Donkey Kong Country

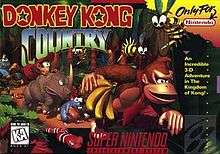

Donkey Kong Country[lower-alpha 1] is a 1994 side-scrolling platform game developed by Rare and published by Nintendo for the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES). It is a reboot of Nintendo's Donkey Kong franchise and follows the gorilla Donkey Kong and his nephew Diddy Kong as they set out to recover their stolen banana hoard from King K. Rool and the Kremlings. The game features 40 levels in which the player collects items, defeats enemies and bosses, and finds secrets on their journey to defeat K. Rool. It also features multiplayer game modes in which two players can work together cooperatively or race against each other.

| Donkey Kong Country | |

|---|---|

North American box art | |

| Developer(s) | Rare |

| Publisher(s) | Nintendo |

| Director(s) |

|

| Designer(s) | Gregg Mayles |

| Programmer(s) | Chris Sutherland |

| Artist(s) |

|

| Writer(s) |

|

| Composer(s) | |

| Series | Donkey Kong |

| Platform(s) | |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Platform |

| Mode(s) | Single-player, multiplayer |

After developing numerous Nintendo Entertainment System games in the 1980s, Rare, a British studio founded by Tim and Chris Stamper, purchased Silicon Graphics workstations to render 3D models. Nintendo, which sought a game to compete with Sega's Aladdin (1993), became interested in Rare's work and purchased a large minority stake in the company. Rare was tasked with reviving the then-dormant Donkey Kong franchise and assembled a team of 12 developers to work on Donkey Kong Country over 18 months. Donkey Kong Country was inspired by the Super Mario series and was one of the first home console games to feature pre-rendered graphics, achieved through a compression technique that allowed Rare to convert 3D models into SNES sprites without losing much detail. It was also the first Donkey Kong game that was neither produced nor directed by franchise creator Shigeru Miyamoto, though he was still involved and contributed design ideas.

Donkey Kong Country was highly anticipated, and Nintendo backed the game with an exceptionally large marketing campaign that cost US$16 million in America alone. It was released in November 1994 to critical acclaim and sold over nine million copies worldwide, making it the third-bestselling SNES game. Critics hailed its visuals as groundbreaking and praised the gameplay for its fluidity and replay value. Donkey Kong Country was the recipient of numerous year-end accolades. Although some retrospective critics have called it overrated, Donkey Kong Country is frequently cited as one of the greatest video games of all time. The game has been ported to a variety of platforms, including the Game Boy product line, the Virtual Console digital distribution service and the Super NES Classic Edition dedicated console.

The success of Donkey Kong Country was a key factor in maintaining the SNES's popularity at a time when players were moving on to technologically superior consoles, such as Sony's PlayStation. It also helped establish Rare as one of the video game industry's leading developers and re-establish Donkey Kong as a cultural icon. Rare developed two sequels for the SNES, Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest (1995) and Donkey Kong Country 3: Dixie Kong's Double Trouble! (1996). After a 14-year hiatus, during which Rare was acquired by Nintendo competitor Microsoft, Retro Studios revived the series with Donkey Kong Country Returns (2010) for the Wii and Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze (2014) for the Wii U.

Gameplay

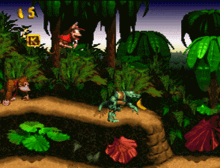

Donkey Kong Country is a side-scrolling platform game in which the player must complete 40 levels[1] to recover the Kongs' banana hoard, which has been stolen by the crocodilian Kremlings. The game features both single-player and multiplayer game modes. In single-player, the player controls one of two characters: the gorilla Donkey Kong or his chimpanzee nephew Diddy Kong, switching between the two as necessary. Donkey is stronger and can defeat enemies more easily, while Diddy is faster and more agile. Both playable Kongs can walk, run, jump, pick up and throw objects, and roll, while Donkey can slap the terrain to defeat enemies or find items.

As the player starts the game, they are placed in a world map that tracks their progress and provides access to levels. Each level on the map is marked with an icon: unfinished levels are marked by Kremlings, while friendly areas are marked by members of the Kong family. Levels consist of varying tasks such as jumping between platforms, swimming, riding in mine carts, launching out of barrel cannons, or swinging from vine to vine. The player must reach the end of the level while avoiding hazards, such as Kremling enemies and bottomless pits. They collect items such as bananas, golden letters that spell out K–O–N–G, extra life balloons, and golden animal tokens that lead to bonus stages. There are also secret paths that lead to bonus games where the player can earn additional lives or other items, as well as gain possible shortcuts through the level.

In certain levels, the player can gain assistance from various animals found by breaking open crates. Animals provide boons such as extra speed or jump height. Each animal can be found in an appropriately themed level: for example, Enguarde, a swordfish that can defeat enemies with its bill, can only be found underwater, while Squawks, a parrot that carries a lantern, is found in one cave level. The player can use the animal for the entirety of the level unless they are hit by an enemy. If the player is hit by an enemy without an animal, the leading Kong runs off, and the player takes control of the other. They will only be able to control that Kong unless they free the other Kong from a barrel. If the player is hit with only one Kong, they lose a life, and if the player loses all lives they receive a game over.

Each section of the map has one boss at the end, which must be defeated to travel back to the main map screen of the whole island. It is possible to access previous world maps without defeating the boss by finding Funky Kong and borrowing his barrel plane. Players use this ability to select the world from the main screen, then the level within it. Other friendly Kongs appear throughout the world map: Cranky Kong provides tips and fourth wall-breaking humour, whilst Candy Kong saves the player's progress. Multiplayer modes include the competitive "Contest" mode or the cooperative "Team" mode.[1] In Contest, each player controls a different set of Kongs and take turns playing each level as quickly as possible; the objective is to complete the most levels in the fastest time. In Team mode, each player takes the role of one of the two Kongs and play as a tag team.

Plot

Donkey Kong Country is a reboot of the Donkey Kong franchise,[2] set long after the events of Donkey Kong (1981) and Donkey Kong Jr. (1982). The original Donkey Kong grows old, moves to Donkey Kong Island, and takes on the moniker Cranky Kong, passing the "Donkey Kong" mantle down to his grandson.[3] One night, the Kremlings, led by King K. Rool, invade Donkey Kong Island and steal the Kongs' hoard of bananas. Donkey, alongside his nephew Diddy, sets out on a journey to reclaim the banana hoard and defeat the Kremlings.[4]

The two Kongs travel throughout Donkey Kong Island, battling the Kremlings and their henchmen, before reaching K. Rool's pirate ship, the Gang-Plank Galleon. The two take on K. Rool and seemingly defeat him, initiating a mock credits roll claiming that the Kremlings developed the game, but K. Rool then gets back up to continue the fight.[5] However, the Kongs persevere, defeat K. Rool, and reclaim the banana hoard.[6]

Development

Background and conception

Prior to Donkey Kong Country, Nintendo's Donkey Kong franchise had been largely dormant since the unsuccessful release of Donkey Kong 3 in 1983. The 1987 Official Nintendo Player's Guide advertised a revival for the Nintendo Entertainment System (NES), The Return of Donkey Kong, that was never released.[7] Aside from occasional cameo appearances in other games and a 1994 remake of the original Donkey Kong for Nintendo's handheld game console, the Game Boy, the Donkey Kong character had not been seen in video games for nearly a decade. Journalist Jeremy Parish, writing for USGamer, described this as "quite an ignominious twist for a character who had once been one of the medium's most recognizable faces".[8]

