Barbican Estate

The Barbican Estate is an upscale residential complex of around 2,000 flats, maisonettes, and houses within the City of London in Central London, in an area once devastated by World War II bombings and densely populated by financial institutions. Originally built as rental housing for middle and upper-middle class professionals, it remains to this day an upmarket residential estate. It contains, or is adjacent to, the Barbican Arts Centre, the Museum of London, the Guildhall School of Music and Drama, the Barbican public library, the City of London School for Girls and a YMCA (now closed),[1] forming the Barbican Complex.

| Barbican Estate | |

|---|---|

Barbican Towers | |

| |

| General information | |

| Type | Mixed-use development |

| Architectural style | Brutalist/Fortress |

| Town or city | London, EC2 |

| Country | England |

| Design and construction | |

| Architecture firm | Chamberlin, Powell and Bon |

| Structural engineer | Ove Arup & Partners |

| Civil engineer | Ove Arup & Partners |

| Designations | Grade II listed |

| Website | |

| Official website | |

The Barbican Complex is a prominent example of British brutalist architecture and is Grade II listed as a whole,[2] with the exception of the former Milton Court. Milton Court, which once contained a fire station, medical facilities, and some flats, was demolished to allow the construction of a new apartment tower named The Heron, which also contains additional facilities for the Guildhall School of Music and Drama.

History

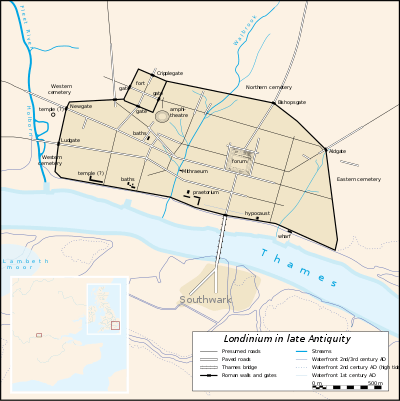

The main fort of Roman London was built between 90 and 120 AD southeast of where the Museum of London now stands at the corner of London Wall and Aldersgate Street.[3] Around 200 AD walls were built around the city that incorporated the old fort, which became a grand entrance known as Cripplegate. The word barbican comes from the Low Latin word Barbecana which referred to a fortified outpost or gateway, such as an outer defence of a city or castle or any tower situated over a gate or bridge which was used for defence purposes.[4] In this case there seems to have been a Roman specula or watchtower[5] in front of the fort at numbers 33–35[5] on the north side of the street then called Barbican[6] (now the west end of Beech St), which was later incorporated into the fortifications north of the wall. The Normans called it the Basse-cour or Base Court,[7] synonymous with the modern word "bailey" and still applied to the outer courtyard of Hampton Court Palace.

The Base Court continued to serve a military function during the reign of Edward I, but Edward III gave it to Robert d'Ufford, 1st Earl of Suffolk[6] who made it his London home. By the 16th century, it had passed to Charles Brandon, 1st Duke of Suffolk. Brandon married his ward Catherine Willoughby, daughter of Maria de Salinas who had been a confidante and lady-in-waiting of Catherine of Aragon and after his death the building was retained by the Willoughby family. The original Base Court seems to have been destroyed and the large building that replaced it was called Willoughby House, a name revived for part of the modern development.

Post-war development

During World War II, the City suffered serious damage and loss of life. The Cripplegate ward was virtually demolished[8] and by 1951 the resident population of the City stood at 5,324 of whom 48 lived in Cripplegate.[9] Discussions began in 1952 about the future of the site, and the decision to build new residential properties was taken by the Court of Common Council on 19 September 1957.[10]

To accommodate the estate, 500 metres of the Metropolitan line was realigned between Barbican and Moorgate stations between 1963 and 1965.[11][12][13]

The estate was built between 1965 and 1976, on a 35-acre (14 ha) site that had been bombed in World War II. The complex was designed by architects Chamberlin, Powell and Bon, whose first work was the ground-breaking Golden Lane Estate immediately north of the Barbican. Unlike its northern neighbour, however, the Barbican Estate was not social housing. Rather, it was designed and built for affluent City professionals and their families, with all flats let out at commercial rents by the Corporation of London.[14] To help let out the flats, brochures were produced, advertising the Barbican Estate as containing the perfect residences for well-heeled professionals and international businesspeople.[15]

Indeed, in its early years, a substantial number of high-profile politicians, lawyers, judges, and bankers made their home here (see famous residents).

