Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone

The Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ),[5] also known as Free Capitol Hill,[6][7] the Capitol Hill Occupied Protest,[8][9] and the Capitol Hill Organized Protest (CHOP)[10][11][12][13] is an occupation protest and self-declared autonomous zone[1] in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle, Washington. The zone, originally covering six city blocks and a park,[14][15] was established by George Floyd protesters on June 8, 2020 after the Seattle Police Department (SPD) vacated its East Precinct building.[2]

Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone | |

|---|---|

| Capitol Hill Organized Protest | |

Aerial view of zone showing Pine St. & 10th Ave. | |

| Nickname(s): CHAZ or CHOP | |

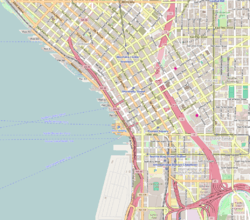

Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone The zone's location in the Capitol Hill neighborhood of Seattle | |

| Coordinates: 47°36′54.5″N 122°19′2.83″W | |

| Status | Self-declared autonomous zone[1] |

| Established | June 8, 2020[2] |

| Government | |

| • Type | Consensus decision-making by daily meeting of protesters[3][4] |

Local governance in the zone was decentralized, with the goal of creating a neighborhood without police. On June 9, 2020, protesters demanded rent control, the reversal of gentrification, the abolition or defunding of police, funding of community health, and releasing prisoners serving time for marijuana-related offenses or resisting arrest, with expungement of their records.[16][17]

Reactions to the zone varied through the political spectrum. President Donald Trump referred to the occupants as "ugly Anarchists" and called for the governor of Washington and the mayor of Seattle to "take back" the zone,[4] while Mayor Jenny Durkan on June 11 described the zone as "four blocks in Seattle that is more like a block party atmosphere. It's not an armed takeover. It's not a military junta. We will make sure that we will restore this but we have block parties and the like in this part of Seattle all the time ... there is no threat right now to the public."[18] On June 14, USA Today confirmed a festive atmosphere, comparing the protest to a miniature version of Burning Man.[19] The following week, on June 22, the Associated Press stated "[a]t night, however, the atmosphere has become more charged, with demonstrators marching and armed volunteer guards keeping watch."[20]

Following the zone's founding, SPD Chief Carmen Best said that the police department was looking at different approaches to "reduce [their] footprint" in the Capitol Hill neighborhood[21] but later said that officials were working to return police officers to the precinct. She stressed the "need to have officers responding to calls in a timely fashion. And with the occupation that's taking place, we're not able to do so in a timely way."[22]

On June 12, Black Lives Matter protesters were reportedly negotiating with local officials over terms for leaving the zone.[23] Four days later, the zone's roadblocks were replaced and moved,[24] allowing for emergency service vehicles to pass through and decreasing CHAZ's size to three blocks.[25] After shootings in or near the zone resulted in injuries and one death, Durkan stated that the SPD would return to the East Precinct "peacefully and in the near future".[26][27] On June 24, a statement tweeted by an account titled "Capitol Hill Occupied Protest (Official Account)" said that "the CHOP project is now concluded,"[28][29] though protesters interviewed in the zone were unaware of the announcement or of any plans to disband CHOP.[30] Multiple sources reported that, after the weekend of June 20, the zone's footprint shrank[30][31] and some occupiers left.[32][33] City transportation crews arrived in the zone on the morning of June 26 to remove barricades set up by demonstrators, but halted work when a protester laid in the street to block their heavy equipment.[34] That afternoon, Durkan met with a group of protesters. After the meeting, the city's plan was reported to be to remove most of the CHOP barricades by the end of June 28, limiting the CHOP area to the East Precinct building and the street directly in front of it.[35][36] On June 27, one day after KOMO-TV reported the number of protesters remaining in the zone had "dwindled to a few dozen",[37] The Wall Street Journal estimated several hundred demonstrators remained.[38]

Background

Capitol Hill is a district in downtown Seattle known for its prominent LGBT and counterculture communities. The district was previously a center for other mass protests,[39] such as the 1999 Seattle WTO protests[40] and Occupy Seattle.[41]

Protests over the killing of George Floyd and police brutality began in Seattle on May 29, 2020.[42] For nine days there were street clashes involving protesters, the Seattle Police Department (SPD), Washington State Patrol, and Washington National Guard.[43] On June 5, Mayor Jenny Durkan and SPD Chief Carmen Best announced a 30-day ban on the use of tear gas.[44] Protests eventually coalesced around the SPD's East Precinct building, where the SPD used aggressive dispersal tactics, including blast balls,[45] flash bangs, and pepper spray.[46] By June 7, police were placing barricades around the precinct and boarding up its windows.[47] Later that day, a car drove into a crowd of protesters, after which the driver shot a protester who had attempted to disarm him, before surrendering to police.[48] The crowd outside the precinct grew and police, reporting that protesters were throwing bottles, rocks, and fireworks, were authorized to resume the use of tear gas shortly after midnight.[49] Over 12,000 complaints were filed about the police response to the demonstrations, and members of the Seattle city council questioned how many weapons had in fact been thrown at the police.[49]

The following afternoon, in a "police retreat",[7] the SPD abandoned the East Precinct. Protesters, initially suspicious of the police's motives, moved into the area, erected street barricades at a one-block radius from the station, and declared the area "Free Capitol Hill".[7] Days after the event, it remained unclear who, if anyone, made the decision to retreat from the East Precinct.[50] On June 24, The Seattle Times reported that Mayor Durkin attributed the decision to an unnamed "on-scene commander for SPD".[51]

Territory

.png)

The zone was centered around the East Precinct building, a police precinct from which the police retreated on June 8, 2020.[2][52] It stretched north to East Denny Way, east to 13th Avenue, south to East Pike, and west to Broadway. The entirety of Cal Anderson Park fell inside of the zone.[53] Protesters used blockades and fences to construct staggered barricades at intersections.[52] The entrance of the zone's territory is marked by a barrier reading "You Are Entering Free Capitol Hill."[7] Other signs declared "You are now leaving the USA."[14] Spray paint renamed the occupied police station as the "Seattle People's Department East Precinct" amid anarchist symbols and graffiti.[15]

