Granite

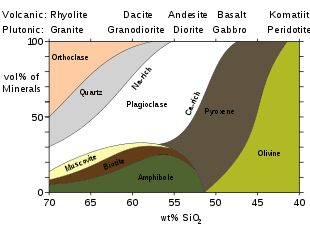

Granite ( /ˈɡrænɪt/) is a common type of felsic intrusive igneous rock that is granular and phaneritic in texture. Granites can be predominantly white, pink, or gray in color, depending on their mineralogy. The word "granite" comes from the Latin granum, a grain, in reference to the coarse-grained structure of such a completely crystalline rock. Strictly speaking, granite is an igneous rock with between 20% and 60% quartz by volume, and at least 35% of the total feldspar consisting of alkali feldspar, although commonly the term "granite" is used to refer to a wider range of coarse-grained igneous rocks containing quartz and feldspar.

| Igneous rock | |

| Composition | |

|---|---|

| Potassium feldspar, plagioclase feldspar, and quartz; differing amounts of muscovite, biotite, and hornblende-type amphiboles |

The term "granitic" means granite-like and is applied to granite and a group of intrusive igneous rocks with similar textures and slight variations in composition and origin. These rocks mainly consist of feldspar, quartz, mica, and amphibole minerals, which form an interlocking, somewhat equigranular matrix of feldspar and quartz with scattered darker biotite mica and amphibole (often hornblende) peppering the lighter color minerals. Occasionally some individual crystals (phenocrysts) are larger than the groundmass, in which case the texture is known as porphyritic. A granitic rock with a porphyritic texture is known as a granite porphyry. Granitoid is a general, descriptive field term for lighter-colored, coarse-grained igneous rocks. Petrographic examination is required for identification of specific types of granitoids.[1] The extrusive igneous rock equivalent of granite is rhyolite.[2]

Granite is nearly always massive (i.e., lacking any internal structures), hard, and tough. These properties have made granite a widespread construction stone throughout human history. The average density of granite is between 2.65 and 2.75 g/cm3 (165 and 172 lb/cu ft),[3] its compressive strength usually lies above 200 MPa, and its viscosity near STP is 3–6·1019 Pa·s.[4]

The melting temperature of dry granite at ambient pressure is 1215–1260 °C (2219–2300 °F);[5] it is strongly reduced in the presence of water, down to 650 °C at a few kBar pressure.[6]

Granite has poor primary permeability overall, but strong secondary permeability through cracks and fractures if they are present.

Mineralogy

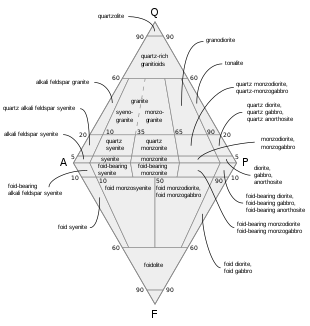

Granite is classified according to the QAPF diagram for coarse grained plutonic rocks and is named according to the percentage of quartz, alkali feldspar (orthoclase, sanidine, or microcline) and plagioclase feldspar on the A-Q-P half of the diagram. True granite (according to modern petrologic convention) contains both plagioclase and alkali feldspars. When a granitoid is devoid or nearly devoid of plagioclase, the rock is referred to as alkali feldspar granite. When a granitoid contains less than 10% orthoclase, it is called tonalite; pyroxene and amphibole are common in tonalite. A granite containing both muscovite and biotite micas is called a binary or two-mica granite. Two-mica granites are typically high in potassium and low in plagioclase, and are usually S-type granites or A-type granites.

Occurrence

Granite containing rock is widely distributed throughout the continental crust.[8] Much of it was intruded during the Precambrian age; it is the most abundant basement rock that underlies the relatively thin sedimentary veneer of the continents. Outcrops of granite tend to form tors, domes or bornhardts, and rounded massifs. Granites sometimes occur in circular depressions surrounded by a range of hills, formed by the metamorphic aureole or hornfels. Granite often occurs as relatively small, less than 100 km2 stock masses (stocks) and in batholiths that are often associated with orogenic mountain ranges. Small dikes of granitic composition called aplites are often associated with the margins of granitic intrusions. In some locations, very coarse-grained pegmatite masses occur with granite.

