Calogerà family

The Calogerà family (Greek: Καλογερά (Kalogera or Kaloghera, from Kalogeros), Croatian: Kalogjera and Kalođera) are an ancient Byzantine-, and later Greco-Venetian, gens that has produced many important individuals in the history of Europe and Brazil. With origins in Cyprus and Byzantium, the family achieved levels of wealth, prominence, and aristocracy over the centuries in branches found across modern Greece, Italy, Croatia, Serbia, Albania, Romania, France, and Brazil.[1][2] The Calogerà are studied in numerous registers of nobility, including the Libro d'Oro of Corfu, Wappenbuch des Königreichs Dalmatien (1873),[3] Livre d'Or de la Noblesse Ionienne (1925), and Heraldika Shqiptare (2000), among others. Members and descendants of this family continue to serve important roles in their respective countries to this day.

| Calogerà Kalogjera, Calógeras | |

|---|---|

| Mediterranean aristocratic family | |

The coats of arms of the Calogerà family often depict an Eastern Orthodox monk or priest. | |

| Country | Byzantine Empire Republic of Venice Septinsular Republic Austrian Empire Greece Italy Croatia Brazil |

| Etymology | The surname derives from a mediæval Greek title for an Eastern monk, kalogēros (καλόγηρος), meaning "venerable" (lit., "good elder"), in recognition of this family's association with monasticism and priesthood as early as the Byzantine period. |

| Founded | 5th century |

| Members | Marko, Bishop of Split João Pandiá Calógeras Nikica Kalogjera Angelo Calogerà Ioannis Kalogeras |

| Connected families | Armeni Avloniti Bulgari de' Medici Komnenos Quartano Trivoli |

History

In 961 C.E., the Mediterranean island of Crete, which had been under Muslim rule for almost 150 years, was restored to the Byzantine Empire under the leadership of general-, and future emperor, Nikephoros Phokas. Legend provides that the Byzantine emperor sent 12 noble families from Constantinople, known as the archondopoula, to rule the island of Crete as archons. Of the reconquest of Crete, early 17th-century cartographer Vincenzo Coronelli included the following information in Biblioteca Universale Sacro-Profana:

[...] Many succeeding emperors tried to take back [Crete from the Muslim rulers]; but it was always in vain, and with losses. Finally [...], Romanos II recommended the enterprise to Nikephoros Phokas, who, after seven months of cruel war, on March 4th, 961 [C.E.], destroyed the Saracens, took Candia as [the Byzantines'] main city by arms and led them triumphantly to the Curupa Hippodrome. [He] left St. Nicone to return the Christian religion [to the island], and a colony of twelve noble families to propagate it, who were families Armena; Calojera; Anatolica; Curiaci, i.e., Saturnini, now called Cortazzi; Vespesiani, called Meliseni; called Sutili; Pampini, called Ulastò; Romuli, called Claudi; Aliati, called Scordili; Colonesi, called Coloini; Orsini, called Areulada; and Phoca of Nikephoros Phokas' own blood. [These families were called] the First Ones, later the Arghondopuli [archontopoula], from the word arghia, which means magistrate, rector, or commander, because they dominated the island for many long years ahead of the convulsions of the [Byzantine] Empire, and they were perhaps the greatest enemies of the [ Venetian ] Republic, even though they also benefitted the most [under Venetian rule].[4]

It is likely that Coronelli’s inclusion of the Calogerà in the 12 archontal families of Crete, or archontopoula, is based on Andrea Corner’s (b. 1547 - d. ca. 1616) Storia di Candia, the first literary work to deal exclusively with the island’s history.[5] Similarly, in Revue de l'Orient Latin, Vol. 11 (1908), Louis-Ernest Leroux provides further context in the following passage:

Thus, [ Nikephoros Phokas ] subdued and ransacked the whole island, which for 142 years had been occupied and lorded by barbarians, and he had it settled and left in the form of a colony, for its greater security, under noble families originally from Constantinople [nobili Costantinopolitani] of the Màggiori and of the Senatorial order, namely: the Armeni; the Caleteri; the Anatolici, also called Cortezzi; the Cargenti, that is, Saturnini; the Vespesiani, also called Melissini; […] the Sutili; the Papiliani, also called Vlasti; the Romuli, also called Claudi; the Aliotti, also called Scordilli; the Colonessi, also called Coloini; the Irtini, also called Arculendi; and the Phoca, of the same blood of the Phoca from whom the noble house of Calergi originated.[6]

