Early 21st-century civil rights movement

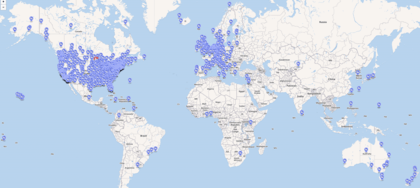

The early 21st-century civil rights movement, also known as the 2020 civil rights movement and the second civil rights movement,[1] is an ongoing movement in the United States calling for the dismantling of systemic racism. The movement originated in the post-civil rights era, gaining momentum in the early 21st century following increased publicity of incidents of police brutality against Black people. Protests occurred in all fifty U.S. states, more than 700 U.S. cities, and over 17 countries worldwide.[2]

| Early 21st century civil rights movement | |

|---|---|

Protesters in Philadelphia on June 2, 2020 | |

| Date | 2020–present |

| Location | United States |

| Caused by |

|

| Goals |

|

| Methods | protesting, social media activism, occupation, rioting |

Protests that sparked in Minneapolis, Minnesota following the death of George Floyd grew across the United States and the world. As subsequent events of police brutality continued to fuel widespread protests, the focus of demonstrations became larger, with many calling for sweeping social reform.[3][4] In June 2020, the movement gained recognition as the largest civil rights movement in history.[2] Leaders of the movement have been likened to Martin Luther King, Jr.,[5] and many have noted the similarities between the current events and the Civil rights movement of the 1950s and 1960s.[6][7][1]

Background

History of police brutality in the United States

In 1992, following the aftermath of the beating of African-American Rodney King, riots occurred in the city of Los Angeles.[8]

Black Lives Matter movement

In 2013, the Black Lives Matter movement began with the use of the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on social media after the acquittal of George Zimmerman in the shooting of Trayvon Martin, a Black teen. The movement garnered national attention in 2014 after the Shooting of Michael Brown, which resulted in protests and unrest in Ferguson, Missouri, and the death of Eric Garner in New York City.[9] This was followed by the deaths of Tamir Rice, Freddie Gray, Sandra Bland, and Philando Castile resulting in additional protests against police brutality. Some began to cite the Black Lives Matter movement as the "birth of a new civil rights movement."[10] Initially, the Black Lives Matter organization was met with criticism, but public approval saw a dramatic increase in 2020.[11][12] The movement gathered further momentum after the death of George Floyd. Black Lives Matter activists have led many of the protests and events throughout the early 21st-century civil rights movement.

Protests of the U.S. national anthem

In 2016, U.S. athletes, led by San Francisco 49ers quarterback Colin Kaepernick, began taking a knee during the national anthem to increase awareness of excess police brutality towards minorities, especially Black people.[13] In an explanation of his protest, Kaepernick stated:

I'm going to continue to stand with the people that are being oppressed. To me, this is something that has to change. When there's significant change and I feel that flag represents what it's supposed to represent, and this country is representing people the way that it's supposed to, I'll stand.

The protests were met with widespread criticism. Commentators shifted the focus of the protest on police brutality to the patriotic aspect of kneeling rather than the meaning behind it, which detracted from Kaepernick's primary goal.[14] Some claimed that the protests were disrespectful to the nation's veterans, while some veterans voiced their support for the athletes.[13]

Coronavirus pandemic

Many felt that Trump Administration's handling of the coronavirus was representative of a kakistocracy, which contributed to distrust of the government and civil unrest.[15]

Economic collapse and high unemployment rates resulting from the COVID-19 pandemic allowed large numbers of citizens to participate in protests.[16] Protesters have been met with criticism, as many have stated that they are contributing to the spread of the coronavirus; however, protesters have argued that they would not be protesting during a pandemic if it were not crucial.[16]

Shooting of Breonna Taylor

On March 13, 2020, Breonna Taylor, a Black ER-technician was shot and killed in her home by police officers.[17] The officers entered on a no-knock warrant, and Taylor's boyfriend, thinking the officers were intruders, fired at the officers. The officers returned fire, killing Breonna Taylor who had been asleep in her bed.[17] The officers were placed on administrative leave, but no charges have been filed against the officers.[17] Taylor's death received renewed attention after the death of George Floyd, with many calling for charges to be brought against the three officers involved.

