Roman Forum

The Roman Forum, also known by its Latin name Forum Romanum (Italian: Foro Romano), is a rectangular forum (plaza) surrounded by the ruins of several important ancient government buildings at the center of the city of Rome. Citizens of the ancient city referred to this space, originally a marketplace, as the Forum Magnum, or simply the Forum.

| |

| Surviving structures | Tabularium, Gemonian stairs, Tarpeian Rock, Temple of Saturn, Temple of Vespasian and Titus, Arch of Septimius Severus, Curia Julia, Rostra, Basilica Aemilia, Forum Main Square, Basilica Iulia, Temple of Caesar, Regia, Temple of Castor and Pollux, Temple of Vesta |

|---|---|

| Imperial comitium | Curia Julia, Rostra Augusti, Umbilicus Urbi, Milliarium Aureum, Lapis Niger, Basilica of Maxentius |

|

| Part of a series on |

| Ancient Rome and the fall of the Republic |

|---|

|

People

Events

Places |

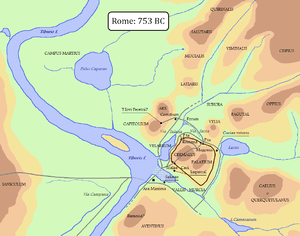

For centuries the Forum was the center of day-to-day life in Rome: the site of triumphal processions and elections; the venue for public speeches, criminal trials, and gladiatorial matches; and the nucleus of commercial affairs. Here statues and monuments commemorated the city's great men. The teeming heart of ancient Rome, it has been called the most celebrated meeting place in the world, and in all history.[1] Located in the small valley between the Palatine and Capitoline Hills, the Forum today is a sprawling ruin of architectural fragments and intermittent archaeological excavations attracting 4.5 million or more sightseers yearly.[2]

Many of the oldest and most important structures of the ancient city were located on or near the Forum. The Roman Kingdom's earliest shrines and temples were located on the southeastern edge. These included the ancient former royal residence, the Regia (8th century BC), and the Temple of Vesta (7th century BC), as well as the surrounding complex of the Vestal Virgins, all of which were rebuilt after the rise of imperial Rome.

Other archaic shrines to the northwest, such as the Umbilicus Urbis and the Vulcanal (Shrine of Vulcan), developed into the Republic's formal Comitium (assembly area). This is where the Senate—as well as Republican government itself—began. The Senate House, government offices, tribunals, temples, memorials and statues gradually cluttered the area.

Over time the archaic Comitium was replaced by the larger adjacent Forum and the focus of judicial activity moved to the new Basilica Aemilia (179 BC). Some 130 years later, Julius Caesar built the Basilica Julia, along with the new Curia Julia, refocusing both the judicial offices and the Senate itself. This new Forum, in what proved to be its final form, then served as a revitalized city square where the people of Rome could gather for commercial, political, judicial and religious pursuits in ever greater numbers.

Eventually much economic and judicial business would transfer away from the Forum Romanum to the larger and more extravagant structures (Trajan's Forum and the Basilica Ulpia) to the north. The reign of Constantine the Great saw the construction of the last major expansion of the Forum complex—the Basilica of Maxentius (312 AD). This returned the political center to the Forum until the fall of the Western Roman Empire almost two centuries later.

Description

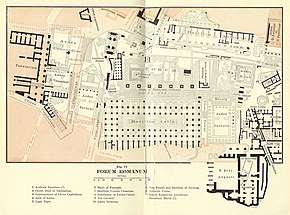

Unlike the later imperial fora in Rome—which were self-consciously modelled on the ancient Greek plateia (πλατεῖα) public plaza or town square—the Roman Forum developed gradually, organically, and piecemeal over many centuries.[3] This is the case despite attempts, with some success, to impose some order there, by Sulla, Julius Caesar, Augustus and others. By the Imperial period, the large public buildings that crowded around the central square had reduced the open area to a rectangle of about 130 by 50 meters.[4]

Its long dimension was oriented northwest to southeast and extended from the foot of the Capitoline Hill to that of the Velian Hill. The Forum's basilicas during the Imperial period—the Basilica Aemilia on the north and the Basilica Julia on the south—defined its long sides and its final form. The Forum proper included this square, the buildings facing it and, sometimes, an additional area (the Forum Adjectum) extending southeast as far as the Arch of Titus.[5]

