Battle of San Juan de Ulúa (1568)

The Battle of San Juan de Ulúa was a battle between English privateers and Spanish forces at San Juan de Ulúa (in modern Veracruz, Mexico). It marked the end of the campaign carried out by an English flotilla of six ships that had systematically conducted what the Spanish considered to be illegal trade in the Caribbean Sea, including the slave trade, at times imposing it by force.[2][3]

Background

Subsequent to the beginning of the Age of Discovery and the European exploration of the New World it was determined that in order to minimize potential conflict between the two major naval powers of the world at the time, Spain and Portugal, that a demarcation line between the two spheres of influence would be necessary. In the 1494 Treaty of Tordesillas, dividing the New World into Spanish and Portuguese zones was signed by the nations’ respective monarchs and Pope Alexander VI. As a result, the Spanish crown considered everything west of the Zaragoza antimeridian to be its personal property, including the entire North American continent.[4] However, subsequent to the Protestant Reformation in the early 16th century and due to the fact that the Protestant nations of Europe did not recognize Papal spiritual or temporal authority, other powers routinely ignored the treaty. English merchants and adventurers subsequently engaged in trade missions with the various Spanish posts in the New World, as well as founding their own colonies.[5] Spain was deeply suspicious of any attempt by foreign powers to trade or establish colonies in their zone of control, going so far as to massacre several hundred French Huguenot inhabitants of Fort Caroline in French Florida in 1565 after they had surrendered.

John Hawkins, an early English adventurer to the New World, had previously engaged in two other trading voyages to the Spanish colonies in contravention of the treaty, in 1562–63 and in 1564–65, with tacit approval from the English crown.[7] On each occasion Hawkins had traded slaves for gold, silver, pearls, hides, and sugar with various Spanish settlements with varying degrees of success. Despite this being illegal according to Spanish law, local governors and magistrates were nevertheless willing to trade with Hawkins provided he either proffered them with bribes or sold his merchandise at a discount. On each occasion Hawkins received written testimonials from local Spanish officials confirming his good behavior and his voyages were profitable.[8] During his second voyage, while stopping Rio de la Hacha to sell slaves, wine, flour, biscuit, and linens, he took orders from Spanish clients for his next journey and obtained a letter from the local Spanish treasurer attesting to his fair dealings. Nevertheless, the Spanish authorities were alarmed by this challenge to their monopoly and as such the court of justice in Santo Domingo ordered authorities to seize any English ships and their cargos in order to prevent further foreign incursions.

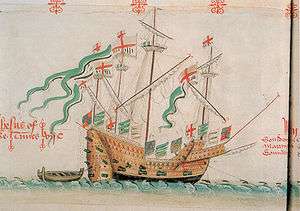

The English fleet consisted of 5 ships: the Royal carracks Jesus of Lübeck (leased from Queen Elizabeth I) under John Hawkins, the Minion under John Hampton, and the barques Judith under Hawkins' cousin Francis Drake, Angel and Swallow.[9] A captured Portuguese caravel joined the privateers near the coast of Ghana, where the English competed with Portuguese slave traders. The ship was renamed Grace of God.[10] A seventh ship, the barque William and John, sailed back home before the battle,[11] but after reaching Ireland on February 1569, she was lost with all hands on her way back to England.[12] The fleet took on water and 400-500 slaves in Guinea in early February 1568 and, reaching Dominica on March 27, 1568, Hawkins began selling his cargoes to Spanish colonists for gold, silver, and jewels, as per his previous voyages, departing from Cartagena on the 23rd of July.[13]

After attempting to penetrate the coast of Florida in August, the fleet met with a powerful storm which warped the Jesus of Lübeck’s hull planking and damaged her rudder.[13] Due to the shallow draughts along the Florida coast and unwilling to make a transatlantic voyage in such a state as well as being low on supplies, the fleet sailed for the nearest available port, San Juan de Ulua on September 16. While traveling to San Juan and concerned about being intercepted by Spanish authorities, Hawkins overtook three Spanish vessels carrying 100 passengers, hoping that with these he might be able to negotiate for a better terms to refit and resupply. Spanish officials originally mistook his fleet for an expected Spanish one and went aboard, only to discover to their dismay that they were in fact aboard an English ship.[14] Hawkins informed them that he did not seek plunder or pillage but instead wished only to secure food and water and repair his ship, at which the Spanish were relieved. But while they were carrying out this reprovisioning, a Spanish escort fleet under command of Don Francisco Luján arrived in the port the very next day, accompanying the new viceroy of New Spain, Don Martin Enriquez de Almanza, to his post in Mexico City.[15]

Battle

San Juan’s port facilities were extremely small and rudimentary, consisting of a mooring wall built by the Spanish on "a little yland of stones, not past three feet aboue water in the highest place, and not past a bow-shotte ouer any way at the most, and it standeth from the maine land, two bowshootes or more"[16] and, given the difficulties of fitting both fleets at the anchorage, Hawkins sent out a small boat to inform the Spanish that they were already in the port and that there should be conditions governing how the two fleets were to pass each other in order to avoid confrontation.[14]