Numerous other historians have written about the Calogerà family over the centuries. In his 1935 book Calogeras, Antonio Gontijo de Carvalho describes the family's origins:

João Pandiá Calógeras belonged a traditional European family that originated, according to some historians, from the island of Cyprus. The family’s name is associated with a Greek word that translates to "good, old man" or "respectable by age." It derives from the term for an Oriental monk. Formerly, the word also referred to Latin hermits. But the qualifier has since been applied to Greek schismatics, male or female, who observe the rule of St. Basil or St. Marcellus. By its etymology, the word refers only to elder monks, but its use has been extended to include all of the monks living at Mt. Athos.

[...] One fifth century family member, St. Calogerus, exists in universal hagiology and also figures in the family's coat-of-arms. With the schism of the Orthodox Church, one part [of the family] continued in the Roman apostolic rite; the other, more numerous, part adhered to the Eastern creed. In her father's biography The Alexiad, Anna Komnene gives the explanation that, having come to reside in Byzantium, [the Calogerà family] formed alliances with the Komnenos. During the Ottoman conquests, numerous bearers of the Calogerà name fell victim to the Turks.

Breathtaking works such as Chiotis' Historia de Zante, Marmora's Historia de Corfú, Eugene Rizo Rangabé's Livre d'Or de la Noblesse Ionienne, and the Genealogia delle Famiglie Venete each contain biographies of the most distinguished individuals of this important family. In 1431, John Calogerà assumed the post of adviser to Duke Acciaoli in Athens during Attica's period of short-lived sovereignty from [ Catalan rule in] southern Italy. In 1499, Ambassador Matheus Calogerà was sent to Venice on behalf of the Rector of Zante in order to obtain the constitution of [Venetian] territorial property from the Senate. Following the Turkish conquest of Cyprus in 1501 [sic], the Calogerà took refuge on the island of Crete, where they were inscribed in the Golden Book of the Nobility of that island, and they became feudatory barons under Venetian domination.

Several members of the family entered the religious orders; innumerable others were distinguished in war and rendered valuable services to the Republic of Venice, for which they were recognized in various decrees by the Senate and the Doges. In 1537, after the Siege of Suleiman [the Magnificent], families of the nobility, among whom were the main branch of the Calogerà, left Crete to settle in Corfu. The Calogerà were inscribed in the Golden Book of this island in 1644 and thereafter never ceased to appear in every list of its nobles. After the conquest of Crete by the Turks in 1669, another branch, which had remained on the island [of Crete], was to settle in [the city of] Venice, where its members were immediately assimilated into the nobility [sic], [and whose nobility was] confirmed by the Emperor of Austria in 1816 when the Adriatic city was occupied by that mighty nation.

Upon the death of a certain General Calogerà, aide-de-camp to King Constantine of Greece, the senior branch of the Calogerà family of Corfu went extinct, as he left behind no descendants of his own. Among others, the family produced such illustrious individuals as Draco Calogerà (b. 1540), second son of Dimo, who led as Admiral in the Venetian navy, as did relatives Francesco Calogerà (b. 1599) and Zorzi Calogerà (b. 1677). Antonio Calogerà, head of the Venetian branch, was killed in 1684 in the taking of Nauplia, when the Venetian fleet fought to reclaim the Morea [from Ottoman rule]. Several members of the family were awarded knighthoods in the Order of Saint Mark. In the Church of Sant' Antonio in Venice, one finds, surmounted by his coat-of-arms, the tomb of Demetrio Calogerà, who died in 1682 and who was a direct descendant of the main branch of Corfu. John Paul Calogerà, who died in 1702, was the Venetian military governor of Bergamo. Spiridion Calogerà, killed in 1754, was admiral of the arsenal in Corfu. And Marco Calogerà was Bishop of Kotor, Dalmatia, in 1856.[1]

Gontijo de Carvalho is not the only historian to mention a relationship between the Calogerà and Komnenos families. In a description of the events of a 13th-century rebellion against the Venetian domination of Crete, Marcus Antonius Coccius Sabellicus (b. 1436 - d. 1506) writes the following selection in Dell' Historia Venitiana:

[...] But the Calotheri and Anatolici were banished, even if they prided themselves on their ancient parentado[7] to the Emperor of Greece.[8]

