Chengdu J-7

The Chengdu J-7 (Chinese: 歼-7; third generation export version F-7; NATO reporting name: Fishcan[1]) is a People's Republic of China license-built version[2] of the Soviet Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21. Though production ceased in 2013, it continues to serve, mostly as an interceptor, in several air forces, including the People's Liberation Army Air Force.[3][4]

| J-7 / F-7 Airguard | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| An upgraded Chengdu F-7PG of the Pakistan Air Force | |

| Role | Fighter aircraft |

| Manufacturer | Chengdu Aircraft Corporation/Guizhou Aircraft Industry Corporation |

| First flight | 17 January 1966 |

| Status | Operational |

| Primary users | People's Liberation Army Air Force Pakistan Air Force Bangladesh Air Force Korean People's Air Force |

| Produced | 1965–2013 |

| Number built | 2,400+ |

| Developed from | Mikoyan-Gurevich MiG-21 |

| Developed into | Guizhou JL-9 |

Design and development

In the 1950s and early 1960s, the Soviet Union shared most of its conventional weapons technology with the People's Republic of China. The famous MiG-21, powered by a single engine and designed on a simple airframe, was inexpensive but fast, suiting the strategy of forming large groups of 'people's fighters' to overcome the technological advantages of Western aircraft. However, the Sino-Soviet split abruptly ended the initial cooperation, and from July 28 to September 1, 1960, the Soviet Union withdrew its advisers from China, resulting in the project being stopped in China.

Soviet Premier Nikita Khrushchev unexpectedly wrote to Mao Zedong in February, 1962, to inform Mao that the Soviet Union was willing to transfer MiG-21 technology to China, and he asked the Chinese to send their representatives to the Soviet Union as soon as possible to discuss the details. The Chinese viewed this offer as a Soviet gesture to make peace, and they were understandably suspicious, but they were nonetheless eager to take up the Soviet offer for an aircraft deal. A delegation headed by General Liu Yalou, the commander-in-chief of the People's Liberation Army Air Force (PLAAF) and himself a Soviet military academy graduate, was dispatched to Moscow immediately, and the Chinese delegation was given three days to visit the production facility of the MiG-21, which was previously off-limits to foreigners. The authorization for this visit was personally given by Nikita Khrushchev, and on March 30, 1962, the technology transfer deal was signed. However, given the political situation and the relationship between the two countries, the Chinese were not optimistic about gaining the technology, and thus they were prepared for reverse engineering.

Russian sources state that several complete examples of the MiG-21 were sent to China, flown by Soviet pilots, and China also received MiG-21Fs in kits, along with parts and technical documents. Just as the Chinese had expected, however, when the Soviets delivered the kits, parts and documents to Shenyang Aircraft Factory five months after the deal was signed, the Chinese discovered that the technical documents provided by the Soviets were incomplete and that some of the parts could not be used.

China set about to reverse-engineer the aircraft for local production, and in doing so, they succeeded in solving 249 major problems and reproducing eight major technical documents that were not provided by the Soviet Union. One of the major flaws was with the Hydraulics systems, which grounded up to 70% of aircraft in some squadrons until the systems were upgraded. Another major upgrade was modifications to the fuel storage to make the aircraft more stable. The MiG-21 carries most of its fuel in the forward fuselage, causing the center of gravity to shift and become unstable after about 45 minutes of operation. The J-7 has redesigned fuel tanks and significantly larger drop tanks in order to maintain a more stable center of gravity, and therefore better Longitudinal static stability. The cockpit was also revised to replace the Soviet ejection seat, which was found to be unacceptable. The forward opening canopy was replaced by a standard canopy hinged to the rear and jettisoned before the seat ejected. Otherwise, the re-engineering effort was largely successful, as the Chinese-built J-7 aircraft showed only minor differences in design and performance from the original Soviet MiG-21.[5]

In March 1964, Shenyang Aircraft Factory began the first domestic production of the J-7 jet fighter, which they successfully accomplished the next year. However, the mass production of the J-7 aircraft was severely hindered by an unexpected social and economic problem—the Cultural Revolution—that resulted in poor initial quality and slow progress, which, in turn, resulted in full-scale production only coming about in the 1980s, by which time the original aircraft design was showing its age.

