Chalcopyrite

Chalcopyrite ( /ˌkælkəˈpaɪraɪt, -koʊ-/[7][8] KAL-ko-PY-ryt) is a copper iron sulfide mineral that crystallizes in the tetragonal system. It has the chemical formula CuFeS2. It has a brassy to golden yellow color and a hardness of 3.5 to 4 on the Mohs scale. Its streak is diagnostic as green tinged black.

| Chalcopyrite | |

|---|---|

| |

| General | |

| Category | Sulfide mineral |

| Formula (repeating unit) | CuFeS2 |

| Strunz classification | 2.CB.10a |

| Crystal system | Tetragonal |

| Crystal class | Scalenohedral (42m) H-M symbol: (4 2m) |

| Space group | I42d |

| Unit cell | a = 5.289 Å, c = 10.423 Å; Z = 4 |

| Identification | |

| Formula mass | 183.54 g/mol |

| Color | Brass yellow, may have iridescent purplish tarnish. |

| Crystal habit | Predominantly the disphenoid and resembles a tetrahedron, commonly massive, and sometimes botryoidal. |

| Twinning | Penetration twins |

| Cleavage | Indistinct on {011} |

| Fracture | Irregular to uneven |

| Tenacity | Brittle |

| Mohs scale hardness | 3.5 |

| Luster | Metallic |

| Streak | Greenish black |

| Diaphaneity | Opaque |

| Specific gravity | 4.1 – 4.3 |

| Optical properties | Opaque |

| Solubility | Soluble in HNO3 |

| Other characteristics | magnetic on heating |

| References | [2][3][4][5][6] |

On exposure to air, chalcopyrite tarnishes to a variety of oxides, hydroxides, and sulfates. Associated copper minerals include the sulfides bornite (Cu5FeS4), chalcocite (Cu2S), covellite (CuS), digenite (Cu9S5); carbonates such as malachite and azurite, and rarely oxides such as cuprite (Cu2O). Is rarely found in association with native copper. Chalcopyrite is a conductor of electricity.

Etymology

The name chalcopyrite comes from the Greek words chalkos, which means copper, and pyrites', which means striking fire.[9] It was sometimes historically referred to as "yellow copper".[10]

Identification

Chalcopyrite is often confused with pyrite and gold since all three of these minerals have a yellowish color and a metallic luster. Some important mineral characteristics that help distinguish these minerals are hardness and streak. Chalcopyrite is much softer than pyrite and can be scratched with a knife, whereas pyrite cannot be scratched by a knife.[11] However, chalcopyrite is harder than gold, which, if pure, can be scratched by copper.[12] Chalcopyrite has a distinctive black streak with green flecks in it. Pyrite has a black streak and gold has a yellow streak.[13]

Chemistry

Natural chalcopyrite has no solid solution series with any other sulfide minerals. There is limited substitution of Zn with Cu despite chalcopyrite having the same crystal structure as sphalerite.

Minor amounts of elements such as Ag, Au, Cd, Co, Ni, Pb, Sn, and Zn can be measured (at part per million levels), likely substituting for Cu and Fe. Selenium, Bi, Te, and As may substitute for sulfur in minor amounts.[14] Chalcopyrite can be oxidized to form malachite, azurite, and cuprite.[15]

Paragenesis

Chalcopyrite is present with many ore-bearing environments via a variety of ore forming processes.

Chalcopyrite is present in volcanogenic massive sulfide ore deposits and sedimentary exhalative deposits, formed by deposition of copper during hydrothermal circulation. Chalcopyrite is concentrated in this environment via fluid transport.

Porphyry copper ore deposits are formed by concentration of copper within a granite stock during the ascent and crystallisation of a magma. Chalcopyrite in this environment is produced by concentration within a magmatic system.

Chalcopyrite is an accessory mineral in Kambalda type komatiitic nickel ore deposits, formed from an immiscible sulfide liquid in sulfide-saturated ultramafic lavas. In this environment chalcopyrite is formed by a sulfide liquid stripping copper from an immiscible silicate liquid.

