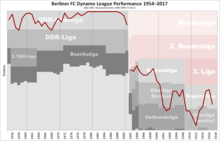

Berliner FC Dynamo

Berliner Fussball Club Dynamo e. V., commonly known as BFC Dynamo or BFC, is a German football club based in the Alt-Hohenschönhausen locality of Berlin. BFC Dynamo was formed in 1966 from the football department of SC Dynamo Berlin and was one of the key clubs of East German football. The club is the record champion of East Germany with ten consecutive league championships from 1979 through 1988. BFC Dynamo competes in the fourth tier Regionalliga Nordost.

| |||

| Full name | Berliner Fussball Club Dynamo e. V. | ||

|---|---|---|---|

| Nickname(s) | Die Weinroten (The Wine Reds) | ||

| Short name | BFC | ||

| Founded | 15 January 1966 | ||

| Ground | Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark | ||

| Capacity | 19,708 | ||

| Chairman | Norbert Uhlig | ||

| Manager | Christian Benbennek | ||

| League | Regionalliga Nordost (IV) | ||

| 2019-20 | 6th | ||

| Website | Club website | ||

|

| |||

History

Background

BFC Dynamo began as a football department of SC Dynamo Berlin, and its origins goes back to the controversial relocation of Dynamo Dresden to Berlin.

SC Dynamo Berlin was founded as a sports club in East Berlin on 1 October 1954.[1][nb 1] As all clubs bearing the name Dynamo, it was part of SV Dynamo, the Sports Association for the security agencies. The president of SV Dynamo was Erich Mielke, at the time Deputy State Secretary of the State Secretariat for State Security, commonly known as the Stasi. Erich Mielke was a huge football enthusiast, who saw football as a way of aggrandizing East Germany and socialism.[4][5]

In order to establish a competitive side in Berlin, the team of Dynamo Dresden was relocated to East Berlin in November 1954, to play for SC Dynamo Berlin. Political factors and pressure from Erich Mielke were probably the main reasons behind the relocation.[6][3][7][nb 2] The relocation was designed to provide the capital with a team that could rival Hertha BSC, Blau-Weiß 1890 Berlin and Tennis Borussia Berlin, which were still popular in East Berlin and drew football fans to West Berlin.[12][6][3][7]

Some of the players transferred from Dynamo Dresden, Johannes Matzen, Herbert Schoen and Günter Schröter, had a few years earlier been ordered to leave SG Volkspolizei Potsdam for Dresden. In Dresden they had joined the new football team SG Deutsche Volkspolizei Dresden, which replaced the popular, but bourgeois, SG Friedrichstadt. SG Deutsche Volkspolizei Dresden soon became a dominant side in East German football and was reformed as Dynamo Dresden in 1953. The city of Dresden had two sides in the DDR-Oberliga in the 1953–54 season, as BSG Rotation Dresden (then BSG Sachsenverlag Dresden) had qualified for the league in 1950. Berlin had none, and this did not please Erich Mielke.[11] Berlin was the capital of the republic, and he felt it needed a strong football team to represent it.[5]

The team finished its first league season as SC Dynamo Berlin on seventh place. It was relegated to the DDR-Liga in 1957, but immediately returned to the top level and finished the 1959 DDR-Oberliga on third place. SC Dynamo Berlin then won its first trophy in the 1959 FDGB-Pokal, defeating SC Wismut Karl-Marx-Stadt in the final. The first leg ended 0–0, but the second leg was won 3–2, with two goals scored by Christian Hofmann and one penalty goal scored by Günter Schröter.

SC Dynamo Berlin had some success in the first seasons of the 1960s, with a second place in the 1960 DDR-Oberliga season and an appearance in the 1961 FDGB-Pokal final. But SC Dynamo Berlin would find itself overshadowed in the capital by the army sponsored ASK Vorwärts Berlin, who had captured the league title in 1958 and 1960, and would go on to capture four more league titles over the coming years.[9][10] The team of SC Dynamo Berlin of the 1960s was relatively weak.[13] Their play had fallen off by 1963, and they became a lower table side. The former Dresden players had also started to age, and a second relegation to the DDR-Liga would eventually occur.[14]

A bitter dispute erupted in 1965 between SC Dynamo Berlin and SG Dynamo Schwerin, over the delegation of three players from SG Dynamo Schwerin to SC Dynamo Berlin. Local SED politicians and SV Dynamo functionaries in Schwerin wanted to transform the city into a major footballing center, and complained the reduction of SG Dynamo Schwerin into a feeder club. The disparity between SC Dynamo Berlin and SG Dynamo Schwerin was significant. The wage bill of officials and players was 315,559 Marks at SC Dynamo Berlin in the 1964–65 season, compared to 19,428 Marks at SG Dynamo Schwerin. When SC Dynamo Berlin tried to exercise its right to draw talented players from SG Dynamo Schwerin through delegation, members of the local SED Regional Administration Executive Committee and local SV Dynamo functionaries put up fierce resistance. SV Dynamo and Erich Mielke was conscious of the mass appeal of football and the role of SC Dynamo Berlin in the reputation of the Stasi.[13] The delegation was eventually canceled, but the dispute caused antipathy between the two Dynamo clubs.[15][16][17]

East German football was reorganized in the middle of the 1960s, when some football departments were made independent from their umbrella sports clubs to create ten football clubs. These ten football clubs and Dynamo Dresden were designated as focus clubs, so-called Schwerpunktclubs. They were key clubs, forming the elite of East German football. These clubs were meant to provide stability to the game at the top level and to supply the national team with talent. Promising players would be ordered to play for them. As part of this re-organization, the football department of SC Dynamo Berlin was separated from the Sports Club in 1966 and reorganized into football club Berliner FC Dynamo.[18][3][19][7] SG Dynamo Hohenschönhausen was also disbanded, and joined with BFC Dynamo. SG Dynamo Hohenschönhausen was made the reserve team of BFC Dynamo.

The football departement of SG Dynamo Hohenschönhausen had been founded in 1953 under the name SG Dynamo Berlin. After the founding of SC Dynamo Berlin, there were two associations in Berlin bearing the name "Dynamo Berlin". SG Dynamo Berlin was therefore renamed SG Dynamo Berlin-Mitte. SG Dynamo Berlin-Mitte merged with the reserve team of SC Dynamo Berlin in 1957 and reorganized into SG Dynamo Hohenschönhausen. SG Dynamo Hohenschönhausen had consisted mostly of young talents and former players of SC Dynamo Berlin.

Founding

Berliner FC Dynamo was founded on 15 January 1966. The new club was presented by Erich Mielke as the president of SV Dynamo in a ceremony before 1,600 guests in the Dynamo-Sporthalle in Hohenschönhausen in Berlin. Manfred Kirste was made club president and Erich Mielke was elected as honorary president.[20][21]

The club was formed as an elite club, and was planned to become a figurehead and flagship of East German football. The players were meant to become socialist heroes, and the team was destined to compete on European level, boosting East German self-confidence and international prestige.[22][13][23] This was to be achieved through concentration of sports performance, politically justified. Supported by Erich Mielke and SV Dynamo, BFC Dynamo would over the years be given access to the best training facilities, equipment, coaching staff and talents, but it would also be delegated some of the best players from other teams.[22]

Erich Mielke[4]

Delegation of football players and concentration of the best players in one team was common practice in East Germany, as in the Eastern Bloc.[nb 3] This was part of a sports system, where talents and the best players were concentrated in centers of excellence or delegated to elite clubs.[24][22] Focus clubs, such as BFC Dynamo, had access to talents within a designated geographical and administrative region, and permission to draw on the best players in the country.[3] But football in East Germany was also a contested sphere. Teams were relocated and frequently renamed, and players were delegated from one team to another, in accordance with political criteria, or due to machinations of powerful political leaders or interest groups at regional or central level.[25] The backing of a sponsor was crucial to the development of a team and many political leaders took interest in football and used their connections and resources to promote their favorite team and boost the prestige of their region or organization.[26][8] Dynamo Dresden was helped to remain a top club by Hans Modrow, long time SED First secretary in Bezirk Dresden, among other local politicians.[26][16] And the club also had support from Stasi Major general Horst Böhm, the Head of the Regional Administration of the Stasi in Dresden.[15][16] The favoring of BFC Dynamo was not uncontested in the East German sports political establishment, not even within SV Dynamo itself. But despite opposition, Erich Mielke would manage to ensure that some of the best players were concentrated in Hohenschönhausen.[24][22]

Beginning and rise

BFC Dynamo finished the 1966-67 season on 13th place and was relegated to the second tier DDR-Liga. A match between SG Dynamo Schwerin and BFC Dynamo in Schwerin during the 1967–68 DDR-Liga season ended with disorder among home fans. Going back to the dispute over player delegations in 1965, feelings between the two clubs had been tense. But the decisive factor causing the riots was perceived manipulation of the game by the referee. BFC Dynamo would win the match narrowly by 2–1. A Stasi investigation revealed that a sense of injustice was share also by members of the regional Stasi and that some members attending the game had either left the ground or followed the events passively.[13][17][15]

BFC Dynamo would dominate the 1967–68 DDR-Liga and immediately bounce back to the DDR-Oberliga. The club would initially struggle to reach the top of the league, before it finally captured a second place in 1971–72 season. But this period also saw Dynamo Dresden return to dominance. Dynamo Dresden had been severely weakened by the establishment of SC Dynamo Berlin in 1954 and also suffered relegation the same year. The club managed to return to the DDR-Oberliga in 1962 and won the championship in 1971. Dynamo Dresden would become one of the main rivals of BFC Dynamo, and the 1970s would largely belong to Dynamo Dresden, followed by 1. FC Magdeburg. But another rival would at the same time disappear when the Stasi outmaneuvered the army and FC Vortwärts Berlin was relocated to Frankfurt an der Oder in 1971. Erich Mielke regarded FC Vortwärts Berlin as a competitor to BFC Dynamo in the capital, while Erich Mückenberger, his fellow Politburo member and SED First Secretary in Bezirk Frankfurt, anticipated a boost for the Frankfurt and der Oder region.[2]

BFC Dynamo reached the final of the 1970–71 FDGB-Pokal, but lost 2–1 to Dynamo Dresden at the Kurt-Wabbel-Stadion in Halle. The club then made its first appearance in the European Cup Winners' Cup in the following season. BFC Dynamo reached the semi finals of the 1971–72 European Cup Winners' Cup, but was eliminated by Dynamo Moscow on a penalty shootout.

