Barnacle goose

The barnacle goose (Branta leucopsis) belongs to the genus Branta of black geese, which contains species with largely black plumage, distinguishing them from the grey Anser species. Despite its superficial similarity to the brant goose, genetic analysis has shown it is an eastern derivative of the cackling goose lineage.

| Barnacle goose | |

|---|---|

| |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Chordata |

| Class: | Aves |

| Order: | Anseriformes |

| Family: | Anatidae |

| Genus: | Branta |

| Species: | B. leucopsis |

| Binomial name | |

| Branta leucopsis (Bechstein, 1803) | |

Taxonomy and naming

The barnacle goose was first classified taxonomically by Johann Matthäus Bechstein in 1803. Branta is a Latinised form of Old Norse Brandgás, "burnt (black) goose" and the specific epithet is from the Ancient Greek leukos "white", and opsis "faced".[2]

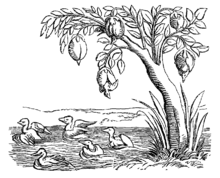

The barnacle goose and the similar brant goose were previously considered one species, and were formerly believed to spawn from the goose barnacle.[3] This gave rise to the English name of the barnacle goose and the scientific name of the brant.[2] It is sometimes claimed that the word comes from a Celtic word for "limpet", but the sense-history seems to go in the opposite direction.[4] The barnacle myth can be dated back to at least the 12th century. Gerald of Wales claimed to have seen these birds hanging down from pieces of timber, William Turner accepted the theory, and John Gerard claimed to have seen the birds emerging from their shells. The legend persisted until the end of the 18th century. In County Kerry, until relatively recently, Catholics abstaining from meat during Lent could still eat this bird because it was considered as fish.[5]

Description

The barnacle goose is a medium-sized goose, 55–70 cm (22–28 in) long,[6] with a wingspan of 130–145 cm (51–57 in) and a body mass of 1.21–2.23 kg (2.7–4.9 lb).[7][8] It has a white face and black head, neck, and upper breast. Its belly is white. The wings and its back are silver-gray with black-and-white bars that look like they are shining when the light reflects on it. During flight, a V-shaped white rump patch and the silver-gray underwing linings are visible.

Distribution

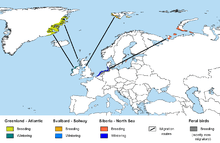

Barnacle geese breed mainly on the Arctic islands of the North Atlantic. The three main populations, with separate breeding and wintering ranges, from west to east, are:

- Breeding in eastern Greenland, wintering on the Hebrides of western Scotland and in western Ireland, population about 40,000

- Breeding on Svalbard, wintering on the Solway Firth on the England/Scotland border, population about 24,000

- Breeding on Novaya Zemlya, wintering in the Netherlands, population about 130,000

- A new fourth population, derived from the Novaya Zemlya population, has become established since 1975 breeding on the islands and coasts of the Baltic Sea (Estonia, Finland, Denmark, and Sweden), and wintering in the Netherlands. Its population numbers about 8,000.

Small numbers of feral birds, derived from escapes from zoo collections, also breed in other Northern European countries. Occasionally, a wild bird will appear in the Northeastern United States or Canada, but care must be taken to separate out wild birds from escaped individuals, as barnacle geese are popular waterfowl with collectors.

Ecology, behavior, and life history

.jpg)

.jpg)

Barnacle geese frequently build their nests high on mountain cliffs, away from predators (primarily Arctic foxes and polar bears), but also away from their feeding grounds such as lakes, rivers. Like all geese, the goslings are not fed by the adults. Instead of bringing food to the newly hatched goslings, the goslings are brought to the ground. The parents show them the way to jump from the cliff and the goslings follow them by instincts and take the plunge. Unable to fly, the goslings, in their first days of life, jump off the cliff and fall; their small size, feathery down, and very light weight helps to protect some of them from serious injury when they hit the rocks below, but many die from the impact. Arctic foxes are attracted by the noise made by the parent geese during this time, and capture many dead or injured goslings. The foxes also stalk the young as they are led by the parents to wetland feeding areas.[9] Due to these hardships only 50% of the chicks survive the first month.[10]

Conservation

The barnacle goose is one of the species to which the Agreement on the Conservation of African-Eurasian Migratory Waterbirds applies.[11] According to Sveriges ornitologiska förening, the geese began breeding in Sweden in 1971, and according to Skansen, it was 40 years ago, more or less, when the entire population of barnacle geese left in the autumn to return in spring, soon after they began breeding in the wild. The number of barnacle geese is stable to increasing.[12]

Folklore

The natural history of the barnacle goose was long surrounded with a legend claiming that they were born of driftwood:

Nature produces [Bernacae] against Nature in the most extraordinary way. They are like marsh geese but somewhat smaller. They are produced from fir timber tossed along the sea, and are at first like gum. Afterwards they hang down by their beaks as if they were a seaweed attached to the timber, and are surrounded by shells in order to grow more freely. Having thus in process of time been clothed with a strong coat of feathers, they either fall into the water or fly freely away into the air. They derived their food and growth from the sap of the wood or from the sea, by a secret and most wonderful process of alimentation. I have frequently seen, with my own eyes, more than a thousand of these small bodies of birds, hanging down on the sea-shore from one piece of timber, enclosed in their shells, and already formed. They do not breed and lay eggs like other birds, nor do they ever hatch any eggs, nor do they seem to build nests in any corner of the earth.[13]

The legend was widely repeated in, for example, Vincent of Beauvais's great encyclopedia. However, it was also criticized by other medieval authors, including Albertus Magnus.[13]

This belief may be related to the fact that these geese were never seen in summer, when they were supposedly developing underwater (they were actually breeding in remote Arctic regions) in the form of barnacles—which came to have the name "barnacle" because of this legend.

