Beja people

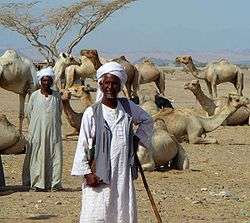

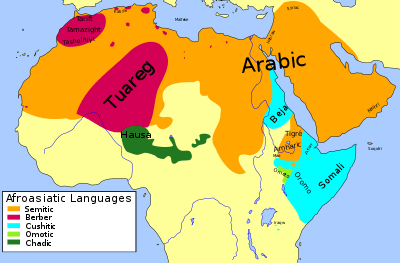

The Beja people (Beja: Oobja, Arabic: البجا, Tigre: በጃ) are an ethnic Cushitic people inhabiting Sudan, Egypt, and Eritrea. In recent history, they have lived primarily in the Eastern Desert. They number around 1,237,000 people.[1] The majority of Beja people speak the Beja language as a mother tongue, which belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afro-Asiatic family. In Eritrea and southeastern Sudan, many members of the Beni Amer grouping speak Tigre. While many secondary sources identify the Ababda as an Arabic-speaking Beja tribe due to their cultural links with the Bishaari, this is a misconception: The Ababda do not consider themselves Beja, nor are they so considered by other Beja peoples.[2]

Oobja | |

|---|---|

| |

| Total population | |

| 3,597,000 | |

| Regions with significant populations | |

| 2,371,000 | |

| 1,099,000 | |

| 127,000 | |

| Languages | |

| Beja · Sudanese Arabic · Tigre | |

| Religion | |

| Related ethnic groups | |

| Ababda · Afar · Agaw · Oromo · Saho · Somali · Tigre · other Cushitic peoples | |

History

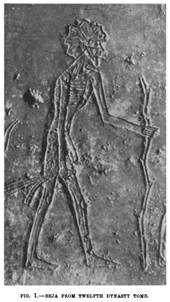

The Beja are traditionally Cushitic-speaking pastoral nomads native to northeast Africa. A geographer named Abu Nasr Mutahhar al-Maqdisi wrote in the tenth century that the Beja were at that time Christians.[3] Beja territories in the Eastern desert were made tributary by the Kingdom of Aksum in the third century.[4] The Beja were Islamized beginning in the 15th century. The now-Islamic Beja participated in the further Muslim conquest of Sudan, expanding southward. The Hadendoa Beja by the 18th century dominated much of eastern Sudan. In the Mahdist War of the 1880s to 1890s, the Beja fought on both sides, the Hadendoa siding with the rebels while the Bisharin and Amarar tribes sided with the British[5], while some Beni Amer - a subset of the Beja who live largely in modern Eritrea - sided with the Ethiopian Ras Alula in certain battles such as Kufit.[6]

The Beja Congress was formed in 1952 with the aim of pursuing regional autonomy against the government in Khartoum. Frustrated by the lack of progress, the Beja Congress joined the insurgent National Democratic Alliance in the 1990s. The Beja Congress effectively controlled a part of eastern Sudan centered on Garoura and Hamshkoraib. The Beja Congress sabotaged the oil pipeline to Port Sudan several times during 1999 and 2000. In 2003, they rejected the peace deal arranged between the Sudanese government and the Sudan People's Liberation Army, and allied with the rebel movement of the Darfur region, the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army, in January 2004. A peace agreement was signed with the government of Sudan in October 2006. In the general elections in April 2010, the Beja Congress did not win a single seat in the National Assembly in Khartoum. In anger over alleged election fraud and the slow implementation of the peace agreement, the Beja Congress in October 2011 withdrew from the agreement, and later announced an alliance with the Sudan Liberation Movement/Army.

Geography

The Beja people inhabit a general area between the Nile River and the Red Sea in Sudan, Eritrea and eastern Egypt known as the Eastern Desert. Most of them live in the Sudanese states of Red Sea around Port Sudan, River Nile, Al Qadarif and Kassala, as well as in Northern Red Sea, Gash-Barka, and Anseba Regions in Eritrea, and southeastern Egypt. There are smaller populations of other Beja ethnic groups further north into Egypt's Eastern Desert. Some Beja groups are nomadic. The Kharga Oasis in Egypt's Western Desert is home to a large number of Qamhat Bisharin who were displaced by the Aswan High Dam. Jebel Uweinat is revered by the Qamhat.