Origin

Granite has a felsic composition and is more common in continental crust than in oceanic crust. They are crystallized from felsic melts which are less dense than mafic rocks and thus tend to ascend toward the surface. In contrast, mafic rocks, either basalts or gabbros, once metamorphosed at eclogite facies, tend to sink into the mantle beneath the Moho.

Petrogenetic mechanism

Granitoids have crystallized from felsic magmas that have compositions at or near a eutectic point (or a temperature minimum on a cotectic curve). Magmas are composed of melts and minerals in variable abundances. Traditionally, magmatic minerals are crystallized from the melts that have completely separated from their parental rocks and thus are highly evolved because of igneous differentiation. If a granite has a slowly cooling process, it has the potential to form larger crystals.

There are also peritectic and residual minerals in granitic magmas. Peritectic minerals are generated through peritectic reactions, whereas residual minerals are inherited from parental rocks. In either case, magmas will evolve to the eutectic for crystallization upon cooling. Anatectic melts are also produced by peritectic reactions, but they are much less evolved than magmatic melts because they have not separated from their parental rocks. Nevertheless, the composition of anatectic melts may change toward the magmatic melts through high-degree fractional crystallization.

Fractional crystallisation serves to reduce a melt in iron, magnesium, titanium, calcium and sodium, and enrich the melt in potassium and silicon – alkali feldspar (rich in potassium) and quartz (SiO2), are two of the defining constituents of granite. This process operates regardless of the origin of parental magmas to granites, and regardless of their chemistry.

Alphabet classification system

The composition and origin of any magma that differentiates into granite leave certain petrological evidence as to what the granite's parental rock was. The final texture and composition of a granite are generally distinctive as to its parental rock. For instance, a granite that is derived from partial melting of metasedimentary rocks may have more alkali feldspar, whereas a granite derived from partial melting of metaigneous rocks may be richer in plagioclase. It is on this basis that the modern "alphabet" classification schemes are based.

The letter-based Chappell & White classification system was proposed initially to divide granites into I-type (igneous source) granite and S-type (sedimentary sources).[9] Both types are produced by partial melting of crustal rocks, either metaigneous rocks or metasedimentary rocks.

M-type granite was later proposed to cover those granites that were clearly sourced from crystallized mafic magmas, generally sourced from the mantle. However, this proposal has been rejected by studies of experimental petrology, which demonstrate that partial melting of mantle peridotite cannot produce granitic melts in any case. Although the fractional crystallisation of basaltic melts can yield small amounts of granites, such granites must occur together with large amounts of basaltic rocks.

A-type granites were defined as to occur in anorogenic setting, have alkaline and anhydrous compositions. They show a peculiar mineralogy and geochemistry, with particularly high silicon and potassium at the expense of calcium and magnesium.[10] These granites are produced by partial melting of refractory lithology such as granulites in the lower continental crust at high thermal gradients. This leads to significant extraction of hydrous felsic melts from granulite-facies resitites. A-type granites occur in the Koettlitz Glacier Alkaline Province in the Royal Society Range, Antarctica. The rhyolites of the Yellowstone Caldera are examples of volcanic equivalents of A-type granite.

H-type granites were suggested for hybrid granites, which were hypothesized to form by mixing between mafic and felsic from different sources, e.g. M-type and S-type. However, the big difference in rheology between mafic and felsic magmas makes this process hardly happening in nature.

Granitization

An old, and largely discounted process, granitization states that granite is formed in place through extreme metasomatism by fluids bringing in elements, e.g. potassium, and removing others, e.g. calcium, to transform a metamorphic rock into a granite. This was supposed to occur across a migrating front.

After more than 50 years of studies, it becomes clear that granitic magmas have separated from their sources and experienced fractional crystallization during their ascent toward the surface. On the other hand, granitic melts can be produced in place through the partial melting of metamorphic rocks by extracting melt-mobile elements such as potassium and silicon into the melts but leaving others such as calcium and iron in granulite residues. Once a metamorphic rock is melted, it becomes a kind of migmatites which are composed of leucosome and melanosome.

