Concerns and controversies at the 2020 Summer Olympics

A number of concerns and controversies have arisen in relation to the 2020 Summer Olympics, which are due to be hosted in Tokyo, Japan.

| Part of a series on |

|

There have been allegations of bribery in the Japanese Olympic Committee's (JOC) bid for the Games, of plagiarism in the initial design for the Games' logo, and of illegal overwork by dozens of companies involved in construction for the Games. Notable safety concerns for athletes have included radiation levels from the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, water quality, and expected heat levels. Political controversies include the use of maps showing disputed territories as part of Japan, and a refusal to ban the rising sun flag at Olympic venues.

A more recent concern is the ongoing coronavirus pandemic, which originated in Wuhan, China. It has resulted in the Games being postponed until 2021.

Organisational issues and controversies

Bribery and corruption

In January 2016, the second part of a World Anti-Doping Agency (WADA) commission report into corruption included a footnote detailing a conversation between Khalil Diack, son of former International Association of Athletics Federations (IAAF) President Lamine Diack, and Turkish officials from the Istanbul bid team.[1] A transcript of the conversation cited in the report suggested that a "sponsorship" payment of between US$4 million and 5 million had been made by the Japanese bid team "either to the Diamond League or IAAF".[1] The footnote claimed that because Istanbul did not make such a payment, the bid lost the support of Lamine Diack. The WADA declined to investigate the claim because it was, according to its independent commission, outside the agency's remit.[1]

In July and October 2013 (prior to, and after, being awarded the Games), Tokyo made two bank payments totaling 2,800,000 Singapore dollars million to a Singapore-based company known as Black Tidings. The company is tied to Papa Massata Diack, a son of Lamine Diack who worked as a marketing consultant for the IAAF, and is being pursued by French authorities under allegations of bribery, corruption, and money laundering.[2] Black Tidings is held by Ian Tan Tong Han, a consultant to Athletics Management and Services—which manages the IAAF's commercial rights and has business relationships with Japanese firm Dentsu. Black Tidings has also been connected to a doping scandal involving the Russian athletics team.[2][3][4]

Japanese Olympic Committee (JOC) and Tokyo 2020 board member Tsunekazu Takeda stated that the payments were for consulting services, but refused to discuss the matter further because it was confidential. Toshiaki Endo called on Takeda to publicly discuss the matter. Massata Diack denied that he had received any money from Tokyo's organising committee.[2][4] The International Olympic Committee (IOC) established a team to investigate these matters, and will closely follow the French investigation.[5]

In January 2019, a source revealed that Takeda was being formally investigated over alleged corruption.[6] On the 19 March 2019, Takeda resigned from the JOC.[7]

In November 2019, it was reported that the Tokyo's Olympic bid committee's accounting documents, detailing over 900 million yen (≈ 8 million US$) spent on overseas consultancy firms for Tokyo's 2020 Olympics hosting bid, were missing.[8]

Logo plagiarism

The initial designs for the official emblems of the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics were unveiled on 24 July 2015. The logo resembled a stylised "T": a red circle in the top-right corner representing a beating heart, the flag of Japan, and an "inclusive world in which everyone accepts each other"; and a dark grey column in the centre representing diversity.[9] The Paralympic emblem inverted the light and dark columns of the pattern to resemble an equal sign.[10]

Shortly after the unveiling, Belgian graphics designer Olivier Debie accused the organising committee of plagiarising a logo he had designed for the Théâtre de Liège, which aside from the circle, consisted of nearly identical shapes. Tokyo's organising committee denied that the emblem design was plagiarised, arguing that the design had gone through "long, extensive and international" intellectual property examinations before it was cleared for use.[11][12] Debie filed a lawsuit against the IOC to prevent use of the infringing logo.[13]

The emblem's designer, Kenjirō Sano, defended the design, stating that he had never seen the Liège logo, while the Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games (TOCOG) released an early sketch of the design that emphasised a stylised "T" and did not resemble the Liège logo.[13] However, Sano was found to have had a history of plagiarism allegations, with others alleging his early design plagiarised work of Jan Tschichold, and that he used a photo without permission in promotional materials for the emblem, along with other past cases.[13] On 1 September 2015, following an emergency meeting of TOCOG, Governor of Tokyo Yōichi Masuzoe announced that they had decided to scrap Sano's two logos. The committee met the following day to decide how to develop a new logo design.[13]