Run With Maud

Events

Death of George Floyd and initial protests

.jpg)

On May 25, 2020, George Floyd, a 46-year old Black man was killed in Minneapolis, Minnesota when police officer Derek Chauvin knelt on his neck for nearly nine minutes. His death was filmed and spread around the internet, leading to calls for the arrest of Chauvin and other attending officers.[18] Outrage at the video lead to hundreds of protests across the United States and the world.[18]

Some protests became violent, and there were many incidents of looting; however, the majority of protests remained peaceful, with protesters arguing that the looting was not representative of the protests as a whole.[19]

Expansion of protests

As protests against the death of Floyd continued, protesters began demanding large systemic reform and policy changes and developed into a new civil rights movement.[20][21] After charges were brought against Officer Derek Chauvin and the other officers involved in the death of George Floyd, protesters began focusing on other instances of police brutality and called for reform. Numerically, the movement is the largest civil rights movement in history.[2]

Subsequent incidents of police brutality

During the protests against police brutality, numerous additional incidents of police brutality have occurred against both protesters and people of color. On June 2, 2020, Sean Monterrosa, a Latino American man, was killed by a police officer in Vallejo, California, leading to further protests.[22] On June 4, Martin Gugino, a 75-year-old man with a cane suffered a brain injury during the Buffalo police shoving incident.[23] On June 12, police officers shot and killed Rayshard Brooks during a field sobriety test, sparking a wave of protests in Atlanta and across the country.[24]

Intersection with Pride month

The month of June marked the beginning of Pride Month, and as the protests against police brutality continued, they began to merge with the larger movement for LGBT rights. On June 12, 2020, the fourth anniversary of the Pulse nightclub shooting, the Trump Administration and the Department of Health and Human Services' Office for Civil Rights announced that Section 1557 of the Affordable Care Act would no longer define sex discrimination to include gender identity, resulting in the ability for transgender individuals to be discriminated against in healthcare practices.[25] After the deaths of transgender women Dominique Fells and Riah Milton, protesters began holding rallies which called for justice and further investigation of the deaths of the women.[26]

An "All Black Lives Matter" march was held on Hollywood Boulevard, emphasizing that Black transgender individuals are often discriminated against even more heavily than other Black individuals.[27] Many protesters across the United States have called for unity between the LGBT community and the Black Lives Matter movement.[28]

Suspected lynchings

Since May 27, 2020, a woman, a teenage boy, and four men have been found hanging in separate incidents across the United States. All six were Black or Hispanic, leading many to suspect that they were the result of lynchings.[29] Additionally, several nooses have been found hanging from trees across the country, symbolic of the Jim Crow era lynchings.[29]

On May 31, 2020, Malcolm Harsch, a Black man, was found hanging from a tree in Victorville, California, and many worried that he had been lynched. Video evidence later revealed that Harsch had died by suicide. Harsch had been on suicide watch during two recent bookings for minor crimes in San Bernardino jails.[30]

Another Black man, Robert Fuller, was found dead near Poncitlán Square in Palmdale, California, just east of the Palmdale City Hall.[30] Fuller was also found hanging from a tree and his death was initially described by officials as a suspected suicide, but coroner's investigators not yet ruled on the cause of death pending investigation.[30][31] Suspicion increased after Fuller's half-brother, Terron Boone, was killed during a "wild shootout" with police officers.[31]

March on Washington 2020

National Action Network leader Al Sharpton announced plans for a second March on Washington on August 28, 2020, the 57th Anniversary of the first march and Martin Luther King Jr.'s I Have A Dream speech.[32] The organization has requested permits from the National Park Service, but the service is currently shut down due to the coronavirus pandemic.[33] An Instagram account with the name March on Washington 2020 has emerged, claiming to be an organization that is organizing the march, although they have denied affiliation with the National Action Network an Black Lives Matter organizations. This has led to confusion about who is organizing the march and concern about disorganization.[33] The permit submitted by the National Action Network anticipates at least 100,000 participants in the upcoming march.[34]

Movement toward anti-racism

Many have called for the dismantling of racist language. Some have argued replacing the use of African-American with the word "Black", stating that not all Black people in the United States have roots in Africa and that not all Black people identify as African-American.

