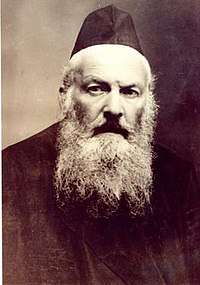

Elchonon Wasserman

Elchonon Bunim[1][2] Wasserman (Hebrew: אלחנן בונים וסרמן; 1874 – 6 July 1941)[3] was a prominent rabbi and rosh yeshiva (dean) in pre-World War II Europe. He was one of Yisrael Meir Kagan's closest disciples and a noted Torah scholar.

Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born | 1874 |

| Died | July 6, 1941 (aged 66–67) |

| Education | Telshe yeshiva |

| Spouse(s) | Michla (nee Atlas) Wasserman |

| Children | Simcha, Naftoli, Dovid |

Biography

Early life and education

Elchonon Wasserman was born in 1874 in Biržai (Birz) in present-day Lithuania to Naftali Beinish, a shopkeeper and Sheina Rakhel.[3] In 1890, the family moved to Bauska (Boisk) in present-day Latvia, and Wasserman, then 15 years old, studied in the Telshe Yeshiva in Telšiai (Telz) under Eliezer Gordon and Shimon Shkop. When Wasserman returned home during vacation, he participated in classes given by Abraham Isaac Kook, who was appointed rabbi of Bauska in 1895.[4] In the summer of 1897, Wasserman met Chaim Soloveitchik at a health resort and "became deeply attached to him and his way of learning."[3] He left Telz and traveled to Brest-Litovsk (Brisk) in present-day Belarus, where he learned under Soloveitchik for two years, thereafter considering him his primary rebbe (teacher and mentor).

Wasserman was married in 1899 to Michla, the daughter of Meir Atlas, rabbi of Salantai (Salant). Wasserman lived in his father-in-law's house for many years and rejected offers of rabbinical posts (including a prestigious rabbinate in Moscow) being afforded the opportunity to learn Torah at home. He did however decide to teach, and together with Yoel Baranchik, he started a mesivta (high school) in Mstislavl (known to Jews as Amtchislav) in 1903 and earned himself a reputation as an outstanding teacher. Prior to 1907, Wasserman heard that another local rabbi wanted to head the mesivta in Amtshilov and he left to avoid an argument, returning to learn in his father-in-law's house.[3] From 1907 to 1910, he studied in the Kollel Kodshim in the Raduń Yeshiva in Radun (Radin), headed by Yisrael Meir Kagan. While at the kollel, Wasserman studied for eighteen hours a day with Yosef Shlomo Kahaneman, who would later become the rosh yeshiva (dean) of the Ponevezh Yeshiva.[3]

Rosh yeshiva

In 1910, with the encouragement of Kagan, Wasserman was appointed rosh yeshiva of the mesivta in Brest-Litovsk, leading its expansion until it was disbanded in 1914 with the outbreak of World War I. With its closing, Wasserman returned to Kagan in Radun.[3] When the Eastern Front reached Radun, however, the yeshiva there was closed, and Wasserman fled to Russia with Kagan.

In 1914, the yeshiva was exiled to Smilavichy (Smilovichi near Minsk) and Wasserman was appointed its rosh yeshiva one year later when Kagan decided to relocate to Siemiatycze (Semiatitch), and together with Yitzchok Hirshowitz (son-in-law of Eliezer Gordon from Telz Yeshiva), was asked to keep Torah alive in Smilavichy.[3]

In 1921, after the war, the Soviet government began permitting Torah scholars to leave Russia. Wasserman moved to Baranovichi, Second Polish Republic (now in Belarus), where he took the lead of Novardok Yeshiva. The yeshiva grew under Wasserman's supervision, and soon had close to 300 students. Copies of notes taken from Wasserman's Torah lectures were passed around many of the yeshivas in Europe, increasing his influence and fame over most of the Torah world.[3] He was one of the leaders of the Agudath Israel movement and was regarded as the spiritual successor of Kagan.

When there was not enough money to buy food for the yeshiva students, Wasserman traveled to the United States to raise money for the yeshiva. He made an impression on many young Jews that he met while he was there. Wasserman returned to Poland, although he knew his life was in danger by doing so. This was partly because he did not want to abandon his students, and partly because he took a dim view of American Jewry. In 1939, just before the Nazi invasion, he even forbade his students from accepting visas to the United States to study at Yeshiva University and what is now the Hebrew Theological College, due to what he perceived as a spiritually dangerous atmosphere in these two institutions.[5]

Death in the Holocaust

When World War II broke out, Wasserman fled to Vilnius (Vilna). In 1941, while on a visit to Kaunas (Kovno), he was arrested by the Nazis with twelve other rabbis and sent to his death.