On 24 November 2015, an Emblems Selection Committee was established to organize an open call for design proposals, open to Japanese residents over the age of 18, with a deadline set for 7 December 2015. The winner would receive ¥1 million and tickets to the opening ceremonies of both the 2020 Summer Olympics and Paralympics.[14][15][16] On 8 April 2016, a new shortlist of four pairs of designs for the Olympics and Paralympics were unveiled by the Emblems Selection Committee; the Committee's selection—with influence from a public poll—was presented to TOCOG on 25 April 2016 for final approval.[15]

The new emblems for the 2020 Olympics and Paralympics were unveiled on 25 April 2016. Designed by Asao Tokolo, winner of the nationwide design contest, the emblems take the form of a ring in an indigo-colored checkerboard pattern. The design is meant to "express a refined elegance and sophistication that exemplifies Japan".[17]

Stadium design plagiarism

After Tokyo submitted their bid for the 2020 Summer Olympics, there was talk of possibly renovating or reconstructing the National Olympic Stadium. The stadium would host the opening and closing ceremonies as well as track and field events.[18]

It was confirmed in February 2012 that the stadium would be demolished and reconstructed, and receive a £1 billion upgrade. In November 2012, renderings of the new national stadium were revealed, based on a design by architect Zaha Hadid. The stadium was demolished in 2015 and the new one was originally scheduled to be completed in March 2019.[19] The new stadium will be the venue for athletics, rugby, some football games, and the opening and closing ceremonies of the Olympics and Paralympics.[20]

Due to budget constraints, the Japanese government announced several changes to Hadid's design in May 2015, including cancelling plans to build a retractable roof and converting some permanent seating to temporary seating.[21] The site area was also reduced from 71 to 52 acres. Several prominent Japanese architects, including Toyo Ito and Fumihiko Maki, criticized Hadid's design, with Ito comparing it to a turtle and Maki calling it a white elephant; others criticized the stadium's encroachment on the outer gardens of the Meiji Shrine. Arata Isozaki, on the other hand, commented that he was "shocked to see that the dynamism present in the original had gone" in the redesign of Hadid's original plan.[22]

After the futuristic Olympic stadium design by the British architect Zaha Hadid were ditched for cost-related reasons, new design by the Japanese architect Kengo Kuma faced plagiarism accusations due to its similarities to Hadid's original blueprint.[23][24] Kuma admitted that there are similarities, but denied copying the work of Hadid.[25][26]

Environment, health and safety concerns

COVID-19 pandemic and other contagion risks

The COVID-19 pandemic itself has been a concern for the 2020 Summer Olympics which is scheduled to take place in Tokyo starting end of July, and due to the Olympics the country's government has been taking extra precautions to help minimise the outbreak's worst impact.[27][28] The Tokyo organising committee and the International Olympic Committee have been monitoring the outbreak's impact in Japan.[27] Wuhan, the source of the outbreak, is located approximately 2,400 kilometers from Tokyo.

In the run-up to the Olympics, the Japanese Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has been carrying out catch-up vaccinations for the large portions of the Japanese population left unprotected from common infectious diseases at the inoculation over the last few decades.[29] For example, Japan has no mandatory mumps vaccination and is fourth in the world in mumps cases, after China, Nepal and Burkina Faso, according to data from the World Health Organization (WHO).[29]

Following the outbreaks of rubella in Japan, which prompted the Centers for Disease Control and Prevention (CDC) to warn pregnant women of travel to Japan in 2018, the country's Ministry of Health, Labour and Welfare has been conducting inoculation of middle-aged men who had been left out of rubella vaccinations in the 1970s and 1980.[29]

In a February 2020 interview with City A.M., the Conservative London mayoral candidate Shaun Bailey argued that London would be able to host the Olympic Games at the former London 2012 Olympic venues, should the Games need to be moved due to the ongoing disruption caused by the coronavirus outbreak.[30] Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike criticised Bailey's comment as inappropriate.[31] The organisers said on 3 March that the Olympics will go on as planned.[32]

On 20 March 2020, the World Anti Doping Agency noted that the coronavirus outbreak was seriously affecting doping tests in advance of the games.[33] The IOC regulations required extensive testing in the months prior to the event. China had temporarily stopped testing in February,[34] and the United States, France, Great Britain and Germany had reduced testing by March. European anti-doping agencies raised concerns that blood and urine tests could not be performed, and that mobilizing the staff necessary to do so before the end of the pandemic would be a health risk.[33]