Names

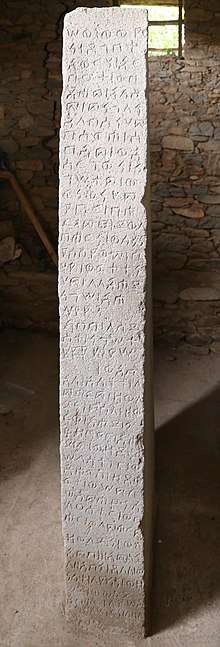

The Beja have been named "Blemmyes" in Roman times,[7] Bəga in Aksumite inscriptions in Ge'ez[8], and "Fuzzy-Wuzzy" by Rudyard Kipling. Kipling was specifically referring to the Hadendoa, who fought the British, supporting the "Mahdi," a Sudanese leader of a rebellion against the Turkish rule administered by the British.[5]

Language

The Beja speak the Beja language, known as Bidhaawyeet or Tubdhaawi in that language. It belongs to the Cushitic branch of the Afroasiatic family.[1]

The French linguist Didier Morin (2001) has made an attempt to bridge the gap between Beja and another branch of Cushitic, namely Lowland East Cushitic languages and in particular Afar and Saho, the linguistic hypothesis being historically grounded on the fact that the three languages were once geographically contiguous.[9] Most Beja speak the Beja language, but certain subgroups use other lingua franca. The Beni Amers speak a variety of Tigre, whereas most of the Halengas speak a mix of Bedawiet and Arabic.[9]

Although there is a marked Arabic influence, the Beja language is still widely spoken. The very fact that the highest moral and cultural values of this society are in one way or the other linked to their expression in Beja, that Beja poetry is still highly praised, and that the claims over the Beja land are only valid when expressed in Beja, are very strong social factors in favour of its preservation. True enough Arabic is considered as the language of modernity, but it is also very low in the scale of Beja cultural values as it is a means of transgressing social prohibitions. Beja is still the prestigious language for most of its speakers because it conforms to the ethical values of the community.[9]

Subdivisions

The Bejas are divided into clans. These lineages include the Bisharin, Hedareb, Hadendowa (or Hadendoa), the Amarar (or Amar'ar), Beni-Amer, Hallenga , Habab , Belin and Hamran, some of whom are partly mixed with Bedouins in the east.

Beja society was traditionally organized into independent kingdoms. According to Al-Yaqubi, there were six such Beja polities that existed between Aswan and Massawa during the 9th century. Among these were the Kingdom of Bazin, Kingdom of Belgin, Kingdom of Jarin, Kingdom of Nagash, Kingdom of Qita'a and Kingdom of Tankish.[10]

Genetics

According to Y-DNA analysis by Hassan et al. (2008), around 52% of Beja in Sudan carry the E1b1b haplogroup, with most belonging to the V32 subclade. The remaining Beja individuals bear the J clade (38%). Both paternal lineages are also common among local Afroasiatic-speaking populations. The next most frequent haplogroups carried by Beja are the European-associated R1b haplogroup (~5%) and the archaic African A3b2 clade (~5%).[11]

Maternally, Hassan (2009) observed that approximately 71% of their Beja samples carried various subclades of the Africa-centered macrohaplogroup L. Of these mtDNA lineages, the most frequently borne clade was L3 (35.6%), followed by the L2 (16.7%), L1 (8.3%), L0a (6.3%), L4 (2.1%) and L5 (2.1%) haplogroups. The remaining 29% of the Beja individuals belonged to sublineages of the Eurasian macrohaplogroups M (4.2% M1) and N (10.4% U6a1, 8.3% preHV1, 2.1% N/J1b, 2.1% R/T1, 2.1% R/U3).[12]

