Epistle to Philemon

The Epistle of Paul to Philemon, known simply as Philemon, is one of the books of the Christian New Testament. It is a prison letter, co-authored by Paul the Apostle with Timothy, to Philemon, a leader in the Colossian church. It deals with the themes of forgiveness and reconciliation. Paul does not identify himself as an apostle with authority, but as "a prisoner of Jesus Christ", calling Timothy "our brother", and addressing Philemon as "fellow labourer" and "brother."(Philemon 1:1; 1:7; 1:20) Onesimus, a slave that had departed from his master Philemon, was returning with this epistle wherein Paul asked Philemon to receive him as a "brother beloved."(Philemon 1:9–17)

| Epistle to Philemon | |

|---|---|

← Titus 3 | |

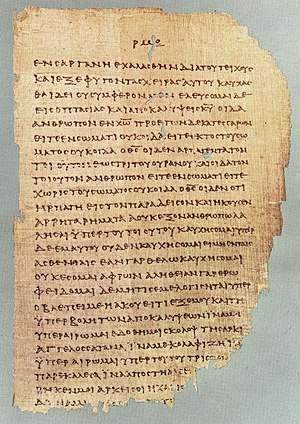

Fragments of the Epistle to Philemon verses 13–15 on Papyrus 87 (Gregory-Aland), from ca. AD 250. This is the earliest known fragment of the Epistle to Philemon. | |

| Book | Epistle to Philemon |

| Category | Pauline epistles |

| Christian Bible part | New Testament |

| Order in the Christian part | 18 |

| Books of the New Testament |

|---|

|

| Gospels |

| Acts |

| Acts of the Apostles |

| Epistles |

|

Romans 1 Corinthians · 2 Corinthians Galatians · Ephesians Philippians · Colossians 1 Thessalonians · 2 Thessalonians 1 Timothy · 2 Timothy Titus · Philemon Hebrews · James 1 Peter · 2 Peter 1 John · 2 John · 3 John Jude |

| Apocalypse |

| Revelation |

| New Testament manuscripts |

| Part of a series of articles on |

| Paul in the Bible |

|---|

.jpg) |

|

See also

|

Philemon was a wealthy Christian, possibly a bishop[1] of the house church that met in his home (Philemon 1:1–2) in Colosse. This letter is now generally regarded as one of the undisputed works of Paul. It is the shortest of Paul's extant letters, consisting of only 335 words in the Greek text.[2]

Content

Greeting and introduction (1–3)

The opening salutation follows a typical pattern found in other Pauline letters. Paul first introduces himself, with a self-designation as a "prisoner of Jesus Christ," which in this case refers to a physical imprisonment. He also mentions his associate Timothy, as a valued colleague who was presumably known to the recipient. As well as addressing the letter to Philemon, Paul sends greetings to Apphia, Archippus and the church that meets in Philemon's house. Apphia is often presumed to be Philemon's wife and Archippus, a "fellow labourer", is sometimes suggested to be their son. Paul concludes his salutation with a prayerful wish for grace and peace.[19]

Thanksgiving and intercession (4–7)

Before addressing the main topic of the letter, Paul continues with a paragraph of thanksgiving and intercession. This serves to prepare the ground for Paul's central request. He gives thanks to God for Philemon's love and faith and prays for his faith to be effective. He concludes this paragraph by describing the joy and comfort he has received from knowing how Philemon has shown love towards the Christians in Colossae.[20]

Paul's plea for Onesimus (8–20)

As a background to his specific plea for Onesimus, Paul clarifies his intentions and circumstances. Although he has the boldness to command Philemon to do what would be right in the circumstances, he prefers to base his appeal on his knowledge of Philemon's love and generosity. He also describes the affection he has for Onesimus and the transformation that has taken place with Onesimus's conversion to the Christian faith. Where Onesimus was "useless", now he is "useful" – a wordplay, as Onesimus means "useful". Paul indicates that he would have been glad to keep Onesimus with him, but recognised that it was right to send him back. Paul's specific request is for Philemon to welcome Onesimus as he would welcome Paul, namely as a Christian brother. He offers to pay for any debt created by Onesimus' departure and expresses his desire that Philemon might refresh his heart in Christ.[21]