On March 24, due to the coronavirus spreading rapidly, the Summer Olympics will now be pushed back to 2021, still being held in Tokyo.[35]

There was speculation that the Japanese government was repressing the extent of the infection to make sure that the 2020 Tokyo Olympic Games would be held on schedule. Japan's former prime minister Yukio Hatoyama suggested that the number of confirmed cases was downplayed by the Japanese government in order to preserve the Olympics as scheduled, adding that Tokyo Governor Yuriko Koike put the 2020 Olympics first rather than Tokyo citizens first.[36] The country saw a sudden rise in COVID-19 cases after the postponement was announced, but health minister Katsunobu Kato denied the rumour that the postponement of the Olympics was tied to the spike in confirmed cases.[37]

In April, Will Ripley, a correspondent for CNN, said in the early weeks of the coronavirus pandemic, the Japanese government was fighting to save Tokyo Olympics 2020, as other countries were taking aggressive measures to fight COVID19. [38] He also mentioned that the confirmed COVID-19 cases suddenly increased after the postponement of the Olympics was announced, pointing out that Japan's approach kept cases low so that the Japanese government could save Tokyo 2020. [39]

Fukushima radiation

The Tokyo Organising Committee of the Olympic and Paralympic Games announced that the Olympics torch relay will begin in Fukushima, and the Olympic baseball and softball matches will be played at Fukushima Azuma Baseball Stadium, 55 miles (89 km) from the site of the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster, despite the fact that the scientific studies on the safety of Fukushima are currently in dispute.[40][41] In relation to the 2011 Tōhoku earthquake and tsunami, which resulted in multiple nuclear meltdowns and an official Level 7 disaster, officials from the World Health Organization (WHO) and the United Nations have determined that the risks of dangerous radiation exposure are minimal.[42] Nevertheless, some scientists and citizens remain skeptical.[43][44][45]

For example, Tilman Ruff, a public health expert and a co-founder of the Nobel Peace Prize-winning International Campaign to Abolish Nuclear Weapons (ICAN), urged the Australian Olympic Committee to properly inform its staff and athletes attending the 2020 Tokyo Games about the ongoing health effects of the Fukushima radiation.[46]

Former nuclear industry executive and whistle blower Arnold Gundersen and his institute, Fairewinds Associates, tested for the presence of radioactive dust on land scheduled to be used for certain events, including baseball, softball and the Olympic torch relay.[47] At these facilities, the legally allowable radiation levels are higher than at other athletic facilities.[48] According to certain models, such as the National Academy of Sciences' "linear, no-threshold" model, small increases in radiation exposure may cause proportional health risks.[49] The Japanese government posted that measured radiation levels in the city of Fukushima are comparable with safe readings in Hong Kong and Seoul, while Tokyo's readings are even lower, in line with Paris and London.[50] However, the data collected by the monitoring posts installed by the Japanese governments are partial and non-representative of the extent of radioactive contamination, as they measure only the atmospheric radiation levels in the form of gamma rays, but not radionuclides, such as cesium-137, which emit alpha and beta particles that are dangerous when inhaled or ingested.[50] It is also pointed out that the government-installed monitoring posts are placed strategically and the areas surrounding the posts were cleaned so that the radiation levels remain lower.[50] Greenpeace reported that the radiation levels measured around the J-Village sports camp in Fukushima, where the Tokyo 2020 Olympic torch relay will begin, were 1,700 times higher than before the Fukushima Daiichi nuclear disaster.[51][52][53] Even though the Japanese government promised to keep the radiation levels below 0.23 µSv per hour, radiation hot spots at the J-Village showed readings as high as 1.7 µSv per hour at 1 metre (3 ft 3 in) above the surface and over 71 µSv per hour at the surface level.[51][52][53]

Additionally, food from the region, currently under import restrictions in 23 countries,[54] is tested intensively for safety.[55] In October 2019, after tons of poorly-secured radioactive Fukushima waste were swept away by typhoon Hagibis,[56] IOC chief Thomas Bach promised to carry out inspections on radiation safety.[57]

In November 2019, a Japanese citizens' group Minna-No Data Site (Everyone's Data Site) published an English version of Citizens' Radiation Data Map of Japan, a 16-page booklet featuring radiation-level maps, created using soil samples from 3,400 sites in 17 prefectures in eastern Japan, the results of three-year land contamination surveys with approximately 4,000 volunteers.[58]

