Bahira

Bahira (Arabic: بَحِيرَىٰ, Classical Syriac: ܒܚܝܪܐ) was an Arab[1] Nestorian or possibly Gnostic Nasorean[2] monk who, according to Islamic tradition, foretold to the adolescent Muhammad his future as a prophet.[3][4] His name derives from the Syriac bḥīrā, meaning “tested (by God) and approved”.[5]

Saint Bahira | |

|---|---|

Text illustration of the name Bahira in Aramaic | |

| Tested (by God) and approved | |

| Hometown | Bosra, Syria |

| Major shrine | Monastery of Saint Bahira, Bosra, Syria |

| Part of a series on |

| Muhammad |

|---|

|

|

Views |

|

Related |

|

Islamic tradition

The story of Muhammad's encounter with Bahira occurs in the works of the early Muslim historians Ibn Hisham (died 833 CE), Ibn Sa'd al-Baghdadi (784-855), and Muhammad ibn Jarir al-Tabari (839-923), whose versions differ in some details. The young Muhammad, then either nine or twelve years old, met Bahira in the town of Bosra in Syria while travelling with a Meccan caravan, accompanying his uncle Abu Talib ibn ‘Abd al-Muttalib.[3] When the caravan passed by his cell, the monk invited the merchants to a feast. They accepted the invitation, leaving the boy to guard the camel. Bahira, however, insisted that everyone in the caravan should come to him.[4] Then a miraculous occurrence indicated to the monk that Muhammad would become a prophet.

The movement of a cloud that kept shadowing Muhammad regardless of the time of the day drew Bahira's attention. The monk revealed his visions of Muhammad's future to the boy's uncle (Abu Talib), warning him to preserve the child from the Jews (in Ibn Sa'd's version) or from the Byzantines (in al-Tabari's version). Both Ibn Sa'd and al-Tabari write that Bahira found the announcement of the coming of Muhammad in the original, unadulterated gospels, which he possessed.[3]

A similar tradition is attributed to Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri in the works of the early ahadith compiler ‘Abd al-Razzaq al-San‘ani, in which the unnamed figure is a rabbi of Tayma instead of a Christian Syrian monk.[6] The rabbi warns Abu Talib against bringing Muhammad to Syria, as he predicts that Muhammad will be killed by the Syrian Jews if they proceed. Abu Talib returns back to Mecca with his nephew. Later Islamic writers gave the rabbi the name of Bahira.[7]

Christian tradition

In the Christian tradition Bahira became a heretical monk, whose errant views inspired the Qur'an. Bahira is at the center of the Apocalypse of Bahira, which exists in Syriac and Arabic which makes the case for an origin of the Qur'an from Christian apocrypha. Certain Arabist authors maintain that Bahira's works formed the basis of those parts of the Qur'an that conform to the principles of Christianity, while the rest was introduced either by subsequent compilers such as Uthman Ibn Affan or contemporary Jews and Arabs.

The names and religious affiliations of the monk vary in different Christian sources. For example, John of Damascus (d.749), a Christian writer, states that Muhammad "having chanced upon the Old and New Testaments and likewise, it seems, having conversed with an Arian monk, devised his own heresy."[8]

For Abd-al-Masih al-Kindi, who calls him Sergius and writes that he later called himself Nestorius, Bahira was a Nasorean, a group usually conflated with the Nestorians. After the 9th century, Byzantine polemicists refer to him as Baeira or Pakhyras, both being derivatives of the name Bahira, and describe him as an iconoclast. Sometimes Bahira is called a Syrian Jacobite or an Arian. The early Christian polemical biographies of Muhammad share in claiming that any supposed illiteracy of Muhammad did not imply that he received religious instruction solely from the angel Gabriel, and often identified Bahira as a secret, religious teacher to Muhammad.[5]