Conclusion and greetings (21–25)

In the final section of the letter, Paul describes his confidence that Philemon would do even more than he had requested, perhaps indicating his desire for Onesimus to return to work alongside him. He also mentions his wish to visit and asks Philemon to prepare a guest room. Paul sends greetings from five of his co-workers and concludes the letter with a benediction.[22]

Themes

Paul uses slavery vs. freedom language more often in his writings as a metaphor.[23] At this time slavery was common, and can be seen as a theme in the book of Philemon. Slavery was most commonly found in households. This letter, seemingly, provided alleviation of suffering of some slaves due to the fact that Paul placed pastoral focus on the issue.[24]

Although it is a main theme, Paul does not label slavery as negative or positive. Some scholars see it as unthinkable in the times to even question ending slavery. Because slavery was so ingrained into society that the “abolitionist would have been at the same time an insurrectionist, and the political effects of such a movement would have been unthinkable,"[25] Paul doesn’t question it in this epistle. Paul may have envisioned slavery as a fixed institution. He was not questioning the “rightness or wrongness” of it. Paul did however view slavery as a human institution, and believed that all human institutions were about to fade away.[25] This may be because Paul had the perspective that Jesus would return soon. Paul viewed his present world as something that was swiftly passing away.[26] This is a part of Pauline Christianity and theology.

When it comes to Onesimus and his circumstance as a slave, Paul felt that Onesimus should return to Philemon but not as a slave; rather, under a bond of familial love. Paul also was not suggesting that Onesimus be punished, in spite of the fact that Roman law allowed the owner of a runaway slave nearly unlimited privileges of punishment, even execution.[26] This is a concern of Paul and a reason he is writing to Philemon, asking that Philemon accept Onesimus back in a bond of friendship, forgiveness, and reconciliation. Paul is trying to break through the social barriers dividing people.[26] We see this in many of Paul’s other epistles, including his letters to the Corinthians, delivering the message of unity with others and unity with Christ – a change of identity. As written in Sacra Pagina Philippians and Philemon, the move from slave to freedman has to do with a shift in “standing under the lordship of Jesus Christ”. So in short, Onesimus’ honor and obedience is not claimed by Philemon, but by Christ.

Verses 13–14 suggest that Paul wants Philemon to send Onesimus back to Paul (possibly freeing him for the purpose). Marshall, Travis and Paul write, "Paul hoped that it might be possible for [Onesimus] to spend some time with him as a missionary colleague.... If that is not a request for Onesimus to join Paul’s circle, I do not know what more would need to be said".[27]

Significance

Sarah Ruden, in her Paul Among the People (2010), argues that in the letter to Philemon, Paul created the Western conception of the individual human being, "unconditionally precious to God and therefore entitled to the consideration of other human beings." Before Paul, Ruden argues, a slave was considered subhuman, and entitled to no more consideration than an animal.[28]

Diarmaid MacCulloch, in his A History of Christianity, described the epistle as "a Christian foundation document in the justification of slavery".[29]

In order to better appreciate the Book of Philemon, it is necessary to be aware of the situation of the early Christian community in the Roman Empire; and the economic system of Classical Antiquity based on slavery. According to the Epistle to Diognetus: For the Christians are distinguished from other men neither by country, nor language, nor the customs which they observe... They are in the flesh, but they do not live after the flesh. They pass their days on earth, but they are citizens of heaven. They obey the prescribed laws, and at the same time surpass the laws by their lives.[30]

Pope Benedict XVI refers to this letter in the Encyclic, Spe salvi, highlighting the power of Christianity as power of the transformation of society. In fact Christianity was decisive to the virtual disappearance of slavery during the Middle Ages:

Those who, as far as their civil status is concerned, stand in relation to one an other as masters and slaves, inasmuch as they are members of the one Church have become brothers and sisters—this is how Christians addressed one another... Even if external structures remained unaltered, this changed society from within. When the Letter to the Hebrews says that Christians here on earth do not have a permanent homeland, but seek one which lies in the future (cf. Heb 11:13–16; Phil 3:20), this does not mean for one moment that they live only for the future: present society is recognized by Christians as an exile; they belong to a new society which is the goal of their common pilgrimage and which is anticipated in the course of that pilgrimage.[31]

Notes

- Const. Apost. VII, 46

- Patzia, A. G.; et al. (1994). "Philemon, Letter To". In Hawthorne, Gerald F. (ed.). Dictionary of Paul and His Letters. InterVarsity Press. p. 703. ISBN 978-0851106519.