Heat and air-conditioning

Tokyo's bid to host the Summer Olympics played down concerns over heat, with the proposal reading "With many days of mild and sunny weather, this period provides an ideal climate for athletes to perform at their best". However, Tokyo 2020 is expected to be the hottest Olympics ever,[59] due to the urban heat island effect and climate change.[60]

In October 2019, the International Olympic Committee announced plans for moving the Olympic marathon and race walking to Sapporo, more than 800 kilometres (500 mi) further north from Tokyo, in a bid to avoid heat.[61] The Tokyo Metropolitan Government strongly opposed the IOC's decision, suggesting to move the marathon start time up one hour to 5:00 a.m.,[62] while Sapporo welcomed the IOC announcement.[63] In October 2019, Japanese politician Shigefumi Matsuzawa wrote to IOC chief Thomas Bach to move the Olympic golf tournaments, scheduled to take place at Kasumigaseki Golf Club in Saitama Prefecture, about 50 kilometres (31 mi) northwest of Tokyo, to a region with fewer heat problems.[64]

Concern over indoor temperatures has also been raised, since, for cost reduction, Tokyo's New National Stadium was built without an air conditioner, and the roof was constructed over the spectator seating only.[65] Additionally, a sports museum and sky walkway that were part of the scrapped design were eliminated, while VIP lounges and seats were reduced, along with reduced underground parking facilities. These reductions result in a site of 198,500 square meters, 13% less than originally planned. Air conditioning for the stadium was also abandoned upon request of Japanese Prime Minister Shinzō Abe, and when asked about the abandonment Minister for the Olympics Toshiaki Endo stated that, "Air conditioners are installed in only two stadiums around the world, and they can only cool temperatures by 2 or 3°C".[66]

In December 2019, the Asahi Shimbun reported that, due to the dangers of hyperthermia, 206 primary schools in 24 out of 50 wards in Tokyo Prefecture had given up their tickets to the Olympic and Paralympic games, which had been allocated to children by the government.[67] Also, 101 additional schools told Asahi that they were considering giving up their tickets.[67] According to the report, more than 70% of the private primary schools in Tokyo are planning to refrain from taking students to the Olympic and Paralympic games.[67]

Water quality and temperatures

The sea off the Odaiba Marine Park in Tokyo Bay, the venue for the Olympic and Paralympic triathlons, has been reported to contain high levels of faecally-derived coliform bacteria.[68][69]

On 17 August 2019, the Paratriathlon World Cup scheduled at the venue was cancelled due to a high concentration of E. coli bacteria in the water.[70] In the same year, some triathletes who competed in the world triathlon mixed-relay event at the park complained about the water's foul odor, saying that it "smelt like a lavatory".[71] Scientists also urged the Olympic organisers to abandon the venue.[71] In the same month, Ous Mellouli, Yumi Kida and other athletes who participated an Olympic open water test event in Odaiba Marine Park expressed their concerns over water temperature, odor, and clarity.[72] Water temperature during the event was at 30.9 °C (87.6 °F), barely inside of acceptable range for official competition by FINA: 16–31 °C (61–88 °F).[72]

In December 2019, the USA Olympic Open Water Team head coach Catherine Kase and the American Swimming Coaches Association (ASCA) requested the open water venue to be moved out of Tokyo to safer waters.[73] Saying that they "are not comfortable with the Odaiba venue", the U.S. swimmers and coaches called for a viable back-up plan for open-water venue, in case swimming in Tokyo Bay is not safe due to environmental factors, such as near danger levels of water temperatures (averaging 29–30 °C (84–86 °F) in summer 2019) and water quality issues including E. coli bacteria and water transparency problems.[74]

In February 2020, swimmer Haley Anderson voiced her concerns for the compromised water quality (E. coli), unsafe water temperature (84–86 °F (29–30 °C)), and lack of plan B venue for the Tokyo Olympics, saying the swimmers "have spoken out and gone unheard so far".[72] She also added that she is "not confident in FINA or the IOC to have the same concern for the athletes".[72]

Asbestos in Olympic venues

Asbestos, a well-known health hazard that is prohibited from being used as a building material in many countries including Japan, was found at the Tokyo Tatsumi International Swimming Center, where the Olympic water polo events will take place.[75][76] In 2017, when the asbestos was first found in fireproof material sprayed on part of the structure supporting the swimming centre's roof, the Tokyo Metropolitan Government decided to leave it, deeming that the small amount of the mineral present would not be accessible to visitors.[75][76] In 2019, after media coverage, the organisers promised to take "emergency countermeasures" to solve the problem, without specifying what actions would be taken.[75][76]