Originally, the site of the Forum had been a marshy lake where waters from the surrounding hills drained.[6] This was drained by the Tarquins with the Cloaca Maxima.[7] Because of its location, sediments from both the flooding of the Tiber and the erosion of the surrounding hills have been raising the level of the Forum floor for centuries. Excavated sequences of remains of paving show that sediment eroded from the surrounding hills was already raising the level in early Republican times.[8]

As the ground around buildings rose, residents simply paved over the debris that was too much to remove. Its final travertine paving, still visible, dates from the reign of Augustus. Excavations in the 19th century revealed one layer on top of another. The deepest level excavated was 3.60 meters above sea level. Archaeological finds show human activity at that level with the discovery of carbonized wood.

An important function of the Forum, during both Republican and Imperial times, was to serve as the culminating venue for the celebratory military processions known as Triumphs. Victorious generals entered the city by the western Triumphal Gate (Porta Triumphalis) and circumnavigated the Palatine Hill (counterclockwise) before proceeding from the Velian Hill down the Via Sacra and into the Forum.[9]

From here they would mount the Capitoline Rise (Clivus Capitolinus) up to the Temple of Jupiter Optimus Maximus on the summit of the Capitol. Lavish public banquets ensued back down on the Forum.[9] (In addition to the Via Sacra, the Forum was accessed by a number of storied roads and streets, including the Vicus Jugarius, Vicus Tuscus, Argiletum, and Via Nova.)

History

Roman Kingdom

The original, low-lying, grassy wetland of the Forum was drained in the 7th century BC with the building of the Cloaca Maxima, a large covered sewer system that emptied into the Tiber, as more people began to settle between the two hills.

According to tradition, the Forum's beginnings are connected with the alliance between Romulus, the first king of Rome controlling the Palatine Hill, and his rival, Titus Tatius, who occupied the Capitoline Hill. An alliance formed after combat had been halted by the prayers and cries of the Sabine women. Because the valley lay between the two settlements, it was the designated place for the two peoples to meet. Since the early Forum area included pools of stagnant water, the most easily accessible area was the northern part of the valley which was designated as the Comitium. It was here at the Vulcanal that, according to the story, the two parties laid down their weapons and formed an alliance.[10]

The Forum was outside the walls of the original Sabine fortress, which was entered through the Porta Saturni. These walls were mostly destroyed when the two hills were joined.[11] The original Forum functioned as an open-air market abutting on the Comitium, but eventually outgrew its day-to-day shopping and marketplace role. As political speeches, civil trials, and other public affairs began to take up more and more space in the Forum, additional fora throughout the city began to emerge to expand on specific needs of the growing population. Fora for cattle, pork, vegetables and wine specialised in their niche products and the associated deities around them.

Rome's second king, Numa Pompilius (r. 715–673 BC), is said to have begun the cult of Vesta, building its house and temple as well as the Regia as the city's first royal palace. Later Tullus Hostilius (r. 673–642 BC) enclosed the Comitium around the old Etruscan temple where the senate would meet at the site of the Sabine conflict. He is said to have converted that temple into the Curia Hostilia close to where the Senate originally met in an old Etruscan hut. In 600 BC Tarquinius Priscus had the area paved for the first time.

Roman Republic

_(14579302047).jpg)

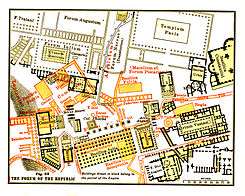

During the Republican period the Comitium continued to be the central location for all judicial and political life in the city.[12] However, in order to create a larger gathering place, the Senate began expanding the open area between the Comitium and the Temple of Vesta by purchasing existing private homes and removing them for public use. Building projects of several consuls repaved and built onto both the Comitium and the adjacent central plaza that was becoming the Forum.[13]

The 5th century BC witnessed the earliest Forum temples with known dates of construction: the Temple of Saturn (497 BC) and the Temple of Castor and Pollux (484 BC).[14] The Temple of Concord was added in the following century, possibly by the soldier and statesman Marcus Furius Camillus. A long-held tradition of speaking from the elevated speakers' Rostra—originally facing north towards the Senate House to the assembled politicians and elites—put the orator's back to the people assembled in the Forum. A tribune known as Caius Licinius (consul in 361 BC) is said to have been the first to turn away from the elite towards the Forum, an act symbolically repeated two centuries later by Gaius Gracchus.[15]

This began the tradition of locus popularis, in which even young nobles were expected to speak to the people from the Rostra. Gracchus was thus credited with (or accused of) disturbing the mos maiorum ("custom of the fathers/ancestors") in ancient Rome. When Censor in 318 BC, Gaius Maenius provided buildings in the Forum neighborhood with balconies, which were called after him maeniana, in order that the spectators might better view the games put on within the temporary wooden arenas set up there.