On June 16, the city and representatives of CHAZ agreed on a footprint for the zone. The new layout was posted on Mayor Durkan's blog following the agreement.[54] The blog entry states the reasoning for the agreement between the two parties: "The City is committed to maintaining space for community to come to together, protest and exercise their first amendment rights. Minor changes to the protest zone will implement safer and sturdier barriers to protect individuals in this area."[55] As part of the agreement the city agreed to remove the old barriers and replace them with concrete along the new agreed-upon zone boundaries.[54] On June 18, NPR reported, "Nobody inside the protest zone thinks a police return would end peacefully. Small teams of armed anti-fascists are also present, self-proclaimed community defense forces who say they're ready to fight if needed but that de-escalation is preferred."[56]

Internal governance

The Seattle Times referred to demonstrations in the area as the "Capitol Hill Occupied Protest" and the "Capitol Hill Organized Protest" (CHOP),[9] with NBC News saying CHAZ is "part protest, part commune".[5] Reports described the zone's structure as a cross between Occupy Wall Street and an independent student housing cooperative. Occupants said their intentions are to create a neighborhood without police and a society where the police are no longer necessary.[58]

Occupants of the zone favored consensus decision-making instead of designating leaders who, according to one protester, can be "taken out"—killed or arrested.[3] However, City Journal on June 10, 2020, reported that radical activist and former mayoral candidate Nikkita Oliver held a major role within in the zone.[15] Seattle-based hip hop artist Raz Simone was reported by CNN to be the zone's de facto leader,[28] with some publications accusing him of acting in the manner of a "warlord."[59][60] Protesters held frequent town halls to decide strategy and make plans.[4] Seattle officials saw no evidence of Antifa umbrella groups organizing in the zone.[61] On June 15, SPD Chief Best said, "There is no cop-free zone in the city of Seattle." Best indicated officers would go into the zone if there were threats to public safety: "I think that the picture has been painted in many areas that shows the city is under siege", she added. "That is not the case."[62]

KUOW reported that pavement at one intersection was repainted on June 14 with the new acronym CHOP following a discussion in which many of the most active participants had agreed to officially revise the name to the Capitol Hill Organized Protest for better accuracy.[63] Other media reported the name change on June 15 (King5 and The Stranger), June 16 (Vox), and June 17 (Crosscut).[64][65][11][66]

Demands

On June 9, a blog post containing a list of 30 demands appeared on Medium, including abolition of the Seattle Police Department and the court system; defunding the SPD and reallocating those funds to community health; banning police use of firearms, batons, riot shields, and chemical agents; immediately releasing prisoners serving time for marijuana-related offenses or resisting arrest, with expungement of their records; mandatory retrials for people of color who are serving sentences for violent crimes; and prison abolition. Other demands included reforming education to increase the focus on black and Native American history; free college; and free public housing.[16][17] There was reportedly internal debate within the area over how many demands the commune should be putting forward, as some believed that the protests were the start of a larger revolution while others believed police brutality should stay the immediate focus.[67]

On June 10, approximately 1,000 protesters marched to the Seattle City Hall demanding the resignation of Mayor Durkan.[68][69]

Security

Protesters accepted the open carry of firearms as a provision of safety.[70] Members of the self-described anti-fascist, anti-racist, and pro-worker Puget Sound John Brown Gun Club (PSJBGC) were reported on June 9 as carrying rifles in the zone.[7][71] Although the zone fell within[72] the restricted area subject to Mayor Durkan's May 30 emergency order prohibiting the use of weapons including guns,[73] her ban did not mandate enforcement.[72] The Washington Post reported on June 12 that PSJBGC was on site but with no weapons visible,[74] and USA Today the same day reported that "no one appeared armed with a gun".[75] Reporters from a Tacoma-based Fox affiliate were chased out of the zone by occupants on June 9.[76]

Volunteers within the area formed an informal group to provide security, with an emphasis on de-escalation tactics and preventing vandalism.[77][78] On June 16, Seattle's KIRO-TV quoted an eight-year tenant of an apartment near the East Precinct as saying, "We are just sitting ducks all day. Now every criminal in the city knows they can come into this area and they can do anything they want as long as it isn't life-threatening, and the police won't come in to do anything about it."[79] Frustrated by blocked streets, criminal behavior, and lawlessness, some residents temporarily moved out and others installed security cameras. A man who said he "100 percent" supports the protest told KOMO-TV: "I don't even feel safe anymore."[80] According to The Stranger, on June 18, a volunteer medic intervened during a sexual assault within a tent inside the occupied park area; the alleged perpetrator was arrested and held on $75,000 bail.[81]

On June 25, KOMO-TV reported that Tusitala "Tiny" Toese, a member of the Proud Boys far-right group, was arrested for violating his probation after video showed him allegedly assaulting a man in the CHOP.[82][83]

Shootings

On June 7, the day prior the zone's founding, a man drove into a crowd of protesters and shot another man who reached into his car and tried to stop him. The victim was not seriously injured.[84][48]

On June 20 at 2:19 a.m., local residents reported gunshots in the zone to 9-1-1. At least seven shots were fired in under three seconds.[85] After being transported to the hospital by volunteers,[86][87] a 19-year-old man died[12] from multiple gunshot wounds[88] and a 33-year-old man[89] was in critical condition with life-threatening injuries. The shooting occurred at Cal Anderson Park, one block from the empty East Precinct building, abandoned on June 8. SPD attempted to respond but was, according to its blotter, "met by a violent crowd that prevented officers safe access to the victims."[12][84] The New York Times reported that as armed police in riot gear entered the zone, protesters screamed, "The victim left the premises!"[90] City Council member Lisa Herbold, chair of the public safety committee, said the suggestion that the crowd interfered with access to victims "defies belief".[26] A departmental spokeswoman said SPD is reviewing public-source video and body camera video, some of which SPD released,[91][92] but no suspects were in custody. SPD has not determined a motive for the shooting.[84][90] CHOP representatives released a statement saying that the individuals involved may have had history, which seemed to escalate because of "gang affiliations".[93] The Seattle Times reported that the teenager who was killed was an African American[88] and had graduated from high school the previous day.[85] The King County medical examiner's office confirmed the victim's identity as Horace Lorenzo Anderson, who went by his middle name.[88] KIRO-TV reported that he was also a local rapper known as "Lil Mob".[94]