Characteristics

Grassroots leadership

Use of social media

The movement has seen widespread use of social media to organize and promote its ideas.[16][2] In previous civil rights movements, protests have taken months of organizing, but the development of social media has allowed protest organizers to communicate quickly and effectively with people across the world.[16] Blackout Tuesday was a call for social media users to amplify Black voices so that important information about protests could spread quickly.

Distrust of the government and mainstream media

Prison reform

Many leaders of the movement have called for prison reform and the dismantling of the school-to-prison pipeline as well as the War on Drugs.[2]

Popular reactions

Blackout Tuesday

On June 2, 2020, two music executives Jamila Thomas and Brianna Agyemang called on the music industry to pause normal business through their #theshowmustbepaused initiative. Many artists in the industry observed the day by not posting on social media or releasing new content and ViacomCBS networks, which includes MTV, went dark for 8 minutes and 46 seconds to honor George Floyd, Black Lives Matter, and victims of racism.[35] The movement extended beyond the music industry, with brands and individuals choosing to post a black square in their social media, accompanied by the hashtag #blackouttuesday or #theshowmustbepaused and not post for the remainder of the day to allow black accounts on social media to be amplified.[36][37]

Counter-movements

Several counter-movements have been started against the early 21st-century civil rights movement. The most notable include All Lives Matter and Blue Lives Matter.

Call to defund the police

Many protesters have argued for the defunding of the police, and "Defund the police" has become a rally cry at protests. The idea involves taking money away from law enforcement and putting it toward community resources that prioritize housing, employment, education, and community health.[38]

New York Times Bestseller List

After the death of George Floyd, Black American authors quickly moved to the top of the New York Times Bestseller List.[39] The occasion was the first time that the top 10 entries on the “combined print and ebook non-fiction list” of the bestseller list were primarily titles focusing on race issues in the US.[39] How to Be an Antiracist by Ibram X. Kendi, White Fragility by Robin DiAngelo, and So You Want to Talk About Race by Ijeoma Olou were all featured on the list.[39] The top bestselling books on the Amazon and Barnes and Noble websites were also books focusing on race.[40]

Removal of controversial statues

Autonomous zones

As part of the protests, protesters took over portions of several cities, developing self-proclaimed autonomous zones. The most notable autonomous zone is the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, also known as the CHAZ, in Seattle, Washington. Protesters took over an empty police precinct and declared a portion of the Capitol Hill neighborhood autonomous on June 9, 2020. Within the zone protesters have developed community gardens, taken over empty buildings, and have created numerous works of graffiti art.

An autonomous zone also developed in Minneapolis. The Nashville Autonomous Zone was created on the grounds of the Tennessee State Capitol on June 12, 2020, modeled after the CHAZ. A short-lived autonomous zone also existed in Portland, Oregon.

Response from the entertainment industry

In response to the movement, Netflix and other streaming services made several series and films focusing on the history of racial inequality in America available for free streaming online. When They See Us, 13th, Selma, and Just Mercy.[41] The Bachelor announced that Matt James was cast at the firs Black bachelor on the series after a petition was started to ensure that the next candidate would be Black.[42]

Response from businesses

Many businesses released statements of solidarity and vowed to address racism in their organizations in response to the Black Lives Matter protests. Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben's, Eskimo Pie, Mrs. Butterworth's, and Cream of Wheat all stated that they would be renaming or rebranding their products.[43] NASCAR stated that they would no longer allow Confederate flags to be flown at their races.[44]

Political responses

State and local government response

The protests prompted policy changes in numerous cities across the United States, including banning the use of the chokehold by police officers and reducing funding for police departments.[3] On June 3, 2020 Mayor Eric Garcetti of Los Angeles vowed to defund the Los Angeles Police Department, which was originally expected to receive a $150 million budget increase. On June 8, the city of San Diego voted to create an Office of Race and Equity]]. The city of Seattle announced its intent to defund the Seattle Police Department and on June 15, 2020, the city council unanimously voted to ban the use of tear gas and pepper spray by police officers.[3]