In nature, metamorphic rocks may undergo partial melting to transform into migmatites through peritectic reactions, with anatectic melts to crystallize as leucosomes. As soon as the anatectic melts have separated from their sources and highly evolved through fractional crystallization during their ascent toward the surface, they become the magmatic melts and minerals of granitic composition.

After the extraction of anatectic melts, the migmatites become a kind of granulites. In all cases, the partial melting of solid rocks requires high temperatures, and also water or other volatiles which act as a catalyst by lowering the solidus temperature of these rocks. The production of granite at crustal depths requires high heat flow, which cannot be provided by heat production elements in the crust. Furthermore, high heat flow is necessary to produce granulite facies metamorphic rocks in orogens, indicating extreme metamorphism at high thermal gradients. In-situ granitisation by the extreme metamorphism is possible if crustal rocks would be heated by the asthenospheric mantle in rifting orogens, where collision-thickened orogenic lithosphere is thinned at first and then underwent extensional tectonism for active rifting.[11]

Ascent and emplacement

The ascent and emplacement of large volumes of granite within the upper continental crust is a source of much debate amongst geologists. There is a lack of field evidence for any proposed mechanisms, so hypotheses are predominantly based upon experimental data. There are two major hypotheses for the ascent of magma through the crust:

- Stokes diapir

- Fracture propagation

Of these two mechanisms, Stokes diapir was favoured for many years in the absence of a reasonable alternative. The basic idea is that magma will rise through the crust as a single mass through buoyancy. As it rises, it heats the wall rocks, causing them to behave as a power-law fluid and thus flow around the pluton allowing it to pass rapidly and without major heat loss.[12] This is entirely feasible in the warm, ductile lower crust where rocks are easily deformed, but runs into problems in the upper crust which is far colder and more brittle. Rocks there do not deform so easily: for magma to rise as a pluton it would expend far too much energy in heating wall rocks, thus cooling and solidifying before reaching higher levels within the crust.

Fracture propagation is the mechanism preferred by many geologists as it largely eliminates the major problems of moving a huge mass of magma through cold brittle crust. Magma rises instead in small channels along self-propagating dykes which form along new or pre-existing fracture or fault systems and networks of active shear zones.[13] As these narrow conduits open, the first magma to enter solidifies and provides a form of insulation for later magma.

Granitic magma must make room for itself or be intruded into other rocks in order to form an intrusion, and several mechanisms have been proposed to explain how large batholiths have been emplaced:

- Stoping, where the granite cracks the wall rocks and pushes upwards as it removes blocks of the overlying crust

- Assimilation, where the granite melts its way up into the crust and removes overlying material in this way

- Inflation, where the granite body inflates under pressure and is injected into position

Most geologists today accept that a combination of these phenomena can be used to explain granite intrusions, and that not all granites can be explained entirely by one or another mechanism.

Weathering

Physical weathering occurs on a large scale in the form of exfoliation joints, which are the result of granite's expanding and fracturing as pressure is relieved when overlying material is removed by erosion or other processes.

Chemical weathering of granite occurs when dilute carbonic acid, and other acids present in rain and soil waters, alter feldspar in a process called hydrolysis.[14][15] As demonstrated in the following reaction, this causes potassium feldspar to form kaolinite, with potassium ions, bicarbonate, and silica in solution as byproducts. An end product of granite weathering is grus, which is often made up of coarse-grained fragments of disintegrated granite.