In 1987 the J-7E was released, having a greatly improved wing, among other improvements. It was roughly 45% more maneuverable, and its takeoff and landing performance was greatly increased. It was also equipped with a helmet mounted sight, as well as being the first MiG-21 to be equipped with HOTAS and a multipurpose display. Many of the electronic components were British in origin, such as the gun sight and the multi purpose display. The aircraft is capable of using PL-8/Python 3 missiles with both the helmet mounted sight or the radar fire control, but the two are not connected. The pilot may use only one system at a time.[5]

In the mid 1980s Pakistan requested an aircraft with greater radar capabilities. Both the standard radar and the British Marconi radar were plagued by ground clutter, but China did not have any experience with air to ground radar at the time. In 1984 Pakistan provided assistance by having their American trained F-16 pilots provide training on proper operation of ground attack radar, which enabled the Chinese to develop the J-7M. In the late 1980s the J-7MP and J-7PG introduced significant upgrades to the radar system by converting to an Italian FIAR Grifo-7 radar. This more than tripled the effective range of the radar, as well as greatly increased the angle which the radar could detect targets.[6]

The J-7 only reached its Soviet-designed capabilities in the mid 1980s. However, the fighter is affordable and has been widely exported as the F-7, often with Western systems incorporated, like the ones sold to Pakistan. There are over 20 different export variants of the J-7, some of which are equipped to use European weaponry, such as French R.550 Magic missiles. The Discovery Channel's Wings Over The Red Star series claims that the Chinese intercepted several Soviet MiG-21s en route to North Vietnam (during the Vietnam War), but these aircraft did not perform in a manner consistent with their original specifications, suggesting that the Chinese actually intercepted down-rated aircraft that were intended for export, rather than fully capable production aircraft. For this reason, the Chinese had to re-engineer the intercepted MiG-21 airframes in order to achieve their original capabilities. China later developed the Shenyang J-8 based both on the expertise gained by the program, and by utilizing the incomplete technical information acquired from the Soviet Ye-152 developmental jet.[7][8]

In May 2013, J-7 production has ceased after decades of manufacturing. The last 12 F-7BGIs were delivered to the Bangladesh Air Force.

Operational history

Most actions carried out by the F-7 export model have been air-to-ground missions. In air-to-air missions, there have rarely been any encounters resulting in dogfights.

Africa

- Namibia

Namibian AF ordered 12 Chengdu F-7NMs in August 2005. Chinese sources reported the delivery in November 2006. This is believed to be a variation of the F-7PG acquired by Pakistan with Grifo MG radar.[9]

- Nigeria

In early 2008, Nigeria procured 12 F-7NI fighters and three FT-7NI trainers to replace the existing stock of MiG-21 aircraft. The first batch of F-7s arrived in December 2009.[10] On September 20, 2018, one pilot was killed after two Nigerian F-7Ni fighter jets crashed into Katamkpe Hill, Abuja while taking part in the rehearsals for the aerial display to mark Nigeria's 58th Independence Anniversary celebrations.[11]

- Sudan

Sudanese F-7Bs were used in the Second Sudanese Civil War against ground targets.

- Tanzania

Tanzanian Air Force F-7As served in the Uganda–Tanzania War against Uganda and Libya in 1979. Its appearance effectively brought a halt to bombing raids by Libyan Tupolev Tu-22s.

