Dean Mahomed

Sheikh Din Muhammad (Bengali: শেখ দীন মোহাম্মদ; 1759–1851) was an Indian traveller, surgeon and entrepreneur who was one of the most notable early non-European immigrants to the Western World.[1] Due to his foreign origin, his name is often spelled various ways in English documentation. He introduced Indian cuisine and shampoo baths to Europe, where he offered therapeutic massage.[lower-alpha 1] He was also the first Indian to publish a book in English.[2][3]

Sake Dean Mahomed | |

|---|---|

শেখ দীন মোহাম্মদ شیخ دین محمد | |

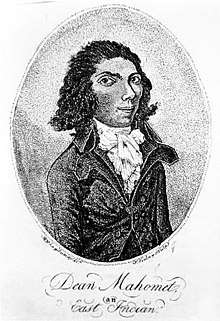

Sake Dean Mahomed by Thomas Mann Baynes (c. 1810) | |

| Born | Sheikh Din Muhammad c. May 1759 |

| Died | 24 February 1851 (aged 91) |

| Other names | Dean Mahomed Dean Mahomet Deane Mahomet Sake Dean Mohammed Sheikh Dean/Deen Mohammed "Dr. Brighton" |

Notable work | The Travels of Dean Mahomet (1794) |

| Spouse(s) | Jane Daly (m.1786–1844) Jane Jeffries (m. 1806–1850) |

| Children | Rossana Mahomed Henry Mahomed Horatio Mahomed Frederik Mahomed Arthur Mahomed Dean Mahomed Amelia Mahomed |

Early life

Born in c. May 1759 in the city of Patna,[4] then part of the Bengal Presidency in British India. He was from a Bengali Muslim family.[5] He claimed to be related to the Nawabs of Bengal, and that he had ancestors who worked in administrative service under the Mughal Emperors.[6] He belonged to the traditional Nai (barber) caste, and had studied alchemy and understood the methods used to produce various alkalis, soaps and shampoo.

Sake Dean Mahomed grew up in Patna. His father served in the British East India Company's Bengal Army and died in battle when Mahomed was about eleven years old.[5]Following his father's death, he was taken under the wing of Captain Godfrey Evan Baker, an Anglo-Irish Protestant officer. Mahomed served in the army of the East India Company as a trainee surgeon and served against the Marathas. Mahomed also mentions how Mir Qasim and most of the entire Bengali Muslim aristocracy had lost their famed wealth. He complained about Shuja-ud-Daula's campaign against his Rohilla allies and how Hyder Ali defeated the British during the Battle of Pollilur. Mahomed remained with Captain Baker until 1782, when the Captain resigned. That same year, Mahomed also resigned from the Army, choosing to accompany Baker, 'his best friend', to Ireland.[7]

Adult life and Family

In 1784, Mahomed emigrated to Cork, Ireland, with the Baker family.[7] There he studied to improve his English language skills at a local school, and fell in love with Jane Daly, a "pretty Irish girl of respectable parentage". The Daly family was opposed to their relationship, so the couple eloped to another town to get married in 1786.[7][8] Mahomed and Daly were married in the Diocese of Cork & Ross in Cork, Ireland.[9] At that time it was illegal for Protestants to marry non-Protestants, so Mahomed converted to Anglicanism to marry Jane Daly (1761-1844).[10] They moved to 7 Little Ryder Street in London, England, at the turn of the 19th century."[11][12]

According to leading scholars, and as indicated by parish records in London, Mahomed conducted a bigamous marriage in Marylebone in 1806 to Jane Jeffreys (1780-1850); the banns were read on 24 August for Jane and "William Mahomet."[13][14] He had a daughter, Amelia (b. 1808) by her and is listed as the father "William Dean Mahomet" in the parish register.[15][16] Amelia was baptised on 11 June 1809 at St Marylebone, Westminster, in London.[16] By his legal wife, Sake Dean Mahomed had seven children: Rosanna, Henry, Horatio, Frederick, Arthur,[8] and Dean Mahomed (baptised in the Roman Catholic church of St. Finbarr's, Cork, in 1791).[17]