Defunding of the Minneapolis Police Department

On June 5, 2020, the City of Minneapolis banned the use of chokeholds and launched a civil rights investigation on the Minneapolis Police Department in response to the killing of George Floyd.[3] On June 8, nine councilmembers announced that they intended to defund the Minneapolis Police Department by shifting funding toward community-based strategies. The city was among the first to respond to calls by protesters to defund police departments across the nation.[45]

The United States Marine Corps announced a directive banning the Confederate flag with limited exceptions.[46]

Breonna's Law

On June 11, 2020, the Louisville Metro Council voted unanimously to ban no-knock warrants after the passage of Breonna's Law almost three months after Breonna Taylor's death. Breonna's Law requires the use of body cameras by police officers and outlined the rendering of police warrants.[3] At the time, no-knock warrants were legal in every state except for Oregon.[17] After Louisville passed the law, other cities, including Cincinnati, Ohio, began discussing the passage of similar laws.[17]

Black Lives Matter Plaza

On June 5, 2020, Mayor Muriel Bowser renamed a two-block portion of 16th Street NW in Downtown Washington, D.C. "Black Lives Matter Plaza" after the Department of Public Works painted the words "Black Lives Matter" in 35-foot (11 m) yellow capital letters, along with the flag of Washington, D.C., as part of the George Floyd protests.[47][48][48][49] In response, dozens of similar murals were painted on streets across the United States.

Legislative branch response

Juneteenth

Protesters began calling for Congress to make Juneteenth, the day that Black slaves in Texas learned that they were free, a national holiday.[50] On June 19, 2020, Democratic Senators Ed Markey, Cory Booker, Tina Smith, and Kamala Harris proposed a bill to make Juneteenth a national holiday. Republican Senator John Cornyn of Texas, is a cosponsor on the bill.[51]

Executive branch response

The Trump Administration has been largely unsupportive of protesters.

Judicial branch response

On June 10, 2020, the United States Court of Appeals for the Fourth Circuit released an amended opinion in the case of Jones v. City of Martinsburg criticizing police brutality and qualified immunity.

Wayne Jones was killed just over one year before the Ferguson, Missouri shooting of Michael Brown would once again draw national scrutiny to police shootings of black people in the United States. Seven years later, we are asked to decide whether it was clearly established that five officers could not shoot a man 22 times as he lay motionless on the ground. Although we recognize that our police officers are often asked to make splitsecond decisions, we expect them to do so with respect for the dignity and worth of black lives. Before the ink dried on this opinion, the FBI opened an investigation into yet another death of a black man at the hands of police, this time George Floyd in Minneapolis. This has to stop. To award qualified immunity at the summary judgment stage in this case would signal absolute immunity for fear-based use of deadly force, which we cannot accept. The district court’s grant of summary judgment on qualified immunity grounds is reversed, and the dismissal of that claim is hereby vacated.

On June 15, 2020, the United States Supreme Court announced a decision in Bostock v. Clayton County favoring LGBT rights and stating that workplace discrimination based on an individual's gender identity or sexual orientation is prohibited under Title VII of the Civil Rights Act of 1964.[52]

On June 18, the Supreme Court ruled that President Trump could not end the Deferred Action for Childhood Arrivals (DACA) program; however, the Court left room for future action to be taken against the program.[53]

Judge Calvin Johnson, the first African-American elected to the Orleans Parish Criminal District Court, called for the judicial system to become anti-racist.