The Tribune benches were placed on the Forum Romanum, as well. First, they stood next to the senate house; during the late Roman Republic they were placed in front of the Basilica Porcia.

The earliest basilicas (large, aisled halls) were introduced to the Forum in 184 BC by Marcus Porcius Cato, which began the process of "monumentalizing" the site. The Basilica Fulvia was dedicated on the north side of the Forum square in 179 BC. (It was rebuilt and renamed several times, as Basilica Fulvia et Aemilia, Basilica Paulli, Basilica Aemilia). Nine years later, the Basilica Sempronia was dedicated on the south side.[16]

Many of the traditions from the Comitium, such as the popular assemblies, funerals nobles and games, were transferred to the Forum as it developed.[16] Especially notable was the move of the comitia tributa, then the focus of popular politics, in 145 BC. Particularly important and unprecedented political events took place in 133 BC when, in the midst of riots in and around the Forum, the Tribune Tiberius Gracchus was lynched there by a group of Senators.

In the 80s BC, during the dictatorship of Sulla, major work was done on the Forum including the raising of the plaza level by almost a meter and the laying of permanent marble paving stones.[17] (Remarkably, this level of the paving was maintained more or less intact for over a millennium: at least until the sack of Rome by Robert Guiscard and his Normans in 1084, when neglect finally allowed debris to begin to accumulate unabated.)[18]

In 78 BC, the immense Tabularium (Records Hall) was built at the Capitoline Hill end of the Forum by order of the consuls for that year, M. Aemilius Lepidus and Q. Lutatius Catulus. In 63 BC, Cicero delivered his famous speech denouncing the companions of the conspirator Catiline at the Forum (in the Temple of Concord, whose spacious hall was sometimes used as a meeting place by the Senators). After the verdict, they were led to their deaths at the Tullianum, the nearby dungeon which was the only known state prison of the ancient Romans.[19]

Over time, the Comitium was lost to the ever-growing Curia and to Julius Caesar's rearrangements before his assassination in 44 BC.[20] That year, two supremely dramatic events were witnessed by the Forum, perhaps the most famous ever to transpire there: Marc Antony's funeral oration for Caesar (immortalized in Shakespeare's famous play) was delivered from the partially completed speaker's platform known as the New Rostra and the public burning of Caesar's body occurred on a site directly across from the Rostra around which the Temple to the Deified Caesar was subsequently built by his great-nephew Octavius (Augustus).[21] Almost two years later, Marc Antony added to the notoriety of the Rostra by publicly displaying the severed head and right hand of his enemy Cicero there.

Roman Empire

After Julius Caesar's death, and the end of the subsequent Civil Wars, Augustus would finish his great-uncle's work, giving the Forum its final form. This included the southeastern end of the plaza where he constructed the Temple of Divus Iulius and the Arch of Augustus there (both in 29 BC). The Temple of Divius Iulius was placed between Caesar's funeral pyre and the Regia. The Temple's location and reconstruction of adjacent structures resulted in greater organization akin to the Forum of Caesar.[22] The Forum was also witness to the assassination of a Roman Emperor in 69 AD: Galba had set out from the palace to meet rebels but was so feeble that he had to be carried in a litter. He was immediately met by a troop of his rival Otho's cavalry near the Lacus Curtius in the Forum, where he was killed.

During these early Imperial times, much economic and judicial business transferred away from the Forum to larger and more extravagant structures to the north. After the building of Trajan's Forum (110 AD), these activities transferred to the Basilica Ulpia.

