Domus Aurea

The Domus Aurea (Latin, "Golden House") was a vast landscaped palace built by the Emperor Nero in the heart of ancient Rome after the great fire in 64 AD had destroyed a large part of the city and the aristocratic villas on the Palatine Hill.[1]

| Domus Aurea | |

|---|---|

| Location | Regione III Isis et Serap |

| Built in | c. 64-68 AD |

| Built by/for | Nero Claudius Caesar Augustus Germanicus |

| Type of structure | Roman villa |

| Related | List of ancient monuments in Rome |

Domus Aurea | |

It replaced and extended his Domus Transitoria that he had built as his first palace complex on the site.

Construction

Construction began after the great fire of 64 and was nearly completed before Nero's death in 68, a remarkably short time for such an enormous project.

Nero took great interest in every detail of the project, according to Tacitus,[2] and oversaw the engineer-architects, Celer and Severus, who were also responsible for the attempted navigable canal with which Nero hoped to link Misenum with Lake Avernus.[3][4]

Suetonius claims this of Nero and the Domus Aurea:

When the edifice was finished in this style and he dedicated it, he deigned to say nothing more in the way of approval than that he had at last begun to live like a human being.[5]

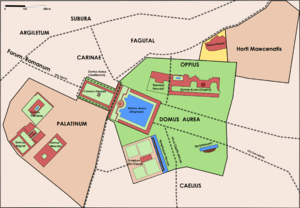

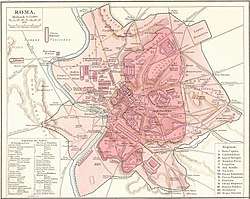

The Domus Aurea complex covered parts of the slopes of the Palatine, Oppian and Caelian hills,[6] with a man-made lake in the marshy valley. Its size can only be approximated, as much of it has not been excavated. Some scholars place it at over 300 acres (1.2 km2),[7] while others estimate its size to have been under 100 acres (0.40 km2).[8] Suetonius describes the complex as "ruinously prodigal" as it included groves of trees, pastures with flocks, vineyards and an artificial lake—rus in urbe, "countryside in the city".[9][10]

Nero also commissioned from the Greek Zenodorus a colossal 35.5 m (120 RF) high bronze statue of himself, the Colossus Neronis.[5][11] Pliny the Elder, however, puts its height at only 30.3 m (106.5 RF).[12] The statue was placed just outside the main palace entrance at the terminus of the Via Appia[5] in a large atrium of porticoes that divided the city from the private villa.[13] This statue may have represented Nero as the sun god Sol, as Pliny saw some resemblance.[14] This idea is widely accepted among scholars[15] but some are convinced that Nero was not identified with Sol while he was alive.[16] The face of the statue was modified shortly after Nero’s death during Vespasian’s reign to make it truly a statue of Sol.[17][16] Hadrian moved it, with the help of the architect Decrianus and 24 elephants,[18] to a position next to the Flavian Amphitheater. This building took the name "Colosseum" in the Middle Ages, after the statue nearby, or, as some historians believe, because of the sheer size of the building.[9]

The Golden House was designed as a place of entertainment, as shown by the presence of 300 rooms without any sleeping quarters.[11] The main palace building was on the Esquiline Hill. No kitchens or latrines have been discovered.[4] Contemporary conveniences such as heating pipes have also not been discovered.[19]

Rooms sheathed in dazzling polished white marble had richly varied floor plans, complete with niches and exedras that concentrated or dispersed the daylight.[20] There were pools in the floors and fountains splashing in the corridors.

Some of the extravagances of the Domus Aurea had repercussions for the future. The architects designed two of the principal dining rooms to flank an octagonal court, surmounted by a dome with a giant central oculus to let in light.[1] It was an early use of Roman concrete construction. One innovation was destined to have an enormous influence on the art of the future: Nero placed mosaics, previously restricted to floors, in the vaulted ceilings. Only fragments have survived,[21] but that technique was to be copied extensively, eventually ending up as a fundamental feature of Christian art: the apse mosaics that decorate so many churches in Rome, Ravenna, Sicily and Constantinople.