Another shooting occurred on June 21, the second such incident in the zone in less than 48 hours. After being transported in a private vehicle to Harborview Medical Center, a 17-year-old male was treated for a gunshot wound to the arm and released. He declined to speak with SPD detectives.[95][96]

On June 22, Mayor Durkan said the violence was distracting from the message of thousands of peaceful protesters. "We cannot let acts of violence define this movement for change," she said, adding that the city "will not allow for gun violence to continue in the evenings around Capitol Hill." At the same press conference, Police Chief Best spoke of "groups of individuals engaging in shootings, a rape, assault, burglary, arson and property destruction." She added, "I cannot stand by, not another second and watch another black man, or anyone really, die in our streets while people aggressively thwart the efforts of police and other first responders from rescuing them."[97] The mayor announced that officials are working with the community to bring the zone to an end.[95] "It's time for people to go home," she said, "to restore order and eliminate the violence on Capitol Hill."[98]

On June 23, there was a third shooting within a span of four days near the zone, leaving a man in his thirties with wounds that were not life-threatening. SPD was reportedly investigating, but the victim refused to provide information about the attack or describe a suspect.[99] Also on June 23, Seattle's KIRO-TV reported that 33-year-old DeJuan Young, who was critically wounded on June 20, was shot in a separate incident by different people and a block away from where Lorenzo Anderson was mortally wounded. His shooting, said Young, was motivated by racism. "So basically I was shot by, I'm not sure if they're Proud Boys or KKK," said Young from his hospital bed. "But the verbiage that they said was hold this 'N-----' and shot me." He worries that his case is not being properly investigated. "I understand everybody's going to say, 'Oh, it was the CHAZ zone and ya'll asked for the police not to be there, so don't act like ya'll need them now."[100] Technically, however, Young was outside the zone.[101] "I was in Seattle streets," he said. "So what's the excuse now?"[100]

Culture and amenities

Organizers pitched tents next to the former precinct in order to hold the space. They established the No Cop Co-op on June 9, 2020, offering free water, hand sanitizer, snacks donated by the community, and kebabs. Stalls were set up which offered cuisine such as vegan curry while others collected donations for the homeless.[102] Two medical stations were established in the zone — the stations deliver basic health care to the homeless and sex workers.[103] The intersection of 12th and Pine was converted to a square for teach-ins, where a microphone was used to encourage people who were there "to fuck shit up" to go home. An outdoor cinema with a sound system and projector was set up and used to screen open-air movies. The first film shown was 13th, Ava DuVernay's documentary about racism and mass incarceration. The Seattle Department of Transportation provided portable toilets.[6] An area at 11th and Pine was set aside as the "Decolonization Conversation Café", a discussion area with daily topics.[104][105] The Marshall Law Band, a Seattle-based hip-hop fusion group, has performed for protesters.[106][107]

The city still provided services to the area, including waste removal and fire and rescue services; the SPD also stated they responded to 9-1-1 calls within the area.[76] On June 15, KIRO-TV reported a break-in and fire at an auto shop located near the zone, to which the SPD did not respond;[108] Police Chief Best later stated that officers observed the building from a distance and saw no sign of disturbance.[62] The King County public health department provided COVID-19 testing in Cal Anderson Park.[109]

A block-long street mural saying "Black Lives Matter" was painted June 10–11, located on East Pine Street between 10th and 11th Avenues.[110] Individual letters in the mural were uniquely painted by local artists of color, with supplies purchased through donations from demonstrators and passersby.[111] Visitors lit small candles and left flowers at three shrines, which featured photographs and notes expressing sentiments related to George Floyd and other victims of police brutality.[75][112] On June 19, special events ranging from a "grief ritual" to a dance party were held in observation of Juneteenth.[104][113]

Vegetable gardens began to materialize prior to June 11 in Cal Anderson Park, where activists started to grow a variety of food products from seedlings.[114] The gardens were initiated by a single basil plant, introduced by Marcus Henderson, a resident of the Columbia City neighborhood of Seattle.[115][114] Activists expanded the gardens that were "cultivated by and for BIPOC" (those who are black, indigenous, or people of color) and included signage heralding famous black agriculturalists alongside commemorations of victims of police violence.[116]

The Seattle Times on June 11 reported that restaurant owners in the area had an uptick in walk-up business and a concomitant reduction in delivery costs.[117] However, on June 14, USA Today reported that most businesses in the zone had closed, "although a liquor store, ramen restaurant and taco joint are still doing brisk business".[19] Activists live in tents inside the zone;[118] there were more than eighty such tents in the zone on June 19.[119] Outside the zone, urban camping is illegal in Seattle,[120] though even before the zone this law was seldom enforced.[121]

Reactions

Local

Mayor Jenny Durkan called the creation of the zone an attempt to "de-escalate interactions between protesters and law enforcement",[122] while Seattle Police Chief Carmen Best said that her officers would look at different approaches to "reduce [their] footprint" in the Capitol Hill neighborhood.[21] City Council member Kshama Sawant, who belongs to the Trotskyist Socialist Alternative party, spoke to the occupants of Cal Anderson Park on June 8, 2020.[7] She called for the protesters to turn the precinct into a community center for restorative justice.[6][66]