Occurrence

Even though Chalcopyrite does not contain the most copper in its structure relative to other minerals, it is the most important copper ore since it can be found in many localities. Chalcopyrite ore occurs in a variety of ore types, from huge masses as at Timmins, Ontario, to irregular veins and disseminations associated with granitic to dioritic intrusives as in the porphyry copper deposits of Broken Hill, the American cordillera and the Andes. The largest deposit of nearly pure chalcopyrite ever discovered in Canada was at the southern end of the Temagami Greenstone Belt where Copperfields Mine extracted the high-grade copper.[16]

Chalcopyrite is present in the supergiant Olympic Dam Cu-Au-U deposit in South Australia.

Chalcopyrite may also be found in coal seams associated with pyrite nodules, and as disseminations in carbonate sedimentary rocks.

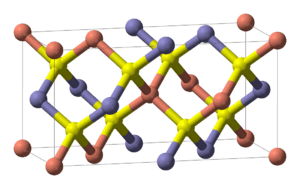

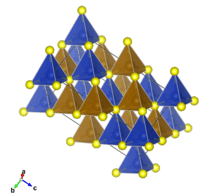

Structure

Chalcopyrite is a member of the tetragonal crystal system. Crystallographically the structure of chalcopyrite is closely related to that of zinc blende ZnS (sphalerite). The unit cell is twice as large, reflecting an alternation of Cu+ and Fe3+ ions replacing Zn2+ ions in adjacent cells. In contrast to the pyrite structure chalcopyrite has single S2− sulfide anions rather than disulfide pairs. Another difference is that the iron cation is not diamagnetic low spin Fe(II) as in pyrite.

In the crystal structure, each metal ion is tetrahedrally coordinated to 4 sulfur anions. Each sulfur anion is bonded to two copper atoms and two iron atoms.

Extraction of copper

Copper metal can be extracted from the open air roasting of a mixture of chalcopyrite and silica sand, as shown in the following reaction:

- 2CuFeS

2 (s) + 5O

2 (g) + 2SiO

2 (s) ⇌ 2Cu (l) + 4SO

2 (g) + 2FeSiO

3 (l)

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Chalcopyrite. |

| Look up chalcopyrite in Wiktionary, the free dictionary. |

Although if roasted partially it produces Cu

2S and FeO.

See also

- Classification of minerals

- List of minerals

- Kesterite

References

- "VESTA". jp-minerals.org. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Klein, Cornelis and Cornelius S. Hurlbut, Jr., Manual of Mineralogy, Wiley, 20th ed., 1985, pp. 277 – 278 ISBN 0-471-80580-7

- Palache, C., H. Berman, and C. Frondel (1944) Dana’s system of mineralogy, (7th edition), v. I, 219–224

- Chalcopyrite on Mindat.org

- Chalcopyrite data on Webmineral.com

- Chalcopyrite in the Handbook of Mineralogy

- "Chalcopyrite". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Chalcopyrite". Merriam-Webster Dictionary. Retrieved 2016-01-21.

- "Chalcopyrite". www.esci.umn.edu. Minerals. University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Museum, United States National (1885). Bulletin. U.S. Government Printing Office.

- "Mohs Hardness Test". www.oakton.edu. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Hardness". Earth's Minerals. learnbps.bismarckschools.org. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- "Fool's gold and real gold – How to tell the difference". geology.com. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Dare, Sarah A.S.; Barnes, Sarah-Jane; Prichard, Hazel M.; Fisher, Peter C. (2 March 2011). "Chalcophile and platinum-group element (PGE) concentrations in the sulfide minerals from the McCreedy East deposit, Sudbury, Canada, and the origin of PGE in pyrite". Mineralium Deposita. 46 (4): 381–407. doi:10.1007/s00126-011-0336-9.

- "Chalcopyrite". www.esci.umn.edu. Minerals. University of Minnesota. Retrieved 2019-12-20.

- Barnes, Michael (2008). More than Free Gold. Renfrew, Ontario: General Store Publishing House. p. 31. ISBN 978-1-897113-90-5. Retrieved 2015-08-02.

- "VESTA". jp-minerals.org. Retrieved 20 December 2019.