The Barbican was never 'council housing' in the conventional sense, as flats were targeted at professionals and let at 'market' rents, i.e. for similar prices to equivalent private homes in Central London. It was, however, owned and managed by the Corporation of the City of London, considered a local authority under the 1980 Housing Act. This meant that Right to Buy applied to it, and, as a result, almost all flats are now privately owned, although a few continue to be let out by the City of London at market (non-subsidised) rents.[16]

The first building on the 40 acres (16 ha) estate, Speed House, was officially opened in 1969, though extensive industrial disputes in the 1970s led to the last building, Shakespeare Tower, only being completed in 1976. It is now home to around 4,000 people living in 2,014 flats.[10] The flats reflect the widespread use in Britain in the 1960s and 1970s of concrete as the visible face of the building. The complex is also characteristic for its total separation of motor vehicles from pedestrians throughout the area. This is achieved through the use of 'highwalks' - walkways of varying width and shape, usually located 1-3 stories above the surrounding ground level. Most pedestrian circulation takes place on these highwalks, while roads and car parking spaces are relegated to the lower level.

The Minister for the Arts, Tessa Blackstone, announced in September 2001 that the Barbican complex was to be Grade II listed. It has been designated a site of special architectural interest for its scale, its cohesion and the ambition of the project.[17] The complex is architecturally important as it is one of London's principal examples of concrete brutalist architecture and considered a landmark.

Various garden features punctuate the brutalist architecture, including a community-run wildlife garden.[18]

Blocks and towers

The residential estate consists of three tower blocks, 13 terrace blocks, two mews and The Postern, Wallside and Milton Court.[19]

The terrace blocks

These are grouped around a lake and green squares. The main buildings rise up to seven floors above a podium level, which links all the facilities in the Barbican, providing a pedestrian route above street level. Some maisonettes are built into the podium structure. There is no vehicular access within the estate, but there are some car parks at its periphery. Public car parks are located within the Barbican Centre.

The terrace blocks are named:[19]

- Andrewes House – named after Lancelot Andrewes a 16th-century English bishop and scholar

- Breton House – named after Nicholas Breton a 16th-century English poet and novelist

- Bryer Court – named after W. Bryer & Sons gold refiners and assayers premises were Numbers 53 and 54 and demolished to make way for the building[20]

- Bunyan Court – named after John Bunyan, a 17th-century English writer and Baptist preacher

- Defoe House – named after Daniel Defoe

- Frobisher Crescent – named after Martin Frobisher, an English seaman and privateer

- Gilbert House – named after Humphrey Gilbert

- Ben Jonson House – named after Ben Jonson, an English playwright, poet and actor

- Thomas More House – named after Thomas More

- Mountjoy House – named after Christopher Mountjoy a French wig-maker who let a room to William Shakespeare[21]

- Seddon House – named after George Seddon, an English cabinetmaker

- Speed House – named after John Speed, an English cartographer and explorer

- John Trundle Court – named after John Trundle

- Willoughby House – named after Catherine Willoughby

Tower blocks

The estate also contains three of London's tallest residential towers, at 42 storeys and 123 metres (404 ft) high. The top two or three floors of each block comprise three penthouse flats. The towers are (east to west):

- Cromwell Tower, completed in 1973 – named after Oliver Cromwell[22]

- Shakespeare Tower, completed in 1976 – named after William Shakespeare[23] and

- Lauderdale Tower, completed in 1974 – named after the Earls of Lauderdale[24]

Once the tallest residential towers in London, they were surpassed by the Pan Peninsula development on the Isle of Dogs.

Barbican complex

The Barbican Estate also contains the Barbican Centre (an arts, drama and business venue), the Barbican public library, the City of London School for Girls, the Museum of London, and the Guildhall School of Music and Drama. A YMCA building was constructed between 1965 and 1971[17] to link the Barbican and Golden Lane Estate; it is also listed. In 2015-16 the YMCA building was converted by Redrow Homes into a new residential block called Blake Tower with 74 flats run as part of the Barbican Estate.

Famous residents

The Barbican has had a number of well-known residents throughout its history, especially in the years immediately after it was completed, when it was considered one of the most prestigious residential developments in London. Famous residents have included:

- Conservative Cabinet Minister Norman Tebbit, who lived in a house on Wallside with his wife until the 1984 Brighton Hotel Bombing [25]

- Leader of the Labour Party John Smith, who lived in Cromwell Tower with his family until his death in 1994 [25]

- Former leader of the National Union of Mineworkers, Arthur Scargill[25]

- Former Prime Minister of Pakistan Benazir Bhutto[25]

- Andrew Bruce, 11th Earl of Elgin

- Writer and broadcaster Clive James [25]

- Film and theatre director Sir Peter Hall [25]

- Footballer George Best [26]

- Investment adviser, commentator and author Bob Beckman [27]

- Political adviser Beryl Goldsmith [28]

- Author, journalist, and broadcaster Brian Redhead [28]

- Senior British judge and Master of the rolls Baron John Donaldson [28] and his wife, the first female Lord Mayor of London Baroness Mary Donaldson [28]

In popular culture

The Barbican features in Michael Paraskos's novel In Search of Sixpence as the home of the lead character, Geroud, and also a bar called "The Gin Bar" loosely based on the Gin Joint bar at the Barbican Centre.[29]

The final scene of the 1983 vampire film, The Hunger directed by Tony Scott and starring David Bowie, Catherine Deneuve and Susan Sarandon, was filmed in the Cromwell Tower at the Barbican.