BFC Dynamo finished runners up in the 1971–72 DDR-Oberliga, and qualified for the UEFA Cup for the first time. The club reached the third round of the 1972–73 UEFA Cup, where it faced Liverpool F.C. The team managed a 0–0 draw before 20,000 spectators at the Dynamo-Stadion im Sportforum, but suffered a 3–1 defeat at Anfield, with a single goal scored by Wolf-Rüdiger Netz.[27] The club managed only a sixth place in the following two seasons, but captured a second place in the 1975–76 DDR-Oberliga season. The team qualified for the 1976–77 UEFA Cup but was eliminated by Shakhtar Donetsk in the first round.

BFC Dynamo opened the 1976-77 DDR-Oberliga season away against city rivals 1. FC Union Berlin.[28] The match was played at the Stadion der Weltjugend in front of 45,000 spectators.[29] BFC Dynamo lost the match 0–1. The return match was played on 19 February 1977 and BFC Dynamo once again lost 0–1. These two losses would be the last defeats to 1. FC Union Berlin in the East German era.[28] BFC Dynamo would come to win 19 of the next 21 matches against 1. FC Union Berlin in the DDR-Oberliga and FDGB-Pokal.[30]

Jürgen Bogs became new head coach on 1 July 1977. He had a background in the academy of BFC Dynamo and had led the junior team to a second place in the 1974 and 1976 East German junior championships (de).[31]

Dynamo Dresden would capture their third league title in a row at the end of the 1977–78 season. What happened after is subject to various rumors. Formal title celebrations took place in June 1978 at the hotel and restaurant Bastein at Prager Straße in Dresden. Erich Mielke paid a visit on behalf of SV Dynamo to congratulate the team to the title, and Dynamo Dresden player Reinhard Häfner recalls how Erich Mielke held a speech where he said that he would be happier if the BFC was champions. And according to other versions of the same event, he proclaimed that everything will be done so that in the coming year, the champion will come from Berlin, and that it was now the turn of the BFC.[32][33][34][35] But it is also rumored that Erich Mielke made a remark about bringing the title to Berlin after a fractious encounter between Dynamo Dresden and BFC Dynamo in December 1978, when he allegedly walked into the locker room of Dynamo Dresden, and told the players that "You must understand, the capital city needs a champion!".[36]

Golden era

The 1978-79 DDR-Oberliga marked a change in East German football. BFC Dynamo opened the season with ten consecutive wins and finally captured its first league title in 1979. The title was secured after a 3–1 win against Dynamo Dresden in the 24th match day in front of 22,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark.[37] The team had managed an astounding 21 wins, four draws and only one loss. Hans-Jürgen Riediger became second placed league top goal scorer with 20 goals.

During a shopping tour in the city of Gießen in Hesse after a friendly match against 1. FC Kaiserslautern on 20 mars 1979, midfielder Lutz Eigendorf broke away from the rest of the team and defected to West Germany.[38][39] Lutz Eigendorf was one of the most promising players in East German football.[40] He was a product of the elite Werner-Seelenbinder Sports School in East Berlin and had come through the youth academy of BFC Dynamo.[39][41] He was often called "The Beckenbauer of East Germany" and was considered the figurehead and great hope of East German football.[42] Lutz Eigendorf was nicknamed "Iron Foot" by the supporters of BFC Dynamo and was said to be one of the favorite players of Erich Mielke.[43][42] His defection was a slap in the face of the East German regime and allegedly taken personally by Erich Mielke.[42][40][44] Due to his talent and careful upbringing at BFC Dynamo, it was considered a personal defeat of Erich Mielke.[41] Afterwards, his name would disappear from all statistics and annals of East German football.[43] All fan merchandise with the name or image of Lutz Eigendorf were also removed from the market.[40] Lutz Eigendorf would later die in mysterious circumstances in Braunschweig in 1983.[39][45]

Winning the league title in the 1978-79 season, BFC Dynamo qualified for its first appearance in the European Cup. BFC Dynamo eliminated Ruch Chorzów and Servette FC in the first two rounds of the 1979-80 European Cup. The team reached the quarter finals, where it faced Nottingham Forest led by Brian Clough. BFC won the first leg 1–0 away, with a single goal scored by Hans-Jürgen Riediger, but was eliminated on aggregate goals, after a 1–3 loss in front ot 30,000 spectators at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Sportpark.[46] Nottingham Forest would later go on and become champions. The win against Nottingham Forest away, made BFC Dynamo the first German team to defeat an English team in England in the European Cup.

The success continued and BFC Dynamo won the league also in the following years. BFC Dynamo was set for a prestigious encounter with the West German champions Hamburger SV in the first round of the 1982-83 European Cup. The first leg was to be played at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn Sportpark and many fans were looking forward towards the match. But fearing riots, political demonstrations and spectators expressing sympathies for West German football stars such as Felix Magath, the Stasi imposed restrictions on ticket sales. Only 2,000 tickets were allowed for carefully selected fans. Most seats were instead allocated to Stasi employees, Volkspolizei officers and SED functionaries.[47][48][49] BFC Dynamo managed a draw, but was eliminated after a 0–2 loss in Hamburg.

The players of BFC Dynamo had political training and were held under a strict discipline, demanding both political reliability, obedience and a moral lifestyle. No contacts with the West was allowed.[50][51][52] The players were also under surveillance by the Stasi. They would have their telephones tapped, their rooms at training camps tapped and be accompanied by personnel from the Stasi during international trips.[53] The Ministry of Interior and the Stasi had employees integrated in the club and it is likely that some individual players were recruited as informants, so called Unofficial collaborators (IM), with the task of collecting information about other players.[54][53] During an away trip to Belgrade for a match against Partizan Belgrade in the 1983-84 European Cup, players Falko Götz and Dirk Schlegel defected to West Germany. With help from the West German Consulate general in Zagreb, they received false passports and managed to escape to Munich.[55][56][57][58] East German state news agency ADN reported that Falko Götz and Dirk Schlegen had been "wooed by West German managers with large sums of money" and "betrayed their team".[57] Although Falko Götz and Dirk Schlegen were labeled as "sports traitors", their defection had little effect on the team. According to Christian Backs, the team only received more political training, and there were no reprisals.[50] However, the loss of two regular players before the match against Partizan Belgrade was a challenge. Head coach Jürgen Bogs decided to give then 18-year old Andreas Thom a chance to make his international debut, in replacement of Falko Götz. Andreas Thom would make a terrific debut.[57][56]

BFC Dynamo had a run of 36 league matches without defeat in 1982–1984, including the entire 1982-83 season. Only after one and a half years of dominance did FC Karl Marx Stadt manage to defeat the team in the seventh match day of the 1983-84 season. The last defeat had occurred against Dynamo Dresden in the 22nd match day of the 1981–82 season. Rainer Ernst became league top goalscorer in the 1983–84 and 1984-85 DDR-Oberliga seasons. BFC Dynamo managed to score 90 goals in total during the 1984-85 season, which stands as a record for the DDR-Oberliga.

