Cricosaurus

Cricosaurus is an extinct genus of marine crocodyliforms of the Late Jurassic, belonging to the family Metriorhynchidae. The genus was established by Johann Andreas Wagner in 1858 for three skulls from the Tithonian (Late Jurassic) of Germany.[3] The name Cricosaurus means "Ring lizard", and is derived from the Greek Cricos- ("ring") and σαῦρος -sauros ("lizard").

| Cricosaurus | |

|---|---|

| |

| C. suevicus skeleton | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Reptilia |

| Suborder: | †Thalattosuchia |

| Family: | †Metriorhynchidae |

| Tribe: | †Rhacheosaurini |

| Genus: | †Cricosaurus Wagner, 1858 |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

Discovery

Cricosaurus was first named by Wagner in 1858,[3] as a reclassification of a specimen he had previously described in 1852 ("Stenosaurus" elegans, "Stenosaurus" being a misspelling of Steneosaurus).[4]

Distribution

Several other species have since been named, including C. suevicus by Fraas in 1901 (originally as a species of Geosaurus).[5] One former species, C. medius (named by Wagner in 1858) has since been reclassified as a junior synonym of Rhacheosaurus gracilis.[6] Fossil specimens referrable to Cricosaurus are known from Late Jurassic deposits in England, France, Switzerland, Germany,[7][8] Argentina (Vaca Muerta),[9] and Mexico (La Caja and Pimienta Formations).[10]

Classification

The original three skulls (all assigned to different species) were poorly known, and the genus had been considered a junior synonym of Metriorhynchus, Geosaurus or Dakosaurus by different palaeontologists in the past.[7] Some phylogenetic analysis did not support the monophyly of Cricosaurus,[11] However, a more comprehensive analysis in 2009 showed that the species contained in Cricosaurus were valid, and furthermore that several long-snouted species formerly classified in the related genera Geosaurus, Enaliosuchus and Metriorhynchus were in fact more closely related to the original specimens of Cricosaurus, and thus were re-classified into this genus.[6]

Cladogram after Cau & Fanti (2010).[12]

| Cricosaurus |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

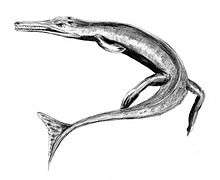

All currently known species would have been three metres or less in length. When compared to living crocodilians, Cricosaurus can be considered moderate to small-sized. Its body was streamlined for greater hydrodynamic efficiency, which along with its finned tail made it a more efficient swimmer than modern crocodilian species.[13]

Salt glands

Recent examination of the fossil specimens of Cricosaurus araucanensis have shown that both juveniles and adults of this species had well-developed salt glands. This means that it would have been able to "drink" salt-water from birth (necessary for a pelagic animal) and eat prey that have the same ionic concentration as the surrounding sea water (i.e. cephalopods) without dehydrating.[14][15] Adult specimens of Metriorhynchus also have these well-developed salt glands.[16]

Niche partitioning

Several species of metriorhynchids are known from the Mörnsheim Formation (Solnhofen limestone, early Tithonian) of Bavaria, Germany: Cricosaurus suevicus, Dakosaurus maximus, Geosaurus giganteus and Rhacheosaurus gracilis. It has been hypothesised that niche partitioning enabled several species of crocodyliforms to co-exist. The top predators of this Formation appear to be D. maximus and G. giganteus, which were large, short-snouted species with serrated teeth. The long-snouted C. suevicus and R. gracilis would have fed mostly on fish, although the more lightly built Rhacheosaurus may have specialised towards feeding on small prey. In addition to these four species of metriorhynchids, a moderate-sized species of Steneosaurus was also contemporaneous.[17]

From the slightly older Nusplingen Plattenkalk (late Kimmeridgian) of southern Germany, both C. suevicus and Dakosaurus maximus are contemporaneous. As with Solnhofen, C. suevicus feed upon fish, while D. maximus was the top predator.[18]

Possible viviparity

The hip of Cricosaurus araucanensis contains several features that create an unusually large pelvic opening. The acetabulum, or femur articulation on the hip, is placed very far towards of the bottom of the body relative to the vertebral column, and the sacral ribs are angled downwards at 45°, further increasing the distance between the vertebral column and the pubis-ischium. The hip was effectively a vertical ellipse in cross-section, being 120 millimetres (4.7 in) tall and 100 millimetres (3.9 in) wide. In other pseudosuchians like Steneosaurus, Machimosaurus, and Pelagosaurus, the sacral ribs are less angled and more horizontal; in this way, Cricosaurus is actually more similar to aquatic reptiles like Chaohusaurus, Utatsusaurus, and Keichousaurus, the latter of which live birth has been suggested for. In an evaluation of different reproductive hypotheses for Cricosaurus and other metriorhynchids, Herrera et al. considered viviparity more likely than oviparity.[19]

References

- Yanina Herrera, Zulma Gasparini and Marta S. Fernández (2013). "A new Patagonian species of Cricosaurus (Crocodyliformes, Thalattosuchia): first evidence of Cricosaurus in Middle–Upper Tithonian lithographic limestone from Gondwana". Palaeontology. 56 (3): 663–678. doi:10.1111/pala.12010.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Koken E. 1883. Die Reptilien der norddeutschen unteren Kreide. Zeitschrift der deutschen Geologischen Gesellschaft 35: 735-827.