The white marble Arch of Septimius Severus was added at the northwest end of the Forum close to the foot of the Capitoline Hill and adjacent to the old, vanishing Comitium. It was dedicated in 203 AD to commemorate the Parthian victories of Emperor Septimius Severus and his two sons against Pescennius Niger, and is one of the most visible landmarks there today. The arch closed the Forum's central area. Besides the Arch of Augustus, which was also constructed following a Roman victory against the Parthians, it is the only triumphal arch in the Forum.[23] The Emperor Diocletian (r. 284–305) was the last of the great builders of Rome's city infrastructure and he did not omit the Forum from his program. By his day it had become highly cluttered with honorific memorials. He refurbished and reorganized it, building anew the Temple of Saturn, Temple of Vesta and the Curia Julis.[24] The latter represents the best-preserved tetrarchic building in Rome. He also reconstructed the rostra at each end of the Forum and added columns.[23]

The reign of Constantine the Great saw the completion of the construction of the Basilica of Maxentius (312 AD), the last significant expansion of the Forum complex.[25] This restored much of the political focus to the Forum until the fall of the Western Roman Empire almost two centuries later.

Medieval

The city's estimated population fell from 750,000–800,000 to 450,000 in 450 AD to 250,000 by 500 AD. The populated areas contracted to the river. Strenuous efforts were made to keep the Forum (and the Palatine structures) intact, not without some success. In the 6th century some of the old edifices within the Forum began to be transformed into Christian churches. On 1 August 608, the Column of Phocas, a Roman monumental column, was erected before the Rostra and dedicated or rededicated in honour of the Eastern Roman Emperor Phocas. This proved to be the last monumental addition made to the Forum. The emperor Constans who visited the city in 665 AD stripped the lead roofs which exposed the monumental buildings to the weather and hastened deterioration. By the 8th century the whole space was surrounded by Christian churches taking the place of the abandoned and ruined temples.[26]

An anonymous 8th-century Einsiedeln Itinerary reports that the Forum was already falling apart at that time. During the Middle Ages, though the memory of the Forum Romanum persisted, its monuments were for the most part buried under debris, and its location was designated the "Campo Vaccino" or "cattle field,"[25] located between the Capitoline Hill and the Colosseum.

After the 8th century the structures of the Forum were dismantled, re-arranged and used to build feudal towers and castles within the local area. In the 13th century these rearranged structures were torn down and the site became a dumping ground. This, along with the debris from the dismantled medieval buildings and ancient structures, helped contribute to the rising ground level.[27]

The return of Pope Urban V from Avignon in 1367 led to an increased interest in ancient monuments, partly for their moral lesson and partly as a quarry for new buildings being undertaken in Rome after a long lapse.

Renaissance

The Forum Romanum suffered some of its worst depredations during the Italian Renaissance, particularly in the decade between 1540 and 1550, when Pope Paul III exploited it intensively for material to build the new Saint Peter's Basilica.[28][29] Just a few years before, in 1536, the Pope had issued an invitation to Holy Roman Emperor Charles V to hold a triumph in Rome on his return from conquering Tunis in North Africa. To prepare the Forum for the procession intended to imitate the pageantry of the ancient Roman triumph, the papal authorities undertook sweeping demolitions of the many medieval structures on the site, to reveal and better display the ancient monuments.[30] This required the clearance of some 200 houses and several churches, the excavation of a new "Via Sacra" to pass under the arches of Titus and Septimius Severus, and the excavation of the more prominent monuments to reveal their foundations.[31]

In 1425 Pope Martin V issued a papal bull inaugurating a campaign of civic improvement and rebuilding in the city, which was depopulated and dominated by ruins.[32] The demand for building materials consequently increased significantly, making the forum a convenient quarry for stone and marble. Since the 12th century, when Rome's civic government was formed, responsibility for protecting the ruins of the forum fell to the maestri di strade under the authority of the Conservatori, Rome's senior magistrates.[33] Historically, the maestri and the Conservatori saw themselves as guardians of Rome's ancient legacy and zealously protected the ruins in the forum from further destruction, but in the 15th century the Papacy gradually encroached upon these prerogatives. The Bull of 1425 strengthened the powers of the maestri in protecting the ruins, but in conferring papal authority the Vatican essentially brought the maestri under its' control and away from the independence of the Conservators.[34]

In the 15th century, the Vatican escalated the issuance of excavation licenses, which gave broad permission to individuals to mine specific sites or structures for stone.[35] In 1452, the ability of the maestri to issue their own excavation licenses was revoked by the Bull of Nicholas V, which absorbed that power into the Vatican. From then on only two authorities in Rome had the power to issue such licenses: the Vatican and the Conservators.[36] This dual, overlapping authority was recognized in 1462 by a Bull of Pius II.[37]