- Zimbabwe

During Zimbabwe's involvement in the DRC, six or seven F-7s were deployed to the Lubumbashi IAP and then to a similar installation near Mbuji-Mayi. From there, AFZ F-7s flew dozens of combat air patrols in the following months, attempting in vain to intercept transport aircraft used to bring supplies and troops from Rwanda and Burundi to the Congo. In late October 1998, F-7s of the No.5 Squadron were used in an offensive in east-central Congo. This began with a series of air strikes that first targeted airfields in Gbadolite, Dongo and Gmena, and then rebel and Rwandan communications and depots in the Kisangani area on November 21.[12]

Europe

- Albania

The stationing of F-7As in north of the country near the border successfully checked Yugoslav incursions into Albanian airspace.[13]

East and Southeast Asia

- China

In the mid 1990s, the PLAAF began replacing its J-7Bs with the substantially redesigned and improved J-7E variant. The wings of the J-7E have been changed to a unique "double delta" design offering improved aerodynamics and increased fuel capacity, and the J-7E also features a more powerful engine and improved avionics. The newest version of the J-7, the J-7G, entered service with the PLAAF in 2003.

The role of the J-7 in the People's Liberation Army is to provide local air defence and tactical air superiority. Large numbers are to be employed to deter enemy air operations.

- Myanmar

Myanmar purchased F-7Ms with plans to use them for interception.

Middle East

- Egypt

Relations between Egypt and Libya deteriorated after Egypt signed a peace accord with Israel. Egyptian Air Force MiG-21s shot down Libyan MiG-23s, and F-7Bs were deployed to the Egyptian-Libyan border along with MiG-21s to fend off possible further Libyan MiG-23 incursions into Egyptian airspace.

- Iran

Although not in any known combat actions, it was in several movies portraying Iranian MiG-21s during the Iran–Iraq War. One tells the story of an Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force strike on the Iraqi nuclear reactor at Osirak on September 30, 1980. Another "Attack on H3" tells the story of the 810 km-deep raids into the Iraqi heartland against Iraqi Air Force airfields on April 4, 1981, and other movies depicting the air combat in 1981 that resulted in the downing of around 70 Iraqi aircraft. However, unconfirmed reports claimed that during the later stages of the war, these aircraft were used for air-to-ground attacks. On July 24, 2007 an Iranian F-7 crashed in northern eastern Iran. The plane crashed due to technical difficulties.[14] On April 27, 2016, another Chengdu F7 crashed near Esfahan city; both pilots ejected safely.

- Iraq

F-7Bs paid for by Egypt arrived too late for the aerial combat in the early part of the Iran–Iraq War, but later participated mainly in air-to-ground sorties.

South Asia

- Bangladesh

The Bangladeshi Air Force currently operates FT-7MB Airguards, and F-7BG and F-7BGI interceptors..The 16 F-7BGIs of Bangladesh Air Force entereted service in 2013. F-7BGI are believed to be the most advanced variant and last production model of F7/J7 fighters with limited BVR capability.

- Pakistan

Pakistan is currently the largest non-Chinese F-7 operator, with ~120 F-7P and ~60 F-7PG. The Pakistan Air Force is to replace its entire fleet of F-7 with the JF-17 multirole fighter. All F-7P are planned to be retired and replaced with JF-17 Thunder aircraft by 2020.

- Sri Lanka

Sri Lanka Air Force used three F-7BS and for ground attack missions against the LTTE and three FT-7 trainers. Due to the lack of endurance and payload, SLAF sometimes uses their F-7s for pilot training purposes.[15]

Early in 2008 the air force received six more advanced F-7Gs, to use primarily as interceptors. All The F-7G's, F-7BS's and FT-7s are flown by the No 5 Jet Squadron.