In the Brazilian journal Revista de Historia (1961), Volume 22, No. 46, historian Sílvio Fernandes Lopes writes:

In Brazilian onomastics, the names Pandiá and Calógeras evoke, at once, the Greek flavor behind their etymologies: Pandiá reminds the bearer of eclecticism and universalism, while Calógeras conjures up monastic respectability and the wisdom of the elders of St. Basil and St. Marcellus. [The Calógeras family] dates back to an historical and almost mythological Cyprus, where they originated. [...] From beginning all the way to the present, a brilliant genealogical succession can be observed in this family. [...] A Calógeras shines in the hagiological calendar as early as the fifth century, extolling excellent virtues, religious struggles, and the evolution of spiritual postulates in the person of a saint. Byzantium, Athens, Venice, and Crete have all welcomed the Calógeras family through the centuries. In 1644, they appear in Corfu. [Members of this family] sparkled spirits and cultures in the likes of Draco Calógeras, Dino and Francesco, and Zorzi and Antonio, at the head of events in the greater history of the Republic of Venice that would alter the organization and political distribution of the Mediterranean world. For this reason, the arms of Demetrius Calógeras would be featured in the golden and blue panel of the Church of St. Anthony in Venice; John Paul would glow in the military history of Bergamo; Spiridion would die as Admiral of the Arsenal of Corfu in the eighteenth century; and Marco Calógeras would die as Bishop of Cattaro [sic] in Dalmatia in the mid-nineteenth century. Theologians, writers, poets, philologists, philosophers, admirals, generals, sociologists, tribunes, jurists, doctors, and engineers all appear in great numbers in this immense family, which, ever and always illustrious over the centuries, finally arrived in Brazil in 1841 in the person of João Batista Calógeras (grandfather of João Pandiá Calógeras). João Batista, who was a close friend of the Baron de Lafitte—a celebrated banker and minister of King Louis Philippe—lead a financial initiative [on behalf of] that famous man of pecunia [in Brazil].[9]

Giovan Battista di Crollalanza's masterpiece, Dizionario Storico-Blasonico delle Famiglie Nobili e Notabili Italiane, Estinte e Fiorenti (1886), describes the Venetian- and Dalmatian branches of the family:

CALOGERÀ of Venice. — Originally from Corfu, they obtained Septinsular nobility during the epoch of Venetian domination. — In the 16th century, some immigrated to Italy, and a branch settled in Venice; it is from this branch that we are given Angelo, Camaldolese monk, born in Padua, famous for his compilation of philological and scientific booklets known as Calogerà's Collection [la Raccolta Calogerana]. — Marco [Kalogjera], Bishop of Split. — A branch of this family still flourishes in Udine. — ARMS: Of azure [background], a silver, beamless anchor, its shaft accented with a green cedar branch bearing a single, yellow fruit on its left side; all accompanied at the top by a star of eight golden rays.[10]

Reverend Hugh James Rose's arrangement of A New General Biographical Dictionary, Vol. V (1848) mentions the religion of the Corfiote-Venetian branch of the Calogerà family in the article of Angelo Calogerà:

CALOGERÀ, (Angelo,) a priest of the order of the Camaldolesi, and a celebrated philologist of Italy, [was] born at Padua, in 1699, of a noble Greek family of Corfu, which, however, adhered to the Romish Church.[11]

In December of 2008, the Municipality of Blato, in addition to the All Saints Parish of Blato and the Ivo Pilar Institute of Social Sciences in Dubrovnik, commemorated the 120th anniversary of the death of Marko Kalogjera, Bishop of Split and Makarska, by conducting a scientific research conference in his honor. In Biskup Marko Kalogjera o 120. obljetnici smrti: Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa održanog u prosincu 2008. u Blatu, Svezak 1. (translated, Bishop Marko Kalogjera, on the 120th Anniversary of his Death: Proceedings of the Conference Held in December 2008 in Blato, Vol. I), Damir Boras, President of the University of Zagreb, provides an account of the history of the Calogerà family in Croatia:

The Kalogjera family is originally from the Greek realm, and the Greek name means good, old man.