On June 10, Assistant Police Chief Deanna Nollette said in a news conference, "We're trying to get a dialogue going so we can figure out a way to resolve this without unduly impacting the citizens and the businesses that are operating in that area." She said police had received reports that "armed individuals" were running barricades set up by protesters as checkpoints, "intimidat[ing] community members", and that police had "heard anecdotally" of residents and businesses being asked to pay a fee to operate in the area, adding, "This is the crime of extortion."[123] The following day, Best said the police had not received "any formal reports" of extortion, and the Greater Seattle Business Association said they "found no evidence of this occurring".[117] On June 11, the SPD announced their desire to re-enter the abandoned East Precinct building, and said they still operated within the zone's territory.[123][124] Governor Jay Inslee, on the same day, said the zone was "unpermitted" but "largely peaceful".[61] On June 12, Police Chief Best said, "Rapes, robberies and all sorts of violent acts have been occurring in the area and we have not been able to get to it."[125] In the early morning hours of June 12, an unknown man set a fire at the East Precinct building and walked away; community residents extinguished the flames before they could spread beyond the building's external wall or to the nearby tents.[126] Later that day, Mayor Durkan visited the zone and told a New York Times reporter that she did not know of any serious crime that was reported in the area.[127]

On June 16, a deal was struck between CHAZ representatives and the city to "rezone" the occupied area to allow better street access for businesses and local services.[54] On June 17, KING-TV reported that some are frustrated with the occupation of the area near their homes. One couple commented: "What you want from a home is a stress-free environment. You want to be able to sleep well, you want to feel comfortable and we just don't feel comfortable right now." KING-TV reported also receiving anonymous emails from other local residents expressing "real concerns".[128] On June 18, unease was reportedly being expressed by many black protesters about the zone and its use of Black Lives Matter slogans. According to NPR, "Black activists say there must be follow-through to make sure their communities remain the priority in a majority-white protest movement whose camp has taken on the feel of a neighborhood block party that's periodically interrupted by chants of 'Black Lives Matter!'"[56]

On June 22, the Mayor of Seattle and the Chief of Police stated in a press conference that the police would reoccupy the East Precinct "peacefully and in the near future".[26][27] No specific timeline was provided.[129] On June 24, CNN quoted the "de facto CHOP leader," hip-hop artist Raz Simone, as saying "a lot of people are going to leave—a lot of people already left" the zone.[28]

Also on June 24, Mayor Durkan proposed a hiring freeze on the police force and a $20 million cut to the SPD budget, a reduction of roughly 5% for the remainder of 2020 as part of an effort to compensate for a revenue shortfall and unforeseen expenses due to the coronavirus epidemic. During a public-comment period, some community members said that the budget cut should be larger and that SPD funds should be redirected to housing and healthcare-related spending.[130] The same day, a dozen businesses, residents and property owners filed a class-action lawsuit in federal court against the City of Seattle, which they alleged had deprived them of due process by tolerating the zone.[131] Stating that they do not wish "to undermine CHOP participants' message or present a counter-message", the plaintiffs declared that their legal rights were "overrun" by the city's "unprecedented decision to abandon and close off an entire city neighborhood", isolating them from the city's services.[132] The plaintiffs seek compensation for lost business, property damage and deprivation of their property rights, plus restoration of full public access.[131]

National

Donald J. Trump @realDonaldTrump Radical Left Governor @JayInslee and the Mayor of Seattle are being taunted and played at a level that our great Country has never seen before. Take back your city NOW. If you don’t do it, I will. This is not a game. These ugly Anarchists must be stopped IMMEDIATELY. MOVE FAST!

June 11, 2020[133]

On June 9, U.S. Senator Ted Cruz from Texas stated that the zone was "endangering people's lives".[76] The next day, President Donald Trump demanded that Governor Inslee and Mayor Durkan "take back" the zone, saying that if they did not do it, he would do it for them.[134] Inslee condemned Trump's involvement in the situation, telling him to "stay out of Washington state's business".[135] Trump followed up by calling the protesters "domestic terrorists".[4] Durkan told President Trump to "go back to [his] bunker".[67] On June 11, Durkan responded further: "Unfortunately, our president wants to tell a story about domestic terrorists who have a radical agenda and are promoting a conspiracy that fits his law and order initiatives. It's simply not true. Lawfully gathering and expressing first amendment rights, demanding we do better as a society, and providing true equity for communities of color is not terrorism. It's patriotism."[136]

USA Today described the zone as a "protest haven".[75] Conservative pundit Guy Benson mocked the occupation of Capitol Hill as "communist cosplay".[137] National Review contrasted the mainstream media coverage of the zone, which they deemed as sympathetic, to the negative coverage of the 2016 Malheur National Wildlife Refuge occupation.[138]

On June 12, the Fox News website published digitally altered photographs of the area, to include a man armed with an assault rifle from earlier Seattle protests; also added to the photographs were smashed windows from other parts of Seattle. In a separate incident, the Fox News website ran articles about protests in Seattle; however, the accompanying photo of a burning city was actually taken in Saint Paul, Minnesota the previous month.[139] Although the area was mainly peaceful, "Fox's coverage contributed to the appearance of armed unrest", stated The Washington Post. The manipulated and wrongly used images were removed, with Fox News stating that it "regrets these errors".[140] On June 15, Monty Python co-founder John Cleese mocked a Fox News anchorwoman for reading on air a Reddit post indicating purported "signs of rebellion" within the zone, which turned out to be a joke referencing a scene from Monty Python and the Holy Grail.[141]

