Zakynthos

Zakynthos (also spelled Zakinthos; Greek: Ζάκυνθος, romanized: Zákynthos [ˈzacinθos] (![]()

Zakynthos Ζάκυνθος | |

|---|---|

View of Zakynthos City | |

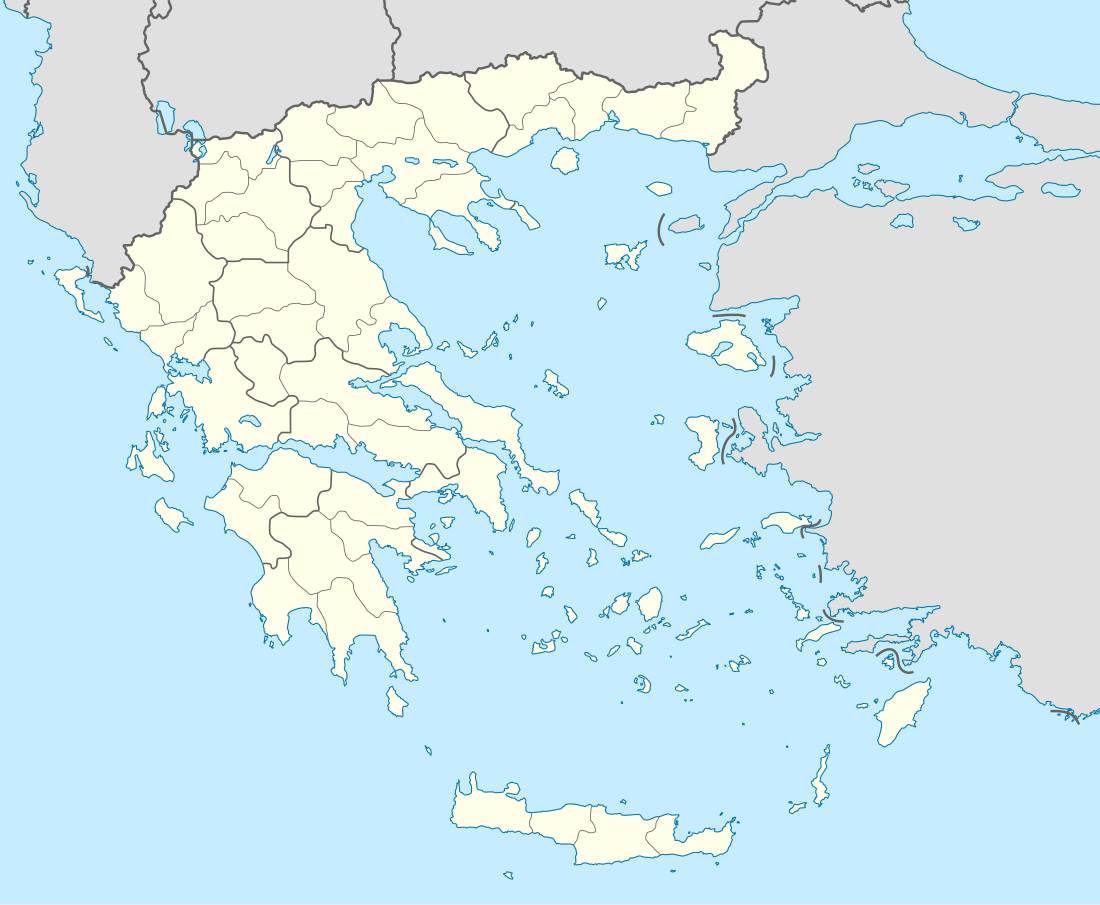

Zakynthos within Greece | |

Zakynthos Zakynthos within Greece | |

| Coordinates: 37°48′N 20°45′E | |

| Country | |

| Region | Ionian Islands |

| Capital | Zakynthos |

| Government | |

| • Vice Governor | Georgios Stasinopoulos |

| • Mayor | Nikitas Aretakis |

| Area | |

| • Total | 405.55 km2 (156.58 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 40,759 |

| • Density | 100/km2 (260/sq mi) |

| Demonym(s) | Zakynthian |

| Time zone | UTC+2 |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+3 (EEST) |

| Postal codes | 29x xx |

| Area codes | 2695 |

| Car plates | ΖΑ |

| Website | www |

Zakynthos is a tourist destination,[4] with an international airport served by charter flights from northern Europe. The island's nickname is "the Flower of the Levant", bestowed upon it by the Venetians who were in possession of Zakynthos from 1484 to 1797.