The family's homeland is the island of Cyprus, where the family, distinguished by high-status positions, had lived until the end of the 15th century, when Egyptian Mamluks invaded and plundered the island. [...] The Turks finally conquered [Cyprus] between the years of 1570 and 1571. The Kalogjera family fought in these wars, but eventually they lost all of their possessions and, like many other families, had to flee. The emigration [of the family] from Cyprus began in the late 15th and early 16th centuries and ended in 1570, when the last family members fled, despite a treaty between the defender of the island, Marko Bragadin, and the Turks. Already at the beginning of this migration, many family members had moved to Crete, to the Morea on the Peloponnese—the Peloponnesian branch—and to Corfu and Venice—the Corfiote branch. Thus, in the mid-16th century, we find branches of the family in Crete, Corfu (1540), and in Venice (1550).

The Kalogjera family was split when a smaller branch moved to the Morea [in Greece] and a larger branch moved to [the city of] Venice, and from there some moved to Zadar, Hvar, Korčula, and Dubrovnik. This is the so-called Venetian-Dalmatian branch; the Venetian-Italian branch expanded across Italy to the cities of Padua, Milan, Udine, and Vicenza. Both of these branches form the Venetian branch which, again, is itself a cadet branch of the bloodline from Corfu, Crete, and Cyprus.

The Kalogjera family enjoyed nobility already in Cyprus, then in Crete, in Corfu (1572), and [then also] Nauplian nobility in the Morea.— Niko Kalogjera, Uspomene iz života i rada biskupa Marka Kalogjere st. – Povodom 50-godišnjice njegove smrti, Memories of the Life and Work of Bishop Marko Kalogjera[12]In the past, members of the Kalogjera family were mostly soldiers and priests, but also officials, physicians, and traders. There were several admirals of the Venetian fleet, generals, colonels, military attachés, galley commanders, and ministers, and among them we also find a governor, a consul, and even one imperial governor. Moreover, the family has produced pedagogues, teachers, bishops, and abbots, and among its members we find excellent musicologists and writers as well as merchants and industrialists. Most contemporary family members are scientists, doctors, lawyers, engineers, economists, and musicians, and most are college-educated people. [...][13]

Legacy

Goldsmiths in Dalmatia

In Dalmatia, the Venetian branch of the Calogerà family amassed considerable wealth as goldsmiths on the island of Korčula, becoming one of its most prominent families soon after arriving in the mid-18th century. This cadet branch descends cognatically from the Cortino goldsmithing family of Hvar. In the early 18th century, Don Francesco Calogerà, warden of the Venetian state hospital in Hvar, married the daughter of goldsmith Steffano Cortino, and their son, Steffano Calogerà, became the progenitor of the Kalogjera family of Korčula and the first to adopt the double-barreled nickname of Kalogjera Zlatar, meaning goldsmith.[14]

Notable family members

| Portrait of Marko Kalogjera | |

|---|---|

| |

| Artist | Vlaho Bukovac[15] |

| Year | circa 1880 |

| Medium | oil on canvas |

| Dimensions | 129 cm × 100 cm (51 in × 39 in) |

- Angelo Calogerà, O.S.B. Cam. (c. 1696 - c. 1766): famous Camaldolese monk, writer, and poet in Venice; and Benedictine abbot of San Giorgio Monastery[16]

- Antonio Calogerà (b. 1733 - d. 1772): Venetian Public Notary of Zadar (1770 - 1772); and son of Signor Cavalier Demetrio Calogerà and Maria Maddalena Calogerà of House de' Medici

- Damir Boras, Ph.D. (b. 1951): President of the University of Zagreb (2014–present)

- Domenico Caloyera, O.P. (1915 - 2007): Roman Catholic Archbishop of İzmir, Turkey

- Dražen Kalogjera, Ph.D. (b. 1928 - d. 2016): famous Croatian economist, politician, and Privatization Minister for Croatia's first freely elected government under Franjo Tuđman[17]

- Giovanni Calogiera (c. 17th century - c. 18th century): Venetian governor of Bergamo in 1699[18]

- Goran Kalogjera, O.M.M. (b. 1951): Croatian author and historian; recipient of the State Award of Macedonia ("Medal of St. Clement", 1998), Kočo Racin Award (2005); and Honorary Consul of the Republic of Macedonia in Croatia (2010 – 2019; North Macedonia, 2019 - present)[19][20]

- Ioan Calugherà, Nobile Cretensi (16th century): Cretan-born Grand Boyar and Vistier (court treasurer) of Moldavia under Princes Peter the Cossack and Aaron the Tyrant; served in the campaigns of the Wallachian Prince Michael the Brave against the Turkish incursions of modern-day Romania[21]

