Bleecker Street

Bleecker Street is an east–west street in the New York City borough of Manhattan. It is most famous today as a Greenwich Village nightclub district. The street connects a neighborhood today popular for music venues and comedy, but which was once a major center for American bohemia. The street is named after the family name of Anthony Lispenard Bleecker, a banker, the father of Anthony Bleecker, a 19th-century writer, through whose family farm the street ran.[1]

Bleecker Street connects Abingdon Square (the intersection of Eighth Avenue and Hudson Street in the West Village) to the Bowery and East Village.

History

Bleecker Street is named by and after the Bleecker family because the street ran through the family's farm. In 1808, Anthony Lispenard Bleecker and his wife deeded to the city a major portion of the land on which Bleecker Street sits.[2]

Originally Bleecker Street extended from Bowery to Broadway, along the north side of the Bleecker farm, later as far west as Sixth Avenue. In 1829 it was joined with Herring Street, extending Bleecker Street northwest to Abingdon Square.

LeRoy Place

LeRoy Place is the former name of a block of Bleecker Street between Mercer and Greene Streets. This was where the first palatial "winged residences" were built. The effect was accomplished by making the central houses taller and closer to the street, while the other houses on the side were set back. The central buildings also had bigger, raised entrances and lantern-like roof projections. The houses were built by Isaac A. Pearson, on both sides of Bleecker Street. To set his project apart from the rest of the area, Pearson convinced the city to rename this block of the street after the prominent international trader Jacob LeRoy.[3][4][5][6]

Transportation

Bleecker Street is served by the 4, 6, <6>, B, D, F, <F>, and M trains at Bleecker Street/Broadway – Lafayette Street station. The 1 and 2 trains serve the Christopher Street – Sheridan Square station one block north of Bleecker Street.

Traffic on the street is one-way, going southeast. In early December 2007, a bicycle lane was marked on the street.

Notable places

_pg445_FLORENCE_CRITTENTON_MISSION%2C_21_BLEECKER_STREET.jpg)

Landmarks

- Bayard–Condict Building

- Bleecker Sitting Area[7] contains a sculpture by Chaim Gross and won a Village Award.[8]

- Bleecker Street Cinemas, closed in 1991

- Lynn Redgrave Theater, formerly known as Bleecker Street Theater

- The Little Red Schoolhouse, one of the nation's first progressive schools, on the corner of 6th Avenue and Bleecker Street.

- Our Lady of Pompeii Church, Carmine Street

- Overthrow, a boxing club, is located at 9 Bleecker Street, in the former home of the Youth International Party (Yippie)[9]

- Mills House No. 1 at 160 Bleecker Street was planned to be designated as an official landmark by the New York City Landmarks Preservation Commission in 1967, but the owner's lawyer objected.[10]

- The Silver Towers at 100 Bleecker Street are home to New York University faculty housing

- Washington Square Park

In addition, there are several Federal architecture-style row houses at 7 to 13 and 21 to 25 Bleecker Street; 21 and 29 Bleecker Street were also once the home of the National Florence Crittenton Mission, providing a home for "fallen women". 21 Bleecker Street's entrance now bears the lettering "Florence Night Mission," described by the New York Times in 1883 as "a row of houses of the lowest character".[11][12] The National Florence Crittenton Mission was an organization established in 1883 by Charles N. Crittenton. It attempted to reform prostitutes and unwed pregnant women through the creation of establishments where they were to live and learn skills.

The eastern-most block of Bleecker Street, in NoHo between Lafayette Street and the Bowery, is home to both the Margaret Sanger Health Center, headquarters of Planned Parenthood, and the Catholic Sheen Center, immediately adjacent to it. Bleecker Street was the original home of Sanger's original Birth Control Clinical Research Bureau, operated from another building from 1930 to 1973. Bleecker Street now features the Margaret Sanger Square, at the intersection with Mott Street. Across the street from Planned Parenthood is 21 Bleecker Street, the former home of the Florence Crittenton Mission.

