- John Stuart Mill, English political philosopher (d. 1873)[18]

- Marcus Clarke, Australian journalist, poet, playwright and novelist, who wrote "For the Term of His Natural Life", died age 35 (d. 1881) [19]

- John Brown, Scottish personal servant and companion to Queen Victoria (d. 1883)[20]

- Mihai Eminescu, Romanian poet, novelist, journalist (d. 1889)

- Pat Killen, American heavyweight boxer, died at age 29 while in hiding in Chicago from police after assaulting two men (d. 1891)

- Samuel Augustus Ward, American organist, composer, teacher, businessman (d. 1903)[21]

- James Anthony Bailey, American circus ringmaster (d. 1906)[22]

- George Herbert, 5th Earl of Carnarvon (d. 1923), English aristocrat known as the financial backer of the search for and excavation of Tutankhamun's tomb in the Valley of the Kings. His death led to the story of the Curse of Tutankhamun.

- Johann Most was a German-American anarchist politician, newspaper editor, and orator. (d. 1906)

- Miller Huggins, American baseball player and manager (d. 1929)

- Father Solanus Casey, American Capuchin priest declared "blessed" by the Roman Catholic Church (d. 1957)[23]

Chronic, recurrent

- Richard Wagner, opera composer, was prone to outbreaks of erysipelas throughout his adult life. He suffered notably from attacks throughout the year 1855, when he was 42.

Recovered

- Lenin suffered an infection in London, and party leadership was exercised by Martov until he recovered.[24][25][26]

- Ernest Hemingway developed an infection near his left eye after being hit with an oar. He was treated at the Casa di Cura Morgagni in Padua.[27]

Fictional

- In D. H. Lawrence's novel Sons and Lovers one of the major characters in the novel, Paul Morel, dies quickly from the complications of erysipelas in conjunction with pneumonia.[28]

- In Anton Chekhov's 1892 short story "Ward No. 6", erysipelas is among the afflictions suffered by the patients committed to a poorly run mental illness facility in a small town in tsarist Russia.

- In J. G. Farrell's novel The Siege of Krishnapur the Collector, Mr. Hopkins, is afflicted during the Siege and recovers.

- In Mark Twain's Roughing It, mention is made of the disease due to the rarefied atmosphere (Chapter 43).

- In Dashiell Hammett's The Thin Man, the name is used for a pun on the word "ear" (Chapter 22).

- In Willa Cather's One of Ours, the main character, Claude, contracts the disease in "the queerest" way, after being dragged into wire by mules, and the next day continuing to work in the dust. The disease plays a key role in the novel, persuading him to marry Enid after she cares for him in recovery. (Book II, Chapter IV, p. 138).

History

It was historically known as St. Anthony's fire.[3]

Citations

- O'Brian, Gail M. (2019). "Section 1. Diseases and Disorders; Erysipelas". In Fred F. Ferri (ed.). Ferri's Clinical Advisor 2019: 5 Books in 1. Philadelphia: Elsevier. p. 523. ISBN 978-0-323-53042-2.

- Stanway, Amy; Oakley, Amanda; Gomez, Jannet (2016). "Erysipelas | DermNet NZ". dermnetnz.org. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Davis, Loretta S. (9 November 2019). "Erysipelas: Background, Pathophysiology and Etiology, Epidemiology". Medscape.

- Wanat, Karolyn A.; Norton, Scott A. . "Skin & Soft Tissue Infections - Chapter 11 - 2020 Yellow Book | Travelers' Health | CDC". wwwnc.cdc.gov. CDC. Archived from the original on 6 June 2020. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Bhat M, Sriram (2019). SRB's Clinical Methods in Surgery. New Delhi: Jaypee Brothers Medical Publishers. p. 141. ISBN 978-93-5270-545-0.

- Wolff, Klaus; Johnson, Richard (2009). "Part III; Diseases due to microbial agents". Fitzpatrick's Color Atlas and Synopsis of Clinical Dermatology: Sixth Edition. McGraw Hill Professional. p. 609. ISBN 978-0-07-163342-0.

- Stevens, Dennis L.; Bryant, Amy E. (2016), Ferretti, Joseph J.; Stevens, Dennis L.; Fischetti, Vincent A. (eds.), "Impetigo, Erysipelas and Cellulitis", Streptococcus pyogenes: Basic Biology to Clinical Manifestations, University of Oklahoma Health Sciences Center, PMID 26866211, retrieved 8 June 2020

- Spelman, Denis. "Cellulitis and skin abscess: Clinical manifestations and diagnosis". UpToDate. UpToDate. Retrieved 30 July 2019.

- Jorup-Rönström, Christina; Britton, S. (1987-03-01). "Recurrent erysipelas: Predisposing factors and costs of prophylaxis". Infection. 15 (2): 105–106. doi:10.1007/BF01650206. ISSN 0300-8126.

- Nigar Kirmani; Keith F. Woeltje; Hilary Babcock (2012). The Washington Manual of Infectious Disease Subspecialty Consult. Lippincott Williams & Wilkins. ISBN 9781451113648. Page 194

- Entry on Geni.com (Dutch language). Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- "Berkeley, Norborne, baron de Botetourt (1717–1770)".

- Dennis Butts, "Hofland, Barbara (bap. 1770, d. 1844)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography (Oxford, UK: OUP, 2004 Retrieved 20 December 2015, pay-walled.

- Green, Elizabeth Alden (1979). Mary Lyon and Mount Holyoke. Hanover, New Hampshire: University Press of New England. p. 310. ISBN 978-0-87451-172-7.

- "John Herbert White (1860-1860) - Find a Grave".

- Møller, Jan (1994). Frederik 7. En kongeskæbne. Copenhagen: Aschehoug Dansk Forlag. p. 235. ISBN 978-87-11-22878-4.

- Castillo, Dennis (2017-04-14). "Viewpoints: Remembering Buffalo's first Catholic bishop, John Timon, 'a great and good man'". The Buffalo News. Retrieved 2017-04-17.

- Capaldi, Nicholas (2004). John Stuart Mill: a biography. Cambridge, UK: Cambridge University Press. pp. 356. ISBN 978-0-521-62024-6.

- Australian Variety Theatre Archive • http://ozvta.com/practitioners-other-a-l/

- Ridley, Jane (2013). The Heir Apparent: a life of Edward VII, the Crown Prince. New York, NY: Penguin Random House LLC. p. 287.

- America the Beautiful by Lynn Sherr

- Macy, Beth. Truevine. Little, Brown & Co, New York, 2016, page 151.

- Wollenweber, Brother Leo (2002). "Meet Solanus Casey". St. Anthony Messenger Press, Cincinnati, Ohio, page 107, ISBN 1-56955-281-9,

- Rice, Christopher (1990). Lenin: Portrait of a Professional Revolutionary. London: Cassell. ISBN 978-0304318148. pp. 77–78.

- Service, Robert (2000). Lenin: A Biography. London: Macmillan. ISBN 9780333726259. p. 150.

- Rappaport, Helen (2010). Conspirator: Lenin in Exile. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 978-0-465-01395-1 pp. 85–87.

- Hemingway, Mary Welsh (1976). How It Was. London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson. ISBN 0-297-77265-1. p. 236.

- Chapter 6, "Death in the Family" – summary on GradeSaver website. Retrieved 25 January 2016.