Protesters in other cities sought to replicate the autonomous zone in their own communities. Protesters in Portland, Oregon and in Asheville, North Carolina tried to create autonomous zones but were stopped by police.[142][143] On June 12, Tennessee Governor Bill Lee condemned attempts to create an autonomous area in Nashville,[144] warning protesters in the state that "Autonomous zones, and violence will not be tolerated."[145] In Philadelphia, a group established an encampment that was compared to the Seattle occupation; however, their primary focus was not autonomy but to protest Philadelphia's anti-homelessness laws.[146][147][148] In what CNN called "an apparent reference to the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) in Seattle," protesters on June 22 spray-painted "BHAZ", standing for Black House Autonomous Zone, on the pillars of St. John's Episcopal Church, which sits across the street from Lafayette Square in Washington, D.C.[149] The next day, President Trump tweeted, "There will never be an 'Autonomous Zone' in Washington, D.C., as long as I'm your President. If they try they will be met with serious force!" Twitter placed a public interest notice on Trump's tweet for violating the company's policy against abusive behavior—"specifically," Twitter explained, "the presence of a threat of harm against an identifiable group."[150]

On June 17, the U.S. House Judiciary Committee acrimoniously debated a major police reform bill that marked Congress's first attempt to address the issue since George Floyd died in police custody. Seattle's Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone, Politico reported, "was a recurring theme throughout the proceedings". Rep. Debbie Lesko (R-Ariz.) offered an amendment to cut off federal police grants to any municipality that allows an autonomous zone. Rep. Pramila Jayapal (D-Wash.), whose district includes CHAZ, blamed Fox News and "right-wing media pundits" for spreading misinformation. The bill was eventually approved by a majority-Democratic vote.[151]

References

- Nadeau, Barbie Latza (June 20, 2020). "Seattle Police Investigate Shooting Inside CHAZ". The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- Sun, Deedee (June 9, 2020). "Armed protesters protect East Precinct police building after officers leave area". KIRO. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- McNichols, Joshua. "CHAZ chews on what to do next". KUOW-FM. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Elfrin, Tim (June 11, 2020). "'This is not a game': Trump threatens to 'take back' Seattle as protesters set up 'autonomous zone'". The Washington Post. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Silva, Daniella; Moschella, Matteo (June 11, 2020). "Seattle protesters set up 'autonomous zone' after police evacuate precinct". NBC News. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Burns, Chase (June 10, 2020). "The Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone Renames, Expands, and Adds Film Programming". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Burns, Chase; Smith, Rich; Keimig, Jasmyne (June 9, 2020). "The Dawn of 'Free Capitol Hill'". The Stranger. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Simon, Dan; Reeve, Elle; Silverman, Hollie (June 15, 2020). "Protesters have occupied part of Seattle's Capitol Hill for a week. Here's what it's like inside". CNN. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- "Seattle-area protests: Live updates on Saturday, June 13". The Seattle Times. June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Weill, Kelly (June 16, 2020). "The Far Right Is Stirring Up Violence at Seattle's Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone". The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Burns, Katelyn (June 16, 2020). "Seattle's newly police-free neighborhood, explained". Vox. Retrieved June 19, 2020.

- "'We need help': Neighbors concerned after deadly shooting in Seattle's CHOP zone". king5.com.

- Savransky, Becca (June 15, 2020). "How CHAZ became CHOP: Seattle's police-free zone explained". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

Known as the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone (CHAZ) at first, several protesters in the area made a push for the name to better reflect its purpose and renamed the roughly six-block area. CHOP, the new acronym, now stands for the Capitol Hill Organized (or Occupied) Protest.

- Dwilson, Stephanie Dube (June 10, 2020). "'You're Now Leaving the USA': Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone Declared in Seattle". Heavy. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Rufo, Christopher F. (June 10, 2020). "Anarchy in Seattle". City Journal. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Thalen, Mikael (June 10, 2020). "Seattle's 'Autonomous Zone' releases list of demands". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Fink, Jenni (June 11, 2020). "List of Demands in Seattle 'Autonomous Zone' Includes Black Doctors for Black Patients, End to Prisons". Newsweek. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- McBride, Jessica (June 12, 2020). "Seattle Autonomous Zone Videos: What It's Like Inside the CHAZ". Heavy.com. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Hughes, Trevor (June 14, 2020). "In Seattle's Capitol Hill autonomous protest zone, some Black leaders express doubt about white allies". USA Today. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- "Seattle will move to dismantle protest zone, mayor says". Star Tribune. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- "Live updates: Protesters establish 'Free Capitol Hill' near East Precinct". MyNorthwest. KIRO-FM. June 9, 2020. Archived from the original on June 9, 2020. Retrieved June 9, 2020.

- Grygiel, Chris (June 12, 2020). "Q&A: What's next for Seattle protesters' 'autonomous zone'?". Associated Press. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Carlton, Jim (June 12, 2020). "Seattle Protesters Negotiate Over Leaving 'Autonomous Zone'". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Seattle shrinks CHOP area with street barriers". The Seattle Times. June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Wallace, Danielle (June 16, 2020). "Seattle reaches deal with 'CHOP' to remove temporary roadblocks, replace with concrete barriers". Fox News. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Graham, Nathalie (June 22, 2020). "City of Seattle Exploits Shootings to Crack Down on CHOP". The Stranger. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Gutman, David; Brodeur, Nicole (June 22, 2020). "Seattle police will return to East Precinct, where CHOP has reigned, Durkan says". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Toropin, Konstantin (June 24, 2020). "Leader of Seattle's 'autonomous zone' says many protesters are leaving". CNN. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- "Slog PM: Jamaal Bowman Declares Victory, WTF Is This "Official" CHOP Twitter Account?". The Stranger. June 24, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Cornwell, Paige (June 24, 2020). "Seattle's CHOP shrinking, but demonstrators remain". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Gutman, David (June 25, 2020). "New Black-led group at CHOP says protesters will decide how long they'll stay". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Del Rosario, Simone (June 25, 2020). "CHOP protesters staying put at Seattle police precinct". KCPQ. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Mutasa, Tammy (June 25, 2020). "Future of 'CHOP' still in the air while neighbors worry about future violence". KOMO-TV. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

The crowds have definitely thinned out in the past 48 hours.