- Ioannis Kalogeras (b. 1876 - d. 1957): Greek military general, Member of Parliament (Athens), and Minister General Director of Thrace

- Irène Caloyera (19th century): wife of Prince Démètre Mavroyeni, Wallachian Vice-Consul to Austria and Vojvoda of Mycone[22]

- Ivana Kalogjera-Brkić (b. 1962): famous Croatian journalist and author; former chief adviser to the Croatian Minister of Science; and founder of Nismo Same (translated, We Are Not Alone), an organization dedicated to supporting cancer patients in Croatia[23]

- Jakša Kalogjera (b. 1910 - d. 2007): Croatian engineer declared Righteous Among the Nations by Yad Vashem and the State of Israel in 2001 for assisting Jews during the Holocaust[24]

- João Pandiá Calógeras (b. 1870 - 1934): Federal Deputy for Minas Gerais, Brazil; Minister of Agriculture, Commerce, and Industry (1914); Minister of the Economy (1916); and the first and only civilian Minister of War in the history of the Republic of Brazil

- Lucille Borel de Brétizel, Viscountess de Rambures (b. 1908; née Calógeras): wife of Bernard Borel de Brétizel, Viscount de Rambures

- St. Makarios Kalogeras of Patmos, Teacher of the Nation (b. 1688 - d. 1737): Greek Orthodox saint who founded the Patmian School in Patmos, Greece[25]

- Marko Kalogjera, C.C., O.P. (b. 1819 - d. 1888): Roman Catholic Bishop of Split-Makarska, Croatia, and Kotor, Montenegro; and Baron of the Austrian Imperial Order of Leopold; largely credited with preserving the Glagolitic script[26]

- Marko Kalogjera (Old Catholic Church) (b. 1877 - d. 1956): founder and first Bishop of the Old Catholic Church of Croatia[27]

- Nikica Kalogjera, M.D. (b. 1930 - d. 2006): Serbian-born Croatian physician; acclaimed composer, director, and music producer; and husband of singer Ljupka Dimitrovska

- Pjer Šimunović: Croatian Ambassador to the United States (August 2017 – present); former Director of Croatia's National Security Council (April 2016 - August 2017); former Croatian Ambassador to Israel (August 2012 - April 2016); and maternal first cousin, twice-removed, of Jakša Kalogjera[28]

- Stjepan Kalogjera, M.D. (b. 1934): Serbian-born Croatian physician; acclaimed pop music composer, conductor, and music producer; and husband of pop singer and model Maruška Šinković-Kalogjera

- Vanja Kalogjera (b. 1936 - d. 2005): Croatian economist and Ambassador to the United Arab Emirates (1991 - 1996); husband of famous journalist and diplomat Silvija Luks-Kalogjera[29]

Place names

Various locations have been named in honor of the Calogerà family.

- Ošljak (island): The small island of Ošljak, off the coast of Zadar, was previously known as Calogerà, or Kaluđera,[30] named after the Calogerà [Kalogjera, Kalogera] family of Zadar who possessed it and built their summer residence and gardens there.[31][32] The remains of the Calogerà family mansion and gardens are protected cultural and historical landmarks.[33] Today, some locals still refer to the island as Kalogera. The legacy of the Calogerà family is preserved in the island's Italian name, Calugerà. In Preko: Povijesne, Geografske, Folklorističke, i Kulturne Crtice (1924), Dr. Josip Marčelić, Bishop of Dubrovnik, writes the following excerpt:

Some still call [the island] Kalogera, the name of its first possessors, who received the island [as a gift from] from the Venetian Republic. The Kalogera family was probably from Crete, and they were ardent supporters of the Republic in the Cretan military. [...] The [area] of the island is elliptical and measures 2,300 meters. The island rises in the form of a cone 60m above the surface of the sea. On the northern side of the islet, two circular buildings are visible, and the walls are still solid. They were built by the first possessor of the island, Levantin Kalogera. These are old mills, two windmills, [which were] used in the past by the inhabitants of the surrounding villages, when there were no bigger boats nearby.[31]

- Pandiá Calógeras State School: Prior to World War II, the school had been named after Benito Mussolini. In 1942, this name was stripped, and it was re-branded in honor of João Pandiá Calógeras. It is located in the vicinity of Carlos Chagas Square in Belo Horizonte, Brazil.[34]

Gallery

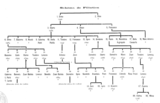

Family Trees

.png)

.png) Venetian branch, cadet of Corfiote branch, illustrated by Teodoro Toderini ca. 1873 and preserved at the State Archives of Venice[37]

Venetian branch, cadet of Corfiote branch, illustrated by Teodoro Toderini ca. 1873 and preserved at the State Archives of Venice[37]

Coats of Arms

According to Niko Kalogjera in Memories, there were three coats of arms that belonged to different branches of the family.