BFC Dynamo had the best material conditions in the league and the best team by far.[59] But in the league, there had been controversial refereeing decisions in favor of BFC Dynamo, which gave rise to speculations that the dominance of BFC Dynamo was not solely due to athletic performance, but also due to match-fixing.[7] However, allegations of referee bias was nothing new in East German football, and was not isolated to matches involving BFC Dynamo. Alleged referee bias as a source of unrest was a thread that ran from the very first matches of the DDR-Oberliga, and had caused unrest already back in 1950, when ZSG Horch Zwickau defeated SG Dresden-Friedrichstadt 5–1 in a match which decided the title in the 1949–50 DDR-Oberliga. Another example occurred in 1960, when ASK Vorwärts Berlin defeated SC Chemie Halle away in Halle.[60][61][62] German sports historian Hanns Leske claims that referees throughout the history of East German football had a preference for the teams sponsored by the armed and security forces.[62]

BFC Dynamo and its predecessor, SC Dynamo Berlin, was deeply unpopular in Dresden since the controversial relocation of Dynamo Dresden in 1954.[63] And the club came to be widely disliked and even hated around the country for its privileges, and for being a representative of the capital and the Stasi. Because of this, BFC Dynamo was viewed with more suspicion than affection.[64][7] The sense that BFC Dynamo benefited from referee bias did not, as popularly believed, arise first after 1978. It had already existed for years, as shown by the riots among fans of SG Dynamo Schwerin during a match between the two teams in 1968. The disapproval was kept in check as long as the club was relatively unsuccessful, but complaints increased and feelings became inflamed as the club grew successful.[65][66] A turning point was the fractious encounter between BFC Dynamo and Dynamo Dresden in Dresden in December 1978, which ended with unrest at the Rudolf-Harbig-Stadion, with 35 to 38 fans of both teams arrested. BFC Dynamo won the match 2–1. Hans Modrow, then SED First secretary in Bezirk Dresden, blamed the unrest on "inept officiating", and there were accusations from Dresden that manipulation of the match was "yet another form of discrimination against the city".[65][67][63]

The privileges of BFC Dynamo and its overbearing success in the 1980s made fans of opposing teams easily aroused as to what they saw as manipulation by bent referees, especially in Saxon cities such as Dresden and Leipzig.[65] Petitions to authorities were written by citizens, fans of other teams and local members of the SED, claiming referee bias and outright match fixing in favor of BFC Dynamo.[65][68] Animosity towards the club had been growing since its first league titles.[69][70] The team was met at away matches with aggression and shouts such as "Bent champions!" or ”Stasi swine!”.[63][70] Fans of BFC Dynamo would even be taunted by fans of opposing teams with "Jews Berlin!".[69][71][43]

Complaints due to alleged referee bias accumulated in the mid-1980s.[59] As a consequence the German Football Association of the GDR (DFV), under its General Secretary Karl Zimmermann, commissioned a secret study on the problems with referee performance and behavior in relation to the matches involving BFC Dynamo, Dynamo Dresden and 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig in the 1984–85 season.[59][72][73][nb 4] The study came to the conclusion that BFC Dynamo was favored and had gained at least 8 points due to alleged referee bias.[72][74][75] The study found several referees that had allegedly favored BFC Dynamo in matches.[73] The study found a direct advantage of BFC Dynamo in ten matches and a disadvantage of its two closest competitors, Dynamo Dresden and 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig, in eight matches together.[62][59] The study showed that 45 yellow cards had been handed out to Dynamo Dresden and 36 to 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig, compared to 16 yellow cards for BFC Dynamo, and that yellow cards had been handed out to key players in Dynamo Dresden and 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig prior matches against BFC Dynamo, so that they were banned from the next match.[76][59] The scandal surrounding alleged referee bias in East German football had now so undermined the credibility of the national competitions, that Egon Krenz, Rudolf Hellmann and the DFV under Karl Zimmermann were forced to restructure the referee commission and impose penalties on referees for poor performance.[65] As a result of the study, referees Adolf Prokop and Klaus-Dieter Stenzel received a ban from refereeing internationally. And several referees, including Adolf Prokop and Klaus-Dieter Stenze, were no longer allowed to referee matches involving BFC Dynamo.[73][75] A special review was also made of the final between BFC Dynamo and Dynamo Dresden in the 1984–85 FDGB-Pokal.[75] As a result of the review, referee Manfred Roßner received a one-year ban from refereeing matches above second tier.[77][75][78]

The controversies peaked during the match between 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig and BFC Dynamo on 22 March 1986, which practically decided the 1985-86 DDR-Oberliga season.[79] 1. FC Lokomotive Leipzig led the match 1-0 into extra time, when BFC Dynamo was awarded a penalty by referee Bernd Stumpf in the 94th minute. Frank Pastor converted the penalty and equalized. The episode, which was later known as "The shameful penalty of Leipzig", caused a wave of protests.[72][7] The DFV, under Karl Zimmerman, took action and Bernd Stumpf received a lifetime ban from refereeing. Two SV Dynamo representatives in the referee commission were also replaced. The sanctions against Bernd Stumpf were approved by Erich Honecker.[80][72][62] However, a video recording was sent to Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk (MDR) in 2000. The video recording had been filmed by BFC Dynamo for training purposes and showed the situation from a different angle. The video recording showed that decision by Bernd Stumpf was correct and that the sanctions against him were unjustified.[81][43]

It was later known that Adolf Prokop had been a Stasi officer, employed as an officer in special service (OibE), and that several referees, including Bernd Stumpf, had been Stasi informants.[75][82][26] But there is no proof that referees stood under direct orders from Stasi and no document has been found in the archives that gave the Stasi a mandate to bribe referees.[26][83][79][67] The benefit of controlling important matches in Western Europe, gift to wives and other forms of patronage, might have put indirect pressure on referees to take preventative action, in so called pre-emptive obedience.[79][83][64][84][62] In order to pursue an international career, a referee would need a travel permit, confirmed by the Stasi.[62][73][85] The German Football Association (DFB) has concluded that "it emerged after the political transition that Dynamo, as the favorite club of Stasi chief Erich Mielke, received many benefits and in case of doubt, mild pressure was applied in its favor".[86]

The picture that the success of BFC Dynamo relied upon referee bias has been challenged by ex-coach Jürgen Bogs, ex-goalkeeper Bodo Rudwaleit and others associated with the club. Some of them admit that there might have been cases of referee bias. But they insist that it was the thoroughness of their youth work and the quality of their play that earned them their titles.[78][7] In an interview with CNN, Jörn Lenz said: "Maybe we had a small bonus in the back of referees' minds, in terms of them taking decisions in a more relaxed way in some situations than if they'd been somewhere else, but one can't say it was all manipulated. You can't manipulate 10 league titles. We had the best team in terms of skill, fitness and mentality. We had exceptional players".[22]

Although speculations on manipulation in favor of BFC Dynamo could never be completely eliminated, it is a fact that BFC Dynamo achieved its sporting success much on the basis of its successful youth work, which is still recognized today.[87][67][23] Its top performers of the 1980s came mainly from its own academy and junior teams, such as Andreas Thom, Frank Rohde, Rainer Ernst, Bernd Schulz, Christian Backs and Bodo Rudwaleit. These players would influence the team for years. The only major transfers to BFC Dynamo from other clubs during its most successful period, were Frank Pastor from then relegated HFC Chemie in 1984 and Thomas Doll from then relegated Hansa Rostock in 1986.[24] These transfers would often be labeled delegations by fans of other teams, but Thomas Doll left Hansa Rostock to ensure a chance to play for the national team, and had the opportunity to choose between BFC Dynamo and Dynamo Dresden, but wanted to go to Berlin to be able to stay close to his family and because he already knew players in BFC Dynamo from the national youth teams.[88]

BFC Dynamo won its tenth league title in a row in the 1987–88 season. The club also reached the final of the 1987–88 FDGB-Pokal and defeated Carl Zeiss Jena 2–0 in front of 40,000 spectators at the Stadion der Weltjugend, securing the double and winning its first cup title since SC Dynamo Berlin captured the title in 1959. The duo Andreas Thom and Thomas Doll, paired with sweeper Frank Rohde, were one of the most effective goal scorers in the late 1980s of East German football. Andreas Thom became league top goalscorer during the 1987–88 season.

The club was drawn against West German champions Werder Bremen in the first round of 1988–89 European Cup. BFC Dynamo won a surprising 3–0 victory home at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark in the first leg, but was eliminated after an equally surprising 5–0 loss in Bremen. The return match would be known in West Germany as the "Second miracle at the Weser".

Average home attendance fell from 15,000 to 9,000 during the 1980s.[59] Many fans grew disillusioned by the alleged Stasi involvement. Notably aggravating were the restrictions on tickets sales imposed by the Stasi at international matches, were only a small number of tickets were allowed for ordinary fans, with the vast majority instead allocated to a politically handpicked audience.[89] BFC Dynamo saw the emergence of a well organized hooligan scene during the 1980s, which came to be increasingly associated with skinheads and far-right tendencies in the middle of the 1980s.[69][7][43]

BFC Dynamo saw a decline in the 1988-89 DDR-Oberliga season and finished runners-up behind Dynamo Dresden. The team defeated FC Karl Marx Stadt 1–0 in the final of the 1988–89 FDGB-Pokal and secured its third cup title. As cup winners, BFC Dynamo was set to play the DFV-Supercup against league champions Dynamo Dresden. Jürgen Bogs was removed as head coach after the 1988–89 season, and replaced by Helmut Jäschke, who had previously served as head coach of the reserve team. The DFV-Supercup was played on 5 August 1989 at the Stadion der Freundschaft in Cottbus. BFC Dynamo defeated Dynamo Dresden 4–1, with two goals scored by Thomas Doll, and won the title.

Post-unification (1990-2004)

Starting with Andreas Thom being transferred to Bayer Leverkusen in December 1989, BFC Dynamo lost its best players to West German sides in the course of 1990–91. In 1990, the side was renamed FC Berlin in an attempt to distance it from its past. In the early 1990s a number of Dynamo clubs across East Germany, such as the professional ice hockey club SC Dynamo Berlin (today Eisbären Berlin) in 1992, eliminated its Dynamo names. However, due to the supporters' desire, in 1999 the club again took up its traditional name BFC Dynamo. Having lost financial and political support as well as its best players, the side fell to tier III play and later to IV or V division leagues. BFC Dynamo had to file for insolvency in 2001 but was eventually rescued by its supporters. The insolvency proceedings were successfully closed in 2004.

