Dissolution of Austria-Hungary

Dissolution of Austria-Hungary was a major geopolitical event that occurred as a result of the growth of internal social contradictions and the separation of different parts of Austria-Hungary. The reason for the collapse of the state was World War I, the 1918 crop failure and the economic crisis.

On October 17, 1918, the Hungarian Parliament terminated the union with Austria and declared the independence of the country, Czechoslovakia was formed on October 28, followed by the emergence of the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs on October 29. On November 3, the West Ukrainian People's Republic declared independence; on November 6, Poland was re-established in Krakow. Also during the collapse of the empire, the Republic of Tarnobrzeg, the Hutsul Republic, the Lemko Republic, the Komancza Republic, the Republic of Prekmurje, the Hungarian Soviet Republic, the Slovak Soviet Republic, the Banat Republic and the Italian Regency of Carnaro arose.

The remaining territories inhabited by divided peoples fell into the composition of existing or newly formed states. Legally, the collapse of the empire was formalized in the Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye with Austria, which also acted as a peace treaty after the First World War, and in the Treaty of Trianon with Hungary.

Process

On 14 October 1918, Foreign Minister Baron István Burián von Rajecz[1] asked for an armistice based on the Fourteen Points. In an apparent attempt to demonstrate good faith, Emperor Karl issued a proclamation ("Imperial Manifesto of 16 October 1918") two days later which would have significantly altered the structure of the Austrian half of the monarchy. The Polish majority regions of Galicia and Lodomeria were to be granted the option of seceding from the empire, and it was understood that they would join their ethnic brethren in Russia and Germany in resurrecting a Polish state. The rest of Cisleithania was transformed into a federal union composed of four parts—German, Czech, South Slav and Ukrainian. Each of these was to be governed by a national council that would negotiate the future of the empire with Vienna. Trieste was to receive a special status. No such proclamation could be issued in Hungary, where Hungarian aristocrats still believed they could subdue other nationalities and maintain the "Holy Kingdom of St. Stephen".

It was a dead letter. Four days later, on 18 October, United States Secretary of State Robert Lansing replied that the Allies were now committed to the causes of the Czechs, Slovaks and South Slavs. Therefore, Lansing said, autonomy for the nationalities – the tenth of the Fourteen Points – was no longer enough and Washington could not deal on the basis of the Fourteen Points anymore. In fact, a Czechoslovak provisional government had joined the Allies on 14 October. The South Slavs in both halves of the monarchy had already declared in favor of uniting with Serbia in a large South Slav state by way of the 1917 Corfu Declaration signed by members of the Yugoslav Committee. Indeed, the Croatians had begun disregarding orders from Budapest earlier in October.

The Lansing note was, in effect, the death certificate of Austria-Hungary. The national councils had already begun acting more or less as provisional governments of independent countries. With defeat in the war imminent after the Italian offensive in the Battle of Vittorio Veneto on 24 October, Czech politicians peacefully took over command in Prague on 28 October (later declared the birthday of Czechoslovakia) and followed up in other major cities in the next few days. On 30 October, the Slovaks followed in Martin. On 29 October, the Slavs in both portions of what remained of Austria-Hungary proclaimed the State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs. They also declared that their ultimate intention was to unite with Serbia and Montenegro in a large South Slav state. On the same day, the Czechs and Slovaks formally proclaimed the establishment of Czechoslovakia as an independent state.

In Hungary, the most prominent opponent of continued union with Austria, Count Mihály Károlyi, seized power in the Aster Revolution on 31 October. Charles was all but forced to appoint Károlyi as his Hungarian prime minister. One of Károlyi's first acts was to cancel the compromise agreement, officially dissolving the Austro-Hungarian state.

By the end of October, there was nothing left of the Habsburg realm but its majority-German Danubian and Alpine provinces, and Karl's authority was being challenged even there by the German-Austrian state council.[2] Karl's last Austrian prime minister, Heinrich Lammasch, concluded that Karl was in an impossible situation, and persuaded Karl that the best course was to relinquish, at least temporarily, his right to exercise sovereign authority.