Sri Lankan officials reported that on 9 September 2008, three Sri Lankan Air Force F-7s were scrambled after two rebel-flown Zlín-143 were detected by ground radar. Two were sent to bomb two rebel airstrips at Mullaitivu and Kilinochchi areas. The government reported the third intercepted one Zlin-143 resulting in one LTTE Zlín-143 shot down by the chasing F-7G using an air-to-air missile while the rebel-flown light aircraft was returning to its base at Mullaitivu after a bombing run against Vavuniya base.[16][17]

Variants

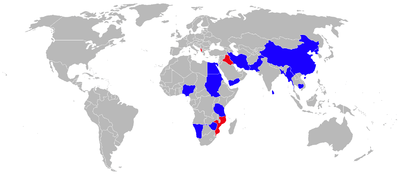

Operators

Current

- Bangladesh Air Force: 12 × F-7BG interceptors and 4 × FT-7BG two-seater fighters delivered in 2007. Additional 16 advanced F-7 BGI fighters delivered in 2012.[18] Earlier deliveries of 16 F-7MB and 8 FT-7MB trainer aircraft now retired from service.[19]

- People's Liberation Army Air Force: 290 × J-7 plus 40× J-7 trainers remained in service (As of February 2012).[20]

- People's Liberation Army Naval Air Force: 30× J-7D/E remained in service (As of February 2012).[20]

- Egyptian Air Force: 74 × F-7 in service,[21]

- Islamic Republic of Iran Air Force: 20 × F-7 in service.[22]

- Myanmar Air Force: 62 aircraft were received by the year 1990 to 1999 .24× F-7M and 6× FT-7 trainers remained in service (As of February 2012).[20]

- Namibian Air Force: 6 × F-7NM and 2 × FT-7NM in active service. A total of 12 F/FT-7NM aircraft were delivered between 2006–2008.[23]

- Nigerian Air Force: 12 × F-7 and 2 × FT-7.[24]

- North Korean Air Force: As of February 2012, 180 × F-7 remained in service. However, reports of dire levels of serviceability suggest an airworthiness rate of less than 50%.[20]

- Pakistan Air Force: As of February 2017, 139 × F-7P/PG plus 7 × FT-7 remained in service.[25]

- No. 19 Squadron Sherdils – Operated F-7P/FT-7P from 1990 [26] until April 2014.[27] Replaced by F-16A/B Block 15 ADF.[28]

- CCS Dashings – Operated F-7P from 1992 until January 2015. Replaced by JF-17 Block 1.[29]

- Sri Lankan Air Force: 9 × F-7/GS/BS and 1 × FT-7 trainer remained in service (As of February 2012).[20]

- Sudanese Air Force: 20 × F-7 in service.[30]

- Tanzanian Air Force: Originally having had 11 × F-7 in service,[31] Tanzania replaced them with 12 new J-7's (single-seat) under the designation J-7G and 2 dual-seat aircraft designated F-7TN in 2011. Originally ordered in 2009, the deliveries were completed and the aircraft are now fully operational at the air bases in Dar es Salaam and Mwanza. The new aircraft are equipped with a KLJ-6E Falcon radar, thought to be developed from the Selex Galileo Grifo 7 radar. The J-7G's primary weapon is the Chinese PL-7A short-range infrared air-to-air missile.[32]

Former

- Albanian Air Force: Total 12 F-7A in service from 1969 through 2004, now retired.[33][34][35]

- Iraqi Air Force: 80× F-7, all retired.

- Mozambican Air Force

- United States Air Force [36] (Foreign Technology Evaluation: MiG-21F-13)

- Air Force of Zimbabwe: Had 7 × F-7 in service. Now stored.[37]

Specifications (J-7MG)

Data from Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004[38]

General characteristics

- Crew: 1

- Length: 14.884 m (48 ft 10 in) (Overall)

- Wingspan: 8.32 m (27 ft 4 in)

- Height: 4.11 m (13 ft 6 in)

- Wing area: 24.88 m2 (267.8 sq ft)

- Aspect ratio: 2.8

- Airfoil: root: TsAGI S-12 (4.2%) ; tip: TsAGI S-12 (5%)[39]

- Empty weight: 5,292 kg (11,667 lb)