Political and human rights issues

Worker rights and safety in Olympic construction

In 2017, the suicide of a Tokyo Olympic stadium worker was linked to overwork by Japanese labor inspectors.[77] The 23-year-old man in charge of quality control of materials at the stadium construction site was found to have recorded 211 hours and 56 minutes of overtime in one month before he killed himself in March.[77][78] Later in September, inspectors found illegal overwork in almost 40 companies, 18 of which had employees working overtime of more than 80 hours per month, and several of them exceeding 150 hours.[77] According to the Building and Wood Workers' International (BWI) report on worker safety, "dangerous patterns of overwork", including cases of working up to 28 consecutive days, have been found at Tokyo Olympic construction sites.[79] Construction workers, many of whom are foreign migrant workers, are reported to have been discouraged from reporting poor working conditions, and some workers are required to purchase their protective equipment.[79]

Acknowledgement of disputed territories

Russian and South Korean officials took issue with a map of the torch relay on the Games' official website, which depicted the disputed Liancourt Rocks (territory claimed by Japan but governed by South Korea) and Kuril Islands (territory claimed by Japan but governed by Russia) as part of Japan. Maria Zakharova, spokeswoman of the Russian Ministry of Foreign Affairs, described the inclusion as "illegal", and accused the Tokyo Organising Committee of "politicising" the Games.[80][81]

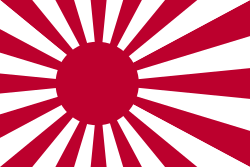

Rising sun flag

The Japanese government's refusal to ban the controversial Rising Sun Flag from Olympic venues has been characterized by some as going against the "Olympic spirit". Some East and Southeast Asian people consider the flag to be offensive due to its usage by the Imperial Japanese military during World War II, as well as its current usage by racist hate groups in Japan, such as Zaitokukai.[82][83][84][85] The flag, which has been compared by its detractors to the Nazi swastika, the U.S. Confederate flag in modern times, and the Apartheid flag of South Africa, is sometimes associated with war crimes and atrocities committed under the Empire of Japan, as well as contemporary Japan's far-right nationalist attempts to revise, deny, or romanticise its imperialistic past.[86]

The flag is currently banned by FIFA, and Japan was sanctioned by the Asian Football Confederation (AFC) after Japanese fans flew it at an AFC Champions League match in 2017.[87]

In September 2019, the South Korean parliamentary committee for sports asked the organisers of 2020 Summer Olympics in Tokyo to ban the Rising Sun Flag,[88][89] and the Chinese Civil Association for Claiming Compensation from Japan sent a letter to the International Olympic Committee asking it to ban the flag.[90]

Expressions of political opinions by athletes

The International Olympic Committee (IOC) published three pages of guidelines prohibiting athletes from using political gestures, such as kneeling, hand gestures, and disrespect during medal ceremonies. They will be allowed to express political views on traditional media and social media, and in interviews outside the Olympic Village.[91][92] The decision came under fire, with critics pointing out that IOC itself is not politically neutral, citing Adolf Hitler's actions during the 1936 Summer Olympics and the IOC's efforts to be granted U.N. Observer status during the Cold War, among other things. Tennis legend Martina Navratilova tweeted, "God how I despise these Olympic politician opportunists. I wouldn't last one day on one of these committees..."[93]

Mobilisation of Students for the Olympics

Criticism over mobilising students for the Olympic Games has been raised as students in Japanese schools whose principals have decided to accept the allocated Olympic and Paralympic tickets for school students are treated as absent from school if they do not attend the games.[94]

See also

References

- "Tokyo Olympics 2020: French prosecutors probe '$2m payment'". BBC News. 12 May 2016. Archived from the original on 13 May 2016. Retrieved 14 May 2016.

- "Tokyo Olympics: Japan to 'fully cooperate' with suspicious payments inquiry". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Life bans for three athletics figures over alleged doping cover-up". BBC Sport. 7 January 2016. Archived from the original on 9 April 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Tokyo 2020 Olympic bid leader refuses to reveal Black Tidings details". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 4 June 2016. Retrieved 6 June 2016.

- "IOC concerned at suspect payments made by Tokyo 2020 bid team". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 6 June 2016. Retrieved 7 June 2016.