In 1985, brothers Tim and Chris Stamper, British developers who previously founded the British computer game studio Ultimate Play the Game, established Rare to focus on the burgeoning Japanese video game console market.[9] Nintendo had rebuffed the brothers' efforts for a partnership in 1983, which led Chris Stamper to study the NES hardware for six months.[10] Nintendo had claimed it was impossible to reverse engineer the NES, but Rare managed to do so, prepared several tech demos and showed them to Nintendo executive Minoru Arakawa in Kyoto. Impressed, Nintendo granted Rare an unlimited budget.[11] Rare went on to develop around 60 NES games, which included the Battletoads series and ports of games such as 1982's Marble Madness. Rare's NES output generated enormous profits, but demonstrated little creativity.[11]

When the NES's successor, the Super Nintendo Entertainment System (SNES), was released in 1991, Rare decided to limit its output and, around 1992, invested its NES profit in Silicon Graphics (SGI) workstations to render 3D models.[11][12] Rare took significant financial risks in purchasing the SGI workstations, as they cost £80,000 each.[13] The move made Rare the most technologically advanced developer in the UK and situated it high in the international market.[11] Rare tested the SGI technology with games such as Battletoads Arcade (1994)[12] and began developing a boxing video game, Brute Force, using PowerAnimator. At the time, Nintendo wanted a game to compete with Sega's Aladdin (1993), which featured graphics by Disney animators, so Rare informed Nintendo of its SGI experiments.[14] Nintendo was stunned by Brute Force[14] and bought a 25 per cent stake in the company that gradually increased to 49 per cent—making Rare a second-party developer and leading to the development of Donkey Kong Country.[11] According to character designer Kevin Bayliss, after a meeting, Tim Stamper informed him that Nintendo wanted to revive Donkey Kong for a modern-day audience.[14]

Some sources, including character designer Steve Mayles and head programmer Chris Sutherland, indicate that Donkey Kong Country's development began after Nintendo offered Rare its catalogue of characters to create a game using the SGI technology, and the Stampers chose Donkey Kong.[11][12][13] Conversely, lead designer and Steve Mayles' brother Gregg Mayles recalled that it was Nintendo that requested a Donkey Kong game.[15] Donkey Kong Country was the first Donkey Kong game that was neither directed nor produced by franchise creator Shigeru Miyamoto,[1] who was working on Super Mario World 2: Yoshi's Island (1995) at the time.[16] Despite this, Miyamoto was still involved with the project and provided "certain key pieces of input".[17] Nintendo has a reputation for being proactive to protect its intellectual properties but was relatively uninvolved with Donkey Kong Country, leaving most of the work to Rare.[13][15] Tim Stamper and Gregg Mayles were the only Rare employees who had significant ties to Nintendo during the project.[14]

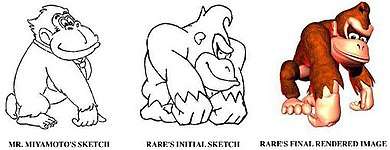

Character design

Bayliss was in charge of redesigning Donkey Kong for Donkey Kong Country, and wanted the new design to be "simplified" and "compact".[14] The character's features were enlarged to make them clearer, while his eyes were taken from Bayliss' Battletoad designs. Steve Mayles also contributed to the design—specifically his mouth, which formed the basis for the other character designs.[14] The red tie was a design choice suggested by Miyamoto in an illustration he faxed Rare,[14][15] as Miyamoto wanted the character to have a distinctive article of clothing like Mario's hat.[18] To develop Donkey Kong's movements, Rare staff spent hours at the nearby Twycross Zoo watching and videotaping gorillas.[13] They found that on the rare occasions when the gorillas moved, their movements were "completely unsuitable for a fast-paced videogame [sic]", and chose to use other animals' movements as a base.[15] Donkey Kong's animations in the final game were loosely based on a horse's gallop.[15] Donkey Kong originally had only three fingers per hand, but Steve Mayles had to add a fourth because Nintendo informed Rare that individuals with three fingers are commonly associated with the yakuza in Japan.[12]

The idea of Donkey Kong having a companion grew out of Rare's intent to have a game mechanic akin to the Super Mario series' power-up system; Gregg Mayles said "we thought a second character could perform this function, look visually impressive and give the player a feeling that they were not alone in the game".[15][18] Gregg Mayles initially intended for the partner to be Donkey Kong Jr. and created Diddy Kong as a redesign of the character.[14][15] However, Nintendo considered the redesign too great a departure from the original one, and asked that Rare either present it as a new character or rework it to match Donkey Kong Jr.'s original appearance.[15] Mayles felt the redesign perfectly suited the updated Donkey Kong universe, so he chose the former.[15] Naming the character was a challenge;[15] Mayles settled on "Dinky Kong" at first, but renamed him Diddy due to a copyright issue with Dinky Toys.[14]

Steve Mayles created the other new Kong characters using the Donkey Kong model as a base.[12] For instance, he created Funky Kong by taking Donkey Kong's model and adding teeth, sunglasses and a bandanna.[19] Gregg Mayles said the team did not put too much thought into creating the characters, simply wanting a diverse cast.[18] The animal companions, such as Rambi the Rhino (who was Rare's "take on a horse"), were an extension of Diddy's function as a power-up.[14][18] A number of animal companions were created but did not appear in the finished product. One, an owl who provided tips, was retooled into Cranky Kong. Cranky, who Rare considered the Donkey Kong character from the arcade games, was intended to be a character who "hark[ened] back to the old times", while his "very dry, sarcastic sense of humour" was influenced by Rare's British background.[14] Cranky's lines were written by Gregg Mayles and Tim Stamper.[18] Rare avoided mentioning that Cranky was the original Donkey Kong in the game and its marketing materials because the team feared that Nintendo would disapprove of the change.[14][20]

As the Donkey Kong franchise did not have much of an established universe, Nintendo gave Rare considerable freedom in expanding its lore.[18] This included having to create new villains.[14] Rare initially considered using the Super Mario character Wario as the main antagonist and developed a storyline in which he stole a time machine from Mario, but Nintendo instructed Rare to create original characters instead.[18] King K. Rool and the Kremlings were originally created for Jonny Blastoff and the Kremling Armada, a cancelled point and click adventure game Rare planned to develop for Macintosh computers. When development of Donkey Kong Country began, Steve Mayles reworked the Kremling designs to fit in the Donkey Kong universe. The Kremlings were originally going to use realistic weapons, such as guns, but Rare decided against this idea because it conflicted with the game's lighthearted tone.[14] Gregg Mayles also wanted K. Rool and the Kremlings to seem somewhat incompetent,[14][18] similar to the cartoon characters Dick Dastardly and Muttley.[18]

Production

Donkey Kong Country was developed over the course of 18 months,[13] with work beginning around August 1993.[12] Rare assembled a team of 12 people to work on the game, and according to product manager Dan Owsen, 20 people worked on Donkey Kong Country throughout the development cycle.[15] [21] The first demo was playable by November 1993.[14] The staff chose to make Donkey Kong Country a side-scrolling platformer because they had grown up playing Nintendo's Super Mario games and wanted to deliver their own "modern" take.[18] At the time, Donkey Kong Country "boast[ed] the most man hours ever invested in a single video game (a total of 22 years shared out across the development team)".[17] In 2019, Gregg Mayles stated that the number of hours the team put into Donkey Kong Country would be impossible in the modern video game industry.[14] He noted that game development was more of a hobby at the time,[14][18] as much of the Rare staff was young and "just felt like we'd been given an opportunity to make something pretty cool, and that's all we were trying to do".[18]