His son, Frederick, was a proprietor of Turkish baths at Brighton[18] and also ran a boxing and fencing academy near Brighton. His most famous grandson, Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar Mahomed (c. 1849–1884), became an internationally known physician[8] and worked at Guy's Hospital in London. He made important contributions to the study of high blood pressure.[19] Another of Sake Dean Mahomed's grandsons, Rev. James Kerriman Mahomed, was appointed as the vicar of Hove, Sussex, in the late 19th century.[8]

The Travels of Dean Mahomet

On 15 January 1794, Mahomed published his travel book, entitled The Travels of Dean Mahomet. The book is in epistolary form as was common for travel books and many novels in that era and consists of 38 letters.[20] the book begins with a brief introduction where he contrasts Ireland and India, writing that "the face of every thing about me [is] so contrasted to those striking scenes in India."[21] and proceeds to give a sketch of his early years. He then describes his travels over the period 1770 to 1775 as a camp follower to the Bengal army as it moved around North East India. A series of military conflicts are described along with descriptions of some major cities, including Kolkata (Calcutta) and Varanasi (Benares). This is accompanied by first hand accounts of Indian culture, trade, military conflicts, food, wildlife, etc.[22] The book concludes with a description of Mahomed's voyage to Britain where he arrived at Dartmouth in September 1784. While Mahomed gives an insightful and sympathetic account of India and Indian customs, as Mona Narain points out this is done from an essentially British cultural perspective - he consistently uses the pronoun "we" to describe himself and Europeans, and does not challenge the basic legitimacy of colonial rule in India.[23] The historian Michael Fisher, who published a biographical essay to accompany an edition of the book, suggested that some passages in the book were closely paraphrased from other travel narratives written in the late 18th century.[24]

Restaurant venture

.jpg)

In 1810, after moving to London, Sake Dean Mahomed opened the first Indian restaurant in England: the Hindoostane Coffee House in George Street, near Portman Square, Central London.[25] The restaurant offered, among other items, hookah "with real chilm tobacco, and Indian dishes, ... allowed by the greatest epicures to be unequalled to any curries ever made in England." This venture came to an end due to financial difficulties.[15]

Introduction of shampooing to Europe

Before opening his restaurant, Mahomed had worked in London for nabob, Basil Cochrane, who had installed a steam bath for public use in his house in Portman Square and promoted its medical benefits. Mahomed may have been responsible for introducing the practice of champooi or "shampooing" (or Indian massage) there. In 1814, Mahomed and his wife moved back to Brighton and opened the first commercial "shampooing" vapour masseur bath in England, on the site now occupied by the Queen's Hotel. He described the treatment in a local paper as "The Indian Medicated Vapour Bath (type of Turkish bath), a cure to many diseases and giving full relief when every thing fails; particularly Rheumatic and paralytic, gout, stiff joints, old sprains, lame legs, aches and pains in the joints".[26] This business was an immediate success and Dean Mahomed became known as "Dr. Brighton". Hospitals referred patients to him and he was appointed as shampooing surgeon to both King George IV and William IV.[26]

_-_BL.jpg)

The literary critic Muneeza Shamsie notes that Mahomed wrote two books connected to his burgeoning trade.[26] The first was Cases Cured by Sake Deen Mahomed, Shampooing Surgeon, and Inventor of the Indian Medicated Vapour and Sea-Water Bath (1820), while the second, Shampooing; or, benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath, went through three editions (1822, 1826, 1838) and was dedicated to King George IV.[27][14] In this work, Mahomed speaks of the initial resistance to the idea of shampooing among the English he encountered in his new country: "It is not in the power of any individual to give unqualified satisfaction, or to attempt to establish a new opinion without the risk of incurring the ridicule, as well as censure, of some portion of mankind. So it was with me: in the face of indisputable evidence, I had to struggle with doubts and objections raised and circulated against my Bath, which, but for the repeated and numerous cures effected by it, would long since have shared the common fate of most innovations in science."[28]