- "Demonstrators resist as crews arrive at Seattle protest zone". Associated Press. June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Cornwell, Paige; Hellmann, Melissa; Long, Katherine; Clarridge, Christine (June 26, 2020). "Mayor Durkan meets with protesters after city thwarted from removing barricades at CHOP". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Burns, Chase; Smith, Rich (June 26, 2020). "Slog PM: COVID-19 Loves American Ignorance, Seattle School Will Be Named After an LGBTQI+ Hero". The Stranger. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- "Protester lies in street to prevent crews from removing CHOP barricades". KOMO-TV. June 26, 2020. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Carlton, Jim (June 27, 2020). "Protesters Won't Leave CHOP in Seattle as Tensions Rise". The Wall Street Journal. Retrieved June 27, 2020.

- Banel, Feliks (June 5, 2020). "Long history of racial and economic unrest in Seattle". MyNorthwest. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Burton, Lynsi (November 29, 2014). "WTO riots in Seattle: 15 years ago". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- "Occupy Seattle protesters clash with police on Capitol Hill". The Seattle Times. November 2, 2011. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- "George Floyd protesters take to downtown Seattle streets; 7 arrested". KCPQ. May 29, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Kamb, Lewis (June 9, 2020). "How ambiguity and a loophole undermined Seattle's ban on tear gas during George Floyd demonstrations". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

Between May 30 and June 4, an average of about 71 WSP troopers assisted Seattle police during demonstrations in the city. … Groups of Washington National Guard soldiers, ranging from 74 soldiers on May 31 to 600 soldiers on June 6 and 7, also have been deployed to Seattle at the request of Seattle's Emergency Operations Center and with the governor's authorization.

- Kamb, Lewis; Beekman, Daniel (June 5, 2020). "Seattle mayor, police chief agree to ban use of tear gas on protesters amid ongoing demonstrations". The Seattle Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Jones, Liz; Raftery, Isolde (June 10, 2020). "This 26-year-old 'died three times' after police hit her with a blast ball". KUOW.

- Beekman, Daniel; Brownstone, Sydney (June 8, 2020). "Seattle council members vow 'inquest' into police budget; some say mayor should consider resigning". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- "Seattle-area protests: Live updates for Sunday, June 7". The Seattle Times. June 7, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Green, Sara Jean (June 10, 2020). "Prosecutors say man who shot protester on Capitol Hill likely provoked the incident". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Jimenez, Esmy; Raftery, Isolde (June 8, 2020). "'They gave us East Precinct.' Seattle Police backs away from the barricade". KUOW. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Kroman, David (June 19, 2020). "Confusion, anger in Seattle Police Dept. after East Precinct exit". Crosscut.com. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Kamb, Lewis (June 24, 2020). "Seattle Mayor Jenny Durkan and police Chief Carmen Best: A pairing under stress, put to the test". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Janavel, AJ (June 9, 2020). Protesters take over streets outside abandoned SPD East Precinct (News report which aired 7:33am local time). KCPQ (Q13). Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Hu, Jane C. (June 16, 2020). "What's Really Going On at Seattle's So-Called Autonomous Zone?". Slate. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

Activists turned police's barriers around and declared that the surrounding area—roughly 5½ city blocks, which includes a public park—would be for the people.

- Smith, Rich. "City and CHOP Residents Agree on New Footprint". SLOG. The Stranger.

- Durkan, Jenny. "City of Seattle Engages with Capitol Hill Organized Protest to make Safety Changes". Office of the Mayor. City Of Seattle.

- Allam, Hannah (June 18, 2020). "'Remember Who We're Fighting For': The Uneasy Existence Of Seattle's Protest Camp". NPR. Retrieved June 18, 2020.

- O'Connor, Rachael (June 12, 2020). "Seattle protesters' takeover of city blocks echoes 'Free Derry' of the Troubles". The Irish Post. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Ruiz, Michael (June 9, 2020). "Seattle protesters declare 'cop free zone' after police leave precinct". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Eustachewich, Lia (June 12, 2020). "Rapper Raz Simone accused of being 'warlord' in Seattle's police-free CHAZ". New York Post. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Wallace, Danielle (June 11, 2020). "Seattle autonomous zone 'leader' denies acting like 'warlord' in 'no cop, co-op'". Fox News. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Darcy, Oliver (June 11, 2020). "Right-wing media says Antifa militants have seized part of Seattle. Local authorities say otherwise". CNN. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Chief says 'no cop-free zone' in Seattle during protests". Associated Press. June 16, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- King, Angela; Shepard, Kim (June 15, 2020). "From CHAZ to CHOP:". www.kuow.org. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Misciagna, Vanessa (June 15, 2020). "Organizers refocus message after Seattle's CHAZ becomes CHOP". king5.com. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Frizzelle, Christopher (June 15, 2020). "Slog AM: CHOP Is CHAZ's New Name, SPD's Budget Grew by $100 Million, Supreme Court Protects LBGTQ Workers". The Stranger. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Vansynghel, Margo; Kroman, David (June 17, 2020). "The future of Capitol Hill's protest zone may lie in Seattle history". Crosscut.com. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Baker, Mike (June 11, 2020). "Free Food, Free Speech and Free of Police: Inside Seattle's 'Autonomous Zone'". The New York Times. Archived from the original on June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Rambaran, Vandana (June 10, 2020). "Seattle protesters storm City Hall, demand mayor resign after driving police out of area, declaring autonomous zone". Fox News. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

The protesters continued to camp out in a self-declared “Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone” (CHAZ)-- a region spanning six blocks and encompassing the precinct

- Smith, Rich; Keimig, Jasmyne (June 10, 2020). "Sawant Marches Through City Hall with Demonstrators Demanding Mayor Durkan's Resignation". The Stranger. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Read, Bridget (June 11, 2020). "What's Going On in CHAZ, the Seattle Autonomous Zone?". The Cut. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Thalen, Mikael (June 9, 2020). "Seattle protesters set up a barricaded 'cop-free zone'". The Daily Dot. Archived from the original on June 10, 2020. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Kelly, Kim (June 14, 2020). "Meet the Gun Club Patrolling Seattle's Leftist Utopia". The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Hightower, Kamaria (May 30, 2020). "Mayor Durkan Issues Emergency Orders Proclaiming Civil Emergency Due to Demonstrations and Banning Use of Weapons Throughout City". Mayor of Seattle. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- "Seattle protesters struggle to determine what's next for 'autonomous zone' as Trump lobs threats". The Washington Post. June 12, 2020.