Celer and Severus also created an ingenious mechanism, cranked by slaves, that made the ceiling underneath the dome revolve like the heavens, while perfume was sprayed and rose petals were dropped on the assembled diners. According to some accounts, perhaps embellished by Nero's political enemies, on one occasion such quantities of rose petals were dropped that one unlucky guest was asphyxiated (a similar story is told of the emperor Elagabalus).[11]

The extensive gold leaf that gave the villa its name was not the only extravagant element of its decor: stuccoed ceilings were faced with semi-precious stones and ivory veneers, while the walls were frescoed, coordinating the decoration into different themes in each major group of rooms.[22] Pliny the Elder watched it being built and mentions it in his Naturalis Historia.[23]

Frescoes covered every surface that was not more richly finished. The main artist was one Famulus (or Fabulus according to some sources).[24][17] Fresco technique, working on damp plaster, demands a speedy and sure touch: Famulus and assistants from his studio covered a spectacular amount of wall area with frescoes. Pliny, in his Natural History, recounts how Famulus went for only a few hours each day to the Golden House, to work while the light was right. The swiftness of Famulus's execution gives a wonderful unity and astonishing delicacy to his compositions.

Pliny the Elder presents Amulius[25] as one of the principal painters of the domus aurea: "More recently, lived Amulius, a grave and serious personage, but a painter in the florid style. By this artist there was a Minerva, which had the appearance of always looking at the spectators, from whatever point it was viewed. He only painted a few hours each day, and then with the greatest gravity, for he always kept the toga on, even when in the midst of his implements. The Golden Palace of Nero was the prison-house of this artist's productions, and hence it is that there are so few of them to be seen elsewhere."[26]

Legacy

%2C_Domus_aurea%2C_Rome.jpg)

%2C_Domus_aurea%2C_Rome.jpg)

The Domus Aurea was probably never completed.[27]

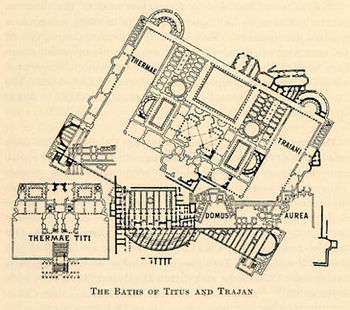

It was a severe embarrassment to Nero's successors as a symbol of decadence and it was stripped of its marble, jewels and ivory within a decade.[11] Soon after Nero’s death, the palace and grounds, encompassing 2.6 km² (c. 1 mi²), were filled with earth and built over: the Baths of Titus were already being built on part of the site, probably the private baths, in 79 AD.[19][17] On the site of the lake, in the middle of the palace grounds, Vespasian built the Flavian Amphitheatre, which could be reflooded at will,[28] with the Colossus Neronis beside it.[1] The Baths of Trajan,[1] and the Temple of Venus and Rome were also built on the site. Within 40 years, the palace was completely obliterated. Paradoxically, this ensured the wall paintings' survival by protecting them from moisture.[29][19][30]

Rediscovery

When a young Roman inadvertently fell through a cleft in the Esquiline hillside at the end of the 15th century, he found himself in a strange cave or grotto filled with painted figures.[11] Soon the young artists of Rome were having themselves let down on boards knotted to ropes to see for themselves.[31] The Fourth Style frescoes that were uncovered then have faded to pale gray stains on the plaster now, but the effect of these freshly rediscovered Grotesque[32] decorations was electrifying in the early Renaissance, which was just arriving in Rome.

When Raphael and Michelangelo crawled underground and were let down shafts to study them, the paintings were a revelation of the true world of antiquity.[33] Beside the graffiti signatures of later tourists, like Casanova and the Marquis de Sade scratched into a fresco inches apart (British Archaeology June 1999),[24] are the autographs of Domenico Ghirlandaio, Martin van Heemskerck, and Filippino Lippi.[34]

It was even claimed that various classical artworks found at this time—such as the Laocoön and his Sons and Venus Kallipygos[35]—were found within or near the Domus's remains, though this is now accepted as unlikely (high quality artworks would have been removed—to the Temple of Peace, for example—before the Domus was covered over with earth).[35]

The frescoes' effect on Renaissance artists was instant and profound (it can be seen most obviously in Raphael's decoration for the loggias in the Vatican), and the white walls, delicate swags, and bands of frieze—framed reserves containing figures or landscapes—have returned at intervals ever since, notably in late 18th century Neoclassicism,[36] making Famulus one of the most influential painters in the history of art.

