Eilabun

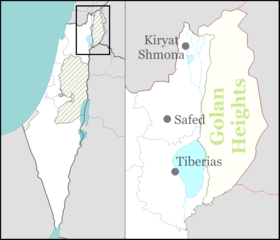

Eilabun (Arabic: عيلبون Ailabun, Hebrew: עַילַבּוּן, עֵילַבּוּ) is an Israeli Arab local council in northern Israel. Located in the Beit Netofa Valley around 15 kilometres (9 miles) south-west of Safed, it had a population of 5,703 in 2018,[1] which is predominantly Christian (70.5%).[2] In 1973, Eilabun achieved local council status by the Israeli government.[3]

Eilabun

| |

|---|---|

| Hebrew transcription(s) | |

| • ISO 259 | ʕeilabbun |

| • Also spelled | Illabun (official) Eilaboun, Ailabun (unofficial) |

| |

Eilabun  Eilabun | |

| Coordinates: 32°50′18″N 35°24′03″E | |

| Grid position | 187/249 PAL |

| Country | |

| District | Northern |

| Government | |

| • Type | Local council (from 1973) |

| Area | |

| • Total | 4,835 dunams (4.835 km2 or 1.867 sq mi) |

| Population (2018)[1] | |

| • Total | 5,703 |

| • Density | 1,200/km2 (3,100/sq mi) |

Etymology

According to the Survey of Western Palestine, the name Eilabun comes from Arabic, meaning "hard, rocky ground."[4] An Israeli theory is that the place was built on the ancient site of "Ailabu" (Hebrew: עַיְלַבּוּ), a possible variation of the name Ein Levon.[5]

History

Pottery remains from the Middle Bronze Age, Iron Age II, Persian, early Roman and from the Byzantine era have been excavated.[6] Rock-cut sarcophagi have been found to the west of the village.[7]

In 2013, excavations were conducted in Eilabun by Gilad Cinamon on behalf of the Israel Antiquities Authority (IAA), during which time remains from the Mamluk era were discovered.[8][9][10]

Elibabun is mentioned as one of the cities associated with one of the twenty-four priestly divisions, the residence of the priestly clan known as Haqoṣ. A stone inscription mentioning the town was discovered in Yemen by orientalist, Walter W. Muller, in 1970, and is believed to have been part of a ruined synagogue, now turned mosque.[11]

Ottoman era

In 1517, the village was incorporated into the Ottoman Empire with the rest of Palestine, and in 1596 it appeared in the Ottoman tax registers as being in the nahiya ("Subdistrict") of Tabariyya, part of Safad Sanjak, with a population of 13 Muslim households. The villagers paid a fixed tax rate of 25% on various agricultural products, including wheat, barley, summer crops, olive trees, cotton, goats and bee hives, in addition to occasional revenues and a tax for a press for olive oil press or grape syrup; a total of 4,500 akçe.[12][13]

In 1838, Aleibun was noted as a Christian village in the Esh Shagur district, which was located between Safad, Acca and Tiberias.[14]

In 1875, the French explorer Victor Guérin found that the village had a population of about 100 Greek Christians, with a "humble" chapel. He noted an excellent water source, and remains (including columns) of old buildings.[15]

In 1881, the PEF's Survey of Western Palestine (SWP) described it as "a stone village, well built, containing about 100 Christian Arab. It is situated on a ridge, surrounded by brushwood, with arable land in the valley. A good spring exists to the west of the village."[16]

A population list from about 1887 showed that Ailbun had about 210 inhabitants; all Catholic Christians.[17]

British Mandate era

In the 1922 census of Palestine, conducted by the British Mandate authorities, Ailabun had a total population of 319, all Christian,[18] increasing in the 1931 census to 404, 32 Muslims and 372 Christians, in a total of 85 houses.[19]

In the 1945 statistics, the population comprised 530 Christians and 20 Muslims,[20] who owned a total of 11,190 dunams of land, while 3,522 dunams of land was public.[21] Of this, 1,209 dunams were for plantations and irrigable land, 2,187 for cereals,[22] while 18 dunams were built-up land.[23]

State of Israel

Israel's Golani Brigade's 12th Battalion captured Eilabun on October 30, 1948—during the 1948 Arab-Israeli War, from the Arab Liberation Army (ALA). After the town's surrender, negotiated by four priests, the commander of the Golani troops selected 13-14 young Arab men of the 'Arab al-Mawasi Bedouin tribe and had them executed, in what became known as the Eilabun massacre, the point being to compel the rest of the tribe to leave.[24] According to historian Benny Morris, those executed were Christians, and the executions were "apparently precipitated by the occupying troops' discovery of the decapitated bodies and one or both heads of two Israeli soldiers captured by ALA troops a month before," [25] The village was then looted.[26] Most of the town's residents were marched out to the Lebanese border, while hundreds fled to nearby gullies, caves and villages.[27][28] As part of an agreement between Archbishop Hakim and the leader of the "Arab Section" in the Israeli Foreign Ministry, the Eliabun exiles in Lebanon were allowed to return in summer of 1949.[27] The village remained under Martial Law until 1966.

On 25 April 2008, six people were injured, two of them sustaining serious wounds, in a brawl which broke out between Druze and Christians near Eilabun.[29] The sectarian conflict was a part of the long running feud between the communities, which began in 2004 in the city of Shefa-'Amr. The April 2008 clash began for an unknown reason as members of the Druze community marched towards the grave site of Jethro, Moses' father-in-law, walking on the main road near the village of Eilabun.[29] The marchers fought with the village residents using guns and stones.[29] The Druze community elders who were present at the scene managed to restore calm.[29] The conflict ended following an official reconciliation between the Druze and Christians in 2009.