History

Ancient history

The ancient Greek poet Homer mentioned Zakynthos in the Iliad and the Odyssey, stating that its first inhabitants were the son of King Dardanos of Arcadia, called Zakynthos, and his men. Before being renamed Zakynthos, the island was said to have been called Hyrie. Zakynthos was then conquered by King Arkesios of Kefalonia, and then by Odysseus from Ithaca. Zakynthos participated in the Trojan War and is listed in the Homeric Catalogue of Ships which, if accurate, describes the geopolitical situation in early Greece at some time between the Late Bronze Age and the eighth century BCE. In the Odyssey, Homer mentions 20 nobles from Zakynthos among a total of 108 of Penelope's suitors.[5]

The Athenian military commander Tolmides concluded an alliance with Zakynthos during the First Peloponnesian War sometime between 459 and 446 BC. In 430 BC, the Lacedaemonians made an unsuccessful attack upon Zakynthos. The Zakynthians are then enumerated among the autonomous allies of Athens in the disastrous Sicilian expedition. After the Peloponnesian War, Zakynthos seems to have passed under the supremacy of Sparta because in 374 BC, Timotheus, an Athenian commander, on his return from Kerkyra, landed some Zakynthian exiles on the island and assisted them in establishing a fortified post. These exiles must have belonged to the anti-Spartan party as the Zakynthian rulers applied for help to the Spartans who sent a fleet of 25 to the island.[5][6][7]

The importance of this alliance for Athens was that it provided them with a source of tar. Tar is a more effective protector of ship planking than pitch (which is made from pine trees). The Athenian trireme fleet needed protection from rot, decay and the teredo, so this new source of tar was valuable to them. The tar was dredged up from the bottom of a lake (now known as Lake Keri) using leafy myrtle branches tied to the ends of poles. It was then collected in pots and could be carried to the beach and swabbed directly onto ship hulls.[8] Alternatively, the tar could be shipped to the Athenian naval yard at the Piraeus for storage.[9]

Philip V of Macedon seized Zakynthos in the early 3rd century BC when it was a member of the Aetolian League. In 211 BC, the Roman praetor Marcus Valerius Laevinus took the city of Zakynthos with the exception of the citadel. It was afterwards restored to Philip V of Macedon. The Roman general Marcus Fulvius Nobilior finally conquered Zakynthos in 191 BC for Rome. In the Mithridatic War, it was attacked by Archelaus, the general of Mithridates, but he was repulsed.[5]

Medieval and modern age

After the fall of the Byzantine Empire, it was held by the Kingdom of Naples, the Ottoman Turks, the Republic of Venice, the French, Russians, British, Italians and Germans.

World War II

During the Nazi occupation of Greece, Mayor Karrer and Bishop Chrysostomos refused Nazi orders to turn in a list of the members of the town's Jewish community for deportation to the death camps. Instead they hid all (or most) of the town's Jewish people in rural villages. According to some sources, all 275 Jews of Zakynthos survived the war.[10][11] Both were later recognized as Righteous among the Nations by Yad Vashem. In contrast, over 80% of Greek Jews were deported to death camps and perished in the Holocaust.[12]

Earthquakes

Zakynthos was hit by a 7.3-magnitude earthquake in 1953, which destroyed most of the buildings on the island. Subsequently, all buildings have been fortified to protect against further tremors. On 26 October 2018, a 6.4-magnitude earthquake south of the island caused no injuries but damaged the local pier and a 13th Century monastery.[13]

Geography

Zakynthos lies in the eastern part of the Ionian sea, around 20 kilometres (12 miles) west of the Greek (Peloponnese) mainland. The island of Kefalonia lies 15 kilometres (9 miles) to the north. It is the southernmost of the main group of the Ionian islands (not counting distant Kythira). Zakynthos is about 40 kilometres (25 miles) long and 20 kilometres (12 miles) wide, and covers an area of 405.55 km2 (156.58 sq mi).[3] Its coastline is approximately 123 km (76 mi) long. According to the 2011 census, the island has a population of 40,759.[14] The highest point is Vrachionas, at 758 metres (2,487 feet).