- Miller, Ryan W. (June 12, 2020). "CHAZ, a 'no Cop Co-op': Here's what Seattle's Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone looks like". USA Today.

- Britschgi, Christian (June 10, 2020). "Seattle Protesters Establish 'Autonomous Zone' Outside Evacuated Police Precinct — Is the Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone a brave experiment in self-government or just flash-in-the-pan activism?". Reason. Retrieved June 10, 2020.

- Scruggs, Gregory (June 16, 2020). "This Seattle protest zone is police-free. So volunteers are stepping up to provide security". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Keimig, Jasmyne (June 16, 2020). "Working the Night Shift at CHOP". The Stranger. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Horcher, Gary (June 16, 2020). ""We're sitting ducks in here": Tenants in protest zone asking SPD to resume response to crimes". KIRO-TV. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Mutasa, Tammy (June 17, 2020). "Tensions in Capitol Hill mount as residents, protesters clash over access, crime". KOMO-TV. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Smith, Rich (June 19, 2020). "CHOP Medic Intervened in a Sexual Assault in Cal Anderson". The Stranger. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Notorious 'Proud Boy' arrested in Oregon after fighting in Seattle's CHOP zone". June 25, 2020. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Connor, Tracy (June 25, 2020). "Proud Boy Jailed After Being Caught on Video in Seattle Protest Zone". The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Carter, Mike (June 20, 2020). "One dead, one in critical condition in early morning shooting at Capitol Hill protest zone known as CHOP". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Gutman, David; Kiley, Brendan; Furfaro, Hannah; Carter, Mike (June 20, 2020). "After early morning shooting in CHOP, occupied area returns to its new normal". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Fearnow, Benjamin. "Police Investigating Shooting Inside Seattle's 'No Cop,' CHAZ Zone". Newsweek.

- Hitt, Tarpley (June 20, 2020). "Fatal Shooting Rocks Seattle's Protest Zone". The Daily Beast. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Furfaro, Hannah (June 22, 2020). "Teen who died in CHOP shooting wanted 'to be loved,' those who knew him recall". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "Surviving CHOP shooting victim still critical; no arrests yet". KOMO-TV. June 21, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- Fernandez, Manny; Baker, Mike (June 20, 2020). "Fatal Shooting Brought Police Into Seattle's 'Autonomous Zone'". The New York Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Public Affairs (June 20, 2020). "Homicide Investigation Inside Protest Area". Seattle Police Department. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Baumann, Lisa (June 20, 2020). "Shooting in Seattle protest zone leaves 1 dead, 1 injured". Associated Press. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Community members outraged and saddened over fatal shooting at the CHOP". KOMO-TV. June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "One dead, another injured in shooting inside CHOP zone". KIRO-TV. June 20, 2020. Retrieved June 21, 2020.

- Johnson, Gene (June 22, 2020). "Seattle to move to dismantle protest zone, mayor says". Associated Press. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Vera, Amir (June 22, 2020). "17-year-old shot in Seattle protest zone". CNN. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Horne, Deborah (June 22, 2020). "'This is about life or death': City says SPD will return to East Precinct". KIRO-TV. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- Stelloh, Tim (June 22, 2020). "Officials tell protesters to leave Seattle's 'autonomous zone'". NBC News. Retrieved June 22, 2020.

- "Police investigate 3rd shooting near Seattle protest zone". Associated Press. June 23, 2020. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Horne, Deborah (June 23, 2020). "Man critically injured in CHOP shooting says he was the victim of a racial attack". KIRO-TV. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Robertson, Sebastian (June 24, 2020). "Man shot near CHOP says protestors saved his life, blasts police response". KING-TV. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Buncombe, Andrew (June 12, 2020). "Seattle's CHAZ: Inside the occupied vegan paradise – and Trump's 'ugly anarchist' hell". The Independent. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Morse, Ian (June 12, 2020). "In Seattle, a 'project' toward a cop-free world". Al Jazeera. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Slog PM: Juneteenth Freedom Marches, Mayor Durkan Meets Mayor Teargas, Yakima Overwhelmed by COVID-19". The Stranger. June 19, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Kiley, Brendan (June 23, 2020). "'I'm still Black and my life still matters.' What is the legacy of CHOP, Seattle's 24/7 protest?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Rietmulder, Michael (June 17, 2020). "Meet CHOP's original house band: Seattle's Marshall Law Band soundtracks a movement". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Keimig, Jasmyne (June 16, 2020). "Flash Bangs and Tear Gas Did Not Stop Marshall Law Band From Playing". The Stranger. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Sun, Deedee (June 15, 2020). ""Nobody showed up": 911 calls bring no response after break in at auto shop near Capitol Hill protest zone". KIRO-TV. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "Coronavirus daily news updates, June 18: What to know today about COVID-19 in the Seattle area, Washington state and the world". The Seattle Times. June 18, 2020. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- "Huge Black Lives Matter mural in progress on Capitol Hill street". KIRO 7 News. June 11, 2020.

- Kamb, Lewis (June 11, 2020). "How the Black Lives Matter street mural came together on Seattle's Capitol Hill". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Hallie, Golden (June 11, 2020). "Seattle protesters take over city blocks to create police-free 'autonomous zone'". The Guardian. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Wafai, Yasmeen (June 19, 2020). "Juneteenth 2020 celebrations in the Seattle area". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 20, 2020.