- Gross weight: 7,540 kg (16,623 lb) with 2x PL-2 or PL-7 air-to-air missiles

- Max takeoff weight: 9,100 kg (20,062 lb)

- Powerplant: 1 × Liyang Wopen-13F afterburning turbojet, 44.1 kN (9,900 lbf) thrust dry, 64.7 kN (14,500 lbf) with afterburner

Performance

- Maximum speed: 2,200 km/h (1,400 mph, 1,200 kn) IAS

- Maximum speed: Mach 2

- Stall speed: 210 km/h (130 mph, 110 kn) IAS

- Combat range: 850 km (530 mi, 460 nmi)

- Ferry range: 2,200 km (1,400 mi, 1,200 nmi)

- Service ceiling: 17,500 m (57,400 ft)

- Rate of climb: 195 m/s (38,400 ft/min)

Armament

- Guns: 2× 30 mm Type 30-1 cannon, 60 rounds per gun

- Hardpoints: 5 in total – 4× under-wing, 1× centreline under-fuselage with a capacity of 2,000 kg maximum (up to 500 kg each)[40],

- Rockets: 55 mm rocket pod (12 rounds), 90 mm rocket pod (7 rounds)

- Missiles: ** Air-to-air missiles: PL-2, PL-5, PL-7, PL-8, PL-9, K-13, Magic R.550, AIM-9

- Bombs: 50 kg to 500 kg unguided bombs

Avionics

- FIAR Grifo-7 mk.II radar

Accidents and incidents

- On 24 November 2015, flying officer Marium Mukhtiar – the first female fighter pilot in the Pakistan Air Force (PAF), died when a twin-seat FT-7PG crashed at PAF Base M.M. Alam near Kundian in Punjab province on a training mission. Both pilots ejected, but she succumbed to injuries received on landing. She was occupying the rear seat for Instrument Flight Rules training.[41][42]

- On 7 January 2020, Pakistan Air Force (PAF) crashed while on a routine operational training mission near Mianwali. Both pilots lost their lives in the crash.[43]

References

- Citations

- "CHINA EQUIPMENT" (PDF). Office of Naval Intelligence. United States Office of Naval Intelligence. Archived (PDF) from the original on 19 June 2018. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- J7, Sino Defence, archived from the original on 2006-07-16.

- Medeiros 2005, p. 162.

- "China's Expert Fighter Designer Knows Jets, Avoids America's Mistakes". International Relations and Security Network. Archived from the original on 2 October 2015. Retrieved 4 September 2015.

- Civil Airworthiness Certification: Former Military High-Performance Aircraft

- Civil Airworthiness Certification: Former Military High-Performance Aircraft P.2-59 to 2–62

- "Global Aircraft -- J-7 Fishbed". Archived from the original on 2016-08-06. Retrieved 2016-06-14.

- Civil Airworthiness Certification: Former Military High-Performance Aircraft By Miguel Vasconcelos, United States Department of Transportation, Federal Aviation Administration. P.2-51

- Transfers of major conventional weapons. 1950 to 2011. Archived 2014-12-16 at the Wayback Machine Stockholm International Peace Research Institute

- Jane's Defence Weekly; 21 January 2009, Vol. 46 Issue 3, p16-16

- Brown, Daniel (29 September 2018). "1 pilot killed after 2 Nigerian F-7Ni fighter jets reportedly collide in midair". Business Insider.

- "Zaire/DR Congo since 1980". Archived from the original on 11 September 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived (PDF) from the original on 2011-10-06. Retrieved 2011-04-05.CS1 maint: archived copy as title (link)

- "People's Daily Online – Iranian military plane crashes in northeastern province:report". Archived from the original on 23 May 2013. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "The MIG27 affair – Fighter Pilots reveal what the "defence analysts" forgot to tell, Sri Lanka Ministry of Defence". Archived from the original on August 25, 2007.