Consequences

On 11 November, Karl issued a carefully worded proclamation in which he recognized the Austrian people's right to determine the form of the state.[3] He also renounced the right to participate in Austrian affairs of state. He also dismissed Lammasch and his government from office and released the officials in the Austrian half of the empire from their oath of loyalty to him. Two days later, he issued a similar proclamation for Hungary. However, he did not abdicate, remaining available in the event the people of either state should recall him. For all intents and purposes, this was the end of Habsburg rule.

|

Since my ascent to the throne, I have been constantly trying to lead my people out of the horrors of war, which I am not responsible for. I have not hesitated to restore constitutional life and have opened the way for peoples to develop their own state independently. Still filled with unchangeable love for all My peoples, I do not want to oppose the free development of My Person as an obstacle. I recognize in advance the decision that German Austria will make regarding its future form of government. The people took over the government through their representatives. I waive any share in state affairs. At the same time, I am releasing My Austrian Government from office. May the people of German Austria create and consolidate the reorganization in harmony and forgiveness. The happiness of my peoples has been the goal of my hottest wishes from the beginning. Only inner peace can heal the wounds of this war. |

Seit meiner thronbesteigung war ich unablässig bemüht, Meine Volker aus den Schrecknissen des Krieges herauszuführen, an dessen Ausbruch ich keinerlei Schuld trage. Ich habe nicht gezögert, das verfassungsmaßige Leben wieder herzustellen und haben den Völkern den Weg zu ihrer selbständingen staatlichen Entwicklung eröffnet. Nach wie vor von unwandelbarer Liebe für alle Meine Völker erfüllt, will ich ihrer freien Entfaltung Meine Person nicht als Hindernis entgegenstellen. Im voraus erkenne ich die Entscheidung an, die Deutschösterreich über seine künftige Staatsform trifft. Das Volk hat durch seine Vertreter die Regierung übernommen. Ich verzichte auf jeden Anteil an den Staatsgeschäften. Gleichzeitig enthebe ich Meine österreichische Regierung ihres Amtes. Möge das Volk von Deutschösterreich in Eintracht und Versöhnlichkeit die Neuordnung schaffen und befestigen. Das Glück Meiner Völker war von Anbeginn das Ziel Meiner heißesten Wünsche. Nur der innere Friede kann die Wunden dieses Krieges heilen. |

Karl's refusal to abdicate was ultimately irrelevant. On the day after he announced his withdrawal from Austria's politics, the German-Austrian National Council proclaimed the Republic of German Austria. Károlyi followed suit on 16 November, proclaiming the Hungarian Democratic Republic.

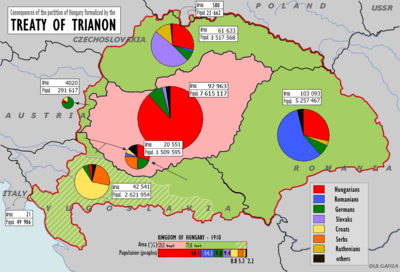

The Treaty of Saint-Germain-en-Laye (between the victors of World War I and Austria) and the Treaty of Trianon (between the victors and Hungary) regulated the new borders of Austria and Hungary, leaving both as small landlocked states. The Allies assumed without question that the minority nationalities wanted to leave Austria and Hungary, and also allowed them to annex significant blocks of German- and Hungarian-speaking territory. As a result, the Republic of Austria lost roughly 60% of the old Austrian Empire's territory. It also had to drop its plans for union with Germany, as it was not allowed to unite with Germany without League approval. The restored Kingdom of Hungary, which had replaced the republican government in 1920, lost roughly 72% of the pre-war territory of the Kingdom of Hungary.

The decisions of the nations of the former Austria-Hungary and of the victors of the Great War, contained in the heavily one-sided treaties, had devastating political and economic effects. The previously rapid economic growth of the Dual Monarchy ground to a halt because the new borders became major economic barriers. All the formerly well-established industries, as well as the infrastructure supporting them, were designed to satisfy the needs of an extensive realm. As a result, the emerging countries were forced to make considerable sacrifices to transform their economies. The treaties created major political unease. As a result of these economic difficulties, extremist movements gained strength; and there was no regional superpower in central Europe.