The level design was heavily influenced by that of Super Mario Bros. 3 (1988). Gregg Mayles said: "For me, Super Mario Bros. 3 was the ultimate pinnacle for 2D platform games. We wanted the same kind of structure, but we also wanted it to be extremely flowing – where a skilled player could move effortlessly through the levels at great speed".[15] He wanted to make a game that was "easy to pick up" but was designed to flow seamlessly if a player practiced.[18] As such, objects such as enemies, swinging ropes and barrel cannons were carefully placed so players could continually move through a level as if they were walking up steps. Levels were designed using Post-it Notes that the team pieced together. Gregg Mayles noted that the Post-it Notes kept design "fluid" and made it easy to scrap mistakes.[14] The team began designing levels by establishing a predominant feature (e.g. swinging ropes), before determining the uses of said feature. As Gregg Mayles said, "it was kind of done by getting the framework in place first, and then filling the gaps in later".[14] Secret areas were added while designing levels on Post-it Notes and were inspired by Super Mario and the Indiana Jones films.[18]

The player character's attacks changed considerably during development. Gregg Mayles said that the team wanted moves that would be "iconic".[14] Because he wanted the game to be fast-paced, the attacks needed to suit fast gameplay. Choosing a satisfactory attack proved to be a challenge; Gregg Mayles recalled that the team considered at least six different attacks, such as a slide and a "leapfrog" attack.[14][18] One attack, in which Donkey Kong smashed his fist on an enemy's head to leap, was cut because it interrupted the game's flow. Cutting moves became so common that whenever the team did, Steve Mayles would play the Queen song "Another One Bites the Dust" on a CD.[14] Rare finally settled on the roll, which Gregg Mayles noted worked similarly to a bowling ball. The ability to jump in midair while rolling was implemented because the developers found it was easy to accidentally fall off a ledge during the attack. Gregg Mayles found the change useful, so he incorporated it into the level design.[18]

Donkey Kong Country was one of the first games for a mainstream home video game console to use pre-rendered 3D graphics,[13] a technique used in the earlier 1993 Finnish game Stardust for the Amiga.[21] Rare developed a compression technique that allowed the team to incorporate more detail and animation for each sprite for a given memory footprint than had been previously achieved on the SNES, which better preserves the pre-rendered graphics. Nintendo and Rare called the technique for creating the game's graphics Advanced Computer Modelling (ACM).[15] The ACM process pushed the SNES hardware to its limits and there was concern that it would be impossible to compress the SGI-rendered models, which used millions of colors, into 15-color SNES sprites.[12] A single SGI screen took up more memory than an entire 32 MB SNES cartridge; Gregg Mayles compared it to turning a million-piece jigsaw puzzle into a 1,000 or 100 piece one.[14][18] He described transferring the backgrounds into the game as "the bane of the project"[15] and spent "thousands of hours" trying to split the images into tiles to fit in an SNES cartridge.[18] The team's mentality was to attempt to compress SGI visuals and implement them even if it seemed impossible.[12]

Adapting to the then-cutting-edge SGI workstations was a tense challenge;[13] Steve Mayles said they had "a really steep learning curve".[14] Three programmers handled using the machines with little knowledge of what they could accomplish besides a massive user guide that "wasn't written from an artist point of view".[14] A single model took "ages" to render; the team would often go home at 11PM, and by the next morning the images they were rendering at the time may have completed. The SGI machines required a massive air conditioning unit to prevent overheating, whilst the team worked in the summer heat without relief.[13] A popular rumour suggested that Rare was investigated by the Ministry of Defence for the amount of advanced workstations the studio had; although Gregg Mayles said this was false, Rare did receive complaints regarding the amount of power the SGI hardware used. The Rare farmhouse where the game was developed also frequently lost power, to the puzzlement of the electricity board.[14]

The visuals proved to be a significant focus of development.[12] To showcase the graphical fidelity and immerse the player in the game world, Rare chose not to include a heads-up display, with information—such as the player's banana and life counts—only appearing when relevant.[12][18] The pre-rendered graphics allowed for a more realistic art style, so the team incorporated what would have been simply floating platforms in the Super Mario games into the surrounding environment. For instance, platforms took on the appearance of trees in jungles or walkways in mines to incorporate a sense of believability. Rare also attempted to keep the look of the levels consistent so completely different landscapes would not be right next to each other.[18] Tim Stamper, who maintained constant contact with Nintendo of America and spoke with them every night, encouraged the team "to go to the extremes in terms of visuals"; Steve Mayles recalled that Stamper told the team that he wanted the game to still look good two decades in the future.[12] Programmer Brendan Gunn added that, in addition to Stamper's pushing, the team was also under significant pressure to finish the game in time for Thanksgiving due to Nintendo's competition with Sega.[13]

Simultaneous cooperative gameplay was planned but scrapped due to time and hardware constraints. According to Gregg Mayles, having two players on a single screen was challenging, while split-screen multiplayer was unfeasible. Simultaneous multiplayer also conflicted with his vision of fast gameplay. Mayles has said that if he was to remake Donkey Kong Country, he would want to implement the simultaneous gameplay.[18] Additionally, Donkey Kong was going to wear a hard hat in mine levels, but this feature was replaced by Squawks the Parrot due to the palette limitations imposed by the ACM process, as well as animation difficulties.[12] Sutherland also had to cut down many of K. Rool's animations for the final boss fight so the game could run at a good frame rate, to the chagrin of Steve Mayles.[12] Gunn referred to most of Donkey Kong Country's scrapped concepts as minor, with his "one big regret" being that Donkey Kong walks across "very lazy" dotted lines instead of paths on the world map.[13]

A few weeks into development, Rare, at the point when the team had established how the game would look, presented a demo to Nintendo in Japan. Rare's audience included Miyamoto, Game Boy creator Gunpei Yokoi, and future Nintendo president Genyo Takeda. According to Gregg Mayles, Nintendo was impressed, though Yokoi said that he was concerned the game was "too 3D" to be playable. Mayles attributed this to the "shock" Yokoi felt by seeing such advanced graphics.[14] Upon reviewing the initial product, Nintendo directed Rare to significantly reduce the difficulty because it wanted the game to appeal to a broad audience; Nintendo thought the numerous secrets would provide sufficient challenge to hardcore gamers. At this point, Miyamoto made some last-minute suggestions, such as Donkey Kong's "hand-slap" move, that were incorporated into the final game.[21] In retrospect, Gregg Mayles called Nintendo's input supportive and helpful, as the Rare staff was inexperienced.[18]

Audio

David Wise composed most of Donkey Kong Country's soundtrack.[23] Wise started composing as a freelance musician; he originally assumed his music would be replaced with compositions by Koji Kondo, the Super Mario series' composer, because he understood the importance of the Donkey Kong licence to Nintendo.[22][24] Rare asked Wise to record three jungle demo tunes that were merged to become the "DK Island Swing", the first level's track. Wise said, "I guess someone thought the music was suitable, as they offered me a full time position at Rare".[24] Rare allocated 32 kilobits to Wise.[22] Prior to composing, Wise was shown the graphics and given an opportunity to play the level they would appear in, which gave him a sense of what music he would compose.[12][25] After he figured out what the music would entail, Wise then chose the samples and optimised the music to work on the SNES.[25]

Donkey Kong Country features atmospheric music that mixes natural environmental sounds with prominent melodic and percussive accompaniments.[26] Its 1940s swing music-style soundtrack[27] attempts to evoke the game's environments[26] and includes music from levels set in Africa-inspired jungles, caverns, oceanic reefs, frozen landscapes, and industrial factories.[28] Wise cited Kondo's music for the Super Mario and Legend of Zelda games, Tim and Geoff Follin's music for Plok (1993), synthesizer-based film soundtracks released in the 1980s, early-to-mid-1990s rock and dance music, and his experience with brass instruments as influences.[24][27] Wise wanted to imitate the sound of the Korg Wavestation synthesiser.[26] He originally had "all these wild visions of being able to sample pretty much everything", but could not due to memory restrictions.[22] Wise worked separately from the rest of the team[13] in a former cattle shed,[25] with Tim Stamper occasionally visiting in case he had ideas.[13]