Zakynthos has the shape of an arrowhead, with the "tip" (Cape Skinari) pointing northwest. The western half of the island is a mountainous plateau and the southwest coast consists mostly of steep cliffs. The eastern half is a densely populated fertile plain with long sandy beaches, interrupted with several isolated hills, notably Bochali which overlooks the city and the peninsula of Vasilikos in the northeast. The peninsulas of Vassilikos to the north and Marathia to the south enclose the wide and shallow bay of Laganas on the southeast part of the island.

The capital, which has the same name as the prefecture, is the town of Zakynthos. It lies on the eastern part of the northern coast. Apart from the official name, it is also called Chora (i.e. the Town, a common denomination in Greece when the name of the island itself is the same as the name of the principal town). The port of Zakynthos has a ferry connecting to the port of Kyllini on the mainland. Another ferry connects the village of Agios Nikolaos to Argostoli on Kefalonia. Minor uninhabited islands around Zakynthos included in the municipality and regional unit are: Marathonisi, Pelouzo, Agios Sostis in the Laganas bay; Agios Nikolaos, near the eponymous harbor on the northern tip; and Agios Ioannis near Porto Vromi on the western coast.

Flora and fauna

The mild Mediterranean climate and plentiful winter rainfall endow the island with dense vegetation. The principal agricultural products are olive oil, currants, grapes and citrus fruit. The Zante currant is a small sweet seedless grape that is native to the island.

The Bay of Laganas is the site of the first National Marine Park and the prime nesting area for loggerhead sea turtles (Caretta caretta) in the Mediterranean.

Climate

| Climate data for Zakynthos (1961–1990) | |||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Month | Jan | Feb | Mar | Apr | May | Jun | Jul | Aug | Sep | Oct | Nov | Dec | Year |

| Record high °C (°F) | 20.2 (68.4) |

21.4 (70.5) |

24.2 (75.6) |

25.6 (78.1) |

34.2 (93.6) |

35.8 (96.4) |

42.2 (108.0) |

38.4 (101.1) |

36.8 (98.2) |

30.4 (86.7) |

26.6 (79.9) |

22.2 (72.0) |

42.2 (108.0) |

| Average high °C (°F) | 14.4 (57.9) |

14.5 (58.1) |

16.1 (61.0) |

18.9 (66.0) |

23.4 (74.1) |

27.8 (82.0) |

30.7 (87.3) |

30.6 (87.1) |

27.6 (81.7) |

23.0 (73.4) |

19.0 (66.2) |

15.8 (60.4) |

21.8 (71.2) |

| Daily mean °C (°F) | 11.3 (52.3) |

11.5 (52.7) |

12.9 (55.2) |

15.5 (59.9) |

19.8 (67.6) |

24.1 (75.4) |

26.7 (80.1) |

26.6 (79.9) |

23.8 (74.8) |

19.6 (67.3) |

15.8 (60.4) |

12.8 (55.0) |

18.4 (65.1) |

| Average low °C (°F) | 8.1 (46.6) |

8.2 (46.8) |

9.2 (48.6) |

11.1 (52.0) |

14.4 (57.9) |

18.2 (64.8) |

20.4 (68.7) |

20.9 (69.6) |

18.8 (65.8) |

15.7 (60.3) |

12.5 (54.5) |

9.6 (49.3) |

13.9 (57.0) |

| Record low °C (°F) | −2.6 (27.3) |

−2.0 (28.4) |

0.0 (32.0) |

2.6 (36.7) |

5.0 (41.0) |

8.4 (47.1) |

12.0 (53.6) |

13.4 (56.1) |

10.8 (51.4) |

5.2 (41.4) |

2.8 (37.0) |

0.2 (32.4) |

−2.6 (27.3) |

| Average precipitation mm (inches) | 150.4 (5.92) |

112.8 (4.44) |

89.6 (3.53) |

51.3 (2.02) |

17.0 (0.67) |

7.2 (0.28) |

5.0 (0.20) |

9.1 (0.36) |

25.4 (1.00) |

146.5 (5.77) |

159.1 (6.26) |

169.9 (6.69) |

943.3 (37.14) |

| Average precipitation days (≥ 1.0 mm) | 12.8 | 11.3 | 8.2 | 6.1 | 2.5 | 1.1 | 0.5 | 0.9 | 2.8 | 8.1 | 11.0 | 13.2 | 78.5 |