Death

Mahomed died on 24 February 1851[4] (aged 91–92) at 32 Grand Parade, Brighton. He was buried in a grave at St Nicholas Church, Brighton, in which his son Frederick was later interred. Frederick taught fencing, gymnastics and other activities in Brighton at a gymnasium he built on the town's Church Street.[29]

Recognition

By the Victorian period, Sake Dean Mahomed had begun to lose prominence as a public figure and until the scholarly interventions of the last fifty years was largely forgotten by history. The modern renewal of interest in his writings developed after poet and scholar Alamgir Hashmi drew attention to this author in the 1970s and 1980s. Michael H. Fisher has written a book on Sheikh Dean Mahomet entitled The First Indian Author in English: Dean Mahomed in India, Ireland, and England (Oxford University Press, Delhi, 1996). Additionally, Rozina Visram's Ayahs, Lascars and Princes: The Story of Indians in Britain 1700–1947 (1998) was highly influential in drawing public attention to Mahomed's life and work.[30]

Several commemorations of and tributes to Mahomed's legacy have taken place in the 21st century. On 29 September 2005 the City of Westminster unveiled a Green Plaque commemorating the opening of the Hindoostane Coffee House.[25] The plaque is at 102 George Street, close to the original site of the coffee house at 34 George Street.[31] On 15 January 2019, Google recognised Sake Dean Mahomed with a Google Doodle on the main page.[32]

See also

Published works

- The Travels of Dean Mahomet, a Native of Patna in Bengal, Through Several Parts of India, While in the Service of the Honourable the East India Company. Cork: J. Connor. 1794.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Michael Herbert, ed. (1997). The Travels of Dean Mahomet: An Eighteenth-Century Journey Through India. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-20717-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shampooing; or, benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath. Brighton: Creasy & Baker. 1823.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Shampooing; or, Benefits resulting from the use of the Indian medicated vapour bath (3rd ed.). Bath: Wm. Fleet. 1838.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

References

Notes

- The word "shampoo" did not take on its modern meaning of washing the hair until the 1860s. See p. 197 in The travels of Dean Mahomet, and "shampoo", v., entry, p. 167, Oxford English Dictionary, 2nd ed., vol. 15, ISBN 0-19-861227-3.

Citations

- Mahomet 1794, pp. 148–149, 155–156, 160.

- Fisher 2000.

- "Sake Dean Mahomed, The first Indian to publish a book in English". Devdiscourse News. 15 January 2019. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- Dean Mahomed at Find a Grave

- Mahomet, Sake Deen, 1759-1851. (1997). The travels of Dean Mahomet : an eighteenth-Century journey through India. Fisher, Michael Herbert, 1950-. Berkeley: University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-91851-1. OCLC 44955950.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Das 2016, pp. 199-211.

- Husainy, Abi (6 November 2013). "Dean Mahomed's Early Life in India". Moving Here: Tracing Your Roots. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- Ansari 2004, p. 58.

- Platt, Lyman (1999). "Irish Records Extraction Database". Ancestry.com.

- Mahomet 1997, Ch. 3 Dean Mahomet in Ireland and England (1784–1851).

- Ansari 2004, p. 57–58.

- "London, England, City Directories, 1736-1943". ancestry.com. Retrieved 20 February 2019.

- London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Reference Number: p89/mry1/288. Ancestry.com. London, England, Church of England Marriages and Banns, 1754-1932 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Church of England Parish Registers. London Metropolitan Archives, London.

- Fisher 2014, p. 128.

- Husainy, Abi (7 November 2013). "Dean Mahomed in London". Moving Here: Tracing Your Roots. Archived from the original on 7 November 2013. Retrieved 15 January 2019.