Within the context of these disputes over jurisdiction, ruins in the forum were increasingly exploited and stripped. In 1426, a papal license authorized the destruction of the foundations of a structure called the "Templum Canapare" for burning into lime, provided that half the stone quarried be shared with the Apostolic Camera (the Papal treasury).[38] Between 1431-62 the huge travertine wall between the Senate House and the Forum of Caesar adjoining the Forum Romanum was demolished by grant of Eugenius IV, followed by the demolition of the Templum Sacrae Urbis (1461-2), the Temple of Venus and Rome (1450), and the House of the Vestals (1499), all by papal license.[39] The worst destruction in the forum occurred under Paul III, who in 1540 revoked previous excavation licenses and brought the forum exclusively under the control of the Deputies of the Fabric of the new Saint Peter's Basilica, who exploited the site for stone and marble.[28] Monuments which fell victim to dismantling and the subsequent burning of their materials for lime included the remains of the Arch of Augustus, the Temple of Caesar, parts of the Temple of Antoninus and Faustina, the Temple of Vesta, the steps and foundation of the Temple of Castor and Pollux, and the Regia.[40] The Conservators protested vehemently against the ruination of their heritage, as they perceived it, and on one occasion applied fruitlessly to Pope Gregory XIII (1572-1585) to revoke all licenses for foraging materials, including the one granted to the fabbrica of Saint Peter's in the forum.[41]

Excavation and preservation

.jpg)

The Roman Forum was a site for many artists and architects studying in Rome to sketch during the 17th through the 19th century. The focus of many of these works produced by visiting Northern artists was on current state of the Roman Forum, known locally as the "Campo Vaccino", or "cow field", due to the livestock who grazed on the largely ignored section of the city. Claude Lorrain's 1636 Campo Vaccino shows the extent to which the building in the forum were buried under sediment. From about 1740 to his death in 1772, the artist Giovanni Battista Piranesi worked on a series of 135 etchings depicting 18th-century Rome. Renowned British artist J.M.W. Turner painted Modern Rome – Campo Vaccino in 1839, following his final trip to the city.[42]

The excavation by Carlo Fea, who began clearing the debris from the Arch of Septimius Severus in 1803 marked the beginning of clearing the Forum. Excavations were officially begun in 1898 by the Italian government under the Minister of Public Instruction, Dr. Baccelli.[43] The 1898 restoration had three main objectives: restore fragmented pieces of columns, bases, and cornices to their original locations in the Forum, reach the lowest possible level of the Forum without damaging existing structures, and to identify already half-excavated structures, along with the senate house and Basilica Aemilia. These state-funded excavations were led by Dr. Giacomo Boni until he died in 1925, stopping briefly during World War I.[44]

In 2008 heavy rains caused structural damage to the modern concrete covering holding the "Black Stone" marble together over the Lapis Niger in Rome. Excavations in the forum continue, with new discoveries by archeologists working in the forum since 2009 leading to questions about Rome's exact age. One of these recent discoveries includes a tufa wall near the Lapis Niger used to channel water from nearby aquifers. Around the wall, pottery remains and food scraps allowed archeologists to date the likely construction of the wall to the 8th or 9th century BC, over a century before the traditional date of Rome's founding.[45]

In 2020, Italian archaeologists discovered a sarcophagus and a circular altar dating to the 6th century BC. Experts disagree whether it is a memorial tomb dedicated to Rome's legendary founder, Romulus.[46]

Monuments

The Roman Forum has been a source of inspiration for visual artists for centuries. Especially notable is Giambattista Piranesi who created (1748–76) a set of 135 etchings—the Vedute di Roma (Views of Rome)—in which the Forum figured significantly. (Many of the features documented in Piranesi's views have now vanished.)

Notable artists of the Forum include Maerten van Heemskerck, Pirro Ligorio, Canaletto, Claude Lorrain, Giovanni Paolo Panini, Hubert Robert, J.M.W. Turner and many others.

