Atari 2600 homebrew

Atari 2600 homebrew is a video game genre, where "homebrew" is synonymous with "hobbyist-developed," for the Atari 2600 video game console. The first 2600 homebrew game was written in 1995, and since then more than 100 games have been released. There is an active community of Atari 2600 developers—the largest among classic video game homebrew communities.[1]

The majority of homebrew games are unlicensed clones of arcade games, personal computer games, and games from other consoles, but there are also ROM hacks and some original games. Several games have received attention outside the homebrew community; some have been included in an Atari 2600 game anthology by Activision.[2]

With severe resource limitations such as only 128 bytes of RAM and no video frame buffer, the 2600 is a difficult machine to program.[3] Tools such as emulators, the Batari Basic language, and freely available documentation, can help the hobbyist developer.[3]

History

The Atari 2600 game console was introduced to the market by Atari, Inc. in 1977 as the Atari Video Computer System or Atari VCS for short.[4] Since the console's release, hundreds of different games by dozens of game manufacturers have been released for the console,[5] with millions of copies sold of each of the most popular games, such as Pac-Man, Pitfall! and Missile Command.[6] Atari 2600 consoles continued to be manufactured throughout the 1980s, but Atari Corporation dropped support in January 1992.[7]

The next year, hobbyist Harry Dodgson released the first homebrew cartridge, titled 7800/2600 Monitor Cartridge.[8] The cartridge was not a game, but rather a diagnostic tool that Dodgson hoped to persuade Atari Corp to market to customers interested in programming their own Atari 7800 games. As Atari no longer manufactured the keyboard controller required by the cartridge, they declined, so Dodgson decided to manufacture and market the cartridge on his own.[8]

Dodgson purchased a batch of Atari 7800 Hat Trick games at Big Lots for a dollar or less each, and cannibalized the parts to create the new monitor cartridge. He then advertised the cartridge on Usenet and in a catalog for video game store Video 61, ultimately selling around 25 cartridges. With the relatively small number of hand-made cartridges, the game is considered a rarity among homebrews.[8] The rights to the cartridge were later purchased by Video 61.[8]

In 1995 – three years after Atari's withdrawal of the 2600 from the marketplace – independent developer Ed Federmeyer released another Atari 2600 homebrew project, titled SoundX,[9] a cartridge that demonstrated the sound capabilities of the Atari 2600.[10] Federmeyer used the term "homebrew" to describe this type of hobbyist-driven development, inspired by the California Homebrew Computer Club of early computer enthusiasts that included Apple founders Steve Jobs and Steve Wozniak.[11] Originally designing the cartridge for his own use, Federmeyer decided to gauge interest among fellow retro game enthusiasts; like Dodgson, Federmeyer advertised his creation on Usenet, ultimately receiving over 50 responses.[12] Following SoundX, Federmeyer created an unlicensed port of the game Tetris, titled Edtris 2600.[10]

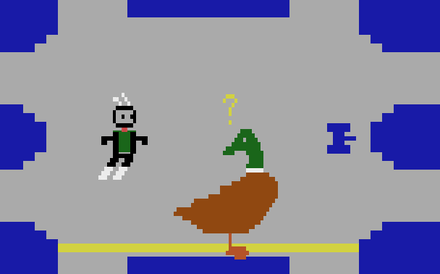

Since then, over 100 homebrew games for the Atari 2600 have been released,[13] many by AtariAge, a website that features "information on game cartridges, consoles, Atari artwork and all other topics Atari".[14] Among them are the boxing game K.O. Cruiser by Devin Cook, Halo 2600 by Ed Fries, and Duck Attack! by Will Nicholes – all released at the Classic Gaming Expo in July 2010.[15] In 2012, homebrewers Thomas Jentzsch and Andrew Davie released an officially licensed 2600 port of Boulder Dash – a game they had been working on for nearly 10 years. There currently exists an active community of Atari 2600 homebrew developers.[7][16]

Types of projects

.png)

Most hobbyist-developed Atari 2600 games were created for the technical challenge, not as exercises in game design, and are unlicensed clones of arcade and computer games that were popular during the 1980s. Lady Bug, released by John W. Champeau in 2006, is an implementation of the 1981 Universal arcade game.[17] Juno First, released by Chris Walton in 2009, borrows the name and design of the 1983 Konami arcade game;[18] and Thrust, released by Thomas Jentzsch in 2000, is a clone of the 1986 computer game of the same name, originally designed for the BBC Micro.[19] Other programmers have implemented Sea Wolf (as Seawolf), Tetris (as Edtris 2600), and Caverns of Mars (as Conquest of Mars). The 2600 version of Star Castle was undertaken because it had previously been said that "a decent version couldn’t be done."[20]