- 2 KAlSi3O8 + 2 H2CO3 + 9 H2O → Al2Si2O5(OH)4 + 4 H4SiO4 + 2 K+ + 2 HCO3−

Climatic variations also influence the weathering rate of granites. For about two thousand years, the relief engravings on Cleopatra's Needle obelisk had survived the arid conditions of its origin before its transfer to London. Within two hundred years, the red granite has drastically deteriorated in the damp and polluted air there.[16]

Soil development on granite reflects the rock's high quartz content and dearth of available bases, with the base-poor status predisposing the soil to acidification and podzolization in cool humid climates as the weather-resistant quartz yields much sand.[17] Feldspars also weather slowly in cool climes, allowing sand to dominate the fine-earth fraction. In warm humid regions, the weathering of feldspar as described above is accelerated so as to allow a much higher proportion of clay with the Cecil soil series a prime example of the consequent Ultisol great soil group.[18]

Natural radiation

Granite is a natural source of radiation, like most natural stones.

Potassium-40 is a radioactive isotope of weak emission, and a constituent of alkali feldspar, which in turn is a common component of granitic rocks, more abundant in alkali feldspar granite and syenites.

Some granites contain around 10 to 20 parts per million (ppm) of uranium. By contrast, more mafic rocks, such as tonalite, gabbro and diorite, have 1 to 5 ppm uranium, and limestones and sedimentary rocks usually have equally low amounts. Many large granite plutons are sources for palaeochannel-hosted or roll front uranium ore deposits, where the uranium washes into the sediments from the granite uplands and associated, often highly radioactive pegmatites. Cellars and basements built into soils over granite can become a trap for radon gas, which is formed by the decay of uranium.[19] Radon gas poses significant health concerns and is the number two cause of lung cancer in the US behind smoking.[20]

Thorium occurs in all granites.[21] Conway granite has been noted for its relatively high thorium concentration of 56±6 ppm.[22]

There is some concern that some granite sold as countertops or building material may be hazardous to health.[23] Dan Steck of St. Johns University has stated[24] that approximately 5% of all granite is of concern, with the caveat that only a tiny percentage of the tens of thousands of granite slab types have been tested. Various resources from national geological survey organizations are accessible online to assist in assessing the risk factors in granite country and design rules relating, in particular, to preventing accumulation of radon gas in enclosed basements and dwellings.

A study of granite countertops was done (initiated and paid for by the Marble Institute of America) in November 2008 by National Health and Engineering Inc. of USA. In this test, all of the 39 full-size granite slabs that were measured for the study showed radiation levels well below the European Union safety standards (section 4.1.1.1 of the National Health and Engineering study) and radon emission levels well below the average outdoor radon concentrations in the US.[25]

Industry

Granite and related marble industries are considered one of the oldest industries in the world, existing as far back as Ancient Egypt.[26]

Major modern exporters of granite include China, India, Italy, Brazil, Canada, Germany, Sweden, Spain and the United States.[27]

Uses

Antiquity

_inscriptions.jpg)

The Red Pyramid of Egypt (circa 2590 BC), named for the light crimson hue of its exposed limestone surfaces, is the third largest of Egyptian pyramids. Pyramid of Menkaure, likely dating 2510 BC, was constructed of limestone and granite blocks. The Great Pyramid of Giza (c. 2580 BC) contains a huge granite sarcophagus fashioned of "Red Aswan Granite". The mostly ruined Black Pyramid dating from the reign of Amenemhat III once had a polished granite pyramidion or capstone, which is now on display in the main hall of the Egyptian Museum in Cairo (see Dahshur). Other uses in Ancient Egypt include columns, door lintels, sills, jambs, and wall and floor veneer.[28] How the Egyptians worked the solid granite is still a matter of debate. Patrick Hunt[29] has postulated that the Egyptians used emery, which has greater hardness on the Mohs scale.

Rajaraja Chola I of the Chola Dynasty in South India built the world's first temple entirely of granite in the 11th century AD in Tanjore, India. The Brihadeeswarar Temple dedicated to Lord Shiva was built in 1010. The massive Gopuram (ornate, upper section of shrine) is believed to have a mass of around 81 tonnes. It was the tallest temple in south India.[30]