Temple of Saturn

The Temple of Saturn was one of the more significant buildings located in the Roman Forum. It is believed to have been built in 497 BC and located in Regione VIII Forum Romanum. Little is known about when the Temple was built, as the original temple is believed to have been burnt down by the Gauls early in the fourth century. However it is understood that it was also rebuilt by Munatius Plancus in 42 BC.[47] The eight remaining columns are all that is left of the illustrious temple. Though its exact date of completion is not known, it stands as one of the oldest buildings in the Forum Romanum.[48] The temple originally was to be built to the god Jupiter but was replaced with Saturn; historians are unsure why.[49] The building was not used solely for religious practice; the temple also functioned as a bank for the Roman Society.

The Temple stood in the forum along with four other temples. It stood with the Temple of Concord, Vesta, Castor and Pollox. At each temple, animal sacrifices and rituals were done in front of the religious sites. These acts were meant to provide good fortune to those entering and using the temple.[50] Since the Temple of Saturn also functioned as a bank, and since Saturn was the god of the Golden Age, the sacrifices were made in hope of financial success.[51]

Inside the Temple there were multiple vaults for the public and private ones for individuals. There were also sections of the Temple for public speaking events and feasts which often followed the sacrifices.[52]

Other fora in Rome

Other fora existed in other areas of the city; remains of most of them, sometimes substantial, still exist. The most important of these are a number of large imperial fora forming a complex with the Forum Romanum: the Forum Iulium, Forum Augustum, the Forum Transitorium (also: Forum Nerva), and Trajan's Forum. The planners of the Mussolini era removed most of the Medieval and Baroque strata and built the Via dei Fori Imperiali road between the Imperial Fora and the Forum. There are also:

- The Forum Boarium, dedicated to the commerce of cattle, between the Palatine Hill and the river Tiber,

- The Forum Holitorium, dedicated to the commerce of herbs and vegetables, between the Capitoline Hill and the Servian walls,

- The Forum Piscarium, dedicated to the commerce of fish, between the Capitoline hill and the Tiber, in the area of the current Roman Ghetto,

- The Forum Suarium, dedicated to the commerce of pork, near the barracks of the cohortes urbanae in the northern part of the Campus Martius,

- The Forum Vinarium, dedicated to the commerce of wine, in the area now of the "quartiere" Testaccio, between Aventine Hill and the Tiber.

Other markets were known but remain unidentifiable due to a lack of precise information on each site's function.[53]

See also

- Colossus of Constantine, colossal statue formerly in the west apse of the Basilica of Maxentius

- Farnese Gardens (1550), immediately overlooking the Forum

- Tarpeian Rock, a traditional execution site overlooking the Forum

- Veduta

References

- Grant, Michael (1970), The Roman Forum, London: Weidenfeld & Nicolson; Photos by Werner Forman, p. 11.

- "La Stampa – La top ten dei monumenti più visti Primo il Colosseo, seconda Pompei". Lastampa.it. Retrieved 25 August 2014.

- Watkin, David (2009). The Roman Forum. Harvard University Press, Cambridge, Massachusetts. ISBN 978-0-674-03341-2. Retrieved 6 March 2010., p. 22.

- A more generous estimate, including the surrounding buildings, would be about 200 by 75 meters tall.

- Grant, Op. cit., p. 43.

- Lovell, Isabel (1904). Stories in Stone from the Roman Forum. pp. 8–9.

- Livy. History. p. 1.38.6.

- Ammerman, Albert (1990). "On the Origins of the Forum Romanum". American Journal of Archaeology. 94 (4): 633.

- Grant, Op. cit., p. 16.

- Marucchi, Horace (1906). The Roman Forum and the Palatine According to the Latest Discoveries. Paris: Lefebvre. pp. 1–2.

- Parker, John Henry (1881). The Architectural History of the City of Rome. Oxford: Parker and Company. p. 122.

- Vasaly, Ann (1996). Representations: Images of the World in Ciceronian Oratory. Berkeley: University of California Press. p. 61. ISBN 0-520-07755-5.

- Young, Norwood, ed. (1908). Handbook for Rome and the Campagna. London: John Murray. p. 95.CS1 maint: extra text: authors list (link)

- Richmond, Ian Archibald, et al. (1996), Entry, "Forum Romanum", In: Hornblower, Simon and Antony Spawforth (eds.), The Oxford Classical Dictionary (3rd ed.), Oxford University Press, p. 607.

- Beard, Mary; North, John A.; Price, Simon (1998). Religions of Rome: A History. Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 109 (note 139). ISBN 0-521-30401-6.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Baedeker, Karl (1903). Italy: Handbook for Travellers. Leipzig: Karl Baedeker. p. 251.