20th century to present

Discovery led to the arrival of moisture starting the slow, inevitable process of decay; humidity sometimes reaches 90% inside the Domus.[33] Heavy rain was blamed in the collapse of a chunk of ceiling.[37] The presence of trees in the park above the Domus Aurea is likely causing further damage, as tree roots are slowly sinking into the walls, damaging the ceiling and frescoes; chemical compounds released from these roots are provoking additional deterioration.[6][17] Unfortunately, many of these trees cannot be uprooted without damaging the Domus.[38]

The sheer weight of earth on the Domus is causing a problem, as well, and architects believe that the ceiling will eventually collapse if the weight of between 2,500 and 3,000 kilograms per square metre is not lessened.[19] A pilot project is in the works to replace the current park above the Domus, enlarged during Mussolini's regime,[39] with a lighter roof garden planted with the type of flowers described by Pliny, Columella, and other ancient writers.[19]

Today, one of the best-preserved parts of the Domus Aurea is the block of 50 communal toilets which would have been used by slaves and workers in Nero's time.[38]

Increasing concerns about the condition of the building and the safety of visitors resulted in its closing at the end of 2005 for further restoration work.[40] The complex was partially reopened on February 6, 2007, but closed on March 25, 2008 because of safety concerns.[41][33]

The likely remains of Nero's rotating banquet hall and its underlying mechanism were unveiled by archaeologists on September 29, 2009.[42]

Sixty square metres (645 square feet) of the vault of a gallery collapsed on March 30, 2010.[30]

During renovation works on the Palatine Hill at the end of 2018, experts stumbled upon a barrel-vaulted room richly decorated with panthers, centaurs, the god Pan, and a sphinx, believed to have been built between 65 and 68 AD. [43] [44] [45]

See also

- Roman architecture

- List of Roman domes

- List of ancient monuments in Rome

Notes

- Roth

- Annals XV 42

- Warden 1981:272.

- "Emperor Nero's Golden Palace had a room with a rotating ceiling that dropped perfume and rose petals down on its inhabitants - Page 2 of 2". The Vintage News. 2016-09-18. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Suetonius Life of Nero, 31

- Donati, Silvia (2014-06-19). "Rome's Domus Aurea Needs Four-Year Restoration". ITALY Magazine. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Roth: 227

- Warden 1981:271

- M, Dattatreya; al (2016-03-21). "Domus Aurea In Its Full Glory Shown Via Superb 3D Animations". Realm of History. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- McKay, Alexander G., 1924-2007. (1998). Houses, villas, and palaces in the Roman world (Johns Hopkins paperbacks ed.). Baltimore: Johns Hopkins University Press. ISBN 0801859042. OCLC 38079340.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- "The Domus Aurea: Nero's pleasure palace in Rome". www.througheternity.com. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Pliny xxxiv.39

- Boethius 1960:110

- Pliny xxxiv.46

- Claridge 1998: 271

- Boethius 1960:111

- "Golden House of an Emperor - Archaeology Magazine". www.archaeology.org. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Spartianus Hadrian xix

- Rome, Wanted in (2017-07-03). "Domus Aurea: A mad emperor's dream in 3D". Wanted in Rome. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Scaiola, Serena. "Domus Aurea - A Stunning Tour of Emperor Nero's Underground Golden House in Rome - La Gazzetta Italiana". www.lagazzettaitaliana.com. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- http://web.mit.edu/course/21/21h.405/www/DomusAurea/oct.html

- Ball: 21

- Pliny xxxvi.111

- "The buried pleasure palace loved by Michelangelo and Raphael | Art | Agenda". Phaidon. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Given by some sources as Fabullus; Smith (in his Dictionary of Greek and Roman Biography and Mythology) argues that Amulius is the more likely.