Since Donkey Kong Country featured advanced pre-rendered graphics, Wise wanted to push the limits in terms of audio to create "equally impressive" music and make the most of the small space he was working with.[27][25] He wanted the audio to stand out from other SNES games, just like the visuals.[22] "Aquatic Ambience", the music that plays in the underwater levels, took five weeks to create[25] and was the result of Wise's relentless experimentation to create a "waveform sequence" on the SNES using his Wavestation.[27][25] Wise composed "Aquatic Ambience" after he realized he could use the Wavestation,[22] and considers the track his favorite in the game and its biggest technological accomplishment in regards to the audio.[25] The minimalist "Cave Dweller Concert", which features only a marimba, drums, and synths, was heavily influenced by Stamper, who wanted the track to be abstract and reflect the feeling of uncertainty associated with exploring dark caves.[22][27] Stamper was also the driving force behind incorporating sound effects in the music, as he wanted them to play in levels but was limited by the SNES hardware.[27] The "DK Island Swing" was inspired by jungle and tropical-themed music Wise had been listening to,[22] while K. Rool's theme was heavily influenced by the work of Iron Maiden.[25] The title screen theme, added towards the end of development, is a remix of Nintendo's original Donkey Kong theme and was written to demonstrate how Donkey Kong had evolved since his debut.[25]

Composing Donkey Kong Country helped Wise establish his musical style. Wise noted that when he composed video game music in the 1980s, he was limited by the NES's technological restrictions. When he heard Nintendo's composers create music around the NES's limitations, it encouraged him to go back and refine. Such restrictions helped him understand the importance of a console's sound channels and what would be important to do when composing video game music, so these lessons helped him when he worked on Donkey Kong Country.[14] Wise faced numerous challenges due to the technological restraints of the SNES, such as being unable to directly use a keyboard. As such, Wise composed a "rough" track using the keyboard before transcribing the track in hexadecimal to input in MIDI. Wise had to keep music consistent across the SNES's eight sound channels, noting that if there "was two minutes of music on one of these channels, there had to be exactly two minutes on the other seven channels".[14] Wise noted this was a challenging, time-consuming process.[14] However, it was easier than composing for the NES due to the larger number of sound channels.[13] Wise noted that it likely would have been impossible to create the soundtrack if Rare was developing on the Sega Mega Drive, which had an inferior FM sound chip.[22]

Additionally, Eveline Fischer contributed seven tracks.[23] Fischer was less experienced than Wise, who helped teach her as they worked together. She attempted "to give a feeling of the place you were in [and] a sense of the momentum you needed" through her compositions, which she felt were more atmospheric than Wise's.[27] Funky Kong's theme had originally been written by Robin Beanland for an internal progress video about another Rare game, Killer Instinct (1994). Nintendo decided to use the track in a Donkey Kong Country promotional trailer;[29] Tim Stamper liked the track and wanted to include it in the game itself,[29] so Wise adopted it.[13] Meanwhile, character voice clips were provided by various Rare employees. The chomping noises made by the Klaptrap enemy came from an artist who continually snapped his teeth as he worked, while Mark Betteridge provided the playable Kongs' voice clips and Sutherland voiced the Kremlings.[14] During visits to the Twycross zoo, Wise attempted to record real animal noises for inclusion, but they proved too quiet to be captured by his microphone.[13]

A soundtrack CD, DK Jamz, was released via news media and retailers in November 1994 as a promotional item.[30] A standalone release came in 1995.[31] DK Jamz was one of the earliest video game soundtrack albums that was released in the United States, a practice uncommon at the time.[32]

Release

Nintendo published Donkey Kong Country for the SNES in November 1994. The North American release came first on 21 November, followed by the European release on 24 November and the Japanese release on 26 November.[33] In Japan, the game was released under the title Super Donkey Kong.[34] According to Rare, the game released two weeks ahead of schedule.[17] Donkey Kong Country was released around the same time as Sega's Sonic & Knuckles for the SNES's chief competitor, the Sega Mega Drive. The Los Angeles Times called the coinciding releases a "battle" as both advertised revolutionary technological advances (lock-on technology for Sonic & Knuckles and 3D-rendered graphics for Donkey Kong Country).[35]

Marketing

Nintendo of America chairman Howard Lincoln unveiled Donkey Kong Country at the Consumer Electronics Show in Chicago, which lasted from 23 June to 25 June 1994.[36] The unveiling showcased various gameplay sequences and did not reveal that Donkey Kong Country was an SNES game until the end of the presentation, fooling the audience into believing that it was supposed to be for Nintendo's then-upcoming Nintendo 64. Steve Mayles considered the shock that the audience felt after learning it would release for the SNES the "proudest moment in my game-making career".[14] Donkey Kong Country was backed by an exceptionally large marketing campaign. According to the Los Angeles Times, Nintendo spent US$16 million on Donkey Kong Country marketing in America alone; at the time, significant game releases typically had a much smaller average marketing budget of US$5 million.[35]

Nintendo sent a promotional VHS tape, Donkey Kong Country: Exposed, to subscribers of Nintendo Power magazine.[1][37] Exposed, hosted by comedian Josh Wolf, provides a "behind-the-scenes" glimpse of the Treehouse, the Nintendo of America division where games are tested.[1][37] Nintendo World Report's Justin Berube wrote that Exposed was "probably the first time most people outside of Nintendo learned about the [Treehouse]" and "allowed players to see a game in action at home before it was released... the path to learning about upcoming games was no longer confined to magazines".[37] Exposed also features gameplay tips and interviews.[1][37] It concludes with a segment reminding viewers that the game is available only on the 16-bit SNES, not on rival 32-bit and CD-ROM-based consoles (such as Sega's Mega-CD and 32X) that boasted superior processing power.[37]

In October 1994, Nintendo of America held an online promotional campaign through the internet service CompuServe. The campaign included downloadable video samples of the game, a trivia contest in which 800 people participated, and an hour-long online chat conference attended by 80 people, in which Lincoln, president Minoru Arakawa and vice president of marketing Peter Main answered questions. Nintendo's CompuServe promotion marked an early instance of a major video game company using the internet to promote its products.[38] Nintendo of America also partnered with Kellogg's for a promotional campaign in which the packaging for Kellogg's breakfast cereals featured Donkey Kong Country character art and announced a prize giveaway. The campaign ran from the game's release in November 1994 until April 1995.[39]

David DiRienzo, writing for Hardcore Gaming 101, described Nintendo's Donkey Kong Country promotion as "marketing blitzkrieg": "it was everywhere. You couldn’t escape it. It was on the cover of every magazine. It was on gigantic, imposing displays and marquees at Wal-Mart and Babbages... For kids of the era, November 20th seemed like the eve of a revolution."[40] The emphasis on Donkey Kong Country's SGI-rendered visuals built anticipation for the release.[41] The Exposed VHS tape also contributed significantly to the hype[42] and Nintendo would repeat the strategy with future releases such as Star Fox 64 (1997).[37] Nintendo anticipated to sell approximately two million Donkey Kong Country units in one month; Main acknowledged this was an unprecedented expectation but said "it's based on the off-the-chart reactions we've received from game players and retailers. It's something they haven't seen enough of, in terms of breakthrough components, that advances the state of game-play, visuals and audio".[35]

Rereleases

An alternate, competition-oriented version of Donkey Kong Country was sold through Blockbuster Video. Its changes include a time limit for the playable levels and a scoring system, which had been used in the Nintendo PowerFest '94 and Blockbuster World Video Game Championships II competitions. It was later distributed in limited quantities through Nintendo Power. The competition version of Donkey Kong Country is the rarest licensed SNES game, with only 2,500 cartridges known to exist.[40]