Since 2004

Following its insolvency, BFC recovered to win the Verbandsliga Berlin (V) championship in 2004 and return to fourth division play in the Oberliga Nordost-Nord (IV, now V) where they settled in as upper-table side.

On 12 June 2013, BFC Dynamo won the Berlin Cup (Berlin Pokal) for a third time, beating SV Lichtenberg 47 1–0, thus qualifying for the national cup of the DFB, the DFB-Pokal.[90] The crowd of 6,381 set a new record for a Berlin Cup final.

The subsequent DFB-Pokal match against VfB Stuttgart took place on 4 August 2013 in front of 9,227 spectators. The stadium capacity of the Friedrich Ludwig Jahn Sportpark had been limited and ticket prices had been increased due to requirements by the DFB. While Dynamo's Christoph Köhne came close after hitting the inner post in the 31st minute, Vedad Ibišević won the game for Stuttgart with goals in the 40th and 75th minutes (a penalty), resulting in a 0–2 defeat.

In the 2013–14 Oberliga season, BFC Dynamo won 15 out of the initial 16 games (while drawing against SV Lichtenberg 47). After 21 season matches, the streak was extended to 20 wins and one draw, effectively securing promotion to Regionalliga Nordost with a 25-point lead.[91] The club subsequently extended contracts with its key players and announced to move back to the Friedrich Ludwig Jahn Sportpark for its Regionalliga matches starting with the 2014–15 season.[92]

Following promotion, BFC Dynamo finished the 2014–15 Regionalliga season in fifth place. During the season, coach Volkan Uluc was replaced by former Hamburger SV player and coach of SSV Jahn Regensburg, Thomas Stratos. Under Stratos, BFC Dynamo secured yet another Berlin Cup trophy, thus qualifying again for the DFB-Pokal. The crowd of 6,914 spectators during the 2015 cup final against Tasmania Berlin (1–0 victory) at the Friedrich Ludwig Jahn Sportpark set another record for a Berlin Cup final.

The 2014–15 season marked the return of the club to live television (the DFB-Pokal cup matches against 1. FC Kaiserslautern in 2011 and VfB Stuttgart in 2013 were shown by German pay TV) with its Regionalliga matches against Carl Zeiss Jena and 1. FC Magdeburg being broadcast by Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk television.

The 2015 DFB-Pokal match was lost 0:2 against 2. Bundesliga side FSV Frankfurt. Rockenbach da Silva missed a penalty for BFC.[93]

René Rydlewicz, a former Bundesliga player who had started his career at the club, took over as BFC coach in May 2016. The Regionalliga seasons 2015–16 and 2016–17 brought mixed results. However, BFC secured another Berlin Cup trophy in 2017, thus qualifying for DFB-Pokal season 2017–18. FC Schalke 04 was drawn as first-round opponent for the match scheduled 14 August 2017. 14,117 spectators watched a 0–2 loss against Schalke 04.

BFC Dynamo finished the Regionalliga season 2017–18 4th and once again qualified for the DFB-Pokal. The club was drawn to play 1. FC Köln in the first round. Due to the loss of key players such as Kai Pröger, Denis Srbeny and Rufat Dadashov in 2017 and 2018 the BFC squad was significantly weakened and eventually lost 1–9.

In January 2019, Matthias Maucksch replaced coach René Rydlewicz but stepped down after the end of the 2018–19 season. He was replaced by Christian Benbennek.

Stadiums

The training ground of the club is the Sportforum Hohenschönhausen. Its outdoor stadium has a capacity of 10,000 spectators, including 2,000 seated, and is part of a large sports complex with facilities for ice hockey, speed skating, athletics, and cycling. When opened it offered the world's first covered indoor speed skating oval. It is also the training ground for the Eisbären Berlin professional ice hockey team, formerly SC Dynamo Berlin.

The team played most European Cup matches and most seasons (1971–1992) at the Friedrich Ludwig Jahn Sportpark in Prenzlauer Berg, close to the former Berlin Wall. Following the 2014 promotion to Regionalliga Nordost, BFC moved permanently back to the Prenzlauer Berg stadium, next to the Mauerpark.[94] The stadium currently has a capacity of 19,708 spectators.

The Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark is under planning for a complete redevelopment. The estimated cost for the redevelopment of the whole area is estimated at up to €170 million, including €85 million for a new stadium. According to planning, the current stadium will be demolished after the 2019/2020 season.[95]

The Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark.

The Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark.

Supporters

East German era

BFC Dynamo played only a minor role in football in Berlin until the relocation of FC Vorwärts Berlin to Frankfurt an der Oder in 1971.[96] The club initially had modest support. But with its growing successes in the 1970s, the club began to attract young fans, primarily from the central areas around the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark, such as Prenzlauer Berg and Mitte.[7] One of the first big supporter groups of BFC Dynamo was Black Eagles. The fan club was founded in 1972 and was one of the earliest fan clubs in East German football. Fans of BFC Dynamo were the first to sew their embroidered fan club badges on their jackets. This was a novelty among football supporters in East Germany in the 1970s.[97]

The supporter scene became a focal point for various subcultures in the late 1970s and beginning of the 1980s.[98][99][100] There were punks, rockers, hippies and a few early skinheads.[98][96][101][102][49] Some were left-leaning and others were right-leaning.[98][102] Football and stadium life offered free spaces that were difficult for the authorities to control.[49] For some fans, being part of the supporter scene was an opportunity to rebel against the East German regime.[98] Most supporters of BFC Dynamo had little to do with the state. It was more important for them to protest, do their own thing and break out from everyday life.[96] Despite cheering for a club connected to the Stasi, supporters of BFC Dynamo were not true to the line.[98] Many active fans in the 1980s were against the regime.[71][102]

- A fan of BFC Dynamo in the 1980s[103]

Young people were gradually attracted by the provocative image of the club: its reputation as a Stasi club, its successes and the hatred of opposing fans.[99][100] Some fans of BFC Dynamo found delight in the unpopularity of their club and took pride in the hatred they met.[102][104][105] One fan recalled that that 1980s "were my greatest years, as we always had glorious success in provoking other fans" and another one that "we were really hated by everyone".[104] Fans of BFC Dynamo would sometimes respond to the hatred by singing chants in praise of Erich Mielke as a provocation.[15] Occasionally, they threw bananas, that were only available in East Berlin, at home fans during away matches in Saxony.[43][101]

BFC Dynamo came to be associated with areas such as Prenzlauer Berg, Pankow, Weißensee, Hohenschönhausen and certain cafés and restaurants in vicinity of Alexanderplatz.[106] The supporter scene included groups such as Black Eagles, Norbert Trieloff, Bobbys, Iron Fist, Die Ratten and Berliner Wölfe in the 1980s. Fashion played a big role in the BFC Dynamo supporter scene.[105][102]

Football related violence spread in East Germany spread in the 1970s.[49][107] The supporter scene of BFC Dynamo was still young, while clubs such 1. FC Union Berlin and BSG Chemie Leipzig had large followings.[105] A trip to Leipzig or Dresden was a difficult task.[96] Supporters of BFC Dynamo responded to the hostile environment, and learned to compensate their smaller numbers, by being more aggressive and better organized.[108][7][105][109] One fan of BFC Dynamo recalled: "There was a lot of buzz at away trips, and only then you felt your own strength. When we went with 200 people against 1,000 Unioners and you noticed: If you stick together, you have insane violence."[110] Supporters of BFC Dynamo would eventually gain a reputation for being particularly violent and organized.[7] One fan of 1. FC Union Berlin recalled: "There was hardly an enemy mob against us, we were just too many. But the people who stood in the way of the violence-seeking BFC:ers were very few. The BFC:ers were completely organized. These hundred and fifty people, everyone knew each other. They stood as a block like a wall." [111] A saying among the supporters of BFC Dynamo was "We are few, but awesome!".[105]

The development in the supporter scene would eventually catch the attention of the authorities. The Stasi assigned a group of two full-time officers from the district administration to the supporter scene during 1982-83 season.[112] From then, supporters were accompanied, observed and documented.[113] This was a measure that had previously also been applied to the supporter scene of 1. FC Union Berlin.[43] The authorities had allegedly been particularly alarmed when supporters of BFC Dynamo unfurled a poster in memory of Lutz Eigendorf with the text "Iron Foot, we mourn you!" during a match at the Friedrich-Ludwig-Jahn-Sportpark in April 1983.[114][113][7] Supporters had also started a fan club in hounour of Lutz Eigendorf.[101] The Stasi would try to control the supporter scene with a broad catalogue of measures: persistent talks, intimidation attempts, reporting requirements and arrests.[96][98] It would also attempt to infiltrate the fan clubs by unofficial collaborators (IM).[112] All football fan clubs in East Germany had to undergo registration.[49] According to Stasi information, BFC Dynamo had six registered fan clubs and 22 unauthorized fan clubs in 1986. Unauthorized fan clubs were those that were unregistered or did not meet DFV guidelines.[115]

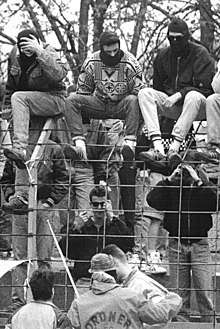

The dislike against BFC Dynamo in stadiums around the country and the hatred of opposing fans welded its supporters together.[116] A unique hooligan scene with groups, structures and training rooms would emerge at the end of the 1980s.[109] A group of 500 hooligans of BFC Dynamo raided a gas station in Jena and attacked the Volkspolizei in connection to an away match in November 1989.[117][118] The disorder at the stadium would not cease and the match was eventually abandoned.[105] The riots in Jena caught rare attention by East German state media, which until then had been relatively silent about football related disorder.[105][98]