- Weinberger, Hannah (June 15, 2020). "In Seattle's CHAZ, a community garden takes root | Crosscut". crosscut.com. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Baume, Matt (June 12, 2020). "Meet the Farmer Behind CHAZ's Vegetable Gardens". The Stranger. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Scruggs, Gregory; Kornfield, Meryl (June 20, 2020). "Police enter Seattle cop-free zone after shooting kills a 19-year-old, critically injures a man". Washington Post. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Long, Katherine K. (June 11, 2020). "Live: Seattle-area protest updates: No police reports filed about use of weapons to extort Capitol Hill businesses, Best says". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Read, Richard (June 25, 2020). "Seattle's police-free zone was created in a day. Dismantling it will take much longer". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Royale, Rosette (June 19, 2020). "Seattle's Autonomous Zone Is Not What You've Been Told". Rolling Stone. Penske Media Corporation. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Section 13, Ordinance No. 106615 of March 21, 1977 (PDF). Seattle City Council. (Seattle Municipal Code 18.12.250) "It is unlawful to camp in any park except at places set aside and posted for such purposes by the Superintendent."

- Greenstone, Scott (September 3, 2018). "Why don't police enforce laws against camping in Seattle parks and streets?". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 26, 2020.

- Mazza, Ed (June 11, 2020). "Politicians Tell Trump To Go Back To The Bunker After His Threat To 'Take Back' Seattle". www.msn.com. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Andone, Dakin; Rose, Andy (June 11, 2020). "Seattle police want to return to vacated precinct in what protesters call an 'autonomous zone'". CNN. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Clark, Peter A. (June 11, 2020). "Seattle Protestors Are Occupying 6 City Blocks As An 'Autonomous Zone'. Some Fear a Police Crackdown Is Imminent". Time. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Sabur, Rozina (June 12, 2020). "Trump threatens to retake Seattle from 'domestic terrorists' as police hand district to protesters". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Detectives Need Help Identifying East Precinct Arson Suspect". SPD Blotter. June 12, 2020. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- "Live Updates on George Floyd Protests: Judge Is Assigned to Officers' Murder Trial". The New York Times. June 13, 2020. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Robertson, Sebastian. "Frustrated residents near Seattle's 'CHOP' zone want their neighborhood back". KING-TV.

- Gutman, David; Brodeur, Nicole (June 22, 2020). "Seattle will phase down CHOP at night, police will return to East Precinct, Durkan says". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Savransky, Becca (June 25, 2020). "Durkan proposes 5% budget cut to Seattle police; some protesters, councilmembers say it's not enough". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Johnson, Gene (June 24, 2020). "Businesses sue Seattle over 'occupied' protest zone". Associated Press. Retrieved June 24, 2020.

- Takahama, Elise (June 24, 2020). "Capitol Hill residents and businesses sue city of Seattle for failing to disband CHOP". The Seattle Times. Retrieved June 25, 2020.

- Donald J. Trump [@realDonaldTrump] (June 11, 2020). "Radical Left Governor @JayInslee and the Mayor of Seattle are being taunted and played at a level that our great Country has never seen before. Take back your city NOW. If you don't do it, I will. This is not a game. These ugly Anarchists must be stopped IMMEDIATELY. MOVE FAST!" (Tweet) – via Twitter.

- Watson, Kathryn (June 12, 2020). "Trump threatens to "take back" Seattle's autonomous zone if leaders don't act: "This is not a game"". CBS News. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- Coleman, Justine (June 11, 2020). "Inslee calls on Trump to 'stay out of Washington state's business'". The Hill. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Combos, Lucas (June 11, 2020). "What's Next For The 'Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone' Is Unclear". Patch. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Garcia, Victor (June 11, 2020). "Guy Benson calls out Seattle protesters for 'playing make-believe,' 'Communist cosplay in the streets'". Fox News. Retrieved June 11, 2020.

- Hoonhout, Tobias (June 12, 2020). "NYT and WaPo Fawn Over Seattle Autonomous Zone Anarchists". National Review. Retrieved June 14, 2020.

- Brunner, Jim (June 15, 2020). "Fox News runs digitally altered images in coverage of Seattle's protests, Capitol Hill Autonomous Zone". The Seattle Times.

- Stanley-Becker, Isaac (June 14, 2020). "Fox News removes manipulated images from coverage of Seattle protests". The Washington Post. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- Blest, Paul. "Fox News Has Officially Lost Its Mind Over the Autonomous Zone in Seattle". vice.com. Vice Media LLC. Retrieved June 15, 2020.

- "Portland abandons its own 'autonomous zone' day after establishing it". Washington Examiner. June 11, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- Stephanie Dube Dwilson (June 13, 2020). "Asheville Autonomous Zone Short-Lived, But Protesters May Try Again". Heavy.com. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- "Nashville Autonomous Zone: Protesters Want to Create a Second CHAZ". Heavy.com. June 13, 2020. Retrieved June 13, 2020.

- McFall, Caitlin (June 12, 2020). "Tennessee Gov. Lee says Nashville autonomous zone won't 'be tolerated'". Fox News. Retrieved June 12, 2020.

- "Officials Fear Growing Center City Encampment To Protest Homelessness Poses Health, Safety Threat". June 15, 2020. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Rushing, Ellie (June 12, 2020). "Philadelphians experiencing homelessness build protest encampment on Ben Franklin Parkway: 'We all matter'". Philadelphia Inquirer. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Tanenbaum, Michael (June 16, 2020). "Philly officials address encampment protest on Benjamin Franklin Parkway". www.phillyvoice.com. Retrieved June 17, 2020.

- Cole, Devan; LeBlanc, Paul (June 23, 2020). "Police remove protesters' tents near White House". CNN. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Robertson, Adi (June 23, 2020). "Twitter restricts Trump threat of 'serious force' against protesters". The Verge. Retrieved June 23, 2020.

- Bresnahan, John; Ferris, Sarah (June 17, 2020). "Antifa, Big Tech, and abortion: Republicans bring culture war to police brutality debate". Politico. Retrieved June 17, 2020.