In 2000, Rare developed a port of Donkey Kong Country for Nintendo's Game Boy Color (GBC) handheld console. The port was developed alongside the GBC version of Perfect Dark[43] and many assets, including graphics and audio, were re-used from Rare's Game Boy Donkey Kong games.[40] Aside from graphical and sound-related downgrades due to the GBC's weaker 8-bit hardware, the port is mostly identical to the original release.[44] One level was redesigned while another was added.[40] It also adds bonus modes, including two minigames that supplement the main quest and support multiplayer via the Game Link Cable, as well as Game Boy Printer support.[45][44] Gregg Mayles was not involved with the port but was impressed that it was possible to recreate the entire game on the GBC.[18]

Although Rare was acquired by Nintendo competitor Microsoft in 2002, the studio continued to produce games for Nintendo's Game Boy Advance (GBA) since Microsoft did not have a competing handheld.[11] As such, it developed a version of Donkey Kong Country for the GBA, released in the West in June 2003 and in Japan the following December[46] as part of Nintendo's line of SNES rereleases for the GBA.[47] According to Tim Stamper, the GBA Donkey Kong Country was developed from scratch—using SNES emulators to rip the artwork—because the original materials were stored on floppy disks with outdated file formats.[48] The GBA version adds a new animated introductory cutscene,[49] redesigned user interfaces and world maps,[40] the ability to save progress anywhere, minigames, and a time trial mode.[49] However, it features downgraded graphics and sound.[40][49]

The SNES version of Donkey Kong Country has been digitally rereleased for later Nintendo consoles via the Virtual Console service. It was released for the Wii Virtual Console in Japan and Europe in December 2006, and in North America in February 2007.[50] In September 2012, the game was delisted from the Virtual Console catalogue; the exact reason is unknown, though Kotaku's Jason Schreier noted it may have been related to licensing issues with Rare.[51] Donkey Kong Country returned to the Wii U's Virtual Console in February 2015[52] and was added to the New Nintendo 3DS Virtual Console in March 2016.[53] It was also included in the Super NES Classic Edition, a dedicated console Nintendo released in September 2017.[54]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Donkey Kong Country was very successful upon release in November 1994. Within a month of its launch in the United States, its sales reached nearly 500,000 copies.[78] According to some critics, the game "saved" the SNES, which faced growing competition from more technically proficient consoles like the Sega CD and the PlayStation.[64] At review aggregator GameRankings, the SNES version received an 89% score, the Game Boy Color version 90%, and the Game Boy Advance version 79%.[55][56][57]

The game's novel use of pre-rendered 3D models and visuals were universally lauded among critics, with many citing that its graphics were the first of its kind and helped set it far apart from its contemporaries. Lucas Thomas from IGN and Scott Marriott from AllGame both commended the game's advanced visual techniques and expressed surprise that Nintendo's 16-bit system could deliver such vitality,[64][59] while GameSpot's Frank Provo felt that Donkey Kong Country's graphical prowess rivalled that of the forthcoming 32-bit consoles.[63] Nadia Oxford from USGamer similarly acknowledged that the game's visual allure helped Nintendo save face in a period of uncertainty for cartridge-based games and gave praise to Rare's execution of 3D rendering.[72] Michel Garnier from Jeuxvideo further complimented the game's captivating use of rendering by saying it offered a new depth of unprecedented realism.[67] In retrospect, Nintendo Life's Alex Olney declared that the game's pioneering graphics would survive the test of time,[69] while Oxford was more sceptical, saying that despite the "unholy coupling" of Donkey Kong Country's pre-rendered graphics and the SNES processor, the game featured a variety of "paper thin" backgrounds.[72] Writing for Entertainment Weekly, Bob Strauss labelled the game's backgrounds "movie-like" and praised its "monster" textures and impressive three-dimensional characters, although he mistakenly thought the game was produced from 32-bit technology.[79] Vera Brinkmann from Aktueller Software Markt considered the graphics to be the best she had ever seen on a home console, giving particular praise to Donkey and Diddy Kong's fluid running animations.[73] Jeff Pearson of Nintendojo also appreciated the immersive background mattes and asserted Donkey Kong Country as being a visual masterpiece and best looking game on the SNES,[76] while Alexi Kopalny from Top Secret thought the game's visuals were superior to that of Doom and even likened the graphics to "witchcraft".[77] Shortly before the release of its sequel, Chet McDonnell from Next Generation wrote that Donkey Kong Country featured the best ever graphics on a home console, bolstered by the "superior" colour palette the SNES offered.[68]

Although contemporary critics had praise for the game's fluid and fast-paced platforming, some retrospective reviewers have since taken a more critical stance and described its gameplay as overrated. Thomas felt that Donkey Kong Country's visuals sacrificed gameplay in favour of fast sales and a "short-run attention grab" which did not live up to the standards of some of Miyamoto's more "polished" gameplay designs.[64] Marriott echoed this by criticising the game's lack of originality and Donkey and Diddy Kong's shallow range of attacking moves, while Provo, despite noting acknowledging its addictive appeal, felt it had "straightforward" gameplay.[59][63] McDonnell opined that Donkey Kong Country's gameplay held it back from being a Nintendo blockbuster in its own right.[68] Oxford was one of the retrospective critics who appreciated its fast-flowing gameplay, writing that its levels featured a "surprisingly oppressive" atmosphere which eschewed other platformers' idyllic backdrops.[72] Strauss thought it was wise that Nintendo opted not to emulate the arcade-style gameplay of the original Donkey Kong, while Olney considered the game's new rope swinging and barrel blasting mechanics to be a welcome variation.[79][69] The game's plethora of secrets invited praise among both contemporary and retrospective reviewers: Garnier considered the game's diversity in "animal buddies" and secret collectables to be one of its main strengths, saying that the goal of attaining a 101% completion rate through finding all of the secrets adds a "delightful" replay value.[67] Marriott and Thomas concurred, opining that its hidden bonus levels add a new layer of playability through constantly arousing curiosity in the player.[64][59] Karn Bianco from Cubed3 considered the task of finding the game's wealth of secrets "never too tedious", although he noted its spike in difficulty may instil frustration in some. Donkey Kong Country's boss fights also garnered complaints among critics: Oxford, Olney, Pearson and Bianco all found the bosses lacklustre, uninspiring and repetitive.[69][72][76][74]

Wise's atmospheric soundtrack attracted universal acclaim. Oxford considered the game's soundtrack lends favourably to its "oppressive" vibe and commended Wise's debut to the series, while Marriott felt his rendition offered some of the richest sounds on the SNES.[72][59] Garnier gave particular praise to the soundtrack's diversity, lauding the rhythmic oscillation between levels and distinctive sound effects, in which some add "perfectly" to the game's darker environments.[67] Likewise, Strauss complimented the "CD-quality" music while Kopalny thought that Wise's "captivating" soundtrack asserted itself as a masterpiece in its own right.[79][77] Pearson praised each level's unique musical theme and considered each of them an accurate reflection of their respective environments, while remarking that it pushes the SNES' audio chip to the limit, along with its graphical prowess.[76]

The GBC and GBA iterations were met with general praise. Reviewers commended the fluid and fast-paced gameplay of both versions,[60][66][61] although some considered the Game Boy Advance graphics disappointing. Reviewing the GBA version, Marriott felt that its visuals were "slightly above average" for the handheld console but was not as impressive as those showcased on the SNES,[60] while Eurogamer's Tom Bramwell said that the game appeared slightly "muddier" on the small GBA screen, but nevertheless looked ostensibly the same as the original.[61] Craig Harris of IGN criticised the game's graphical implementation, insisting that the developers could have produced better looking visuals for the system rather than merely "[bumping] up the contrast" of character sprites.[66] Similarly, Ben Kosmina from Nintendo World Report remarked that the GBA's sprites did not live up to the standard of those featured on the SNES.[71] Conversely, the visuals of the Game Boy Color version were more warmly received by critics, considering the console's meagre hardware capabilities. In a positive examination from Nintendo Power, the reviewer felt that the visuals were "still worth going ape over" despite lacking the detail of the original,[70] while Harris lauded Rare's efforts to keep the "CG look" in light of the restrictive graphical limitations.[65]