The supporter scene of BFC Dynamo came to be increasingly associated with skinheads and far-right tendencies from the mid-1980s.[7] More and more supporters of BFC Dynamo began to embrace skinhead fashion in the early 1980s.[98][96] Skinhead fashion was now considered the most provocative outfit.[98] By the mid-1980s, the club had become particularly popular in the growing skinhead movement.[105] The reputation of BFC Dynamo as the hated Stasi club attracted skinheads, who used the club as a stage for their provocations.[99] Nationalist chants and Nazi slogans were considered the most challenging provocations, as anti-fascism was state doctrine and Nazism officially did not exist in East Germany.[119][49][7][98][120][121] For young people, being a Nazi was sometimes considered the sharpest form of opposition.[122] One fan of BFC Dynamo said: "None of us really knew anything about politics. But to raise your arm in front of the Volkspolizei was a real kick. You did that and for some of them, their whole world just fell apart".[123][96][7] A network of far-right skinhead and hooligan groups would form around the club in the late 1980s.[122]

German reunification and hooliganism

Stadium attendance collapsed in 1990. Average attendance had dropped from 8,385 in the 1988-89 season to 1,076 in the 1990-91 season.[124][125][126] Many supporter stopped attending matches after the Peaceful revolution, as the best players were sold off to clubs in West Germany, sports performance slumped, tickets prices rose, mass unemployment spread and hooligans had come to dominate the stands.[43][127][121][128] Some shifted their focus to ice hockey instead.[129] Only young supporters remained in the stadium in the beginning of the 1990s.[43] The average league attendance of the 1990-91 DDR-Oberliga was by far the lowest in the league history.[127]

Hooligans who had left East Germany for different reasons in recent years returned to East Berlin after the opening of the Berlin Wall and rejoined the hooligan scene.[130][131] Some were former skinheads who had been deported by the Stasi to West Germany in the late 1980s. Now they chanted "Mielke, we love you!" and "Who should be our Führer? Erich Mielke!" as a provocative fun, to the dismay of the club.[130][132] Supporters who returned from West Germany also brought back a new fashion based on designer clothing labels and expensive sportswear, which was adopted by the supporter scene.[130][116] While combat boots and bomber jackets were now common at many places in East Germany, some supporters of BFC Dynamo wanted to differentiate themselves. Expensive sneakers was now the new fashion.[96][131]

A wave of football hooliganism swept through East Germany in 1990.[43] The collapse of the East German regime resulted in a security vacuum.[133][127][134] The Volkspolizei was overwhelmed by the amount of disorder and often reluctant to use enough force, due to the political situation.[43][132][135] Supporters of FC Berlin, the name of BFC Dynamo since February 1990, rioted in central Jena before an away match against FC Carl Zeiss Jena in April 1990. They raided shops, smashed police vehicles with stones and left a trail of destruction in the city center.[136] Hooligans of FC Berlin armed with sticks stormed the home block during a match against 1. FC Union Berlin at the Stadion an der Alten Försterei in September 1990.[137]

The situation peaked during a match between FC Sachsen Leipzig and FC Berlin on 3 November 1990. Supporters of FC Berlin travelled in large numbers to Leipzig for the match.[134] There were clashes at the Leipzig main railway station, with one police officer injured and 50 hooligans taken into custody.[135][138] A first group of around 100 supporters of FC Berlin entered the Georg-Schwarz-Sportpark in time for kick-off.[134] Supporters of both teams tried to attack each other in the stadium and the Volkspolizei had difficulties in maintaining a buffer zone.[135] A second group of around 400 supporters of FC Berlin arrived later at the nearby Leipzig-Leutzsch S-Bahn station.[134][135] Fireworks were fired as they made their way to the stadium.[139] The group was blocked from entering the stadium by police equipped with helmets and shields, despite showing valid tickets.[140][141][130] They were then pushed back by the police using tear gas and truncheons.[134][135][140] The group returned to the S-Bahn station and made an attempt to reach the stadium from the Pettenkofer Straße instead.[134] They were again blocked by police who immediately used truncheons.[134][139]

Riots broke out at the S-Bahn station.[134] The station building was vandalized and numerous cars were smashed or burned, including at least one W 50 police truck and one police car.[134][135][139][138] The police was allegedly outnumbered, although the high number of supporters of FC Berlin at the scene claimed by the police has been disputed.[139] Cobblestones were thrown at the police waiting at the Pettenkofer Straße.[134] The Volkpolizei now decided to use their firearms.[134] 18-year old supporter Mike Polley (de) from the locality of Malchow in Berlin was hit by several bullets and instantly killed.[130][131] Several others were injured and at least another three people were seriously injured.[127][135][140] One supporter of FC Berlin was hit in the head and suffered critical injuries, but survived.[130] Reports and sources vary on what happened on the scene and how the situation was.[135] The Volkspolizei had fired between 50 and 100 shots in a about a minute, from 11 different police pistols.[135][140] Shots had been fired from distances as long as 30–40 meters.[135][139] The Volkspolizei had also fired at fleeing supporters.[139] Not every injured had come with the supporters of FC Berlin. Also an uninvolved person was shot in the leg.[135]

After the shootings, some supporters of FC Berlin left the S-Bahn station by train.[142] Many were shaken.[139] Other wanted to take revenge.[139] A group of hooligans stopped a tram, kicked the driver out and maneuvered it down town.[130][134] Riots now continued in central Leipzig, where policed presence was low.[139] The riots in central Leipzig continued for several hours and the damage was extensive.[130][134][143] Hooligans devastated entire streets.[142] All shop windows on the Nikolaistraße opposite the main railway station were smashed.[138] There was rampage at the Park Hotel.[144][145] The ground floor of a department store on Brühl was destroyed.[145] Numerous cars were demolished and up to 31 shops were smashed and looted.[145][142][135] Hooligans clashed with transport police at the main railway station. New shots were fired by the police, but no one was injured.[142][130][135]

Mike Polley was considered a beginner in the supporter scene.[142] A demonstration against police violence with 1,000 participants was arranged in Prenzlauer Berg by supporters of FC Berlin after the match against HFC Chemie on 10 November 1990.[105][135][143] The demonstration was supported by the recently founded Fanprojekt Berlin.[135] The friendly match between East Germany and West Germany that was planned to be held on the Zentralstadion in Leipzig on 21 November 1990 was cancelled for security reasons and due to the tense situation among football supporters after the shootings.[130][135] An investigation against ten police officers was opened, but closed in April 1992.[135][143] The exact circumstances around the death of Mike Pollley were never fully clarified.[141][146] A march in memory of Mike Polley in Leipzig in 2018 was attended by 850 supporters of BFC Dynamo.[147]

Matches involving FC Berlin were all security matches and the violent faction of FC Berlin would come to shape the entire 1990-91 season.[135][130] A group of 500-600 supporters of FC Berlin travelled with a special train to Rostock for an away match against F.C. Hansa Rostock in March 1991.[130][148] The police did not manage to control the situation despite a record strong presence of more than 600 officers.[148][149] Riots broke out in central Rostock, where hooligans smashed shops, demolished cars and attacked people.[130][116][148] Supporters without tickets stormed the Ostseestadion and there were fights with supporters of F.C. Hansa Rostock around the stadium.[148] Riots at the train station after the match had to be suppressed with tear gas and water cannons.[148][130] The damage was again extensive. Up to 17 shops at the Wismarischen Straße were smashed and looted, the train station was devastated and the special train had been vandalized.[149] Two police officers were injured in the turmoil.[148]

The hooligans of FC Berlin were the most notorious for years in Germany.[43] An asylum shelter in Greifswald was attacked during an away match in Greifswald in November 1991.[118][150] This caused SV Hafen Rostock 61 to postpone its upcoming match at home against FC Berlin for security reasons.[151][150] Playing for meager audiences in regional leagues, the club became a meeting place for individuals from the Berlin far-right, hooligan and criminal underground.[121][152] One of those involved in the assault on French policeman Daniel Nivel during the 1998 FIFA World Cup had connections to the hooligan scene of BFC Dynamo.[121]

BFC Dynamo had 150 Category C-supporters in 2005.[153] The club has also attracted hooligans from outside, who are otherwise not affiliated with the club, to certain matches.[99][154][155] Polish fans of Pogoń Szczecin were allegedly linked to riots during a cup match against Berliner AK 07 in 2010.[154] BFC Dynamo had 100 Category C-supporters and 190 Category-B supporters in 2019.[156] Younger hooligans of BFC Dynamo have contacts with supporter group Kaliber 030 at Hertha BSC.[121][157]

The contemporary supporter scene

The contemporary supporter scene contains various subcultures and categories of supporters. It ranges from groups of older supporters to younger ultras.[158] Older supporters constitute an essential part of the supporter scene.[100] Many are active in the supporter group 79er.[154] The group is credited for its commitment to the club, notably the youth teams. Its members have been supporters of BFC Dynamo since the late 1970s.[96] But new groups of younger ultra-oriented supporters have been formed since the 2000s, such as Fraktion H.[154][96] The contemporary supporter scene includes groups such as 79er, Mythos BFC, Fraktion H, Piefkes, Riot Sport, Black Boys Dynamo, East Company and Ultras BFC.[100][154][152][159] The supporter scene annually arranges the Mike-Polley-Gedenkturnier, which is a football fan tournament in memory of Mike Polley.[141][160]