The Barbican towers can be seen in a sequence from the 1975 Disney film One of Our Dinosaurs is Missing, an unintentional anachronism for a film set in the 1920s.[9]

The Barbican was also used to represent the MI6 headquarters in the James Bond film Quantum of Solace.[30]

Various shots of the Barbican towers are shown on the inner record cover of the 1979 album "Real to Real Cacophony" by the Scottish rock band Simple Minds.

The Barbican is the setting for UK Grime Artist Skepta's 2015 music video for 'Shutdown'.

The estate is the setting of Dua Lipa's music video for her 2016 song Blow Your Mind (Mwah).

The Barbican Estate is mentioned by name in the intro to English band Saint Etienne's song 'Language Lab', from their 2002 Finisterre album.

The titular skyscraper in J.G. Ballard's High Rise (and subsequent film) is largely inspired by the Barbican Estate's towers.[31]

Nearby rail and Tube

| Service | Station/Stop | Line/Route |

|---|---|---|

| National Rail | Liverpool Street | |

| Farringdon | ||

| Moorgate | ||

| London Underground | Liverpool Street | |

| Barbican | ||

| Moorgate | ||

| St Paul's | ||

| Farringdon |

Gallery

- The Barbican Estate features underground parking, making space available for public squares.

A pond features pathways under the water level.

A pond features pathways under the water level. Pond scum has accumulated in a pond.

Pond scum has accumulated in a pond..jpg) A waterfall in the Barbican Gardens.

A waterfall in the Barbican Gardens. Concrete columns in the pond next to Lakeside Terrace

Concrete columns in the pond next to Lakeside Terrace

References and notes

- "Finsbury Hostel Closure". Islington Gazette. Retrieved 2 February 2012.

- Historic England. "Details from listed building database (1352667)". National Heritage List for England. Retrieved 12 June 2011.

- "Quarterly Review (June to August 2002) Greater London Archaeology Advisory Service" (PDF). Quarterly Review. Greater London Archaeology Advisory Service: 30. June–August 2002. Archived from the original (PDF) on 4 January 2009.

- "Barbican Estate history - City of London". cityoflondon.gov.uk.

- Britton, John (1815). The Beauties of England and Wales, or, Delineations, topographical, historical, and descriptive, of each county, Volume 10, Part 3. Vernor and Hood. p. 216.

- Strype, John (1720). "6". Survey of London. 3. Retrieved 19 March 2014.

- Goff, Cecilie (1930). A woman of the Tudor age. John Murray. p. 277.

- Watts, Peter (2 September 2015). "Blitzed, rebuilt and built again: what became of London's bomb sites?". the Guardian.

- "5 Secrets Of Barbican". londonist.com. 17 February 2017.

- "History of the Barbican Estate". City of London. Archived from the original on 7 December 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- London Transport Track Realignment on City Site Railway Gazette 30 June 1963 page 229

- Barbican Rerouting The Railway Magazine issue 750 October 1963 pages 685, 732

- Final track changeover at Barbican The Railway Magazine issue 777 January 1966 pages 49/50

- "Never social housing". nicolalee.co.uk. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Never social housing". barbicanliving.co.uk. Retrieved 22 April 2020.

- "Who are we?". barbicanliving.co.uk. Retrieved 18 September 2019.

- "Listing of the Barbican complex". City of London. Archived from the original on 8 October 2006. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- Weston, Phoebe (28 April 2020). "'Nature survives in the tiniest corners': the City of London's wild heart". The Guardian. Archived from the original on 28 April 2020.

- Jennifer Clarke (1990), The Barbican Sitting on History, Corporation of London Records Office, ISBN 9780852030301, OCLC 24713108, OL 8280417M, 0852030304

- "Barbican frieze". London Remembers.

- "The Mountjoys". barbicanliving.co.uk. 23 October 2015.

- "Cromwell Tower". Emporis Buildings. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- "Shakespeare Tower". Emporis Buildings. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- "Lauderdale Tower". Emporis Buildings. Retrieved 11 January 2007.

- "Meet the Barbican's original residents". Retrieved 24 April 2020.

- Robert Humphreys, The Rough Guide to London (London: Rough Guides, 2003) ISBN 9781843530930

- "The sound of money", Pearson Phillips, The Times, 29 April 1987, p. 14.

- "Barbican comes of age", Jon Stock, The Times, 23 February 1991, p. 17.

- Michael Paraskos, In Search of Sixpence (London: Friction Fiction, 2015) ISBN 9780992924782

- Needham, Alex (29 February 2012). "Barbican to stage an exhibition to mark 50 years of James Bond films". the Guardian.

- Lloyd, Joe (16 March 2016). "High-Rise: the brutal truth". 1843 Magazine.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Barbican Estate. |