- Connolly, Peter and Hazel Dodge (1998), The Ancient City: Life in Classical Athens & Rome, Oxford University Press, pp 109.

- Watkin, Op. cit., p. 106.

- Watkin, Op. cit., p. 79.

- The close relationship between the Comitium and the Forum Romanum eventually faded from the writings of the ancients. The former is last mentioned in the reign of Septimius Severus (c. 200 AD).

- Grant, Op. cit., pp. 111–112.

- "Roman Art and Archaeology," Mark Fullerton, p. 118.

- "Roman Art and Archaeology," Mark Fullerton p. 358

- Connolly, Op. cit., pp. 250–251.

- https://www.history.com/topics/ancient-rome/roman-forum

- Marucchi, Op. cit., p. 9.

- Goodyear, W. H. (1899). Roman and Medieval Art. New York: Macmillan. p. 109.

- Lanciani, 1897; pp. 247-48

- "The Roman Forum". world-archaeology.com. 2010. Retrieved 23 February 2020.

- Mary Beard (2007). The Roman Triumph. Harvard University Press. p. 53.

- David Karmon (2011). The Ruin of the Eternal City. Oxford University Press. p. 107.

- David Karmon (2011). The Ruin of the Eternal City. Oxford University Press. p. 49–50.

- Karmon,2011; p. 54-55

- Karmon,2011; p. 49-50

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1897). The Ruins and excavations of ancient Rome: a companion book for students and travellers. p. 246.

- Karmon,2011; p.65-69

- Karmon,2011; p.69

- Karmon,2011; p.58-60

- Lanciani, 1897; p. 247

- Lanciani, 1897; p=248

- Rodolfo Lanciani (1899). The Destruction of Ancient Rome: A Sketch of the History of the Monuments. Macmillan. pp. 228-31, 234–35.

- "Modern Rome – Campo Vaccino".

- Carter, Jesse Benedict (March 1910). "A Decade of Forum Excavation and the Results for Roman History". The Classical Journal. 5 (5): 202–211. JSTOR 3286845.

- Gray, Mason D. (March 1901). "Recent Excavations in the Roman Forum". The Biblical World. 17 (3): 199–202. doi:10.1086/472777. JSTOR 3136821.

- Pruitt, Sarah. "Forum Excavations Reveal Rome's Advanced Age".

- "Romulus mystery: Experts divided on 'tomb of Rome's founding father'". BBC News. 21 February 2020. Retrieved 28 June 2020.

- Richardson, L. (1 January 1980). "The Approach to the Temple of Saturn in Rome". American Journal of Archaeology. 84 (1): 55. doi:10.2307/504394. JSTOR 504394.

- Richardson, L. (1 January 1980). "The Approach to the Temple of Saturn in Rome". American Journal of Archaeology. 84 (1): 52. doi:10.2307/504394. JSTOR 504394.

- Richardson, L. (1 January 1980). "The Approach to the Temple of Saturn in Rome". American Journal of Archaeology. 84 (1): 51–62. doi:10.2307/504394. JSTOR 504394.

- Watkin, David, and Watkin, David. Wonders of the World Ser. : The Roman Forum. Cumberland, US: Harvard University Press, 2009. ProQuest ebrary.

- Kalas, Gregor (2015). Ashley and Peter Larkin Series in Greek and Roman Culture : Restoration of the Roman Forum in Late Antiquity : Transforming Public Space. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 16.

- Kalas, Gregor (2015). Ashley and Peter Larkin Series in Greek and Roman Culture : Restoration of the Roman Forum in Late Antiquity : Transforming Public Space. Austin: University of Texas Press. p. 17.

- Richardson, L., Jr. (1992). A New Topographical Dictionary of Ancient Rome. JHU Press. ISBN 978-0801843006.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Roman Forum. |

- Reconstruction in 3D of the Roman Forum, Circus Maximus, and the Tiber Island – www.italyrome.info

- Roman Forum's 360x180 degree panorama virtual tour

- Digital Roman Forum, 3D reconstructions of the Roman Forum in c. 400

- Christian Hülsen: The Roman Forum (at LacusCurtius; Hülsen was one of the principal excavators of the Forum)

- Forum Romanum (photo archive)

- Map of the Forum in AD 100, blank or labelled