Imperial Roman granite was quarried mainly in Egypt, and also in Turkey, and on the islands of Elba and Giglio. Granite became "an integral part of the Roman language of monumental architecture".[31] The quarrying ceased around the third century AD. Beginning in Late Antiquity the granite was reused, which since at least the early 16th century became known as spolia. Through the process of case-hardening, granite becomes harder with age. The technology required to make tempered steel chisels was largely forgotten during the Middle Ages. As a result, Medieval stoneworkers were forced to use saws or emery to shorten ancient columns or hack them into discs. Giorgio Vasari noted in the 16th century that granite in quarries was "far softer and easier to work than after it has lain exposed" while ancient columns, because of their "hardness and solidity have nothing to fear from fire or sword, and time itself, that drives everything to ruin, not only has not destroyed them but has not even altered their colour."[31]

Modern

Sculpture and memorials

In some areas, granite is used for gravestones and memorials. Granite is a hard stone and requires skill to carve by hand. Until the early 18th century, in the Western world, granite could be carved only by hand tools with generally poor results.

A key breakthrough was the invention of steam-powered cutting and dressing tools by Alexander MacDonald of Aberdeen, inspired by seeing ancient Egyptian granite carvings. In 1832, the first polished tombstone of Aberdeen granite to be erected in an English cemetery was installed at Kensal Green Cemetery. It caused a sensation in the London monumental trade and for some years all polished granite ordered came from MacDonald's.[32] As a result of the work of sculptor William Leslie, and later Sidney Field, granite memorials became a major status symbol in Victorian Britain. The royal sarcophagus at Frogmore was probably the pinnacle of its work, and at 30 tons one of the largest. It was not until the 1880s that rival machinery and works could compete with the MacDonald works.

Modern methods of carving include using computer-controlled rotary bits and sandblasting over a rubber stencil. Leaving the letters, numbers, and emblems exposed on the stone, the blaster can create virtually any kind of artwork or epitaph.

The stone known as "black granite" is usually gabbro, which has a completely different chemical composition.[33]

Buildings

Granite has been extensively used as a dimension stone and as flooring tiles in public and commercial buildings and monuments. Aberdeen in Scotland, which is constructed principally from local granite, is known as "The Granite City". Because of its abundance in New England, granite was commonly used to build foundations for homes there. The Granite Railway, America's first railroad, was built to haul granite from the quarries in Quincy, Massachusetts, to the Neponset River in the 1820s.

Engineering

Engineers have traditionally used polished granite surface plates to establish a plane of reference, since they are relatively impervious, inflexible, and maintain good dimensional stability. Sandblasted concrete with a heavy aggregate content has an appearance similar to rough granite, and is often used as a substitute when use of real granite is impractical. Granite tables are used extensively as bases or even as the entire structural body of optical instruments, CMMs, and very high precision CNC machines because of granite's rigidity, high dimensional stability, and excellent vibration characteristics. A most unusual use of granite was as the material of the tracks of the Haytor Granite Tramway, Devon, England, in 1820. Granite block is usually processed into slabs, which can be cut and shaped by a cutting center. In military engineering, Finland planted granite boulders along its Mannerheim Line to block invasion by Russian tanks in the winter war of 1940.

Other uses

Curling stones are traditionally fashioned of Ailsa Craig granite. The first stones were made in the 1750s, the original source being Ailsa Craig in Scotland. Because of the rarity of this granite, the best stones can cost as much as US$1,500. Between 60 and 70 percent of the stones used today are made from Ailsa Craig granite, although the island is now a wildlife reserve and is still used for quarrying under license for Ailsa granite by Kays of Scotland for curling stones.[34]

Rock climbing

Granite is one of the rocks most prized by climbers, for its steepness, soundness, crack systems, and friction. Well-known venues for granite climbing include the Yosemite Valley, the Bugaboos, the Mont Blanc massif (and peaks such as the Aiguille du Dru, the Mourne Mountains, the Adamello-Presanella Alps, the Aiguille du Midi and the Grandes Jorasses), the Bregaglia, Corsica, parts of the Karakoram (especially the Trango Towers), the Fitzroy Massif, Patagonia, Baffin Island, Ogawayama, the Cornish coast, the Cairngorms, Sugarloaf Mountain in Rio de Janeiro, Brazil, and the Stawamus Chief, British Columbia, Canada.

Granite rock climbing is so popular that many of the artificial rock climbing walls found in gyms and theme parks are made to look and feel like granite.