The supporter scene played an important part in saving the club from bankruptcy in 2001. Supporters threw parties and organized collections, made donations and travelled to countries such as Austria and Switzerland to convince creditors to accept smaller pay-offs. This remains a defining moment for older supporters.[121]

BFC Dynamo is affiliated with Fanprojekt Berlin, which is an independent organization that engages in socio-pedagogical fan work.[100][161] Fanprojekt Berlin supports young fans in various aspects of life and aims at promoting a positive supporter culture.[161] BFC Dynamo engages in active fan work and has taken measures to control violent elements, exclude known violators and to distance itself from radical supporters.[100][155][162] A large number of stadium bans has been issued since the mid-2000s.[163][155] 40 bans were issued only in 2006.[163] Far-right symbols and slogans are not tolerated by the club.[100]

A minor ultras scene has emerged since the 2010s, which has initiated campaigns such as “Brown is not Wine red” and which has also engaged in football tournaments for refugees.[152][96][162] The club has encouraged the new groups of younger fans and club management has taken a stand against racism and right-wing extremism.[164][162]

One of the most well-known books in Germany about the supporter scene of BFC Dynamo is "Der BFC ist schuld am Mauerbau: Ein stolzer Sohn des Proletariats erzählt" by German author, and fan of BFC Dynamo, Andreas Gläser (de). The book was first published in 2002 and describes the supporter scene from the late 1970s and forward. The club, its reputation and supporter scene, was also the theme of stage play "Dynamoland" by Gudrun Herrbold. The play was set up in 2007 and involved young football players from BFC Dynamo as well as Andreas Gläser.[120][99]

Musicians from German rock band Klaus Renft Combo composed a song for BFC Dynamo in 1999.[165] The song gained a certain popularity in the supporter scene. German rap musician Joe Rilla (Hagen Stoll) (de) has also dedicated a song to BFC Dynamo. The song is called "Heb die Faust Hoch (BFC Dynamo Strassenhymne)" and was released in 2008.

Rivalries

The BFC Dynamo has a rivalry with Dynamo Dresden, dating back to the 1954, and a local rivalry with 1. FC Union Berlin.

Club crest

Ownership of the BFC crest

After German re-unification many East German clubs rushed to drop the names they were bearing during the Communist era. BFC Dynamo was among the clubs to do so, becoming FC Berlin. However, like many others of these clubs they found more value and fan recognition in the names, colors and crests they had played under in East Germany, thus returning to them due to supporters' pressure and based on a members' decision.

The situation of BFC Dynamo was complicated as they had neglected to copyright their old crest. In 1999 that they no longer held title, having to share it with sports souvenir seller Peter "Pepe" Mager who laid claim to the orphaned image in March 1997. Control of the logo image has since passed to André Sommer and Rayk Bernt and their marketing firm Ra-Be GmbH through which they take ten percent of the value of all fan articles sold. Sommer and Bernt also assisted in the period following the club's insolvency in 2001. This was the cause of concern for the beleaguered football association as the pair were known to have links to the Hells Angels motorcycle club.

BFC Dynamo has been working to recover the rights to its familiar traditional crest. Several alternative crests have been developed and registered in the event that they are unsuccessful in the attempt. The disputed image continued to be used by BFC Dynamo on the first team uniforms, at its website, and in other limited contexts, but the club was still unable to fully exploit the commercial value of the logo to its benefit.[166] In 2009, in response to the problem, the club decided to introduce the current logo that abandoned the traditional stylized "D" in favor of the Berlin bear. However, the club and most of its fans identify with the traditional logo.

Championship stars controversy

In 2004, the DFB introduced the Verdiente Meistervereine – a system to honor the most successful teams in Bundesliga history awarding one star for three titles, two stars for five, and three stars for ten – allowing qualifying teams to display on their jerseys the stars they have earned. BFC Dynamo petitioned the league to have their East German titles recognized, but received no reply.[167] They eventually took matters into their own hands and emblazoned their jerseys with three stars. This caused considerable debate on the fact that the DFB did not recognize East German championships, only those championships won since the 1963 formation of the Bundesliga. The issue also affected other former East German teams including Dynamo Dresden (8 titles), Vorwärts Berlin (6), SC Wismut Karl Marx Stadt, Carl Zeiss Jena and 1. FC Magdeburg.

The DFB has since updated this practice by broadening recognition to include all national level men's competitions since 1903 (when the first recognized national championship was staged), including those of the former East Germany, as well as all women's competitions since 1974. The DFB governs the use of championship stars and a club must have that governing body's approval before displaying any such badge.

BFC Dynamo has since used the championship star in accordance with DFB graphic standards, displaying a star bearing the number 10 in the current website design.

Players

Current squad

- As of 14 November 2019[168]

Note: Flags indicate national team as defined under FIFA eligibility rules. Players may hold more than one non-FIFA nationality.

|

|

Notable past players

Many players of BFC Dynamo of the 1970s and 1980s played for the East German national football team or the German national football team or became players or coaches in the Bundesliga.

|

|

Coaches

Current staff

| Coaching staff | |

|---|---|

| Head coach | |

| Assistant coach | |

| Medical department | |

| Physiotherapist | |

| Sport management and organisation | |

| Team manager | |

| Kit manager | |

| Kit manager | |

| Kit manager | |

| Head of Scouting | |

| Spokesperson | |

Coaches since 1966

SC Dynamo Berlin had six different head coaches until the founding of BFC Dynamo in 1966. The first head coach was Helmut Petzold, who was delegated along with the team of Dynamo Dresden to SC Dynamo Berlin and took office on 21 November 1954. Other head coaches of SC Dynamo Berlin were Istvan Orczifalvi, Fritz Bachmann, János Gyarmati and Fritz Gödicke. Fritz Bachmann served as head coach of SC Dynamo Berlin during the successful 1959 season.

| No. | Coach | Period | Notes |

|---|---|---|---|

| 1 | 1965-1966 | ||

| 2 | 1966-1967 | ||

| 3 | 1967-1969 | ||

| 4 | 1969-1971 | ||

| 5 | 1972-1973 | ||

| 6 | 1973-1977 | ||

| 7 | 1977-1989 | ||

| 8 | 1989-1990 | ||

| 9 | 1990-1990 | ||

| 10 | 1990-1993 | ||

| 11 | 1993-1995 | ||

| 12 | 1995-1996 | ||

| 13 | 1996-1998 | ||

| 14 | 1998-1998 | ||

| 15 | 1998-1999 | ||

| 16 | 1999-1999 | Temporary | |

| 17 | 1999-1999 | Temporary | |

| 18 | 1999-1999 | ||

| 19 | 1999-2001 | ||

| 20 | 2001-2002 | ||

| 21 | 2002-2003 | ||

| 22 | 2002-2004 | ||

| 23 | 2004-2005 | ||

| 24 | 2005-2005 | Co-Head coach, Temporary | |

| 24 | 2005-2005 | Co-Head coach, Temporary | |

| 25 | 2005-2005 | ||

| 26 | 2005-2005 | Co-Head coach, Temporary | |

| 26 | 2005-2005 | Co-Head coach, Temporary | |

| 27 | 2006-2006 | ||

| 28 | 2006-2006 | Co-Head coach, Player-coach, Temporary | |

| 28 | 2006-2006 | Co-Head coach, Player-coach, Temporary | |

| 29 | 2006-2007 | ||

| 30 | 2007-2007 | Co-Head coach, Player-coach, Temporary | |

| 30 | 2007-2007 | Co-Head Coach, Player-coach, Temporary | |

| 31 | 2007-2009 | ||

| 32 | 2009-2009 | ||

| 33 | 2009-2010 | ||

| 34 | 2010-2011 | ||

| 35 | 2011-2011 | ||

| 36 | 2011-2011 | ||

| 37 | 2011-2012 | ||

| 38 | 2012-2014 | ||

| 39 | 2014-2016 | ||

| 40 | 2016-2018 | ||

| 41 | 2019-2019 | ||

| 42 | 2019- |

Honours

BFC Dynamo was the most successful club in the DDR-Oberliga, winning ten championships. And those ten titles came consecutively, which is a feat no other team in East Germany has matched. The DDR-Oberliga was dissolved after the German Reunification and replaced by the Bundesliga, as East Germany joined West Germany to form the reunited Germany.

Domestic

- East German Champions

- Winners: (10) 1978–79, 1979–80, 1980–81, 1981–82, 1982–83, 1983–84, 1984–85, 1985–86, 1986–87, 1987–88 (record)

- Runners-up: (4) 1960,[lower-alpha 1] 1971–72, 1975–76, 1988–89

- FDGB-Pokal

- Winners: (3) 1959,[lower-alpha 1] 1987–88, 1988–89

- Runners-up: (6) 1961–62,[lower-alpha 1] 1970–71, 1978–78, 1981–82, 1983–84, 1984–85

- DFV-Supercup

- Winners: 1989

- Fuwo-Pokal (de)

- Runners-up: 1972[lower-alpha 2]

- DDR-Liga (II)

- Winners: 1957,[lower-alpha 1] 1967–68

- Won by SC Dynamo Berlin.