Cypriot-Peloponnese branch — On a silver background atop an azure border, decorated with three golden stars, is a red sun, and at the bottom there is a burning tower ([or] three burning towers) in natural color. This coat of arms appears in the will and testament of Ivan [Italian, Giovanni], the military governor of Bergamo, dated 8 June 1698.

Corfiote coat of arms — Beneath the leafy branch of a tree, or palm tree, stands a monk with a rosary in his hand. This coat of arms is in the archives of the Corfu Museum, and a stone version exists in the lobby of the University of Padua just to the left of the entrance.Dalmatian coat of arms — In the upper half of the field, a lion exceeds three mountains or islands. The lower half of the field is divided, from left to right, by an oblique furrow into two smaller fields. The first [signifies] a meadow; the other, arable land.

— Damir Boras, in "A Review of the Kalogjera Genus"[38]

Coat of arms: Corfu

Coat of arms: Corfu

Coat of arms: Dalmatia

Coat of arms: Dalmatia

Coat of arms of Bishop Marko Kalogjera (Roman Catholic)

Coat of arms of Bishop Marko Kalogjera (Roman Catholic) Stamp of Antonio Calogerà of Zadar, used from 1768 until 1772

Stamp of Antonio Calogerà of Zadar, used from 1768 until 1772 Coat of arms: Cyprus, ecclesiastical arms of abbot Angelo Calogera, featuring the original Cypriot ensign

Coat of arms: Cyprus, ecclesiastical arms of abbot Angelo Calogera, featuring the original Cypriot ensign Plaque of Nikolaos Kalogeras on the Five-Terraced House of Monemvasia, Greece

Plaque of Nikolaos Kalogeras on the Five-Terraced House of Monemvasia, Greece

Miscellaneous

License of Don Liberale Calogerà, Venetian Consul to Ottoman Cyprus, 1721 - 1724.

License of Don Liberale Calogerà, Venetian Consul to Ottoman Cyprus, 1721 - 1724. goldsmith's booklet of the Kalogjera family of Blato, Croatia, from 1741: template for an icon frame[40]

goldsmith's booklet of the Kalogjera family of Blato, Croatia, from 1741: template for an icon frame[40] Brazilian postage stamps featuring portrait of João Pandiá Calógeras

Brazilian postage stamps featuring portrait of João Pandiá Calógeras envelope stamped in commemoration of Joao Pandias Calogeras

envelope stamped in commemoration of Joao Pandias Calogeras school banner created in homage to João Pandiá Calógeras

school banner created in homage to João Pandiá Calógeras Coat of arms: Albania

Coat of arms: Albania

Notes

- Antonio Gontijo de Carvalho, Calogeras, Companhia Editora Nacional, São Paulo, 1935, translated from Portuguese.

- See Silvio Fernandes Lopes, "João Pandiá Calógeras" in Revista de Historia, p. 290.

- See von Rosenfeld, Wappenbuch des Königreichs Dalmatien, p. 101.

- Calojera in bold. See Coronelli, Biblioteca Universale Sacro-Profana, p. 940.

- Andrea Corner, Storia di Candia, Biblioteca Nazionale Marciana (BNM), Venice, It. VI. 286 (5985)

- fr:Ernest Leroux, Revue de l'Orient Latin, Vol. 11, 28 Rue Bonaparte, Paris, 1908, p. 111, translated from French, Caleteri in bold.

- i.e., cognatic kinship

- Marco Antonio Sabellico, Dell'Historia Venitiana, Appresso Gio: Maria Sauioni, Venice, 1668, p. 124, translated from Italian, Calotheri in bold, accessed via Google Books on 16 December 2019.

- See Sílvio Fernandes Lopes, "João Pandia Calógeras" in Revista de Historia, pp. 289-290.