Granite was used for setts on the St. Louis riverfront and for the piers of the Eads Bridge (background)

Granite was used for setts on the St. Louis riverfront and for the piers of the Eads Bridge (background).jpg)

Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, a classic granitic dome and popular rock climbing destination

Half Dome, Yosemite National Park, a classic granitic dome and popular rock climbing destination Rixö red granite quarry in Lysekil, Sweden

Rixö red granite quarry in Lysekil, Sweden

See also

- Cheyenne Mountain Complex

- Epoxy granite

- Exfoliating granite – Granite skin peeling like an onion (desquamation) because of weathering

- Falkenfelsen, also known as Falcon Rock

- Fall River granite – A Precambrian bedrock underlying the City of Fall River, Massachusetts and surrounding area

- Greisen – A highly altered granitic rock or pegmatite

- Hypersolvus

- Kashmir gold – A type of granite found in Madurai, Tamil Nadu state, India

- List of rock types – A list of rock types recognized by geologists

- Luxullianite – A rare type of granite

- Mourne Mountains – Mountain range in Northern Ireland

- Orbicular granite

- Pikes Peak granite, Colorado

- Quartz monzonite

- Rapakivi granite – A hornblende-biotite granite containing large round crystals of orthoclase each with a rim of oligoclase

- Stone Mountain – Mountain and state park in Georgia, United States, Georgia

- Subsolvus

- Wicklow Mountains – Mountain range in Ireland, Ireland

References

- Notes

- "Granitoids – Granite and the Related Rocks Granodiorite, Diorite and Tonalite". Geology.about.com. 2010-02-06. Retrieved 2010-05-09.

- Haldar, S.K.; Tišljar, J. (2014). Introduction to Mineralogy and Petrology. Elsevier. p. 116. ISBN 978-0-12-408133-8.

- "Rock Types and Specific Gravities". EduMine. Archived from the original on 2017-08-31. Retrieved 2017-08-27.

- Kumagai, Naoichi; Sadao Sasajima; Hidebumi Ito (1978). "Long-term Creep of Rocks: Results with Large Specimens Obtained in about 20 Years and Those with Small Specimens in about 3 Years". Journal of the Society of Materials Science (Japan). 27 (293): 157–161. doi:10.2472/jsms.27.155.

- Larsen, Esper S. (1929). "The temperatures of magmas". American Mineralogist. 14: 81–94.

- Holland, Tim; Powell, Roger (2001). "Calculation of phase relations involving haplogranitic melts using an internally consistent thermodynamic dataset". Journal of Petrology. 42 (4): 673–683. Bibcode:2001JPet...42..673H. doi:10.1093/petrology/42.4.673.

- Harvey Blatt & Robert J. Tracy (1997). Petrology (2nd ed.). New York: Freeman. p. 66. ISBN 0-7167-2438-3.

- Singh, G. (2009). Earth Science Today. Discovery Publishing House. ISBN 9788183564380.

- Chappell, B. W.; White, A. J. R. (2001). "Two contrasting granite types: 25 years later". Australian Journal of Earth Sciences. 48 (4): 489–499. Bibcode:2001AuJES..48..489C. doi:10.1046/j.1440-0952.2001.00882.x.

- Winter, J.D. (2010) Principles of Igneous and Metamorphic Petrology. 2nd Edition, page 381.

- Zheng, Y.-F.; Chen, R.-X. (2017). "Regional metamorphism at extreme conditions: Implications for orogeny at convergent plate margins". Journal of Asian Earth Sciences. 145: 46–73. Bibcode:2017JAESc.145...46Z. doi:10.1016/j.jseaes.2017.03.009.

- Weinberg, R. F.; Podladchikov, Y. (1994). "Diapiric ascent of magmas through power law crust and mantle". Journal of Geophysical Research. 99 (B5): 9543. Bibcode:1994JGR....99.9543W. doi:10.1029/93JB03461. S2CID 19470906.