Awards

The game was awarded GamePro's best graphic achievement award at the 1994 Consumer Electronics Show.[80] It won several awards from Electronic Gaming Monthly, including Best SNES Game, Best Animation, Best Game Duo, and Game of the Year, in their 1994 video game awards.[81] It also received a Nintendo Power Award for Best Overall Game of 1994 and two Kids' Choice awards in 1994 and 1995 for Favorite Video Game.[82] It is the only video game listed in Time's top ten "Best Products" of 1994;[83] this achievement is somewhat overshadowed by the game's later inclusion in Time's 2005 list of Top 10 Most Overrated Games of All Time.[84] The game also rated ninth in GameSpy's 2003 list of the 25 most overrated games of all time.[85] Although described as "overrated" by some critics, the game has appeared on many best video games of all-time lists.[86][87][88][89][90][91] Donkey Kong Country was also ranked as the 90th-best game made for a Nintendo system in Nintendo Power's Top 200 Games list in 2006.[92]

Legacy

Donkey Kong Country's financial success was a major factor in keeping sales of the SNES high at a time when the next generation of consoles, including the Sony PlayStation and the Sega Saturn, were being released. The game sold six million units in its first holiday season.[93] After selling nine million units, Donkey Kong Country became the second-best selling SNES game[28][94] and set a record for the fastest-selling video game of all time.[95] In the United States alone, its Game Boy Advance re-release sold 960,000 copies and earned $26 million by August 2006. Between January 2000 and August 2006, it was the 19th highest-selling game launched for a Nintendo handheld console in the US.[96]

Rare's redesign of the Donkey Kong character has been used in all future Nintendo games featuring him, including his appearances in the Super Smash Bros. series and various Mario spinoff titles.[97] Donkey Kong Country's popularity spawned two direct sequels for SNES; Donkey Kong Country 2: Diddy's Kong Quest was released the following year to critical acclaim and Donkey Kong Country 3: Dixie Kong's Double Trouble! debuted the following year. In addition to starring in Donkey Kong Country 2, the character Diddy Kong was popular enough to feature in his spin-off; Diddy Kong Racing was released for the Nintendo 64 in 1997 to critical acclaim, becoming the console's eighth best-selling game.[28][98] Retro Studios revived the series since Microsoft's acquisition of Rare in 2002, with Donkey Kong Country Returns (2010) releasing for the Wii and Donkey Kong Country: Tropical Freeze (2014) for the Wii U and the Nintendo Switch; both incarnations received critical and commercial success.

Both contemporary and retrospective critics cohesively asserted that Donkey Kong Country's visual appeal helped increase the lifespan of Nintendo's then-fledgling SNES; Matthew Castle from the Official Nintendo Magazine asserted that the game brought next-generation graphics to the console just 12 days before the rival PlayStation's Japanese launch, and proved to consumers that an immediate upgrade was unnecessary.[99] Lucas Thomas from IGN similarly avowed that the game had "saved the SNES" and helped revitalise sales by bringing back many lapsed fans.[64]

In a 1995 interview with Electronic Games magazine, Miyamoto allegedly stated that "Donkey Kong Country proves that players will put up with mediocre gameplay as long as the art is good".[100] However, in 2010 Miyamoto said that "some rumor got out that I didn't really like [Donkey Kong Country]? I just want to clarify that that's not the case, because I was very involved in that. And even emailing almost daily with Tim Stamper right up until the end".[101] Additionally, video game journalist Frank Cifaldi—who owns the Electronic Games issue containing the Miyamoto interview—said that the magazine contains no such quote.[102]

References

Citations

- Langshaw, Mark (18 August 2012). "Retro Corner: 'Donkey Kong Country'". Digital Spy. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Grubb, Jeff (15 March 2013). "Nintendo plans to release Donkey Kong Country Returns 3D on May 24". VentureBeat. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- K., Merritt (21 November 2019). "The Donkey Kong Timeline Is Truly Disturbing". Kotaku. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Rare (1994). "It Was a Dark and Stormy Nite...". Donkey Kong Country Instruction Booklet (PDF). Japan: Nintendo. pp. 4–7. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- Friedman, Daniel (8 January 2019). "Why King K. Rool is dominating Smash fans' attention, and affection". Polygon. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Rare (21 November 1994). Donkey Kong Country (Super Nintendo Entertainment System). Nintendo. Level/area: ending.

Cranky Kong: Well done, Donkey my boy! Who would've known a whipper-snapper like you could've beaten that bunch of no-good Kremlings? You've made an old man proud! Go and look in your hoard, I think you'll be in for a surprise!

- Parish, Jeremy. "10 Interesting Things About Donkey Kong". 1Up.com. Archived from the original on 23 June 2012. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Parish, Jeremy (21 November 2019). "Donkey Kong Country Turns 25: Gaming's Biggest Bluff". USGamer. Retrieved 19 May 2020.

- Hunt, Stuart (December 2010). "A Rare Glimpse". Retro Gamer (84): 28–43. ISSN 1742-3155. OCLC 489477015.

- Dawley, Heidi (29 May 1995). "Killer Instinct for Hire". Bloomberg Businessweek. ISSN 0007-7135. Archived from the original on 2 June 2017. Retrieved 17 July 2017.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McLaughlin, Rus (14 June 2012). "IGN Presents the History of Rare". IGN. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Mayles, Steve; Sutherland, Chris (18 November 2019). DK's Missing Hat & K'Rool's FPS Sacrifice! Talking DKC Tech & Character Design with OG Staff! (25th) (YouTube). GameXplain. Retrieved 8 June 2020.

- McFerran, Damien (27 February 2014). "Month Of Kong: The Making Of Donkey Kong Country". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Mayles, Gregg; Mayles, Steve; Bayliss, Kevin; Sutherland, Chris; Wise, David (21 November 2019). The Donkey Kong Country 25th Anniversary Interview Documentary (YouTube). Shesez. Retrieved 25 May 2020.

- Hunt, Stuart (November 2007). "The Making Of... Donkey Kong Country". The Making Of... Retro Gamer. No. 43. Imagine Publishing. pp. 68–71.

- Sao, Akinori (2017). "Super Mario World & Yoshi's Island Developer Interview". Super NES Classic Edition. Nintendo. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Rarewhere: Donkey Kong Country". Rare. Archived from the original on 28 May 1998. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Mayles, Gregg (16 November 2019). Talking with Rare's Creative Director for DKC's 25th Anniversary! (Cut Content, Wario Plot, & More) (YouTube). GameXplain. Retrieved 7 June 2020.

- Mayles, Steve [@WinkySteve] (11 January 2018). "I only added teeth, bandana and shades to the DK model back in '94, but I still get to claim Funky as mine 😁 He looks much better now, btw" (Tweet). Retrieved 4 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- Zwiezen, Zack (25 November 2019). "Nintendo Was Worried Donkey Kong Country Was 'Too 3D'". Kotaku. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- Nihei 1994.

- Wise, David (20 November 2019). We Got David Wise for DKC's 25th! Favorite Tracks, Tropical Freeze Origins, GBA Ports, & More! (YouTube). GameXplain. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- "Rare: Scribes". Rare. 21 December 2005. Archived from the original on 27 December 2005. Retrieved 13 June 2020.