| Average relative humidity (%) | 74.3 | 72.8 | 72.8 | 71.7 | 67.8 | 62.8 | 59.3 | 61.2 | 66.7 | 71.7 | 76.0 | 75.3 | 69.4 |

| Source: NOAA[15] | |||||||||||||

Sights

Famous landmarks include the Navagio beach, a cove on the northwest shore isolated by high cliffs and accessible only by boat. Numerous natural "blue caves" are cut into cliffs around Cape Skinari, and accessible only by small boats.[16] Keri, on the south of the island, is a mountain village with a lighthouse. The whole western shore from Keri to Skinari contains rock formations including arches.[17]

Northern and eastern shores feature numerous wide sandy beaches, some of which attract tourists in summer months. The largest resort is Laganas. Marathonissi islet (also known as "Turtle Island") near Limni Keriou has tropical vegetation, turquoise waters, beaches, and sea caves. Bochali hill above the Zakynthos town contains a small Venetian castle.

Administration

Zakynthos is a separate regional unit of the Ionian Islands region, and the only municipality of the regional unit. The seat of administration is Zakynthos, the main town of the island.

Prefecture

As a part of the 2011 Kallikratis government reform, the regional unit Zakynthos was created out of the former prefecture Zakynthos (Greek: Νομός Ζακύνθου). The prefecture had the same territory as the present regional unit. At the same reform, the current municipality Zakynthos was created out of the 6 former municipalities:[18]

Population and demographics

- 1889: 44,070 (island), 18,906 (city)

- 1896: 45,032 (island), 17,478 (city)

- 1900: 42,000

- 1907: 42,502

- 1920: 37.482

- 1940: 42,148

- 1981: 30,011

- 1991: 32,556 (island), 13,000 (city)

- 2001: 38,596

- 2011: 40,759

In 2006, there were 507 births and 407 deaths. Zakynthos is one of the regions with the highest population growth in Greece. It is also one of the only three prefectures (out of 54) in which the rural population has a positive growth rate. In fact, the rural population's growth rate is higher than that of the urban population in Zakynthos. Out of the 507 births, 141 were in urban areas and 366 were in rural areas. Out of the 407 deaths, 124 were in urban areas and 283 were in rural areas.

The population of Zakynthos suffers from an exceptionally high rate of declared blindness of about 1.8%. That rate is about nine times the average in Europe, according to the WHO and in April 2012 the Greek Ministry of Health and Social Solidarity launched an investigation into disability benefits as out of the 650 receiving them at least 600 were falsely declared blind.[19]

Culture

Literature

Since Zakynthos was under the rule of the Venetian Republic it had closer contact with Western literary trends than other areas inhabited by Greek people.

An early literary work from the island is the Rimada, a 16th-century romance in verse about Alexander the Great.[20] Notable early writers include Tzanes Koroneos (author of Andragathemata of Bouas, a work of historical fiction),[21][22] Nikolaos Loukanis (a 16th-century Renaissance humanist),[23] Markos Defaranas (1503–1575, possibly the author of the Rimada),[24] Pachomios Roussanos (1508–1553, a scholar and theologian),[25] and Antonio Catiforo (1685–1763, a grammarian and satirist).[26][27][28]

Towards the end of the 18th century, the so-called Heptanese School of Literature developed, consisting mainly of lyrical and satirical poetry in the vein of Romanticism prevalent throughout Europe at the time. It also contributed to the development of modern Greek theatre. An important poet of this school was Zakynthian Dionysios Solomos; another was Nikolaos Koutouzis, who also figures prominently in the Heptanese School of Painting. Others include Georgios Tertsetis (1800–1873, politician, poet, and historian).