- The Fuwo-Pokal was only arranged in 1972. All teams in the 1971-72 DDR-Oberliga took part in the cup.

International

- European Cup

- European Cup Winners' Cup

- Semi-finals: 1971–72

Double

- DDR-Oberliga and FDGB-Pokal

- Winners: 1988

Regional

- NOFV-Oberliga Nord (IV/V)

- Berlin-Liga (V)

- Winners: 2003–04

- Berlin Cup (III-VII)

Youth

- East German Junior Championship (de)[lower-alpha 1]

- Winners: (4) 1960,[lower-alpha 2] 1978, 1979, 1987

- Runners-up (6): 1967, 1974, 1976, 1977, 1988, 1989

- East German Youth Championship (de)[lower-alpha 3]

- Winners: (4) 1967, 1972, 1975, 1987

- Runners-up: 1983, 1989

- East German Junior Cup (Junge Welt-Pokal) (de)[lower-alpha 1]

- Winners: (3) 1966, 1967, 1989

- East German Youth Cup (Youth FDGB-Pokal) [lower-alpha 3]

- Winners: (5) 1965,[lower-alpha 2] 1968, 1971, 1972, 1976 (record)

- Corresponds to U19 level.

- Won by SC Dynamo Berlin.

- Corresponds to U17 level.

Seasons in East Germany

| Year | Division | Level | Position |

| 1965–66 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 9th |

| 1966–67 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 13th |

| 1967–68 | DDR-Liga | II | 1st |

| 1968–69 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 10th |

| 1969–70 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 6th |

| 1970–71 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 9th |

| 1971–72 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 2nd |

| 1972–73 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 6th |

| 1973–74 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 6th |

| 1974–75 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 4th |

| 1975–76 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 2nd |

| 1976–77 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 4th |

| 1977–78 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 3rd |

| 1978–79 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1979–80 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1980–81 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1981–82 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1982–83 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1983–84 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1984–85 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1985–86 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1986–87 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1987–88 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 1st |

| 1988–89 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 2nd |

| 1989–90 | DDR-Oberliga | I | 4th |

| 1990–91 | NOFV-Oberliga | I | 11th |

Seasons since 1991

| Year | Division | Level | Position |

| 1991–92 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | III | 1st |

| 1992–93 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | III | 4th |

| 1993–94 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | III | 4th |

| 1994–95 | Regionalliga Nordost | III | 11th |

| 1995–96 | Regionalliga Nordost | III | 13th |

| 1996–97 | Regionalliga Nordost | III | 13th |

| 1997–98 | Regionalliga Nordost | III | 11th |

| 1998–99 | Regionalliga Nordost | III | 8th |

| 1999–00 | Regionalliga Nordost | III | 17th ↓ |

| 2000–01 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | IV | 1st |

| 2001–02 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | IV | 17th ↓ |

| 2002–03 | Verbandsliga Berlin | V | 3rd |

| 2003–04 | Verbandsliga Berlin | V | 1st ↑ |

| 2004–05 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | IV | 6th |

| 2005–06 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | IV | 6th |

| 2006–07 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | IV | 10th |

| 2007–08 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | IV | 5th |

| 2008–09 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | V | 2nd |

| 2009–10 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | V | 2nd |

| 2010–11 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | V | 7th |

| 2011–12 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | V | 13th |

| 2012–13 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | V | 3rd |

| 2013–14 | NOFV-Oberliga Nord | V | 1st ↑ |

| 2014–15 | Regionalliga Nordost | IV | 5th |

| 2015–16 | Regionalliga Nordost | IV | 4th |

| 2016–17 | Regionalliga Nordost | IV | 15th |

| 2017–18 | Regionalliga Nordost | IV | 4th |

| 2018–19 | Regionalliga Nordost | IV | 12th |

| 2019–20 | Regionalliga Nordost | IV | 6th |

European competitions

| Season | Competition | Round | Country | Club | Score |

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| 1971–72 | European Cup Winners' Cup | First round | Cardiff City | 1–1, 1–1, 6–5 (p) | |

| Second round | K. Beerschot V.A.C. | 3–1, 3–1 | |||

| Quarter-finals | Åtvidabergs FF | 2–0, 2–2 | |||

| Semi-finals | Dynamo Moscow | 1–1, 1–1, 1–4 (p) | |||

| 1972-73 | UEFA Cup | First round | Angers | 1–1, 2–1 | |

| Second round | Levski Sofia | 3–0, 0–2 | |||

| Third round | Liverpool | 0–0, 1–3 | |||

| 1976-77 | UEFA Cup | First round | Shakhtar Donetsk | 0–3, 1–1 | |

| 1978-79 | UEFA Cup | First round | Red Star Belgrade | 5–2, 1–4 | |

| 1979-80 | European Cup | First round | Ruch Chorzów | 4–1, 0–0 | |

| Second round | Servette | 2–1, 2–2 | |||

| Quarter-finals | Nottingham Forest | 1–0, 1–3 | |||

| 1980-81 | European Cup | First round | APOEL | 3–0, 1–2 | |

| Second round | Baník Ostrava | 0–0, 1–1 | |||

| 1981-82 | European Cup | First round | Zürich | 2–0, 1–3 | |

| Second round | Aston Villa | 1–2, 1–0 | |||

| 1982-83 | European Cup | First round | Hamburger SV | 1–1, 0–2 | |

| 1983-84 | European Cup | First round | Jeunesse Esch | 4–1, 2–0 | |

| Second round | Partizan | 2–0, 0–1 | |||

| Quarter-finals | Roma | 0–3, 2–1 | |||

| 1984-85 | European Cup | First round | Aberdeen | 1–2, 2–1, 5–4 (p) | |

| Second round | Austria Wien | 3–3, 1–2 | |||

| 1985-86 | European Cup | First round | Austria Wien | 0–2, 1–2 | |

| 1986-87 | European Cup | First round | Örgryte IS | 3–2, 4–1 | |

| Second round | Brøndby | 1–2, 1–1 | |||

| 1987-88 | European Cup | First round | Bordeaux | 0–2, 0–2 | |

| 1988-89 | European Cup | First round | Werder Bremen | 3–0, 0–5 | |

| 1989-90 | European Cup Winners' Cup | First round | Valur | 2–1, 2–1 | |

| Second round | Monaco | 0–0, 1–1 | |||

European record

| Competition | Record | ||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| G | W | D | L | Win % | |

| European Cup | 36 | 14 | 7 | 15 | 38.89 |

| UEFA Cup | 10 | 3 | 3 | 4 | 30.00 |

| UEFA Cup Winners' Cup | 12 | 5 | 7 | 0 | 41.67 |

| Total | 58 | 22 | 17 | 19 | 37.93 |

Further reading

- Bertram, Marco (2015): BFC Dynamo Fußballfibel (in German), Berlin: CULTURCON medien. ISBN 978-3-944068-38-1.

- Gläser, Andreas (2002). Der BFC ist schuld am Mauerbau: Ein stolzer Sohn des Proletariats erzählt (in German). Berlin: Aufbau Verlag. ISBN 3-7466-1861-4.

- Leske, Hanns (2004). Erich Mielke, die Stasi und das runde Leder: Der Einfluß der SED und des Ministeriums für Staatssicherheit auf den Fußballsport in der DDR (in German). Göttingen: Werkstatt. ISBN 3895334480.

- Luther, Jörn; Willmann, Frank (2003). BFC Dynamo – Der Meisterclub (in German). Berlin: Das Neue Berlin. ISBN 3-360-01227-5.

- Willmann, Frank (2007). Stadionpartisanen - Fans und Hooligans in der DDR (in German). Berlin: Neues Leben. ISBN 3355017442.

- Willmann, Frank (2008). Ultras Kutten Hooligans: Fußballfans in Ost-Berlin (in German). Berlin: Jaron Verlag. ISBN 3897735881.