Gallery

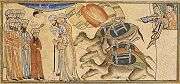

A young Mohammed being recognized by the monk Bahira. Miniature illustration on vellum from the book Jami' al-Tawarikh (literally "Compendium of Chronicles" but often referred to as The Universal History or History of the World), by Rashid al-Din Hamadani, published in Tabriz, Persia, 1307 A.D. Now in the collection of the Edinburgh University Library, Scotland

A young Mohammed being recognized by the monk Bahira. Miniature illustration on vellum from the book Jami' al-Tawarikh (literally "Compendium of Chronicles" but often referred to as The Universal History or History of the World), by Rashid al-Din Hamadani, published in Tabriz, Persia, 1307 A.D. Now in the collection of the Edinburgh University Library, Scotland The Monastery of Bahira the Monk in Bosra, Syria Partially remaining

The Monastery of Bahira the Monk in Bosra, Syria Partially remaining- Monastery of Bahira the Monk Bosra, Syria

Muhammad and the Monk Sergius, engraving of 1508 by Lucas van Leyden (The soldier takes Muhammad's sword. see text)

Muhammad and the Monk Sergius, engraving of 1508 by Lucas van Leyden (The soldier takes Muhammad's sword. see text)

Bibliography

- Maulana Muhammad Ali (2002), The Holy Qur'an: Arabic Text with English Translation and Commentary, New Addition, Ahmadiyya Anjuman Isha’ at Islam Lahore Inc., Ohio, USA.

- Osman Kartal (2009), The Prophet’s Scribe Athena Press, London (a novel)

- B. Roggema, The Legend of Sergius Baḥīrā. Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam (The History of Christian-Muslim Relations. Texts and Studies 9; 2008) (includes editions, translations and further references).

- K. Szilágyi, Muhammad and the Monk: The Making of the Christian Baḥīrā Legend, Jerusalem Studies in Arabic and Islam 34 (2008), in press.

- Abel, A. (1935) “L'Apocalypse de Bahira et la notion islamique du Mahdi” Annuaire de l'Institut de Philologie et d'Histoire Orientale III, 1-12. Alija Ramos, M.

- Griffith, S. H. (1995). "The legend of the Monk Bahira; the Cult of the Cross and lconoclasm". In P. Canivet; J-P. Rey (eds.). Muhammad and the Monk Bahîrâ: Reflections on a Syriac and Arabic text from early Abbasid times. 79. Oriens Christianus. pp. 146–174. ISSN 0340-6407. OCLC 1642167.

- Griffith, S. H. (January 2000). "Disputing with Islam in Syriac: The Case of the Monk of Bêt Hãlê and a Muslim Emir". Hugoye: Journal of Syriac Studies. 3 (1). Archived from the original on 2006-07-16.

References

- Al-Masudi, "Muruj adh-Dhahab wa Ma'adin al-Jawhar" ,وقال المسعودي، ت : 345 هـ إن بحيرا الراهب على دين المسيح عيسى بن مريم، واسم بحيرا في النصارى سرجس، وكان من عبد القيس.

- John of Damascus, Des hérésies, chap. CI.

- Abel, A. "Baḥīrā". Encyclopaedia of Islam, Second edition. Brill. Brill Online, 2007 [1986].

- Watt, W. Montgomery (1964). Muhammad: Prophet and Statesman, p. 1-2. Oxford University Press.

- Roggema, Barbara. "Baḥīrā." Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE. Edited by: Gudrun Krämer, Denis Matringe, John Nawas, Everett Rowson. Brill Online, 2014 [2011]. Accessed July 12, 2014.

- ibn Rashid, Mamar. The Expeditions: An Early Biography of Muhammad. Translated by Sean W. Anthony. NYU Press. p. 9. ISBN 978-0814769638.

- Roggema, Barbara (2009). The Legend of Sergius Baḥīrā: Eastern Christian Apologetics and Apocalyptic in Response to Islam. Brill. p. 44. ISBN 978-9004167308.

- St. John of Damascus's Critique of Islam; from Writings, by St John of Damascus (De Haeresibus, chap. 101), The Fathers of the Church vol. 37 (Washington, DC: Catholic University of America Press, 1958), pp. 153-160.