Eilabun in films

The Sons of Eilaboun (Arabic: أبناء عيلبون) is a 2007 documentary film by Palestinian artist and film maker Hisham Zreiq, that tells the story of the Nakba in Eilaboun and Eilabun massacre, which was committed by the Israeli army during Operation Hiram in October 1948.

People from Eilabun

References

- "Population in the Localities 2018" (XLS). Israel Central Bureau of Statistics. 25 August 2019. Retrieved 26 August 2019.

- עיילבון 2014

- Eilabun (Israel) Dov Gutterman, FOTW

- Palmer, 1881, p. 121

- HaReuveni, 1999, p. 739

- Feig, 2011, ‘Elabbon, Final report

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 381

- Gosker, 2013, ‘Elabbon

- Cinamon, 2013, ‘Elabbon

- Israel Antiquities Authority, Excavators and Excavations Permit for Year 2013, Survey Permit # A-6783

- Ephraim E. Urbach, Mishmarot u-maʻamadot, Tarbiz (A Quarterly for Jewish Studies) 42, Jerusalem 1973, pp. 304 – 327 (Hebrew); Rainer Degen, An Inscription of the Twenty-Four Priestly Courses from the Yemen, pub. in: Tarbiẕ - A Quarterly for Jewish Studies, Jerusalem 1973, pp. 302–303 (Hebrew)

- Hütteroth and Abdulfattah, 1977, p. 189

- Note that Rhode, 1979, p. 6 writes that the register that Hütteroth and Abdulfattah studied was not from 1595/6, but from 1548/9

- Robinson and Smith, 1841, vol. 3, 2nd appendix, p. 133

- Guérin, 1880, pp. 359-360

- Conder and Kitchener, 1881, SWP I, p. 364

- Schumacher, 1888, p. 174

- Barron, 1923, Table XI, Sub-district of Tiberias, p. 39

- Mills, 1932, p. 82

- Government of Palestine, Village Statistics 1945, p. 12

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 72

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 122

- Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics. Village Statistics, April, 1945. Quoted in Hadawi, 1970, p. 172

- Motti Golani, Adel Manna, Two Sides of the Coin: Independence and Nakba 1948, Institute for Historical Justice and Reconciliation, 2011 p.119.

- Morris, 2008,

- Morris, 2004, pp. 479-480

- Morris, 2004, p. 480

- Benvenisti, 2000, pp. 153-154

- "Druze, Christians clash near Galilee village - Israel News, Ynetnews". Ynetnews.com. 1995-06-20. Retrieved 2013-03-26.

Bibliography

- Barron, J.B., ed. (1923). Palestine: Report and General Abstracts of the Census of 1922. Government of Palestine.

- Benvenisti, M. (2000). Sacred Landscape: The Buried History of the Holy Land Since 1948. University of California Press. ISBN 0-520-21154-5.

- Cinamon, Gilad (2015-11-02). "'Elabbon Final Report" (127). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Conder, C.R.; Kitchener, H.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Memoirs of the Topography, Orography, Hydrography, and Archaeology. 1. London: Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Feig, Nurit (2011-03-06). "'Elabbon Final Report" (123). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Government of Palestine, Department of Statistics (1945). Village Statistics, April, 1945.

- Gosker, Joppe (2013-03-04). "'Elabbon Final Report" (125). Hadashot Arkheologiyot – Excavations and Surveys in Israel. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - Guérin, V. (1880). Description Géographique Historique et Archéologique de la Palestine (in French). 3: Galilee, pt. 1. Paris: L'Imprimerie Nationale.

- Hadawi, S. (1970). Village Statistics of 1945: A Classification of Land and Area ownership in Palestine. Palestine Liberation Organization Research Center.

- HaReuveni, Immanuel (1999). Lexicon of the Land of Israel (in Hebrew). Miskal - Yedioth Ahronoth Books and Chemed Books. ISBN 965-448-413-7.

- Hütteroth, Wolf-Dieter; Abdulfattah, Kamal (1977). Historical Geography of Palestine, Transjordan and Southern Syria in the Late 16th Century. Erlanger Geographische Arbeiten, Sonderband 5. Erlangen, Germany: Vorstand der Fränkischen Geographischen Gesellschaft. ISBN 3-920405-41-2.

- Mills, E., ed. (1932). Census of Palestine 1931. Population of Villages, Towns and Administrative Areas. Jerusalem: Government of Palestine.

- Morris, B. (2004). The Birth of the Palestinian Refugee Problem Revisited. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 978-0-521-00967-6.

- Morris, B. (2008). 1948:A History of the First Arab-Israeli War. Yale University Press.

- Palmer, E.H. (1881). The Survey of Western Palestine: Arabic and English Name Lists Collected During the Survey by Lieutenants Conder and Kitchener, R. E. Transliterated and Explained by E.H. Palmer. Committee of the Palestine Exploration Fund.

- Rhode, H. (1979). Administration and Population of the Sancak of Safed in the Sixteenth Century (PhD). Columbia University.

- Robinson, E.; Smith, E. (1841). Biblical Researches in Palestine, Mount Sinai and Arabia Petraea: A Journal of Travels in the year 1838. 3. Boston: Crocker & Brewster.

- Schumacher, G. (1888). "Population list of the Liwa of Akka". Quarterly statement - Palestine Exploration Fund. 20: 169–191.

External links

- Eilaboun official Website

- Welcome To Eilabun

- Survey of Western Palestine, Map 6: IAA, Wikimedia commons