Based on these legends—indeed, the legends may have been invented for this purpose[14]—some Irish clerics considered barnacle goose flesh to be acceptable fast day food, a practice that was criticized by Giraldus Cambrensis, a Welsh author:

...Bishops and religious men (viri religiosi) in some parts of Ireland do not scruple to dine off these birds at the time of fasting, because they are not flesh nor born of flesh... But in so doing they are led into sin. For if anyone were to eat of the leg of our first parent (Adam) although he was not born of flesh, that person could not be adjudged innocent of eating meat.[13]

At the Fourth Council of the Lateran (1215), Pope Innocent III explicitly prohibited the eating of these geese during Lent, arguing that despite their unusual reproduction, they lived and fed like ducks and so were of the same nature as other birds.[15]

The question of the nature of barnacle geese also came up as a matter of Jewish dietary law in the Halakha, and Rabbeinu Tam (1100–71) determined that they were kosher (even if born of trees) and should be slaughtered following the normal prescriptions for birds.[13] In one Jewish legend, the barnacle goose is purported to have its beak forever attached to the tree from which it grew just as the Adne Sadeh is fixed to the earth by its navel cord.[16] The mythical barnacle tree, believed in the Middle Ages to have barnacles that opened to reveal geese, may have a similar origin to the other legends already mentioned.[17]

References

- BirdLife International. "Branta leucopsis". IUCN Red List of Threatened Species: e.T22679943A131909954. Retrieved 16 April 2020.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Jobling, James A (2010). The Helm Dictionary of Scientific Bird Names. London: Christopher Helm. pp. 77, 225. ISBN 978-1-4081-2501-4.

- Minogue, Kristen (29 January 2013). "Science, Superstition and the Goose Barnacle". Smithsonian Environmental Research Center. Retrieved 16 April 2020.

- "barnacle". Oxford English Dictionary (3rd ed.). Oxford University Press. September 2005. (Subscription or UK public library membership required.)

- Cocker, Mark; Mabey, Richard (2005). Birds Britannica. London: Chatto & Windus. pp. 78–80. ISBN 0-7011-6907-9.

- Soothill, Eric; Whitehead, Peter (1978). Wildfowl of the World. London: Peerage Books. ISBN 0-907408-38-9.

- Dunning, John B. Jr., ed. (1992). CRC Handbook of Avian Body Masses. CRC Press. ISBN 978-0-8493-4258-5.

- Ekin, U. (2011). "Branta leucopsis barnacle goose". Animal Diversity Web. University of Michigan Museum of Zoology. Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- Life Story (TV series)#Episodes

- Barnacle goose, Mountains, Hostile Planet

- "Waterbird species to which the Agreement applies". UNEP/AEWA (United Nations Environment Programme/African-Eurasian Waterbird Agreement). Retrieved 8 January 2015.

- "These Birds Are Racing to Their Mating Grounds. It's Exhausting". Retrieved 20 July 2018.

- Giraldus Cambrensis "Topographica Hiberniae" (1187), quoted in Edward Heron-Allen, Barnacles in Nature and in Myth, 1928, reprinted in 2003, p. 10. ISBN 0-7661-5755-5 full text at Google Books Archived 5 May 2016 at the Wayback Machine

- Lankester, Edwin Ray (1970) [1915]. Diversions of a Naturalist. p. 119. ISBN 0-8369-1471-6.

this identification was due to the exercise of a little authority on the part of the clergy in both France and Britain, who were thus enabled to claim the abundant "barnacle goose" as a fish in its nature and origin rather than a fowl, and so to use it as food on the fast-days of the Church

- Lankester, Edwin Ray (1970) [1915]. Diversions of a Naturalist. p. 119. ISBN 0-8369-1471-6.

- Raab, Earl (11 October 1974). "The Barnacle Goose and Other Jewish Monsters" (PDF). S. F. Jewish Bulletin.

- "Barnacle Goose". The Medieval Bestiary. Retrieved 10 December 2016.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Branta leucopsis. |

| Wikispecies has information related to Branta leucopsis |

- RSPB Birds by Name: Barnacle Goose

- BirdLife species factsheet for Branta leucopsis

- "Branta leucopsis". Avibase.

- "Barnacle goose media". Internet Bird Collection.

- Barnacle goose photo gallery at VIREO (Drexel University)

- Interactive range map of Branta leucopsis at IUCN Red List maps

- Audio recordings of Barnacle goose on Xeno-canto.