Night spots

- The Bitter End at 147 Bleecker Street

- Cafe Au Go Go was in the basement of the New Andy Warhol Garrick Theatre (in the 1960s) at 152 Bleecker Street

- (Le) Poisson Rouge at 158 Bleecker Street

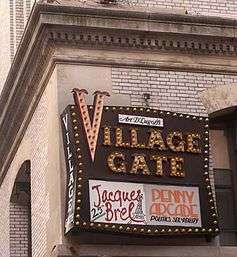

- The Village Gate was at 160 Bleecker Street

Restaurants

- John's of Bleecker Street, famous pizzeria established in 1929

- Kesté, highly rated Neapolitan style pizzeria established in 2009

- Quartino Bottega Organica, or "Quartino" for short, at 11 Bleecker Street

Former

- Music venue Cafe Wha?, where Bob Dylan, Jimi Hendrix, Bruce Springsteen, Kool & the Gang, Bill Cosby, Richard Pryor, and many others began their careers

- The CBGB club, which closed in 2006, was located at the east end of Bleecker Street, on Bowery

- Bleecker Bob's record shop started at 149 Bleecker street

Notable residents

- James Agee lived at 172 Bleecker Street, above Cafe Espanol (1941–1951)

- John Belushi lived at 376 Bleecker Street (1975)

- Mykel Board

- Robert De Niro grew up on Bleecker Street

- Robert Frank lived at 7 Bleecker Street

- Mariska Hargitay

- Alicia Keys

- Herman Melville lived at 33 Bleecker Street as a boy.[13]

- Cookie Mueller lived at 285 Bleecker Street, above Ottomanelli's (1976–1989)[14]

- Craig Rodwell lived at 350 Bleecker Street (1968–1993), from which he organized New York's first gay pride parade.[15]

- James Roosevelt at 58 Bleecker Street[16]

- Edward Thebaud

- Mark Van Doren

- Dave Winer

In popular culture

Literature

• Ted Lampron's 2019 novel BLEECKER STREET features a story-line about crime on Bleecker Street and its notorious saloons and clubs in 1890-91.

- Valenti Angelo's 1949 novel The Bells of Bleecker Street is set in the Italian American community in that neighborhood.

- Nobel laureate Derek Walcott wrote a poem about Bleecker Street entitled "Bleecker Street, Summer".

- In Marvel Comics, 177A Bleecker Street is the location of Doctor Strange's Sanctum Sanctorum.

Film and television Gangs of New York 2002 Song about Bleeker Street

- The Kate & Allie television show from the 1980s depicted two single mothers living on Bleecker in a basement apartment.

- The original Teenage Mutant Ninja Turtles movie is set on Bleecker Street according to the set designers. In one instance, it is mentioned that April's apartment is located on 11th and Bleecker.

- Much of the film No Reservations (2007), starring Catherine Zeta-Jones and Aaron Eckhart, is set in a restaurant on the corner of Bleecker and Charles Streets. The name of their fictitious restaurant is 22 Bleecker.

- In The WB series What I Like About You, Holly and Valerie live in an apartment on Bleecker Street.

- The Matthews family in Girl Meets World live near Bleecker Street and frequent the Bleecker subway station.

- New Andy Warhol Garrick Theatre (in the 1960s) at 152 Bleecker Street

- In the Friends episode "The One Where Chandler Can't Cry", an adult-video store "on Bleecker" is mentioned.[17]

Music

- Menotti wrote an opera The Saint of Bleecker Street

- Japanese pop star Ayumi Hamasaki visited Bleecker Street during recording of her (Miss)understood album. The pictures were later published in Hamasaki's famous "Deji Deji Diary" that is published in each issue of ViVi Magazine.[18]

- Iggy Pop discusses dying on Bleecker Street in his song "Punk Rocker".

- The Simon & Garfunkel album Wednesday Morning, 3 A.M. contains a song called "Bleecker Street".

- In the sea shanty "New York Girls", 44 Bleecker Street is referenced as a house of ill repute.