Wasserman was taken and murdered by Lithuanian collaborators on the 12th of Tammuz, 1941, in the Seventh Fort of Kaunas Fortress. Before he was taken he gave this statement: "In Heaven it appears that they deem us to be righteous because our bodies have been chosen to atone for the Jewish people. Therefore, we must repent now, immediately. There is not much time. We must keep in mind that we will be better offerings if we repent. In this way we will save the lives of our brethren overseas. Let no thought enter our minds, God forbid, which is abominable and which renders an offering unfit. We are now fulfilling the greatest mitzvah. With fire she (Jerusalem) was destroyed and with fire she will be rebuilt. The very fire which consumes our bodies will one day rebuild the Jewish people."

There was no monument,[6] just a marker to the pit where, with others, he was shot.[7]

Wasserman had discouraged emigration to the United States or Palestine, viewing them as places of spiritual danger. He was particularity critical of the Zionist enterprise in Palestine and claimed, "Anti-Semites want to kill the body, but Zionists kill the soul. Better to die than consort with the Zionists."[8]

Family

Wasserman had several sons. Simcha Elazar (1899-1992)[2], his oldest, served as dean of Yeshiva Beth Yehudah in Detroit in the 1940s, founded Yeshiva Ohr Elchonon (later renamed Yeshiva Ohr Elchonon Chabad/West Coast Talmudical Seminary) in Los Angeles, California, in the 1950s, and later founded Yeshiva Ohr Elchonon in Jerusalem. Wasserman's son David survived the Holocaust, remarried and relocated to Brooklyn, NY.[9] Wasserman's other son Naftoli died in the Holocaust.

Works

Wasserman was famous for his clear, penetrating Talmudic analysis. His popular works, essential material in yeshivas around the world, are unique in their approach. He would often quote his rebbe, Chaim Soloveitchik, saying "Producing chiddushim (novel Torah concepts) is not for us. That was only in the power of the Rishonim. Our task is to understand what it says."[3] This approach is evident in his works, which include:

- Kovetz Heoros

- Kovetz Shiurim

- Kovetz Biyurim

- Kovetz Shemuos

- Kovetz Inyanim

- Kovetz Maamarim

- Ikvasa Demeshicha

Wasserman also published the responsa of the Rashba with annotations in 1932. His talmudic novellae appeared in the rabbinic journal Sha'arei Tzion (1929–1934) and in other publications.

References

- Reb Elchonon: The Life and Ideals of Rabbi Elchonon Bunim Wasserman. ISBN 978-0899-06450-5.

- "Rabbi Wasserman, a Pioneer Educator, Dies". The Los Angeles Times. November 5, 1992.

Rabbi Simcha Wasserman, ... Wasserman's father, Elchonon Bunim Wasserman.

- Weekly Biography: Hagaon Harav Elchanan Wasserman Hy"d, Hamodia; 9 July 2008; pg. C3

- Henkin, Eitam (September 22, 2016) "Rav Kook's Attitude Towards Keren Hayesod – United Israel Appeal", The Seforim Blog. Retrieved November 19, 2019.

- Rosenberg, Shmarya (1939). "Rabbi Elchonon Wasserman's Letter Forbidding His Students From Accepting Visas Offered By YU & Skokie Yeshiva". Failed Messiah. Retrieved 5 July 2012.

- (matzeiva) "HaGaon HaRav Simcha Wasserman, zt"l, and Hagaon HaRav Moshe Chodosh, zt"l, Remembered". Five Towns Jewish Home. October 11, 2018.

dream of opening a yeshiva which, in Rav Simcha’s words, would be a matzeiva for his illustrious father, Rav Elchonon Wasserman, who had been murdered by the Nazis in Kovno and had no matzeiva.

- "HaRav Elchanan Bunim Wasserman (Poland) Murdered. Hy"d".

taken to a pit near Kovno and

- Charles Selengut (6 August 2015). Our Promised Land: Faith and Militant Zionism in Israeli Settlements. Rowman & Littlefield Publishers. p. 34. ISBN 978-1-4422-1687-7.

- I Shall Lead You Through the Nights : the Holocaust Memoir of Eva Feldsztein Wasserman, OCLC #841806112 (Margate, NJ:2013), available at https://www.worldcat.org/title/i-shall-lead-you-through-the-nights-the-holocaust-memoir-of-eva-feldsztein-wasserman/oclc/841806112.