- "Indiandefenceforum.com". Archived from the original on 2015-10-18. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- "Daily Mirror - Sri Lanka Latest Breaking News and Headlines". www.dailymirror.lk. Archived from the original on September 15, 2008.

- Pike, John. "Bangladesh – Air Force Modernization". www.globalsecurity.org. Archived from the original on 2016-12-26. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- "Bangladesh Air Force Ordered 16 F-7BGI Fighter Aircraft". Bangladesh Defence. Archived from the original on 2017-08-07. Retrieved 2017-08-07.

- "The AMR Regional Air Force Directory 2012" (PDF). Asian Military Review. February 2012. Retrieved 12 August 2012.

- Hacket 2010, p. 250

- Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 40.

- "Namibia Arms Trade Register (1950-2017)". armstrade.sipri.org. Stockholm International Peace Research Institute. Archived from the original on 14 April 2010. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 44.

- "2017 AIR FORCES PDF | Aircraft | Aviation". Scribd.

- "PAF s' Squadrons". paffalcons.com. Archived from the original on 18 July 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Allport, Dave (28 April 2014). "First Five ex-Jordanian F-16s Delivered to Pakistan AF". airforcesdaily.com. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Chaudhry, Asif Bashir (28 April 2014). "5 used Jordanian F-16s inducted into PAF". The Nation (Pakistan). Archived from the original on 28 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- "JF-17 Thunder aircraft inducted into PAF Combat Commanders' School". The News International. 27 January 2015. Archived from the original on 27 January 2015. Retrieved 27 January 2015.

- Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 47.

- Flight International 14–20 December 2010, p. 48.

- IHS Jane's Defence Weekly, vol 50, issue 47 (Nov 20, 2013), page 21: Tanzania swaps old J-7-s for new ones

- "World Air Forces Countries". www.worldairforces.com. Archived from the original on July 16, 2012.

- "World Air Forces HOME". www.worldairforces.com. Archived from the original on February 6, 2007.

- "Chengdu F-7A/MiG-21F-13, Rinas AFB, Albania". YouTube. 31 December 1969. Archived from the original on 8 June 2015. Retrieved 4 February 2015.

- Sweetman, Bill (7 August 2012). "We didn't know what 90 percent of the switches did". aviationweek.com/blog. Archived from the original on 29 April 2014. Retrieved 29 April 2014.

- Hoyle, Craig. "World Air Forces 2018". Flightglobal. flightglobal.com. Archived from the original on 6 February 2018. Retrieved 11 April 2018.

- Jackson 2003, pp. 75–76.

- Lednicer, David. "The Incomplete Guide to Airfoil Usage". m-selig.ae.illinois.edu. Retrieved 16 April 2019.

- "Sinodefence.com". Archived from the original on September 16, 2008.

- "PAF's fighter pilot dies in plane crash". Dawn. 25 November 2015. Archived from the original on 25 May 2017. Retrieved 26 May 2017.

- Pakistan's First Female Fighter Pilot Killed in Trainer Crash, Usman Ansari, DefenseNews.com, 24 November 2015

- Siddiqui, Naveed (7 January 2020). "PAF plane on routine training mission crashes near Mianwali; 2 pilots martyred". DAWN. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Bibliography

- Gordon, Yefim and Dmitry Komissarov. Chinese Aircraft: China's Aviation Industry since 1951. Manchester, UK: Hikoki Publications, 2008. ISBN 978-1-902109-04-6.

- Hacket, James, ed. (2010), =The Military Balance 2010, International Institute for Strategic Studies

- Jackson, Paul. Jane's All The World's Aircraft 2003–2004. Coulsdon, UK: Jane's Information Group, 2003. ISBN 0-7106-2537-5.

- Medeiros, Evan S., Roger Cliff, Keith Crane and James C. Mulvenon. A New Direction for China's Defense Industry. Rand Corporation, 2005. ISBN 0-83304-079-0.

- "World Air Forces". Flight International, 14–20 December 2010. pp. 26–53.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chengdu J-7. |