Notes

- The founding of SC Dynamo Berlin was part of general re-organization of sport in East Germany in the middle of the 1950s, in which 21 Sports Clubs were set up under different Sports Associations (SV), such as SV Dynamo and SV Lokomotive, entirely separate from the older enterprise sports community system, the so called Betriebssportgemeinschaft (BSG) system. The Sports Clubs were envisioned as centers of excellence for the promotion of elite sport. Membership in any of these Sports Clubs was only possible through delegation by the appropriate Sports Association and each Sports Association was allotted a regional center, a so called Schwerpunkt, for the development of talented performers and players in the region.[2][3]

- This was not the first and last relocation of entire football teams in East Germany. Among several examples: SV Vorwärts der Kasernierten Volkspolizei (KVP) Leipzig was relocated to East Berlin in 1953 to play as SV Vorwärts der KVP Berlin (later known as ASK Vorwärts Berlin and then FC Vorwärts Berlin), which was then relocated to Frankfurt an der Oder in 1971 to play as FC Vorwärts Frankfurt.[8][3][9][10] The successful team of BSG Empor Lauter was relocated to Rostock in 1953, to play as SC Empor Rostock, which later became FC Hansa Rostock.[11]

- Examples: Five players from SG Volkspolizei Potsdam were delegated to Dresden in 1950 to play as SG Deutsche Volkspolizei Dresden, which later became Dynamo Dresden. In total, 17 players from 11 different cities had been picked to form the nucleus of SG Deutsche Volkspolizei Dresden.[6][11] Seven players from BSG Chemie Leipzig were delegated to SV Vorwärts der Kasernierten Volkspolizei (KVP) Leipzig in 1952.[6]

- DFV, 3 May 1985: "Zusammenstellung von Informationen zur Problematik mit der Schiedsrichtersleistungen und Verhaltensweisen in Zusammenhang mit den Spielen des BFC Dynamo, der SG Dynamo Dresden und dem 1. FC Lok Leipzig in der Saison 1984/85", SAPMO (BArch) DY 30/IV 2/2.039/247

References

- Grüne, Hardy (2001). Enzyklopädie des deutschen Ligafußballs 7: Vereinslexikon. Kassel: AGON Sportverlag. ISBN 3-89784-147-9.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). p. 9. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- Dennis, Mike (2007). "Behind the Wall: East German football between state and society" (PDF). German as a Foreign Language (GFL). 2007 (2): 46–73. ISSN 1470-9570. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Evans, Stephen (12 July 2014). "The secret police with its own football team". BBC News. London: British Broadcasting Corporation. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Nyari, Christian (30 January 2012). "Tyrant and Football Fanatic – Erich Mielke and Football in East Germany". bundesligafanatic.com. Archived from the original on 30 May 2019. Retrieved 18 May 2020.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). p. 8. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- Kleiner, John Paul (19 April 2013). "The Darth Vaders of East German Soccer: BFC Dynamo". The GDR Objectified (gdrobjectified.wordpress.com). Toronto: John Paul Kleiner. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). pp. 8–9. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- McCracken, Craig (15 April 2015). "Forward With Vorwärts Berlin, East Germany's Team Of The 60s – Part One". Beyond The Last Man (beyondthelastman.com). Craig McCracken. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- McCracken, Craig (21 April 2015). "Forward With Vorwärts Berlin, East Germany's Team Of The 60s – Part One". Beyond The Last Man (beyondthelastman.com). Craig McCracken. Retrieved 28 May 2020.

- Hesse-Lichtenberger, Ulrich (2003). Tor!: The Story of German Football (3rd ed.). London: WSC Books Ltd. p. 226. ISBN 095401345X.

- Pleil, Ingolf (2013). Mielke, Macht und Meisterschaft: Dynamo Dresden im Visier der Stasi (in German) (2nd ed.). Berlin: Chrisopher Links Verlag (LinksDruck GmbH). p. 16. ISBN 978-3-86153-756-4.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism – Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). p. 14. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- Kelemen, Luci (5 February 2018). Saleem, Omar (ed.). "Eleven Pigs and the secret police: the story of BFC Dynamo". These Football Times. Retrieved 16 June 2019.

- Dennis, Mike; LaPorte, Norman (2011). State and Minorities in Communist East Germany (1st ed.). New York: Berghahn Books. p. 130. ISBN 978-0-85745-195-8.

- Mike, Dennis; Grix, Jonathan (2012). Sport under Communism - Behind the East German 'Miracle' (1st ed.). Hampshire: Palgrave Macmillan (Macmillan Publishers Limited). p. 13. ISBN 978-0-230-22784-2.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 149. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- Leske, Hanns (2012). "Leistungskonzentration durch die Gründung von reinen Fußballclubs", "Hierarchie des DDR-Fußballs: Privilegierung der Schwerpunktclubs". Fußball in der DDR: Kicken im Auftrag der SED (in German) (2nd ed.). Erfurt: Landeszentrale für politische Bildung Thüringen. ISBN 978-3-937967-91-2.

- Hesse-Lichtenberger, Ulrich (2003). Tor!: The Story of German Football (3rd ed.). London: WSC Books Ltd. p. 227. ISBN 095401345X.

- Wyschek, Helmut (1999). "Erich Mielke, soll unser Führer sein". telegraph (de) (in German). Berlin: Prenzlberg Dokumentation e.V. 1999 (3). Retrieved 27 December 2019.

- "Jubiläum: BFC Dynamo wird 50 Jahre alt". B.Z. (in German). Berlin: B.Z. Ullstein GmbH. 15 January 2016. Retrieved 17 June 2019.

- Crossland, David (14 January 2016). "Dynamo Berlin: The soccer club 'owned' by the Stasi". CNN International. Atlanta: Cable News Network, Inc. Retrieved 30 May 2019.

- Kopp, Johannes (16 January 2006). "40 Jahre BFC Dynamo – "Wir sind doch sowieso die Bösen"". Spiegel Online (in German). Berlin: SPIEGEL ONLINE GmbH. Retrieved 9 June 2019.

- Veth, Manuel (27 July 2017). "Dynamo Berlin – The Rise and Long Fall of Germany's Other Record Champion". fussballstadt.com. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. pp. 53–54. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 55. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- "Europa League - Spielinfo - Europa League 1972/73, Achtelfinale - BFC Dynamo - Liverpool 0:0". Kicker Online (in German). Nuremberg: Olympia Verlag GmbH. n.d. Retrieved 6 August 2019.

- Stier, Sebastian (16 September 2010). "Zum Sieger delegiert". Der Tagesspiegel (in German). Berlin: Verlag Der Tagesspiegel GmbH. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "1. FC Union Berlin - BFC Dynamo, 1:0, Oberliga, 1976/1977 1. Spieltag". dfb.de (in German). Frankfurt am Main: Deutscher Fußball-Bund e.V. n.d. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- "BFC Dynamo » Record against 1. FC Union Berlin". worldfootball.net. Münster: HEIM:SPIEL Medien GmbH & Co. KG. n.d. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Ehlers, Stefan (2 April 2014). "'Ich weiß, wie Pokal-Spiele laufen können'". Ostsee-Zeitung (in German). Rostock: OSTSEE-ZEITUNG GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 4 January 2020.

- Pleil, Ingolf (2001). Mielke, Macht und Meisterschaft: Die "Bearbeitung" der Sportgemeinschaft Dynamo Dresden durch das MfS 1979–1989 (in German) (1st ed.). Berlin: Chrisopher Links Verlag (LinksDruck GmbH). p. 278. ISBN 3-86153-235-2.

In den Redetexten zu den folgenden BFC-Meisterfeiern verloren sich die Worten a die 'Freunde aus Dresden'. Im Jahr der Wende musste Mielke zur Meisterfeier wieder einmal an die Elbe reisen. Der volretzte DDR-Meisterteitel von Dynamo Dresden wurde auf der Bastei im Elbsandsteingebirge gefeiert. Reinhard Häfner erinnert sich: 'Mielke sagte, ihm wäre es zwar lieber, wenn die BFC Meister ist, aber da es ja auch Dynamo st, bleibt es sozysagen in der Familie, und das ist aucht gut.'

- Tomilson, Alan; Young, Christopher (2006). German Football: History, Culture, Society (1st ed.). Abingdon-on-Thames: Routlede, Taylor & Francis Group. p. 53. ISBN 0-415-35195-2.

- Klein, Daniel (11 April 2018). "Der Rivale aus Berlin". Sächsische.de (in German). Dresden: DDV Mediengruppe GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

Im Juni 1978 kam Erich Mielke nach Dresden. Es war ein nicht so angenehmer Termin für den Stasi- Chef und ersten Vorsitzender der Sportvereinigung Dynamo. Im Hotel und Restaurant Bastei auf der Prager Straße musste er den Dresdnern zur gewonnenen Meisterschaft gratulieren, was ihm als obersten Fan des BFC Dynamo schwergefallen sein dürfte. Seine Rede vor der Mannschaft war an Deutlichkeit nicht zu überbieten. 'Hört zu Genossen', begann er. 'Es ist schön, dass Ihr aus unserer Sportvereinigung nun schon zum dritten Mal in Folge den Fußballmeistertitel für Dynamo errungen habt. Herzlichen Glückwunsch, auch von mir. (…) Aber wir werden alles tun, damit im kommenden Jahr der Meister aus der Hauptstadt Berlin kommt und Ihr als Speerspitze den zweiten Platz belegen werdet.'

- "Interview: Mythos Dynamo – was steckt dahinter?". mdr.de (in German). Leipzig: Mitteldeutscher Rundfunk. 19 May 2011. Retrieved 8 June 2019.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 224. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.

- "GDR » Oberliga 1978/1979 » 24. Round » BFC Dynamo - Dynamo Dresden 3:1". worldfootball.net (in German). Münster: HEIM:SPIEL Medien GmbH & Co. KG. n.d. Retrieved 21 August 2019.

- "Der Mann, der den 'Ballack der DDR' ausforschte". Gießener Allgemeine. Gießen: Mittelhessische Druck- und Verlagshaus GmbH & Co. KG. 12 March 2009. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- "Es bleibt ein Rätsel - wieso starb Ex-FCK Profi Lutz Eigendorf?". srw.de (in German). Stuttgart: Südwestrundfunk. 4 November 2019. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- Amshove, Ralf (7 March 2018). "Der rätselhafte Tod des "Beckenbauer des Ostens"". sport.de (in German). Munster: HEIM:SPIEL Medien GmbH & Co. KG. Retrieved 17 May 2020.

- MacDougall, Alan (2014). The People's Game: Football, State and Society in East Germany (1st ed.). Cambridge: Cambridge University Press. p. 123. ISBN 978-1-107-05203-1.