- London Metropolitan Archives; London, England; Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812; Reference Number: P89/MRY1/084. Ancestry.com. London, England, Church of England Baptisms, Marriages and Burials, 1538-1812 [database on-line]. Provo, UT, USA: Ancestry.com Operations, Inc., 2010. Original data: Church of England Parish Registers, 1538-1812. London, England: London Metropolitan Archives.

- "Dean Mahomed baptism". Irish Genealogy. Retrieved 25 February 2015.

- "Mahomed, Frederick Henry Horatio Akbar". Royal College of Physicians. 24 May 2005. Archived from the original on 6 October 2007. Retrieved 10 January 2009.

- O'Rourke 1992, pp. 212–213.

- Fisher, Michael H. (1998). "Representations of India, the English East India Company, and Self by an Eighteenth-Century Indian Emigrant to Britain". Modern Asian Studies. 32 (4): 891–911. doi:10.1017/S0026749X9800314X. ISSN 0026-749X. JSTOR 313054.

- Mahomet 1794, Letter I: when I first came to Ireland, I found the face of every thing about me so contrasted to those striking scenes in India

- Mahomet 1794.

- Narain, Mona (2009). "Dean Mahomet's "Travels", Border Crossings, and the Narrative of Alterity". Studies in English Literature, 1500-1900. 49 (3): 693–716. ISSN 0039-3657. JSTOR 40467318.

- Fisher 1998 p. 138-140.

- "Curry house founder is honoured". BBC News. 29 September 2005. Retrieved 9 October 2008.

- Teltscher 2000, pp. 409-423.

- Mahomed 1838, p. iii.

- Mahomed 1838, p. vii.

- Collis 2010, p. 187.

- Zarr, Gerald (March 2018). "The Shampooing Surgeon of Brighton". Aramco World.

- "Westminster Green Plaques" (PDF). City of Westminster. Retrieved 10 September 2019.

- "Celebrating Sake Dean Mahomed". google.com.

Sources

- Ansari, Humayun (2004). The Infidel Within: The History of Muslims in Britain, 1800 to the Present. C. Hurst & Co. Publishers. ISBN 978-1-85065-685-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Collis, Rose (2010). The New Encyclopaedia of Brighton. (based on the original by Tim Carder) (1st ed.). Brighton: Brighton & Hove Libraries. ISBN 978-0-9564664-0-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Das, Alok (2016). "Life and Legacy of Sake Dean Mahomet: A Forgotten Enigma". Communication Studies and Language Pedagogy. 2 (1–2): 199–211.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Michael H. (2000). The First Indian Author in English: Dean Mahomed (1759-1851) in India, Ireland, and England. Oxford University Press. ISBN 9780195638998.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Fisher, Michael H. (2014). "South Asians in Britain up to the 1850s". In Chatterji, Joya; Washbrook, David (eds.). 'Routledge Handbook of the South Asian Diaspora. Routledge.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- O'Rourke, Michael F. (1992). "Frederick Akbar Mahomed". Hypertension. 19 (2): 212–217. doi:10.1161/01.hyp.19.2.212. PMID 1737655.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Teltscher, Kate (2000). "The Shampooing Surgeon and the Persian Prince: Two Indians in Early Nineteenth-century Britain". Interventions: International Journal of Postcolonial Studies. 2 (3): 409–23. doi:10.1080/13698010020019226.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Sake Dean Mahomed. |

- Celebrating Sake Dean Mahomed at Google Doodle

- Web version of The Travels of Dean Mahomet

- Works by or about Sake Dean Mahomed at Internet Archive

- Works by or about Sake Dean Mahomed at HathiTrust

- Plaque #3165 on Open Plaques, Retrieved 19 January 2019.

- "Sake Dean Mahomet, Europe's first Asian Shaikh", The News International, Pakistan

- "Making History – Sake Dean Mahomed – Regency 'Shampooing Surgeon'", BBC – Beyond the Broadcast

- Black History in Brighton

- Sake Dean Mahomed

- Sake Dean Mahomed