Dobon et al. (2015) identified an ancestral autosomal component of West Eurasian origin that is common to Beja individuals and other Afroasiatic-speaking populations in the Nile Valley, including Sudanese Arabs. Known as the Coptic component, it peaks among Egyptian Copts who settled in Sudan over the past two centuries. The scientists associate the Coptic component with Ancient Egyptian ancestry, without the later Arabian influence that is present among other Egyptians.[13] Hollfelder et al. (2017) also analysed various populations in Sudan and similarly observed close autosomal affinities between the examined Beja, Nubians and Sudanese Arabs, as well as between Beja individuals and Afroasiatic-speaking populations inhabiting the Horn of Africa. The Beja carried significant West Eurasian ancestry, with the scientists suggesting that this gene flow may have been derived from either early migrations from outside Africa or from contact with Cushitic-speaking populations of the Horn.[14]

See also

References

- "Bedawiyet". Ethnologue. Retrieved 14 October 2016.

- ضرار, محمّد صالح (2012). تاريخ شرق السودان. Khartoum: مكتبة التوبة. p. 36.

- Ruffini, Giovanni. "Abu Nasr Mutahhar al-Maqdisi". Medieval Nubia: A Source Book. Retrieved 19 June 2018.

- Hatke, George. "Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa". Institute for the Study of the Ancient World. New York University. Retrieved 19 June 2019.

- Orville Boyd Jenkins, Profile of the Beja people (1996, 2009).

- Wingate, Francis (1891). Mahdiism and the Egyptian Sudan: Being an Account of the Rise and Progress of Mahdiism and of Subsequent Events in the Sudan to the Present Time. London: Macmillan and Company. p. 230.

- Stanley Mayer Burstein, Ancient African Civilizations: Kush and Axum, p. 167 (2008)

- Hatke, George. "Aksum and Nubia: Warfare, Commerce, and Political Fictions in Ancient Northeast Africa". Ancient World Digital Library. NYU Press. Retrieved 29 May 2020.

- Martine Vanhove, The Beja Language Today in Sudan: The State of the Art in Linguistics 2006.

- Elzein, Intisar Soghayroun (2004). Islamic Archaeology in the Sudan. Archaeopress. p. 13. ISBN 1841716391. Retrieved 13 March 2015.

- Hassan, Hisham Y.; et al. (2008). "Y‐chromosome variation among Sudanese: Restricted gene flow, concordance with language, geography, and history". American Journal of Physical Anthropology. 137 (3): 316–323. doi:10.1002/ajpa.20876. PMID 18618658. Retrieved 11 October 2017.

- Hassan, Hisham Y. "Genetic Patterns of Y-chromosome and Mitochondrial DNA Variation, with Implications to the Peopling of the Sudan". University of Khartoum. pp. 90–92. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Begoña Dobon; et al. (28 May 2015). "The genetics of East African populations: a Nilo-Saharan component in the African genetic landscape" (PDF). Scientific Reports. 5: 9996. doi:10.1038/srep09996. PMC 4446898. PMID 26017457. Retrieved 13 November 2017.

- Hollfelder, Nina; Schlebusch, Carina M.; Günther, Torsten; Babiker, Hiba; Hassan, Hisham Y.; Jakobsson, Mattias (2017-08-24). "Northeast African genomic variation shaped by the continuity of indigenous groups and Eurasian migrations". PLOS Genetics. 13 (8): e1006976. doi:10.1371/journal.pgen.1006976. hdl:11858/00-001M-0000-002D-D3E0-F. ISSN 1553-7404. PMC 5587336. PMID 28837655.

Admixture of non-Africans into the Beni Amer was also dated to an early event about 107.7 ± 24.4 generations ago (Z = 4.41711) and a younger event, 34.2 generations ago (± 9.6, Z-score = 3.55532 Fig 3C, S7 Table) suggesting an early migration from Eurasian into these coastal African populations, possibly across the sea. However, these old admixture events into the Beni Amer could be driven by admixture from the Cushitic-speaking populations of the Horn of Africa

- A. Paul, A History of the Beja Tribes of the Sudan, Cambridge University Press, 2012.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Beja people. |