- "Tokyo 2020 Games: Japan Olympics chief 'investigated in French corruption probe'". 11 January 2019.

- Wharton, David. "Embattled head of Japan's Olympic committee resigns ahead of 2020 Summer Games". Los Angeles Times. Retrieved 19 March 2019.

- Tanaka, Ryuji; Fukushima, Sachi; Oka, Daisuke (18 November 2019). "Tokyo Olympic bid committee's docs on huge consultancy fees missing". The Mainichi. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- "Tokyo 2020 unveils official emblem with five years to go". Olympic.org. Archived from the original on 10 August 2015. Retrieved 27 July 2015.

- "Tokyo 2020 launches emblems for the Olympic and Paralympic Games". IPC. Archived from the original on 27 July 2015. Retrieved 28 July 2015.

- "Tokyo Olympic Games logo embroiled in plagiarism row". The Guardian. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 3 August 2015. Retrieved 1 August 2015.

- "Tokyo Olympics emblem said to look similar to Belgian theater logo". The Japan Times. 30 July 2015. Archived from the original on 31 July 2015. Retrieved 30 July 2015.

- "Tokyo 2020 Olympics logo scrapped after allegations of plagiarism". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 2 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Tokyo 2020 Emblems Committee relax competition rules ahead of search for new logo". insidethegames.biz. Archived from the original on 10 October 2015. Retrieved 26 October 2015.

- "Japan unveils final four candidates for Tokyo 2020 Olympics logo". Japan Times. 8 April 2016. Archived from the original on 11 April 2016. Retrieved 11 April 2016.

- "Tokyo Games organizers decide to scrap Sano emblem". NHK World. 1 September 2015. Archived from the original on 4 September 2015. Retrieved 1 September 2015.

- "Checkered pattern by artist Tokolo chosen as logo for 2020 Tokyo Olympics". Japan Times. Archived from the original on 25 April 2016. Retrieved 25 April 2016.

- "Tokyo 2020 Bid Venue Could Be Renovated". GamesBids.com. 21 September 2011. Archived from the original on 3 February 2014.

- "Dazzling re-design for 2019 World Cup final venue". ESPN. 16 November 2012.

- "Venue Plan". Tokyo 2020 Bid Committee. Archived from the original on 27 July 2013. Retrieved 8 July 2013.

- "Japan plans to scale back stadium for 2020 Tokyo Olympics". AP. 18 May 2015. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Qin, Amy (4 January 2015). "National Pride at a Steep Price: Olympic Stadium in Tokyo Is Dogged by Controversy". The New York Times. Retrieved 10 June 2015.

- Platt, Kevin Holden (3 February 2016). "Tokyo Olympic Stadium Quarrel Grows". The New York Times. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Flamer, Keith (12 February 2016). "The Ugly Dust Up Over Tokyo's 2020 Olympic Stadium". Forbes. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- McCurry, Justin (15 January 2016). "Tokyo Olympic stadium architect denies copying Zaha Hadid design". The Guardian. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- Ryall, Julian (16 January 2016). "Japanese architect denies copying Zaha Hadid's Olympic stadium design". The Telegraph. Retrieved 18 December 2019.

- "Abe brushes aside worries of virus impact on Tokyo Olympics". ABC News.

- McCurry, Justin (1 February 2020). "Tokyo 2020 organisers fight false rumours Olympics cancelled over coronavirus crisis". The Guardian.

- Swift, Rocky (23 January 2020). "Coronavirus spotlights Japan contagion risks as Olympics loom". Reuters. Retrieved 23 January 2020.

- Silvester, Andy (18 February 2020). "Exclusive: Bailey calls for London to host Olympics if coronavirus forces Tokyo move". City AM. Retrieved 20 February 2020.

- "Tokyo Governor Criticizes Suggestion That London Could Host 2020 Olympics". The New York Times. 21 February 2020.

- "No plans to cancel or postpone the Tokyo 2020 Olympics". ABC News. 3 March 2020.

- Sharma, Aryan (23 March 2020). "Tokyo Olympics 2020: Coronavirus Doping Tests For Players – A Big Question Mark". essentiallysports.com.

- "Drug testing to resume in China after coronavirus outbreak". Reuters. 21 February 2020.

- Pells, Eddie (25 March 2020). "A virus rages, a flame goes out: Tokyo Games reset for 2021". AP News. Retrieved 28 March 2020.