The English had repeatedly ignored the Treaty of Tordesillas by attacking merchant shipping but at this point they believed the Spanish would respect a truce on this occasion. After spending two days negotiating, terms were agreed upon and a dozen hostages were exchanged, whereupon the Spanish fleet was allowed to enter the moorage. Two days were spent anchoring the Spanish ships and, for the purposes of safety, the ships of each country were anchored apart from each other. Under the conditions of the agreement the English were permitted by the Spanish to buy supplies for money, repair their ships, and occupy the island with 11 pieces of ordnance.[16] Spaniards were also forbidden from visiting the island while under arms. However, the Spanish commander of the fleet had specifically been charged with stopping English trade in New Spain and as a result, despite the truce which had been agreed upon by both parties[16] the Spanish began secretly massing an attack force on the mainland near the harbor in order to seize the shore batteries which Hawkins had manned to defend the anchorage.[14] In addition, the Spanish hid an attack force of 150-300 men on board a hulk, the San Salvador, which would be brought up between the English and Spanish ships.

According to the plan the hulk would be brought up between the Spanish and English fleets at midday on 24 September and, once in position, a trumpet would sound, signaling the attack, ideally while the English were taking their lunch.[17] The English were nevertheless immediately suspicious after spotting Spanish crews shifting weapons between ships. Suspecting that the Spanish were planning on launching an attack from the hulk, Hawkins sent the captain of the Jesus of Lübeck, Robert Barret (who spoke fluent Spanish) to demand that the viceroy disembark his men from the hulk and cease their threatening activities.[16] The viceroy, Don Martin de Enriquez, realizing that the plot had been detected, seized Barrett and ordered the trumpet to sound and the Spanish launched their attack. The Spanish troops which had been concealed on the mainland quickly rowed to the island and overwhelmed the English sailors who had been manning their cannons on the beach, with many of the sailors fleeing to the safety of the ships.[16] No quarter was given. The Minion, the ship closest to the Spanish hulk, was the immediate target of the Spanish boarding action but was able to defend itself against the attack and hauled away. The next target, Jesus of Lübeck, was boarded by the Spaniards from the hulk but after a violent struggle on board the ship, the Spaniards were repulsed and the Jesus of Lübeck was able to cut away and join the Minion.[17] The French commander of the Grace of God, Robert Blondel, set her on fire before joining Hawkins on board the Jesus of Lübeck.[18]

By this point the shore batteries were entirely in the possession of the Spaniards, who then turned the cannons against their former owners and caused great damage to the Jesus of Lübeck, demasting her, and sinking the smaller English ships.[19] The English maneuvered the Jesus of Lübeck so that it stood in-between the Minion and the shore batteries, thus acting as a shield and moored the Minion out of range of the Spanish batteries on the shore.

The early assault and capture of the island's batteries—held until then by the English—by a Spanish pinnace, commanded by a Captain Delgadillo,[20] became decisive to the fate of the English fleet.[21] Angel sank after a few salvoes, and Swallow was seized by the Spanish soldiers manning the batteries.[22] The crews of both of them, along with some members of the crew of the Jesus of Lübeck, were later rescued by a pinnace after Hawkins gave the order to abandon the ship. Hawkins took command then of the Minion.[9]

Only the Judith, commanded by Drake, and Minion escaped, whilst battle was still raging on, leaving behind them the Jesus of Lubeck and some members of her crew still on board. The surviving vessels sailed out when two ships on fire were driven on them by the Spanish. The Englishmen feared such a fire ship attack which, despite their concerns, failed to inflict any damage on the English ships.[9] During the night Francis Drake, commanding the 50-ton Judith, abandoned the fleet and sailed for home, leaving Hawkins alone on board the overcrowded and poorly provisioned 100-ton Minion.[23] During the night the wind shifted and, according to the royal lieutenant-governor in Vera Cruz Francisco de Bustamente, this prevented the Spanish from following the English.[24] The Jesus of Lübeck was eventually boarded by the Spanish party lurking inside the hulk, under the command of Captain Juan de Ubilla.[25] There are allegations that Ubilla allowed his men to loot the booty left on board the Jesus of Lübeck by Hawkins.[25] Luján's fleet lost the vice-admiral ship, the galleon Santa Clara, which burnt and sank inside the port.[26] The flagship San Pedro, the only full-armed Spanish ship at San Juan, was also badly hit during an exchange of fire with Minion.[27][28]

The abandoned crewmen

During their withdrawal, the Minion and the Judith were hopelessly overcrowded, and some of their men had to be abandoned on what is now the southern coast of the United States to save on supplies for the Atlantic crossing. Hawkins left behind 110 men to surrender to the Spanish.

Initially they were treated well by the Spanish, some were released and settled down to farming and started families. However, three years later, in 1571, the Inquisition arrived in Mexico, including the merciless Moyn de Contreras and Fernandez de Bonilla. The released crewmen were rounded up and imprisoned. The captives were brought before the Inquisition; the eleven who had been juveniles (under 16 at the time of the battle) were deemed to have been too young to have received any Catholic catechism, and so were treated relatively leniently - for example, Miles Philips, born in 1554, was sentenced to three years in a Jesuit house in Mexico.[29]

The rest were regarded as heretical lapsed Catholics, and in February 1574, after being tortured to obtain confessions, sentences were handed down, including these :-

- William Collins, of Oxford, age forty, seaman, ten years in the galleys;

- John Burton, of Bar Abbey, twenty-two, seaman, 200 lashes and six years in the galleys;

- John Williams, twenty-eight, of Cornwall, 200 lashes and eight years in the galleys;

- George Dee, thirty, seaman, 300 lashes and eight years in the galleys.