- Pliny Chap xxxvii, p.6272

- De la Croix, Horst; Tansey, Richard G.; Kirkpatrick, Diane (1991). Gardner's Art Through the Ages (9th ed.). Thomson/Wadsworth. p. 225. ISBN 0-15-503769-2.

- Br; Specktor, on; May 13, Senior Writer |; ET, 2019 06:42am. "Archaeologists Discovered a Hidden Chamber in Roman Emperor Nero's Underground Palace". Live Science. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "Secret 'Room of the Sphinx' discovered 2,000 years later in Nero's Golden Palace". The Japan Times Online. 2019-05-11. ISSN 0447-5763. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- theintrepidguide (2016-09-23). "Domus Aurea Rome: Visit Rome's Secret Hidden Palace". The Intrepid Guide. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "The Mysterious Hidden Ruins Near the Colosseum | Rome Blog". Roma Experience. 2018-05-22. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Because of their underground origin, these works were referred to as "Grotesques" and their strangeness changed the meaning of the word.

- "Nero's buried golden palace to open to the public - in hard hats". Reuters. 2014-10-24. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Mueller, Tom (April 1997). "Underground Rome". The Atlantic. 279 (4): 48–53. Retrieved 20 January 2011.

- "19th Century Grand Tour Italian Bronze of the 'Callypygian Venus' - LAPADA". lapada.org. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Alex; Turney, ra; Rome, ContributorWriter in (2017-03-18). "The Domus Aurea in Rome: 5 Reasons to Visit Nero's Palace". HuffPost. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Romey (see sources)

- Rome, Wanted in (2019-04-13). "Nero's first palace opens to the public in Rome". Wanted in Rome. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Cox, Cheryl (2016-02-01). "The Underground World of the Domus Aurea :". planet gusto. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "Domus Aurea". World Monuments Fund. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "Rome's Domus Aurea Reopens after Six-Year Restoration". artnet News. 2014-10-27. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- Marta Falconi (AP): Nero's Rotating Hall Unveiled in Rome by Marta Falconi, September 29, 2009, USA Today

- "Sphinx Room at Nero's Domus Aurea re-emerges after 2,000 yrs - English". ANSA.it. 2019-05-08. Retrieved 2019-05-14.

- "Archaeologists discover 2,000-year-old hidden room in Emperor Nero's Golden Palace". The Independent. 2019-05-09. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

- Whelan, Ed. "Enchanting Hidden 'Sphinx' Chamber Discovered At Nero's Golden Palace". www.ancient-origins.net. Retrieved 2019-05-21.

Sources

- Ball, Larry F. (2003). The Domus Aurea and the Roman architectural revolution. Cambridge University Press. ISBN 0-521-82251-3.

- Boethius, Axel (1960). The Golden House of Nero. Ann Arbor: University of Michigan.

- Claridge, Amanda (1998). Rome: An Oxford Archaeological Guide. New York: Oxford University. ISBN 0-19-288003-9.

- Palmer, Alasdair (1999-07-11). "Nero's pleasure dome". London Sunday Times.

- Romey, Kristin M. (July–August 2001). "The Rain in Rome". Archaeology. Archaeological Institute of America. 54 (4): 20. ISSN 0003-8113. Retrieved 2007-02-12.

- Roth, Leland M. (1993). Understanding Architecture: Its Elements, History and Meaning (First ed.). Boulder, CO: Westview Press. pp. 227–8. ISBN 0-06-430158-3.

- Pliny, C. Secundus (c. 77). Natural History.

- Segala, Elisabetta; Ida Sciortino (1999). Domus Aurea. Milan: Electa. ISBN 88-435-7164-8.

- Spartianus, Aelius (117-284). Historia Augusta: The Life of Hadrian.

- Warden, P.G. (1981). "The Domus Aurea Reconsidered". Journal of the Society of Architectural Historians. 40 (4): 271–278. doi:10.2307/989644. JSTOR 989644.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Domus Aurea. |

- Great Buildings on-line: Domus Aurea

- Virtual reconstruction in 3D of the Domus Aurea