- Giovan Battista di Crollalanza, Dizionario storico-blasonico delle famiglie nobili e notabili italiane estinte e fiorenti, Vol. I, p. 202, Il Giornale Araldica, Pisa, 1866, translated from Italian.

- See James Rose, A New General Biographical Dictionary, p. 432.

- Niko Kalogjera, Uspomene iz života i rada biskupa Marka Kalogjere st. – Povodom 50-godišnjice njegove smrti, Štamparija "Gaj", Zagreb, 1938, p. 52, translated from Serbo-Croatian.

- See Boras, "Prikaz Roda Kalogjera" in Biskup Marko Kalogjera o 120. obljetnici smrti, p. 13.

- See Lupis, "Zlatarska bilježnica obitelji Kalogjera iz Blata na otoku Korčuli" in Peristil.

- Vera Kružić Uchytil, Vlaho Bukovac : Život i djelo (1855-1920), Nakladni zavod Globus, Zagreb, 2005, pp. 44-48, 340–341, 345–346.

- Cesare De Michelis, Angelo Calogerà, in Dizionario biografico degli italiani, vol. 16, Roma, Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana, 1973.

- Restructuring of the Economic Elites after State Socialism, p. 224, , accessed via Google Books 1 November 2018

- Visite Adlimina Apostolorum, 1702 - 1850, Part I, p. 74, , published 2 December 2014

- Počasni konzul: Goran Kalogjera, , Macedonian Consulate in Rijeka, accessed 1 November 2018

- Mark Abramoff, "Macedonian Consul in Croatia asks Government: What sort of monkeys are you appointing as Ambassadors!?", Mina Report, 10 December 2018, accessed 16 December 2019.

- Istoria lui Mihai Viteazul, Vol. I, , p. 183 et al., accessed 2 November 2018

- Livre d'or de la noblesse phanariote en Grèce, en Roumanie, en Russie et en Turquie, Eugène Rangabé, 1892, p. 82

- "Tko sam ja", Nismo Same, accessed 20 December 2019.

- "Kalogjera Family", The Righteous Among the Nations Database, Yad Vashem, accessed 1 November 2018

- "St. Makarios Kalogeras of Patmos (+1737)", Blogspot, accessed 5 November 2018

- Vinicije Lupis, Biskup Marko Kalogjera o 120. obljetnici smrti, University of Zagreb, 2008.

- Old Catholic Church of Croatia, "NAŠA POVIJEST – Hrvatska Starokatolička crkva", Zagreb, accessed 14 April 2018.

- "A Good Friend: Interview with Croatian Ambassador Pjer Simunovic", , accessed 1 November 2018

- "Preminuo Vanja Kalogjera", , accessed 1 November 2018

- Ante Brižić, "Vlasnici Ošljaka" in Naši školji, No. 13, Municipality of Preko, 2015, p. 124, translated from Serbo-Croatian.

- Josip Marčelić, "Ošljak" in PREKO, Historical, Geographical, Folklore, and Cultural Dash, Tisak Dubrovačke Hrvatske Tiskare, Dubrovnik, 1924, pp. 76-83, translated from Serbo-Croatian.

- Patrizia Licini, "Lorenzo Licini (1725-1802): Surveyor of Dalmatia and Count of Poljica", Geoadria, Vol. 15, No. 2, Croatian Geographical Society, Zadar, 2010, p. 373.

- Općina Preko, "Urbanistički Plan Uređenja za GP Ošljak (u Cijelosti)", Općina Preko, Studio Urbana, d.o.o. - Zagreb, plan br. 10/07, 2018, translated from Serbo-Croatian, accessed 16 December 2019.

- "Educação em Foco", accessed 21 December 2019.

- Eugene Rizo-Rangabé, Livre d'Or de la Noblesse Ionienne (Golden Book of the Ionian Nobility), Vol. I (Corfu), Maison d' Editions "Eleftheroudakis", Athens, 1925, translated from French.

- See Boras, "Prikaz Roda Kalogjera" in Biskup Marko Kalogjera o 120. obljetnici smrti, p. 15.

- See Toderini, "Genealogy of a branch of the Calogerà family in Venice" in Miscellanea Codici.

- See Boras, "Prikaz Roda Kalogjera" in Biskup Marko Kalogjera o 120. obljetnici smrti, p. 14.