- Coronavirus Measures Ramp Up In Japan Following Postponement Of 2020 Tokyo Olympics Forbes, 30 Mar 2020

- Tokyo's Infection Spike After Olympic Delay Sparks Questions US News, Mar 30, 2020

- Will Ripley, Twitter

- Will Ripley, Twitter

- Ryall, Julian (17 March 2017). "Anger as Fukushima to host Olympic events during Tokyo 2020 Games". The Telegraph. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Zirin, Dave; Boykoff, Jules (25 July 2019). "Is Fukushima Safe for the Olympics?". The Nation. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "WHO | Health risk assessment from the nuclear accident after the 2011 Great East Japan earthquake and tsunami, based on a preliminary dose estimation". WHO. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- "The Fukushima Nuclear Disaster and the Tokyo Olympics | The Asia-Pacific Journal: Japan Focus". apjjf.org. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- Laurie, Victoria (29 October 2019). "Warning on Fukushima fallout for Tokyo 2020 Olympians". The Australian. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- "Science students track radiation seven years after Fukushima". Agence France-Presse. 11 March 2018. Retrieved 11 November 2019 – via South China Morning Post.

- Laurie, Victoria (29 October 2019). "Warning on Fukushima fallout for Tokyo 2020 Olympians". The Australian. Retrieved 13 November 2019.

- "Atomic Balm Part 2: The Run For Your Life Tokyo Olympics". Nuclear Energy, Reactor and Radiation Facts. Retrieved 29 June 2019.

- "Atomic Balm Part 2: The Run For Your Life Tokyo Olympics - Nuclear Energy Info". Nuclear Energy, Reactor and Radiation Facts. Retrieved 13 August 2019.

- Domenici, Pete (June 2000). "Radiation Standards" (PDF). United States General Accounting Office.

- Polleri, Maxime (14 March 2019). "The Truth About Radiation in Fukushima". The Diplomat. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Radiation hotspots 'found near Fukushima Olympic site'". Agence France-Presse. 4 December 2019. Retrieved 8 December 2019 – via The Guardian.

- Tarrant, Jack (4 December 2019). "Radiation hot spots found at Tokyo 2020 torch relay start: Greenpeace". Reuters. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Cheung, Eric; Wakatsuki, Yoko (5 December 2019). "Radiation hot spots found at 2020 Olympics torch relay venue near site of nuclear disaster, Greenpeace claims". CNN. Retrieved 8 December 2019.

- Miles, Tom; Chung, Jane; Obayashi, Yuka (12 April 2019). Weir, Keith; Lawson, Hugh; Hogue, Tom (eds.). "South Korea WTO appeal succeeds in Japanese Fukushima food dispute". Reuters. Retrieved 31 October 2019.

- Denyer, Simon (August 2019). "Radioactive sushi: Japan-South Korea spat extends to Olympic cuisine". Washington Post.

- "Typhoon Hagibis sweeps away bags full of radioactive Fukushima waste as Japan's authorities say nothing to worry about (VIDEOS)". RT. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "IOC Chief Promises to Double Check Tokyo Olympics Radiation Concerns". KBS. 17 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Sekine, Shinichi (3 November 2019). "Citizens' group in Fukushima puts out radiation map in English:The Asahi Shimbun". The Asahi Shimbun. Retrieved 3 December 2019.

- Branch, John; Rich, Motoko (10 October 2019). "Tokyo Braces for the Hottest Olympics Ever". The New York Times. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Tarrant, Jack (7 August 2019). "Olympic concern as soaring temperatures in Japan kill 57 people". The Independent. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Tokyo 2020: Olympic marathon and race walks set to move to Sapporo over heat fears". BBC. 16 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "【独自】東京都「スタート時間変更」を提案 五輪マラソンでIOCに". FNN Prime (in Japanese). 21 October 2019. Archived from the original on 22 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "Sapporo mayor welcomes IOC announcement". NHK World. 17 October 2019. Archived from the original on 23 October 2019. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- Both, Andrew (31 October 2019). "Olympics: Tokyo 2020 golf must be moved because of heat, politician tells IOC". Reuters. Retrieved 9 November 2019 – via euronews.

- "【新国立競技場】冷房取りやめ、熱中症は大丈夫? 総工費1550億円 当初の観客数6万8000人". 産経ニュース (in Japanese). 28 August 2015. Retrieved 23 October 2019.