- Wagner A. 1858. Zur Kenntniss der Saurier aus den lithographischen Schiefern. Abhandlungen der Mathemat.-Physikalischen Classe der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 8: 415-528.

- Wagner A. 1852. Neu-aufgefundene Saurier-Überreste aus dem lithographischen Schiefern und dem oberen Jurakalk. Abhandlungen der Mathemat.-Physikalischen Classe der Königlich Bayerischen Akademie der Wissenschaften 6: 661-710.

- Fraas E. 1901. Die Meerkrokodile (Thalattosuchia n. g.) eine neue Sauriergruppe der Juraformation. Jahreshefte des Vereins für vaterländische Naturkunde, Württemberg 57: 409-418.

- Young, M.T. and de Andrade, M.B. (2009). "What is Geosaurus? Redescription of Geosaurus giganteus (Thalattosuchia: Metriorhynchidae) from the Upper Jurassic of Bayern, Germany." Zoological Journal of the Linnean Society, 157: 551-585.

- Steel R. 1973. Crocodylia. Handbuch der Paläoherpetologie, Teil 16. Stuttgart: Gustav Fischer Verlag, 116 pp.

- Sachs, S.; Young, M.T.; Abel, P.; Mallison, H. (2019). "A new species of the metriorhynchid crocodylomorph Cricosaurus from the Upper Jurassic of southern Germany" (PDF). Acta Palaeontologica Polonica. 64 (X): xxx–xxx. doi:10.4202/app.00541.2018.

- Gasparini ZB, Dellapé D. 1976. Un nuevo cocodrilo marino (Thalattosuchia, Metriorhynchidae) de la Formación Vaca Muerta (Jurasico, Tithoniano) de la Provincia de Neuquén (República Argentina). Congreso Geológico Chileno 1: c1-c21.

- Frey, E., Buchy, M.-C., Stinnesbeck, W. & López-Oliva, J.G. 2002. Geosaurus vignaudi n. sp. (Crocodylia, Thalattosuchia), first evidence of metriorhynchid crocodilians in the Late Jurassic (Tithonian) of central-east Mexico (State of Puebla). Canadian Journal of Earth Sciences 39: 1467–1483.

- Young MT. 2007. The evolution and interrelationships of Metriorhynchidae (Crocodyliformes, Thalattosuchia). Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 27 (3): 170A.

- Andrea Cau; Federico Fanti (2010). "The oldest known metriorhynchid crocodylian from the Middle Jurassic of North-eastern Italy: Neptunidraco ammoniticus gen. et sp. nov". Gondwana Research. 19 (2): 550–565. doi:10.1016/j.gr.2010.07.007.CS1 maint: uses authors parameter (link)

- Massare JA. 1988. Swimming capabilities of Mesozoic marine reptiles; implications for method of predation. Paleobiology 14 (2):187-205.

- Fernández M, Gasparini Z. 2000. Salt glands in a Tithonian metriorhynchid crocodyliform and their physiological significance. Lethaia 33: 269-276.

- Fernández M, Gasparini Z. 2008. Salt glands in the Jurassic metriorhynchid Geosaurus: implications for the evolution of osmoregulation in Mesozoic crocodyliforms. Naturwissenschaften 95: 79-84.

- Gandola R, Buffetaut E, Monaghan N, Dyke G. 2006. Salt glands in the fossil crocodile Metriorhynchus. Journal of Vertebrate Paleontology 26 (4): 1009-1010.

- Andrade MB, Young MT. 2008. High diversity of thalattosuchian crocodylians and the niche partition in the Solnhofen Sea Archived 2011-06-03 at the Wayback Machine. The 56th Symposium of Vertebrate Palaeontology and Comparative Anatomy

- Dietl G, Dietl O, Schweigert G, Hugger R. 2000. Der Nusplinger Plattenkalk (Weißer Jura zeta) - Grabungskampagne 1999.

- Herrera, Y.; Fernandez, M.S.; Lamas, S.G.; Campos, L.; Talevi, M.; Gasparini, Z. (2017). "Morphology of the sacral region and reproductive strategies of Metriorhynchidae: a counter-inductive approach". Earth and Environmental Science Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 106 (4): 247–255. doi:10.1017/S1755691016000165.