- Clemens, John (1998). "Observations on the origins and ascent mechanisms of granitic magmas". Journal of the Geological Society of London. 155 (Part 5): 843–51. Bibcode:1998JGSoc.155..843C. doi:10.1144/gsjgs.155.5.0843.

- "Granite [Weathering]". University College London. Archived from the original on 15 October 2014. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- "Hydrolysis". Geological Society of London. Retrieved 10 July 2014.

- Marsh, William M.; Kaufman, Martin M. (2012). Physical Geography: Great Systems and Global Environments. Cambridge University Press. p. 510. ISBN 9781107376649.

- http://luitool.soilweb.ca/podzols/Land Use Impacts on Soil Quality

- https://www.soils4teachers.org/files/s4t/k12outreach/nc-state-soil-booklet.pdf Cecil -- North Carolina State Soil

- "Decay series of Uranium". Archived from the original on March 9, 2012. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- "Radon and Cancer: Questions and Answers". National Cancer Institute. Retrieved 2008-10-19.

- Hubbert, M. King (March 8, 1956) Nuclear Energy and the Fossil Fuels. American Petroleum Institute Conference. Energy Bulletin.

- Adams, J. A.; Kline, M. C.; Richardson, K. A.; Rogers, J. J. (1962). "The Conway Granite of New Hampshire As a Major Low-Grade Thorium Resource". Proceedings of the National Academy of Sciences of the United States of America. 48 (11): 1898–905. Bibcode:1962PNAS...48.1898A. doi:10.1073/pnas.48.11.1898. PMC 221093. PMID 16591014.

- "Granite Countertops and Radiation". United States Environmental Protection Agency. 4 May 2015. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Steck, Daniel J. (2009). "Pre- and Post-Market Measurements of Gamma Radiation and Radon Emanation from a Large Sample of Decorative Granites" (PDF). Nineteenth International Radon Symposium. pp. 28–51.

- Natural Stone Countertops and Radon – Environmental Health and Engineering – Assessing Exposure to Radon and Radiation from Granite Countertops.

- Nelson L. Nemerow (27 January 2009). Environmental Engineering: Environmental Health and Safety for Municipal Infrastructure, Land Use and Planning, and Industry. John Wiley & Sons. p. 40. ISBN 978-0-470-08305-5.

- Parmodh Alexander (15 January 2009). A Handbook of Minerals, Crystals, Rocks and Ores. New India Publishing. p. 585. ISBN 978-81-907237-8-7.

- James A. Harrell. "Decorative Stones in the Pre-Ottoman Islamic Buildings of Cairo, Egypt". Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- "Egyptian Genius: Stoneworking for Eternity". Archived from the original on 2007-10-14. Retrieved 2008-01-06.

- Heitzman, James (1991). "Ritual Polity and Economy: The Transactional Network of an Imperial Temple in Medieval South India". Journal of the Economic and Social History of the Orient. BRILL. 34 (1/2): 23–54. doi:10.1163/156852091x00157. JSTOR 3632277.

- Waters, Michael (2016). "Reviving Antiquity with Granite: Spolia and the Development of Roman Renaissance Architecture". Architectural History. 59: 149–179. doi:10.1017/arh.2016.5.

- Friends of West Norwood Cemetery newsletter 71 Alexander MacDonald (1794–1860) – Stonemason,

- "Black granite and black marble". Trade Brochure. Graniteland.com. Retrieved 21 May 2014.

- Roach, John (October 27, 2004). "National Geographic News — Puffins Return to Scottish Island Famous for Curling Stones". National Geographic News.

Further reading

- Blasik, Miroslava; Hanika, Bogdashka, eds. (2012). Granite: Occurrence, Mineralogy and Origin. Hauppauge, New York: Nova Science. ISBN 978-1-62081-566-3.

- Twidale, Charles Rowland (2005). Landforms and Geology of Granite Terrains. Leiden, Netherlands: A. A. Balkema. ISBN 978-0-415-36435-5.

- Marmo, Vladimir (1971). Granite Petrology and the Granite Problem. Amsterdam, Netherlands: Elsevier Scientific. ISBN 978-0-444-40852-5.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Granite. |