- "The Japan News". The Japan News. Archived from the original on 26 September 2015.

- 軽部, 理人; 前田, 大輔 (10 December 2019). "小学校の五輪・パラ観戦、辞退相次ぐ 熱中症を懸念". 朝日新聞 (in Japanese). Retrieved 16 December 2019.

- Tarrant, Jack (5 October 2018). "Water quality still clouding Olympic swimming venue". Reuters. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Kershaw, Tom (22 October 2018). "Tokyo 2020's worrying water quality a concerning issue that threatens to rain over Olympic parade". The Independent. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "TRIATHLON/ E. coli in water forces Tokyo to cancel swimming at Paratriathlon". The Asahi Shimbun. 18 August 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Parry, Richard Lloyd (6 September 2019). "Tokyo Olympic Games 2020 triathlon swimming course awash with sewage". The Times. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Hart, Torrey (4 February 2020). "Haley Anderson Says Tokyo Open Water Condition Concerns Have 'Gone Unheard'". Swim Swam. Retrieved 9 February 2020.

- Lord, Craig (4 December 2019). "Catherine Kase Leads USA Safety Plea For Change In Tokyo 2020 Swim Marathon Venue". Swimming World News. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- Wade, Stephen; Dampf, Andrew (4 December 2019). "Some calling on Tokyo 2020 to move open-water events due to heat and water quality". The Japan Times. Retrieved 10 December 2019.

- "Toxic threat: Tokyo 2020 organizers to take emergency measures after asbestos found at Olympics venue". RT. 30 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019.

- "Tokyo 2020 to take 'emergency measures after asbestos found' at Olympic venue". Reuters. 30 December 2019. Retrieved 31 December 2019 – via The Independent.

- "Tokyo Olympic stadium worker's death follows 190 hours of overtime in month". The Guardian. Associated Press. 11 October 2017. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- Watanabe, Kazuki (20 July 2017). "五輪・新国立競技場の工事で時間外労働212時間 新卒23歳が失踪、過労自殺". BuzzFeed Japan (in Japanese). Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "Report: Tokyo Olympics construction workers are being overworked". Free Industrial Safety & Hygiene News. 17 June 2019. Retrieved 19 September 2019.

- "South Korea complain after disputed territory appears on Tokyo 2020 map". insidethegames.biz. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- "Russia accuses Japan of politicising Tokyo 2020 Olympics and Paralympics". insidethegames.biz. Retrieved 25 August 2019.

- Dudden, Alexis (1 November 2019). "Japan's rising sun flag has a history of horror. It must be banned at the Tokyo Olympics". The Guardian. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Punk, Olie (24 March 2014). "Japan's 'Internet Nationalists' Really Hate Koreans". VICE. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Russell, Alexander (6 May 2017). "Rising Sun, Rising Nationalism". Varsity. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Withnall, Adam (11 September 2019). "South Korea asks for Japanese flag be banned at the Tokyo Olympics". The Independent. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Illmer, Andreas (3 January 2020). "Tokyo 2020: Why some people want the rising sun flag banned". BBC News. Retrieved 8 January 2020.

- Sieg, Linda (13 September 2019). "Tokyo Olympic organizers say no plans to ban 'Rising Sun' flag despite South Korean demand". Reuters. Retrieved 2 November 2019.

- Seo, Yoonjung; Wakatsuki, Yoko; Hollingsworth, Julia (7 September 2019). "'Symbol of the devil': Why South Korea wants Japan to ban the Rising Sun flag from the Tokyo Olympics". CNN.

- "Democratic Party lawmaker proposes resolution opposing Rising Sun Flag in Ntl. Assembly". The Hankyoreh. 2 October 2019.

- "China group asks IOC to ban 'rising sun' flag at Tokyo Olympics". The Mainichi. Kyodo News. 28 September 2019. Archived from the original on 1 October 2019.

- International Olympic Committee bans political protests by athletes at 2020 games BY SOPHIE LEWIS, CBS News, 9 January 2020

- Rule-50-Guidelines-Tokyo-2020.pdf

- 'Cowardice': Olympics Committee Slammed for New Guidelines Barring Athletes From Kneeling, Raising Fists by Andrea Germanos, Common Dreams, 10 January 2020

- 今, 一生 (29 September 2019). "「授業の一環」としてのオリンピック観戦、生徒の熱中症対策は十分なのか。". HARBOR BUSINESS Online (in Japanese). Retrieved 23 January 2020.