Transport

The island is covered by a network of roads, particularly the flat eastern part, with main routes linking the capital with Volimes on north, Keri on the south, and peninsula Vassiliki on the west. The road between Volimes and Lithakia is the spine of the western half of the island.

The island has one airport, Zakynthos International Airport (on former GR-35) which connects flights with other Greek airports and numerous tourist charters. It is located 4.3 km (2.7 mi) from Zakynthos and opened in 1972.

Zakynthos also features two ports: the main port, located in the capital, and another in the village of Agios Nikolaos. From the main port there is a connection to the port of Kyllini, which is the usual route for arrivals to the island by sea from the mainland. From the port of Agios Nikolaos there is a connection to the island of Kefalonia.

Science

Two academic departments belonging to the Technological Educational Institute of the Ionian Islands have been located on Zakynthos since 2003. The department of Environmental Technology and Ecology has developed laboratory and field station infrastructures along Zakynthos and the Strofades islets. The other department is the Protection and Conservation of Cultural Heritage.[29]

Freshwater resources on Zakynthos are limited, and as a result a Greek-Norwegian educational collaboration is being established on the island. The Science Park Zakynthos is a collaboration between the Technological Educational Institute of the Ionian Islands (TEI), the Norwegian University of Life Sciences (UMB), and the Therianos Villas and Therianos Family Farm on Zakynthos.

Notable people

_statue%2C_Zakynthos_City%2C_Greece_01.jpg)

Among the most famous Zakynthians is the 19th-century poet Dionysios Solomos, whose statue adorns the main town square. The Italian poet Ugo Foscolo was born in Zakynthos. The famous Renaissance surgeon and anatomist Andreas Vesalius died on Zakynthos after being shipwrecked while making a pilgrimage to the Holy Land. His body is thought to have been buried on the island but the site has been lost. Early 19th-century poet and playwright Elizabeth Moutzan-Martinegou was also born there.

Tourism

Since the mid 1980s, Zakynthos (known as Zante) has become a hub for 18-to-30-year-old tourists, leading to Alykanas and Laganas (formerly quiet villages) becoming hometowns of clubbing hotels,[30] nightclubs, bars and restaurants.[31] Alykes is by far the most beautiful destination on the island.

Gallery

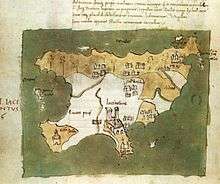

Map of the island by Cristoforo Buondelmonti (1420)

Map of the island by Cristoforo Buondelmonti (1420) Bust of Ugo Foscolo

Bust of Ugo Foscolo Church at Kato Gerakari

Church at Kato Gerakari- Saint Mark's Catholic church, Zakynthos town

Sekania beach, Laganas bay

Sekania beach, Laganas bay Porto Vromi

Porto Vromi Cultural centre, Dionysios Solomos Square

Cultural centre, Dionysios Solomos Square

See also

Citations

- "Zante". Collins English Dictionary. HarperCollins. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "Zante" (US) and "Zante". Oxford Dictionaries UK Dictionary. Oxford University Press. Retrieved 5 May 2019.

- "Population & housing census 2001 (incl. area and average elevation)" (PDF) (in Greek). National Statistical Service of Greece. Archived from the original (PDF) on 21 September 2015.

- Hiltner, Stephen (7 August 2019). "Shipwrecks and Secluded Beaches: Exploring the Greek Island of Zakynthos". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331. Retrieved 7 January 2020.

- Smith, William (1854). Dictionary of Greek and Roman Geography. John Murray.

- Thucydides. History of the Peloponnesian War. Translated by Richard Crawley. 2.8. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Diodorus Siculus (1946). Library of History. Volume 4. Translated by C. H. Oldfather. Loeb Classical Library. 11.84.7. ISBN 978-0-674-99413-3. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Herodotus (1910). History of Herodotus. Translated by George Rawlinson. 4.195. Retrieved 24 July 2010.

- Hale, John (2009). Lords of the Sea: The Epic Story of the Athenian Navy and the Birth of Democracy. New York: Viking. p. 107. ISBN 978-0-670-02080-5.