- See von Rosenfeld, Wappenbuch des Königreichs Dalmatien, Table 58.

- See Lupis, "Zlatarska bilježnica obitelji Kalogjera iz Blata na otoku Korčuli" in Peristil.

Bibliography

- Boras, Damir (5 December 2008). "Prikaz Roda Kalogjera" [A Review of the Kalogjera Genus] (PDF). In Vinicije Lupis (ed.). Biskup Marko Kalogjera o 120. obljetnici smrti: Zbornik radova znanstvenog skupa održanog u prosincu 2008. u Blatu [Bishop Marko Kalogjera on the 120th Anniversary of His Death: Proceedings of a Scientific Conference Held in Blato in December 2008]. Znanstveni Skup Biskup Marko Kalogjera – O 120. obljetnici smrti (in Croatian). Volume 1 (500 kom. ed.). Blato: Općina Blato; Župa Svih svetih Blato; and Institut društvenih znanosti „Ivo Pilar” Dubrovnik. pp. 11–20. ISBN 978-953-99328-5-3.

- Coronelli, Vincenzo (1707). "CAND". Biblioteca Universale Sacro-Profana, Antico-Moderna, In cui si spiega con ordine Alfabetico Ogni Voce, Anco Straniera, Che può avere significato nel nostro Idioma Italiano (in Italian). Antonio Tivani. Volume 7.

- Fernandes Lopes, Sílvio (1961). "João Pandia Calógeras" (PDF). Revista de Historia (in Portuguese). Sao Paulo: University of São Paulo. Volume 22 (No. 46). ISSN 2316-9141.

- Ganza, Milka (2004). "Uspomene i sjećanja na obitelj Kalogjera", Blatski Ljetopis, pp. 291-306 (in Croatian). Zagreb: Društvo Blaćana i prijatelja Blata u Zagrebu. ISSN 1332-7283.

- Gontijo de Carvalho, Antonio (1935). Calogeras (PDF) (in Portuguese). São Paulo: Companhia Editora Nacional.

- James Rose, B.D., Rev., Hugh (1848). "Calogera". A New General Biographical Dictionary: In 12 Volumes. Volume 5. London: B. Fellowes, Ludgate Street, et al. Retrieved 18 June 2020.CS1 maint: multiple names: authors list (link)

- Lupis, Vinicije (2009). "Zlatarska Bilježnica Obitelji Kalogjera iz Blata na Otoku Korčuli" [Goldsmith's Notebook of the Kalogjera Family of Blato on the Island of Korčula]. Peristil: Zbornik Radova za Povijest Umjetnosti [Peristil: Proceedings of Art History] (in Croatian). Zagreb: Croatian Society of Art Historians. Volume 52 (No. 1). ISSN 1849-6547. Archived from the original (PDF) on 19 June 2013 – via https://hrcak.srce.hr/152960.

- de Michelis, Cesare (1973). "Angelo Calogerà", Dizionario Biografico degli Italiani, Vol. 16. Rome: Istituto dell'Enciclopedia Italiana.

- Rizo-Rangabé, Eugene (1925). Livre d'Or de la Noblesse Ionienne, I (Corfou) (in French). University of Crete, Rethymno: Maison d'Editions "Eleftheroudakis".

- Rizo-Rangabé, Eugene (2017). Livre d'Or de la Noblesse Ionienne, Corfou (re-print) (in French). Switzerland: Ariston Books. ISBN 978-294-06034-1-1.

- von Rosenfeld, Carl Georg Friedrich Heyer (1873). Wappenbuch des Königreichs Dalmatien [Armorial of the Kingdom of Dalmatia] (in German). J. Siebmachers grosses und allgemeines Wappenbuch, Vierten Bandes, Dritte Abtheilung. Nürnberg: Bauer und Raspe.

- Toderini, Teodoro. "Genealogy of a branch of the Calogerà family in Venice" (1873) [historical record]. Miscellanea codici, Storia veneta, Series: Cittadinanze Toderini (Vol. II, B-F, b. 5), p. 459. Venice: State Archives of Venice, Archivio di Stato di Venezia.

- Varfi, Gjin (2000). Heraldika Shqiptare. Tirana: Shtëpia Botuese Dituria. ISBN 978-999-27318-5-7.

External Links

- "NAŠA POVIJEST – Hrvatska Starokatolička crkva". hrvatska-starokatolicka-crkva.com.

.jpg)