Let's see. Once he'd polished off the new DKC3 GBA score Dave found the time to dig up a full list, and it looks like this: Robin did Funky's Fugue, Eveline did Simian Segue, Candy's Love Song, Voices of the Temple, Forest Frenzy, Tree Top Rock, Northern Hemispheres and Ice Cave Chant, and the rest was the doing of Mr. Wise. Hot damn! It always makes me feel empowered when we can provide actual, genuine, non-fabricated information.

- Wise 2010.

- Wise, David (5 July 2019). Composer David Wise Dissects Donkey Kong Country's Best Music (YouTube). Game Informer. Retrieved 22 June 2020.

- Wise 2004.

- Wise, David; Novakovic, Eveline; Kirkhope, Grant (31 August 2018). SOUND TEST #06 - Donkey Kong Country (w/David Wise, Eveline Novakovic & Grant Kirkhope) [INTERVIEW] (YouTube). The Sound Test. Retrieved 16 June 2020.

- McFerren 2014.

- Beanland, Robin [@TheRealBeano] (22 February 2019). "Thanks 🙂 Yes it was originally written for an internal update/progress video for KI. @NintendoAmerica liked the track enough to use it for DKC promotion at E3...Tim loved it on the promo video and wanted it on the game. Here's the original version 🙂" (Tweet). Retrieved 13 June 2020 – via Twitter.

- "Get in the Groove with the Music Soundtrack from Donkey Kong and Doom". Press Start. Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 66. Ziff Davis. January 1995. p. 68.

- Kombo (4 May 2012). "Donkey Kong Country, Streets of Rage, New Adventure Island, The Legend of Kage". GameZone. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Elston, Brett (28 April 2009). "17 videogame soundtracks ahead of their time". GamesRadar+. p. 3. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- McFerran, Damien (21 November 2014). "Anniversary: 20 Years Ago Today, Rare Resurrected The Donkey Kong Brand". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Miller, Zachary (30 March 2015). "Donkey Kong Country (Wii U VC) Review Mini". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Kronke, David (15 October 1994). "It's Gonna Be a Video Jungle Out There : Video-game stars Donkey Kong and Sonic the Hedgehog will battle it out with new games backed by tech advances and mega-marketing". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 26 May 2020.

- A. Gillen, Marilyn (9 July 1994). "Sega, Nintendo Bring Big Plans to CES". Billboard. 106 (28): 70. ISSN 0006-2510.

- Berube, Justin (9 September 2014). "Remembering Donkey Kong Country Exposed". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Fitzgerald, Kate (14 November 1994). "Videogames Vie for Online Eyes: Sega, Nintendo, Acclaim Finding Target Audience in Front of Computer Screen". Advertising Age. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.

- "Going Bananas Over Donkey Kong as it's Launched Worldwide". Press Start. Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 66. Ziff Davis. January 1995. p. 66.

- DiRienzo, David (25 January 2015). "Donkey Kong Country". Hardcore Gaming 101. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Oxford, Nadia (23 January 2019). "Super NES Retro Review: Donkey Kong Country". US Gamer. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- "Ultra Hype for the Ultra 64". The Mail. GamePro. No. 79. IDG. February 1996. p. 12.

Remember the videotapes Nintendo mailed out to promote Donkey Kong Country in 1994? The result was an opening-day sales record.

- IGN staff (25 July 2000). "Interrogating Rare's Game Boy Team". IGN. Retrieved 5 June 2020.

- Harris, Craig (22 November 2000). "Donkey Kong Country". IGN. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Provo, Frank (17 May 2006). "Donkey Kong Country Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Kosmina, Ben (5 September 2003). "Donkey Kong Country". Nintendo World Report. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Provo, Frank (11 June 2003). "Donkey Kong Country Review". GameSpot. Retrieved 4 June 2020.

- Cornah, Matt. "Stamped Out! The Donkey Kong Country GBA Trilogy". DK Vine. Retrieved 3 June 2020.

- Harris, Craig (6 June 2003). "Donkey Kong Country". IGN. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- "Donkey Kong Country (SNES / Super Nintendo) Game Profile I News, Reviews, Videos & Screenshots". Nintendo Life. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Schreier, Jason (26 February 2015). "Donkey Kong Country Back On Wii U After Mysterious Two-Year Absence". Kotaku. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Sirani, Jordan (26 February 2015). "Six Donkey Kong Games Arrive on Virtual Console". IGN. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Hillier, Brenna (6 March 2016). "3DS Virtual Console gets SNES classics – Earthbound Donkey Kong Country, more". VG247. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- Soupporis, Aaron (27 September 2017). "SNES Classic Edition review: Worth it for the games alone". Engadget. Retrieved 6 June 2020.

- GameRanking (SNES) n.d.

- GameRanking (GBC) n.d.

- GameRanking (GBA) n.d.

- MetaCritic n.d.

- Marriott (SNES) n.d.

- Marriott (GBA) n.d.

- Bramwell 2003.

- Weekly FT 1995.

- Provo 2007.

- Thomas 2007.

- Harris (GBC) n.d.

- Harris (GBA) n.d.

- Garnier 2010.

- McDonnell 1995.

- Olney 2014.

- Nintendo Power 2000.

- Kosmina 2003.

- Oxford 2017.

- Brinkmann 1995.

- Bianco 2003.

- Strauss, Bob (9 December 1994). "Donkey Kong Country". Entertainment Weekly. No. 252. Meredith Corporation. Retrieved 3 January 2019.

- Pearson 2003.

- Kopalny 1995.

- Staff (20 June 1996). "US RPG Demand Surprises Nintendo". Next Generation. Archived from the original on 6 June 1997. Retrieved 28 July 2019.

- Strauss 1994.

- GamePro 1994a.

- EGM 1994.

- Berube 2014.

- GamePro 1995.

- EGM Staff 2005.

- Turner, Williams & Nutt 2003.

- "Edge Presents: The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". Edge. August 2017.

- "GamesTM Top 100". GamesTM (100). October 2010.

- "The 100 Greatest Video Games of All Time". slantmagazine.com. 9 June 2014. Archived from the original on 12 July 2015.

- Clack, David (January 11, 2010). "FHM's 100 Greatest Games of All Time". FHM. Archived from the original on April 30, 2013. Retrieved October 28, 2017.CS1 maint: BOT: original-url status unknown (link)

- Polygon Staff (27 November 2017). "The 500 Best Video Games of All Time". Polygon.com. Retrieved 1 December 2017.

- "The Top 300 Games of All Time". Game Informer. No. 300. April 2018.

- Nintendo Power 2006.

- Buchanan 2009.

- Kent 2001.

- Next Generation 1996.

- Keiser 2006.

- Hunt 2007.

- "Nintendo 64 Japanese Ranking". Japan Game Charts. 10 April 2008. Archived from the original on 30 December 2008. Retrieved 24 May 2008.

- Castle 2014.

- Kohler 2006.

- Miyamoto 2010.

- Cifaldi, Frank [@frankcifaldi] (27 June 2019). "Sorry, they do talk about tech but there's nothing remotely like that in here" (Tweet). Retrieved 13 June 2020 – via Twitter.

Bibliography

- Berube, Justin (9 September 2014). "Remembering Donkey Kong Country Exposed". Nintendo World Report. NINWR, LLC. Archived from the original on 15 April 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bianco, Karn (9 June 2003). "Donkey Kong Country (Super Nintendo) Review". Cubed3. Archived from the original on 12 February 2018. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Bramwell, Tom (3 June 2003). "Donkey Kong Country". Eurogamer. Brighton: Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Brinkmann, Vera (February 1995). "Affentheater: Donkey Kong Country". Aktueller Software Markt (in German). Berlin: Tronic Verlag (94): 67. Retrieved 7 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Buchanan, Levi (20 March 2009). "Genesis vs. SNES: By the Numbers". IGN.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Castle, Matthew (March 2014). "Rewind: Donkey Kong Country". Official Nintendo Magazine. Bath: Future plc (105): 100–101.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "1UP's 2005 list of the 10 most overrated games". 1UP.com. Ziff Davis. 4 April 2005. Archived from the original on 12 May 2012.