International responses

Activist Organizations

- American Civil Liberties Union (ACLU)

- The Bail Project

- Black Lives Matter (BLM)

- Black Panther Party

- Black Visions Collective

- Brooklyn Community Bail Fund

- Campaign Zero

- Color of Change

- Equal Justice Initiative

- Minnesota Freedom Fund

- Movement for Black Lives

- National Association for the Advancement of Colored People (NAACP)

- National Action Network

- North Star Health Collective

- Reclaim the Block

Individual Activists

See also

- Civil rights movement (1865-1896)

- Civil rights movement (1896-1954)

- Civil rights movement

- Post-civil rights era in African-American history

Police brutality

References

- Murphy, Chris (June 12, 2020). "A New Civil Rights Movement Is a Foreign Policy Win". Foreign Affairs. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Hart, Gabby (June 11, 2020). "Black Lives Matter protests mark historic civil rights movement, UNLV professor says". NBC News Las Vegas. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Pineda, Khrysgiana (June 18, 2020). "Policy shifts amid national unrest: Louisville passes Breonna's Law; police chokeholds banned in Iowa, Minneapolis". USA Today. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Whitmer, Gretchen; Gilchrist II, Garlin (June 20, 2020). "Taking Action to End Police Brutality". Newsweek. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Downey, Maureen. "'People feeling hopeless lie down and give up. Those with hope stand up, speak up, and protest.'". Atlanta Journal-Constitution. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- De Alba, Adriana (June 5, 2020). "ODU professor explains similarities between today's protests and the Civil Rights Movement". MSN News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Boucher, Ashley (June 20, 2020). "AdChoices People Steve Harvey Calls BLM Protests 'One of the Greatest Movements Since the Civil Rights Movement'". MSN. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "PASSENGER DESCRIBES L.A. POLICE BEATING OF DRIVER, CALLS IT RACIAL". Sun-Sentinel. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Luibrand, Shannnon. "How a death in Ferguson sparked a movement in America". CBS News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Day, Elizabeth (July 19, 2015). "#BlackLivesMatter: the birth of a new civil rights movement". The Guardian. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Druke, Galen, Clare Malone, Perry Bacon Jr., and Nate Silver. June 15, 2020. "Public Opinion Of The Black Lives Matter Movement Has Shifted. What Happens Next?" (podcast). FiveThirtyEight Politics. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Cohn, Nate, and Kevin Quealy. June 10, 2020. "How Public Opinion Has Moved on Black Lives Matter." The Upshot. The New York Times. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- Sandritter, Mark (September 25, 2017). "A timeline of Colin Kaepernick's national anthem protest and the athletes who joined him". SB Nation. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Graham, Bryan Armen; Carpenter, Les (September 16, 2016). "Colin Kaepernick's critics are ignoring the target of his protest". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Bates, Karen Grigsby (June 3, 2020). "1968-2020: A Tale Of Two Uprisings". NPR. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Gitt, Tammie (June 12, 2020). "Beyond the Protests: 'Things have been building up for a long time' to spark protest movement". The Sentinel. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Mencarini, Matt (June 15, 2020). "Cincinnati, other cities look to Breonna's Law after Louisville bans no-knock warrants". USA Today. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Barker, Kim; Eligon, John; Oppel Jr., Richard A.; Furber, Matt (June 4, 2020). "Officers Charged in George Floyd's Death Not Likely to Present United Front". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Chicago Protesters Say Looting Overshadows Peaceful Demonstrations". NPR. June 2, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- McQuilkin, Hilary; Chakrabarti, Meghna (June 9, 2020). "America's Call For A Modern-Day Civil Rights Movement". WBUR. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Sugrue, Thomas J. (June 11, 2020). "2020 is not 1968: To understand today's protests, you must look further back". National Geographic. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Cassidy, Megan (June 19, 2020). "Sean Monterrosa, SF man killed in controversial Vallejo police shooting, laid to rest". San Francisco Chronicle. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Miller, Ryan W.; Culver, Jordan; Robinson, David; Hauck, Grace; Taddeo, Sarah. "2 Buffalo cops charged with assault after video shows officers shoving 75-year-old man to the ground". USA TODAY. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 6, 2020.