- Bruce 1984, p. 191.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 270.

- Baur 1875, p. 81.

- Baur 1875, p. 84.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 272.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 267.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 268.

- Callahan 1993, p. 362.

- Callahan 1993, p. 366.

- Callahan 1993, pp. 369ff.

- Witherington 2007, pp. 62–63.

- Mitchell 1995, pp. 145–46.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 266.

- O'Brien 1982, pp. 266-67.

- Bruce 1984, pp. 404–05.

- Lightfoot 1879, p. 281.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 274.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 283.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 303.

- O'Brien 1982, p. 309.

- Foster, Paul. "Philippians And Philemon: Sacra Pagina Commentary." p.174

- Foster, Paul. "Philippians And Philemon: Sacra Pagina Commentary." p.176

- Gaventa, Beverly Roberts, and David L. Petersen. The New Interpreter's Bible: One-Volume Commentary. Nashville: Abingdon, 2010. p.894

- Gaventa, Beverly Roberts, and David L. Petersen. The New Interpreter's Bible: One-Volume Commentary. Nashville: Abingdon, 2010. p.895

- Marshall, I. Howard; Travis, Stephen; Paul, Ian (2011). Exploring the New Testament. Vol. 2: A Guide to the Letters and Revelation (2nd ed.). Downers Grove, Illinois: InterVarsity Press. p. 155. ISBN 9780830869404. Retrieved 25 May 2015.

- Sarah Ruden, Paul Among the People (2010), p. xix.

- Diarmaid MacCulloch, A History of Christianity, 2009 (Penguin 2010, p. 115), ISBN 978-0-14-102189-8

- . The Epistle of Mathetes to Diognetus — Mathetes, Chapter V, v. 1, 287, 288

- Encyclical letter, Spe, Salvy of the Supreme Pontif Benedict XVI to the bishops priests and Deacons Men and Women Religious and all the Lay Faithful on Christian Hopes, Joseph Raztinger, Enciclical, City of Vatican, 2006

References

- Baur, Ferdinand Christian (1875). Paul: His Life and Works. Translated by Rev. A. Menzies (2nd ed.). Williams & Norgate.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bruce, F. F. (1984). The Epistles to the Colossians, to Philemon, and to the Ephesians. New International Commentary on the New Testament. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2510-0.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Callahan, Allen Dwight (1993). "Paul's Epistle to Philemon: Toward an Alternative Argumentum". Harvard Theological Review. 86: 357–76. JSTOR 1509909.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Lightfoot, J. B. (1879). Saint Paul's Epistles to the Colossians and to Philemon. Macmillan.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Mitchell, M. M. (1995). "John Chrysostom on Philemon: A Second Look". Harvard Theological Review. 88: 135–48.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Brien, Peter (1982). Colossians, Philemon. Word Biblical Commentary. Word Books. ISBN 0-8499-0243-6.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Witherington, Ben (2007). The Letters to Philemon, the Colossians, and the Ephesians: A Socio-Rhetorical Commentary on the Captivity Epistles. Eerdmans. ISBN 978-0-8028-2488-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Sources

Further reading

- J. M. G. Barclay, Colossians and Philemon, Sheffield Academic Press, 1997 ISBN 1-85075-818-2

- N. T. Wright, Colossians and Philemon, Tyndale IVP, 1986 ISBN 0-8028-0309-1

External links

Epistle to Philemon | ||

| Preceded by Pastoral Epistle to Titus |

New Testament Books of the Bible |

Succeeded by Epistle to the Hebrews |