- "Zakynthos". United States Holocaust Memorial Museum. Retrieved 1 August 2017.

- "The miraculous story of the Jews of Zakynthos". The Jerusalem Post | JPost.com. Retrieved 10 January 2018.

- History of the Jewish Communities of Greece, American Friends of the Jewish Museum of Greece Archived 2007-06-29 at the Wayback Machine, afjmg.org; accessed 7 December 2014.

- "Zakynthos earthquake: Greek island shaken by 6.4 tremor". www.bbc.co.uk. Retrieved 26 October 2018.

- Απογραφή Πληθυσμού – Κατοικιών 2011. ΜΟΝΙΜΟΣ Πληθυσμός (in Greek). Hellenic Statistical Authority.

- "Zakinthos Airport Climate Normals 1961–1990". National Oceanic and Atmospheric Administration. Retrieved 2 March 2015.

- "Zakynthos Blue Caves: The Blue Caves of Zakynthos Greece, Ionian". Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- Carole Simm. "Beaches in Zakynthos, Greece". USA Today Travel. Retrieved 18 June 2015.

- "Kallikratis reform law text" (PDF).

- Angelos, James (3 April 2012). "'Island of the Blind' Riles a Greek Public Facing Cutbacks". The Wall Street Journal.

- Moennig, Ulrich (2016). "A Hero without Borders: 1. Alexander the Great in Ancient, Byzantine and Modern Greek Tradition". In Cupane, Carolina; Krönung, Bettina (eds.). Fictional Storytelling in the Medieval Eastern Mediterranean and Beyond. Leiden: Brill. pp. 159–89.

- "Νέα έκδοση: Roberta Angiolillo: Tzane Koroneos. Le gesta di Mercurio Bua, Edizioni dell'Orso Alessandria 2013 (book review)". early-modern-greek.org.

- Angiolillo, Roberta, ed. (2013). Tzane Koroneos. Le gesta di Mercurio Bua. Alessandria: Edizioni dell'Orso. ISBN 978-88-6274-458-4.

- Bruce Merry (2004). Encyclopedia of Modern Greek Literature. Greenwood Publishing Group. p. 192. ISBN 978-0-313-30813-0.

- Molly Greene (2010). Catholic Pirates and Greek Merchants: A Maritime History of the Early Modern Mediterranean. Princeton University Press. pp. 37–. ISBN 978-0-691-14197-8.

- Benisis, Marios (2006). "Ο ΠΑΧΩΜΙΟΣ ΡΟΥΣΑΝΟΣ ΚΑΙ ΤΟ ΣΥΓΓΡΑΦΙΚΟ ΤΟΥ ΕΡΓΟ". Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - "Catiforo, Antonio (1685–1763)".

- Margherita Losacco (2003). Antonio Catiforo e Giovanni Veludo: interpreti di Fozio (in Italian). EDIZIONI DEDALO. ISBN 978-88-220-5807-2.

- Falcetta, Angela (2010). "Diaspora ortodossa e rinnovamento culturale: il caso dell'abate greco-veneto Antonio Catiforo (1685–1763)". Cromohs (15): 1–24. doi:10.13128/Cromohs-15468.

- culture.teiion.gr Technological Educational Institute of Ionian Islands, teiion.gr; accessed 18 June 2015.(in Greek)

- https://www.thisiszante.com/zantehotelguide

- "Trip to Zakynthos and Navagio - The Shipwreck Beach of Greece". Retrieved 20 September 2019.

General sources

- Fine, John Van Antwerp Jr. (1994) [1987]. The Late Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Late Twelfth Century to the Ottoman Conquest. Ann Arbor, Michigan: University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0472082604.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Zečević, Nada (2014). The Tocco of the Greek Realm: Nobility, Power and Migration in Latin Greece (14th–15th centuries). Belgrade: Makart. ISBN 9788691944100.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Zakynthos. |

| Wikivoyage has a travel guide for Zakynthos. |

- Science Park Zakynthos – Greek-Norwegian educational and research collaboration on Zakynthos

- Zakynthos Map

- Zante Travel Map

- The rescue of the Jews of Zakyntos during World War II

- ThisisZante.com—Tourism site