- "Growing Old on Bleeker Street" is a song featured on the debut album, Living Room, of pop trio AJR.

- Joni Mitchell references Bleecker Street in her 1969 album Clouds: "Still I'll take a chance and say / I found someone to love today / There's a sorrow in his eyes / Like the angel made of tin / What will happen if I try / To place another heart in him / In a Bleecker Street cafe / I found someone to love today."

- "Downtown Bleecker" is a modern instrumental jazz piece for saxophone which appears on the digital EP Midnight Sun, produced by independent artist Simon Edward.

- Lloyd Cole's eponymous 1990 album, track 2 "What do you know about love?" contains the lyrics :"it's raining on Bleecker Street, from my heart down to my feet now"

- The Marcy Playground song Vampires of New York on their debut album Marcy Playground (album) mentions "all the whores on Bleecker Street".

- Tom Paxton, in "Cindy's Crying", mentions Bleecker Street: "Cindy's cryin' but it ain't no use, She's got a habit and she can't get loose. Stoppin' each and ev'ry man she meets, Gonna be a hooker on Bleecker Street."

References

- Moscow, Henry (1978), The Street Book: An Encyclopedia of Manhattan's Street Names and Their Origins, New York: Hagstrom Company, ISBN 0823212750, p.29

- Crane, Frank W. (November 18, 1945). "Many Titles in 'Village' Area Traced Back to Old Ownerships; Admiral Warren, Who Gave Greenwich Its Name, and Aaron Burr Appear Frequently – Trinity and Rhinelanders Big Holders". Real Estate. The New York Times. p. 121.

It was Anthony Bleecker, one of the most prominent members of the family, who with his wife deeded to the city the greater part of Bleecker Street in 1808.

- Harris, Luther S. (2003). Around Washington Square : an Illustrated History of Greenwich Village. Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 83. ISBN 0-8018-7341-X.

- Burrows, Edwin G. & Wallace, Mike (1999). Gotham: A History of New York City to 1898. New York: Oxford University Press. ISBN 0-195-11634-8., p. 459

- "Changing Types of City Dwellings: Statuary Marble Mantels Indicated the Fashionable Home of Former Age" The New York Times (November 22, 1914)

- "LeRoy Place" Moving Uptown, New York Public Library exhibition

- "NYC Parks — Bleecker Sitting Area". Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- "Bleecker Street Sitting Area Renovation". GVSHP. Retrieved May 29, 2015.

- Patterson, Clayton. "OVERTHROW FANZINE" (PDF). Overthrow Boxing Club. Retrieved October 10, 2016.

- Gray, Christopher (November 6, 1994). "Streetscapes/Mills House No. 1 on Bleecker Street; A Clean, Airy 1897 Home for 1,560 Working Men". The New York Times.

- "Work Among the Fallen.; Opening the Florence Night Mission in Bleecker-Street". The New York Times. April 20, 1883.

- "A Bleecker Street home for "fallen women"". Ephemeral New York. February 3, 2010. Retrieved April 5, 2019.

- Parker, Hershel (2002). Herman Melville: A Biography. Volume II, 1851–1891. Baltimore: The Johns Hopkins University Press. p. 27. ISBN 978-0-8018-8186-2.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Curley, Mallory (2010). A Cookie Mueller Encyclopedia. Randy Press.

- Nagourney, Adam (June 25, 2000). "For Gays, a Party In Search of a Purpose; At 30, Parade Has Gone Mainstream As Movement's Goals Have Drifted". The New York Times. Retrieved January 3, 2011.

- Jim Naureckas. "Bleecker Street: New York Songlines". nysonglines.com.

- Staff. "Friends (1994-2004); Season 6, Episode 14 - The One Where Chandler Can't Cry - Full Transcript". SubsLikeScript.com. Retrieved January 13, 2019.

- "Ayumi Hamasaki". Memorial Hamasaki — DataBase pour Ayufans. Archived from the original on October 5, 2011. Retrieved June 11, 2019.