- Bynum, Russ; Anderson, Brynn (June 14, 2020). "Atlanta police chief resigns after fatal police shooting". Associated Press. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Avery, Dan (June 13, 2020). "Biden says Trump's 'cruelty knows no bounds' for revoking transgender healthcare protections during Pride month". Insider. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Colarossi, Natalie (June 16, 2020). "18 photos show how Pride and Black Lives Matter supporters are rallying together for change". Insider. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Branson-Potts, Hailey; Stiles, Matt (June 15, 2020). "All Black Lives Matter march calls for LGBTQ rights and racial justice". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Callum-Penso, Lillia (June 20, 2020). "Upstate Pride SC UNITY event urges collaboration and action to fight systemic racism, injustice". Greenville News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Lee, ArLuther (June 17, 2020). "6 people of color have died in recent string of hangings across country". Herald-Mail Media. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Rokos, Brian (June 20, 2020). "Video shows Black California man was not lynched, but hanged himself". The Mercury News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Lau, Maya; Tchekmedyian, Alene; Miller, Leila; Hamilton, Matt; Dorany, Pineda (June 19, 2020). "A search for answers after deputies kill brother of Black man found hanging from tree". The Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Register for NAN's March on Washington: Get Your Knee Off Our Necks!". National Action Network. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Williams, Elliot C. (June 9, 2020). "There's A March On Washington Scheduled For Late August, And A Lot Of Confusion About Who's Organizing It". DCist. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Here are the proposed plans for the 2020 March on Washington". WUSA. June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Gonzales, Sandra (June 2, 2020). "Music industry leaders vow to pause business for a day in observation of Blackout Tuesday". CNN. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Griffin, Andrew (June 2, 2020). "BLACKOUT TUESDAY: WHAT DO INSTAGRAM BLACK SQUARES MEAN – AND HOW CAN YOU TAKE PART?". The Independent. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Curtis, Charles (June 2, 2020). "What is Blackout Tuesday? The social media trend and controversy around it, explained". USA Today. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Levin, Sam (June 6, 2020). "What does 'defund the police' mean? The rallying cry sweeping the US – explained". The Guardian. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Evelyn, Kenya (June 11, 2020). "Black US authors top New York Times bestseller list as protests continue". The Guardian. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Harris, Elizabeth A. (June 5, 2020). "People Are Marching Against Racism. They're Also Reading About It". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Huff, Lauren (June 18, 2020). "When They See Us, 13th available for free on Netflix ahead of Juneteenth". Entertainment Weekly. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Perez, Lexy (June 17, 2020). "Rachel Lindsay Talks Black 'Bachelor' Casting, Hannah Brown Controversy". The Hollywood Reporter. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Tyko, Kelly (June 19, 2020). "Eskimo Pie, Aunt Jemima, Uncle Ben's and Cream of Wheat are changing. Are the Washington Redskins next?". USA Today. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Levenson, Michael (June 10, 2020). "NASCAR Says It Will Ban Confederate Flags". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Andone, Dakin; Maxouris, Christina; Campbell, Josh (June 8, 2020). "Minneapolis City Council members intend to defund and dismantle the city's police department". CNN. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Freiman, Jordan (June 6, 2020). "U.S. Marine Corps to remove displays of Confederate battle flag". CBS News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Johnson, Ted (June 6, 2020). "DC Mayor Chides Donald Trump at Largest Protest Since Death of George Floyd: 'We Pushed the Army Away from Our City'". Deadline. Archived from the original on June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Aratani, Lauren (June 6, 2020). "Washington Mayor Stands Up to Trump and Unveils Black Lives Matter Mural". The Guardian. London. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 7, 2020.

- Mamiit, Aaron (June 9, 2020). "Google Maps, Bing Maps add marker for Black Lives Matter Plaza in Washington D.C." Digital Trends. digitaltrends.com. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Whitfield, Jayla (June 19, 2020). "Calls increase to make Juneteenth a national holiday". Fox News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Shabad, Rebecca (June 19, 2020). "Senators propose bill to make Juneteenth a federal holiday". NBC News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Fitzsimons, Tim (June 16, 2020). "Supreme Court sent 'clear message' with LGBTQ ruling, plaintiff Gerald Bostock says". NBC News. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Gerstein, Josh; Rainey, Rebecca (June 18, 2020). "Supreme Court rejects Trump effort to end DACA". Politico. Retrieved June 20, 2020.