- "Game of the Year". 1995 Video Game Buyer's Guide. Electronic Gaming Monthly. 1994. p. 13.

- "Going Bananas Over Donkey Kong as it's Launched Worldwide". Press Start. Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 66. Ziff Davis. January 1995. p. 66.

- "Get in the Groove with the Music Soundtrack from Donkey Kong and Doom". Press Start. Electronic Gaming Monthly. No. 66. Ziff Davis. January 1995. p. 68.

- Fitzgerald, Kate (14 November 1994). "Videogames Vie for Online Eyes: Sega, Nintendo, Acclaim Finding Target Audience in Front of Computer Screen". Advertising Age. Archived from the original on 9 March 2018.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McDonnell, Chet (January 1995). "Aping Mario? Donkey Kong Country review". Next Generation (1). Imagine Media. p. 102. Retrieved 14 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Garnier, Michel (22 January 2010). "Test du jeu Donkey Kong Country sur SNES". Jeuxvideo.com (in French). Paris: Webedia. Archived from the original on 30 October 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Graphic Achievement". GamePro. No. 62. IDG. September 1994. p. 37.

- "Scary Larry" (December 1994). "Nintendo Went Ape". GamePro. No. 65. IDG. pp. 51–52.

- Nihei, Wes (December 1994). "Gorilla Game Design". Cover Feature. GamePro. No. 65. Newtonville: IDG. pp. 54–55.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "At the Deadline". ProNews. GamePro. No. 68. IDG. March 1995. p. 155.

- "Ultra Hype for the Ultra 64". The Mail. GamePro. No. 79. IDG. February 1996. p. 12.

Remember the videotapes Nintendo mailed out to promote Donkey Kong Country in 1994? The result was an opening-day sales record.

- "Donkey Kong Country for Game Boy Advance". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 6 August 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Donkey Kong Country for Game Boy Color". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 30 October 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- "Donkey Kong Country for Super Nintendo". GameRankings. CBS Interactive Inc. Archived from the original on 24 June 2013. Retrieved 31 August 2013.

- Harris, Craig (22 November 2000). "Donkey Kong Country (GBC review)". IGN.

- Harris, Craig (6 June 2003). "Donkey Kong Country (GBA review)". IGN. Archived from the original on 25 October 2013.

- Hillier, Brenna (4 March 2016). "3DS Virtual Console gets SNES classics – Earthbound Donkey Kong Country, more". VG247.com. Archived from the original on 24 September 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Hunt, Stuart (November 2007). "The Making Of... Donkey Kong Country". The Making Of... Retro Gamer. No. 43. Imagine Publishing. pp. 68–71.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Keiser, Joe (2 August 2006). "The Century's Top 50 Handheld Games". Next Generation. Archived from the original on 10 October 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kent, Steven L. (2001). The Ultimate History of Video Games: From Pong to Pokémon and Beyond—The Story Behind the Craze That Touched Our Lives and Changed the World. Roseville, California: Prima Publishing. pp. 496–497. ISBN 0-7615-3643-4.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kohler, Chris (11 August 2006). "Year of the Monkey: Going ape over Donkey Kong's 25th birthday". 1UP.com. Ziff Davis. Archived from the original on 27 March 2013.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kosmina, Ben (5 September 2003). "Donkey Kong Country Review (GBA) review". Nintendo World Report. Archived from the original on 11 September 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Marriott, Scott Alan. "Donkey Kong Country Review (GBA)". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014.

- Marriott, Scott Alan. "Donkey Kong Country Review (SNES)". AllGame. All Media Network. Archived from the original on 14 November 2014.

- McFerren, Damien (3 December 2013). "Rare: Celebrating 30 years of gaming glory". RedBull.com.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- McFerren, Damien (27 February 2014). "Month Of Kong: The Making Of Donkey Kong Country". NintendoLife. Archived from the original on 22 January 2016.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Donkey Kong Country for Game Boy Advance Reviews". Metacritic. Archived from the original on 27 January 2016.

- Miyamoto, Shigeru (17 June 2010). "E3 2010: Shigeru Miyamoto Likes Donkey Kong Country After All". IGN (Interview).CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Nair, Chandra (February 2014). "A Kong of Ice and Fire". Official Nintendo Magazine. Bath: Future plc (104): 29–35.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "Data stream". News. Next Generation. No. 3. Imagine Media. March 1995. p. 18.

- "1995: The Calm Before the Storm? / April". ng special. Next Generation. No. 13. Imagine Media. January 1996. p. 45.

- Kopalny, A (July 1995). "Donkey Kong Country review". Top Secret (in Polish). Warsaw: Wydawnictwo Bajtek (40): 58. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Oxford, Nadia (25 August 2017). "Super NES Retro Review: Donkey Kong Country". USgamer. Brighton: Gamer Network. Archived from the original on 7 June 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Donkey Kong Country: Exposed (VHS). Redmond, Washington: Nintendo of America. 1994.

- "Super NES Classic Edition". Nintendo of America, Inc. 29 September 2017. Archived from the original on 28 September 2017.

- "Donkey Kong Country". Now Playing. Nintendo Power. No. 139. Nintendo of America Inc. December 2000. p. 156.

- "NP Top 200". Nintendo Power. No. 200. February 2006. pp. 58–66.

- "Industry Recognition - OCRWiki". OverClocked ReMix. Archived from the original on 13 October 2008. Retrieved 26 September 2008.

- Olney, Alex (24 October 2014). "Review: Donkey Kong Country". NintendoLife. Archived from the original on 4 May 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Owsen, Daniel (1994). Donkey Kong Country Instruction Booklet (Booklet). Nintendo. SNS-8X-USA.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Rare (21 November 1994). Donkey Kong Country (SNES). Nintendo. Scene: Credits.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Pearson, Jeff (19 June 2003). "Donkey Kong Country review". Nintendojo. Archived from the original on 5 August 2007. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Provo, Frank (23 February 2007). "Donkey Kong Country Review". GameSpot. New York City: CBS Corporation. Archived from the original on 1 April 2019. Retrieved 4 June 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Schrier, Jason (26 February 2015). "Donkey Kong Country Back On Wii U After Mysterious Two-Year Absence". Kotaku. Archived from the original on 17 April 2015.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Thomas, Lucas M. (20 February 2007). "Donkey Kong Country (SNES review)". IGN. Archived from the original on 23 August 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Turner, Benjamin; Williams, Bryn; Nutt, Christian (19 September 2003). "GameSpy's 2003 list of the 25 most overrated games of all time". GameSpy. Archived from the original on 24 February 2006.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- "おオススメ!! ソフト カタログ!!: スーパードンキーコング". Weekly Famicom Tsūshin. No. 335. May 1995. p. 114.

- Wise, David (December 2004). "The Tepid Seat - Rare Music Team" (Interview). Rare. Archived from the original on 26 January 2007.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Wise, David (December 2010). "Interview with David Wise". Square Enix Music Online (Interview). Interviewed by Chris Greening. Archived from the original on 15 January 2012.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

Further reading

- Waugh, Eric-Jon Rossel (30 August 2006). "A Short History of Rare". Bloomberg Businessweek. Archived from the original on 15 October 2016. Retrieved 17 July 2017.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Donkey Kong Country |

- Official website at the Internet Archive