The new Austrian state was, at least on paper, on shakier ground than Hungary. Unlike its former Hungarian partner, Austria had never been a nation in any real sense. While the Austrian state had existed in one form or another for 700 years, it was united only by loyalty to the Habsburgs. With the loss of 60% of the Austrian Empire's prewar territory, Vienna was now an imperial capital without an empire to support it. However, after a brief period of upheaval and the Allies' foreclosure of union with Germany, Austria established itself as a federal republic. Despite the temporary Anschluss with Nazi Germany, it still survives today. Adolf Hitler cited that all "Germans" – such as him and the others from Austria, etc. – should be united with Germany.

Hungary was severely disrupted by the loss of 72% of its territory, 64% of its population and most of its natural resources. The Hungarian Democratic Republic was short-lived and was temporarily replaced by the communist Hungarian Soviet Republic. Romanian troops ousted Béla Kun and his communist government during the Hungarian–Romanian War of 1919.

In the summer of 1919, a Habsburg, Archduke Joseph August, became regent, but was forced to stand down after only two weeks when it became apparent the Allies would not recognise him.[5] Finally, in March 1920, royal powers were entrusted to a regent, Miklós Horthy, who had been the last commanding admiral of the Austro-Hungarian Navy and had helped organize the counter-revolutionary forces. It was this government that signed the Treaty of Trianon under protest on 4 June 1920 at the Grand Trianon Palace in Versailles, France.[6][7]

In March and again in October 1921, ill-prepared attempts by Karl to regain the throne in Budapest collapsed. The initially wavering Horthy, after receiving threats of intervention from the Allied Powers and neighboring countries, refused his cooperation. Soon afterward, the Hungarian government nullified the Pragmatic Sanction, effectively dethroning the Habsburgs. Two years later, Austria had passed the "Habsburg Law," which not only dethroned the Habsburgs, but banned Karl from ever returning to Austria again.

Subsequently, the British took custody of Karl and removed him and his family to the Portuguese island of Madeira, where he died the following year.

Successor states

The following successor states were formed (entirely or in part) on the territory of the former Austria-Hungary:

- German Austria and the First Austrian Republic

- Hungarian Democratic Republic, Hungarian Soviet Republic, Hungarian Republic and Kingdom of Hungary

- First Czechoslovak Republic ("Czechoslovakia" from 1920 to 1938)

- Second Polish Republic

- State of Slovenes, Croats and Serbs (joined on 1 December 1918 with the Kingdom of Serbia to form the Kingdom of Serbs, Croats and Slovenes, later Kingdom of Yugoslavia)

- West Ukrainian People's Republic (united with the Ukrainian People's Republic through Act Zluky, while its territory was fully overran by the Second Polish Republic)

- Duchy of Bukovina, Transylvania and two-thirds of the Banat were joined to the Kingdom of Romania

Austro-Hungarian lands were also ceded to the Kingdom of Italy. The Principality of Liechtenstein, which had formerly looked to Vienna for protection, formed a customs and defense union with Switzerland, and adopted the Swiss currency instead of the Austrian. In April 1919, Vorarlberg – the westernmost province of Austria – voted by a large majority to join Switzerland; however, both the Swiss and the Allies disregarded this result.

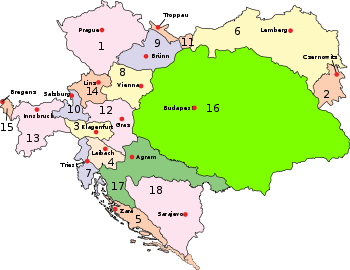

New hand-drawn borders of Austria-Hungary in the Treaty of Trianon and Saint Germain. (1919–1920) |

New borders of Austria-Hungary after the Treaty of Trianon and Saint Germain Border of Austria-Hungary in 1914

Borders in 1914

Borders in 1920

Bosnia and Herzegovina in 1914 |

Post-WWI borders on an ethnic map) |

Territorial legacy

Kingdoms and countries of Austria-Hungary: Cisleithania (Empire of Austria[8]): 1. Bohemia, 2. Bukovina, 3. Carinthia, 4. Carniola, 5. Dalmatia, 6. Galicia, 7. Küstenland, 8. Lower Austria, 9. Moravia, 10. Salzburg, 11. Silesia, 12. Styria, 13. Tyrol, 14. Upper Austria, 15. Vorarlberg; Transleithania (Kingdom of Hungary[8]): 16. Hungary proper 17. Croatia-Slavonia; 18. Bosnia and Herzegovina (Austro-Hungarian condominium) |