The following year John Martin of Cork, also known as Cornelius the Irishman, was burned at the stake; and some others were sentenced to penal servitude in the galleys for life.[30]

Aftermath

Hawkins eventually arrived back in England with a crew of only 15.[26] Drake had reached Plymouth one month earlier, in December 1568.[30] Only 70 or 80 sailors from the original expedition returned to England at all.[12]

While Hawkins accused the Spaniards of treason for not honouring the truce,[31] Don Enrique's intention had always been to uphold his authority and the Spanish monopoly in West Indies.[3]

For decades to come, the battle of San Juan de Ulua was remembered by Englishmen as an egregious example of Spanish treachery to be avenged.[32] Drake’s desertion with the Judith in the heat of the action and leaving his relative and patron to fend for himself would haunt Drake for years to come and helped harden Drake’s attitudes towards Catholics in general and Spaniards in particular.[32]

The battle was a clear precursor of the war that broke out between Philip II of Spain and Elizabeth I of England in 1585.[3][33]

Notes

- R. G. Grant (2017). 1001 Battles That Changed the Course of History. Book Sales. p. 279.

- Saiz Cidoncha, page 55

- Walton, Timothy R.: The Spanish Treasure Fleets. Pineapple Press Inc, 2002, page 74. ISBN 1561642614

- Bown, Stephen R. (14 February 2012). 1494: How a Family Feud in Medieval Spain Divided the World in Half. St. Martin's Press. pp. 3–5. ISBN 9781429941303. Retrieved 21 September 2018.

- Bown, pages 5–6

- Dean, James Seay (2010). Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Sea Dogs on the Spanish Main. Stroud, Gloucestershire, England: The History Press. p. 27. ISBN 9780752450964.

- Dean, page 30

- John Barrow: The life, voyages, and exploits of Admiral Sir Francis Drake.

- Lewis, Charles Lee: Famous old-world sea fighters. Ayer Publishing, 1969, page 93. ISBN 0-8369-1419-8

- Kelsey, Harry: Sir John Hawkins: Queen Elizabeth's slave trader.Yale University Press, 2003, page 104.ISBN 0300096631

- Hampdem, John: Francis Drake, privateer: contemporary narratives and documents. Taylor & Francis, 1972, page 40. ISBN 0-8173-5703-3

- Dean, page 36

- Dean, page 37

- Marley, page 64

- Hakluyt, Richard (1890). The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation. Edinburgh, Scotland: E. & G. GOLDSMID. pp. Volume 15, Part III, Chapter 2.

- Dean, page 38

- Hannay, David: The sea trader: his friends and enemies. Harper & brothers, 1912, page 197

- Dean, page 39

- Saiz Cidoncha, page 61

- Unwin, page 197

- Unwin, page 215

- Dean, page 40

- Wright, page 152

- Wright, Irene Aloha: Spanish documents concerning English voyages to the Caribbean, 1527-1568. Hakluyt Society, 1929, page 25

- Marley, page 65

- Saiz Cidoncha, page 60

- Unwin, page 201

- "The Elizabethans" by A.N. Wilson, Paperback, 464 pages; Publisher: Arrow (6 Sept. 2012); Language: English; ISBN 0099547147 ; ISBN 978-0099547143; https://www.amazon.co.uk/Elizabethans-N-Wilson/dp/0099547147

- Dean, page 41

- Hayklut, Richard: The Principal Navigations. London, 1589, page 555

- Dean, page 42

- Dawson, Ian: The Tudor century. Nelson Thornes, 1993, page 303. ISBN 0-17-435063-5

References

- Dean, James Seay: Tropics Bound: Elizabeth's Sea Dogs on the Spanish Main The History Press, 2010, ISBN 978-0-7524-5096-4

- Hakluyt, Richard: The Principal Navigations, Voyages, Traffiques, and Discoveries of the English Nation E.& G. Goldsmid, 1890

- Marley, David: Wars of the Americas: a chronology of armed conflict in the New World, 1492 to the present ABC-CLIO, 1998. ISBN 0-87436-837-5

- Unwin, Rayner: The Defeat of John Hawkins: A Biography of His Third Slaving Voyage Allen & Unwin, 1960.

- Sugden, John: Sir Francis Drake Henry Holt & Company, 1990.

- Saiz Cidoncha, Carlos: Historia de la piratería en América española Editorial San Martín, 1985. ISBN 84-7140-230-0 (in Spanish)

- Villiers, Alan: "Men, Ships, and the Sea" National Geographic Society, 1973.

- Wright, Irene Aloha: Spanish Documents Concerning English Voyages to the Caribbean, 1527-1568 Hakluyt Society, 1925