The following present-day countries and parts of countries were within the boundaries of Austria-Hungary when the empire was dissolved:

Empire of Austria (Cisleithania):

- Austria (except Burgenland)

- Czech Republic (except the Hlučínsko area)

- Slovenia (except Prekmurje)

- Italy (Trentino, South Tyrol, parts of the province of Belluno and small portions of Friuli-Venezia Giulia)

- Croatia (Dalmatia, Istria)

- Poland (voivodeships of Lesser Poland, Subcarpathia, southernmost part of Silesia (Bielsko and Cieszyn))

- Ukraine (oblasts of Lviv, Ivano-Frankivsk, Ternopil (except its northern corner) and most of the oblast of Chernivtsi)

- Romania (county of Suceava)

- Montenegro (bay of Boka Kotorska, the coast and the immediate hinterland around the cities of Budva, Petrovac and Sutomore)

Kingdom of Hungary (Transleithania):

- Hungary;

- Slovakia

- Austria (Burgenland)

- Slovenia (Prekmurje)

- Croatia (Croatian Baranja and Međimurje county, Fiume as corpus separatum along with Slavonia and Central Croatia were not part of Hungary proper, the latter two were part of the sovereign Kingdom of Croatia-Slavonia)

- Ukraine (oblast of Zakarpattia)

- Romania (region of Transylvania, Partium and parts of Banat, Crișana, and Maramureș)

- Serbia (autonomous province of Vojvodina and northern Belgrade region)

- Poland (Polish parts of Orava and Spiš)

- Bosnia and Herzegovina (the villages of Zavalje, Mali Skočaj and Veliki Skočaj including the immediate surrounding area west of the city of Bihać)

- Montenegro (Sutorina – western part of the Municipality of Herceg Novi between present borders with Croatia (SW) and Bosnia and Herzegovina (NW), Adriatic coast (E) and the township of Igalo (NE))

- Sandžak-Raška region, Austro-Hungarian occupied 1878 until withdrawal in 1908 whilst formally part of the Ottoman Empire

Possessions of the Austro-Hungarian Monarchy

- The empire was unable to gain and maintain large colonies owing to its geographical position. Its only possession outside of Europe was its concession in Tianjin, China, which it was granted in return for supporting the Eight-Nation Alliance in suppressing the Boxer Rebellion. However although the city was only an Austro-Hungarian possession for 16 years, the Austro-Hungarians left their mark on that area of the city, in the form of architecture that still stands in the city.<[9]

Other parts of Europe had been part of the Habsburg monarchy once but had left it before its dissolution in 1918. Prominent examples are the regions of Lombardy and Veneto in Italy, Silesia in Poland, most of Belgium and Serbia, and parts of northern Switzerland and southwestern Germany. They persuaded the government to search out foreign investment to build up infrastructure such as railroads. Despite these measures, Austria-Hungary remained resolutely monarchist and authoritarian.

Literature

- Cornwall, Mark, ed. The Last Years of Austria-Hungary University of Exeter Press, 2002. ISBN 0-85989-563-7

References

- "Hungarian foreign ministers from 1848 to our days". Mfa.gov.hu. Archived from the original on 21 June 2006. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Watson, Ring of Steel pp 542–56

- The 1918 Karl's proclamation. British Library.

- The Karl's I proclamation. British Library.

- "Die amtliche Meldung über den Rücktritt" (in German). Neue Freie Presse, Morgenblatt. 24 August 1919. p. 2. Archived from the original on 26 December 2015. Retrieved 2 June 2017.

- "Trianon, Treaty of". The Columbia Encyclopedia. 2012. Archived from the original on 28 December 2008. Retrieved 28 August 2016.

- Tucker, Spencer; Priscilla Mary Roberts (2005). Encyclopedia of World War I (1 ed.). ABC-CLIO. p. 1183. ISBN 9781851094202.

Virtually the entire population of what remained of Hungary regarded the Treaty of Trianon as manifestly unfair, and agitation for revision began immediately.

- Headlam, James Wycliffe (1911). . In Chisholm, Hugh (ed.). Encyclopædia Britannica. 3 (11th ed.). Cambridge University Press. pp. 2–39.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- For more information about the Austro-Hungarian concession, see: Concessions in Tianjin#Austro-Hungarian concession (1901–1917).