Several homebrew games have expanded upon earlier games. Warring Worms by Billy Eno (2002), takes the core design of Surround and adds new gameplay modes, such as the ability to fire shots at the opponent.[21] Medieval Mayhem by Darrell Spice Jr., is a re-imagining of the game Warlords with enhanced graphics and additional gameplay options.[22]

While the majority of the hobbyist development community uses designs from existing games, there are also original titles. In SCSIcide, released by Joe Grand in 2001,[1] the player acts as a hard drive read head picking up color-coded data bits as they fly past.[23] Oystron, released by Piero Cavina in 1997, is an action game in which "space oysters" are opened and pearls collected to earn ammunition. Duck Attack! allows the player to battle giant, fire-breathing ducks in a quest to save the world from a mad scientist.[24]

A demake is a port from a system generations past the 2600.[25] Halo 2600 is a 4 KB game inspired by the Halo series of games.[26] It was written by former Microsoft vice-president Ed Fries, who was involved in Microsoft's acquisition of Halo creator Bungie.[27] Other 2600 demakes include the Portal-inspired Super 3D Portals 6 and a demo based on the Mega Man franchise.[28]

ROM hacking modifies existing ROM images. Modifications typically include new graphics and game colors, but may also include gameplay modifications and the ability to use a different controller than the one for which the game was originally designed.[29] One hack target is the 2600 version of Pac-Man, in which the graphic elements are reworked to more closely resemble the arcade version.[30]

Games

_1.png)

In 2003, Activision selected several homebrew 2600 games for inclusion in the Game Boy Advance version of its Activision Anthology: Climber 5 by Dennis Debro (2004), Okie Dokie by Bob Colbert (1996), Skeleton+ by Eric Ball (2003), Space Treat Deluxe by Fabrizio Zavagli (2003), Vault Assault by Brian Prescott (2001), Video Euchre by Erik Eid (2002), and Oystron.[31] In 2005, SCSIcide, Oystron, Warring Worms, Skeleton+, and Marble Craze by Paul Slocum (2002) were listed as the "Best 2600 Homebrew Games" in the book Gaming Hacks: 100 Industrial-Strength Tips & Tools by Simon Carless.[23]

Homebrews that have received attention outside the homebrew community include Halo 2600,[32][33] Duck Attack!,[34] and A-VCS-tec Challenge by Simon Quernhorst (2006), an unofficial port of the 1981 Atari 8-bit family game Aztec Challenge.[35]

In May 2018 it was announced that the Retron 77, a clone of the Atari 2600 console, would include four homebrew pack in-games: Astronomer,[36] Baby,[37] Muncher 77,[38] and Nexion 3D.[39]

Development

The Atari 2600 is generally considered to be a very demanding programming environment, with a mere 128 bytes of RAM available without additional hardware, and no video frame buffer at all. The programmer must prepare each line of video output one at a time as it is being sent to the television. The only sprite capabilities the 2600 offers are one-dimensional 1-bit and 8-bit patterns; creating a two-dimensional object requires changing the pattern between each line of video.[3] Atari 2600 emulators such as Stella and Z26 are often used by homebrewers to test their games as they are being developed.[1] Unlike later consoles, the Atari 2600 does not require a modchip to run homebrew cartridges; it will run any properly written program without checking for a digital signature or performing any other type of authentication.[40] It was this aspect of the hardware design that enabled third-party companies such as Activision and Imagic to develop Atari 2600 games without Atari's consent in the 1980s.[3] This led Atari to incorporate authentication features in its later console, the Atari 7800, to prevent other companies from creating and selling their own 7800 games without Atari's permission.[40]

With third-party hardware such as the Cuttle Cart and Harmony Cartridge, developers could load in-progress games onto a physical Atari console to test.[41][42] The Cuttle Cart, developed by Chad Schell in the early 2000s,[43] was designed to be compatible with the Starpath Supercharger, and allowed ROM images to be loaded via an 1/8" minijack audio interface such as a cassette tape or CD player.[44]

Batari Basic

As the 2600 uses the 6507, a variant of the MOS Technology 6502 chip, as its CPU, most homebrews released are written in 6502 assembly language. However, in 2007, developer Fred X. Quimby ("batari" on Atari fandom forums) released a compiler, Batari Basic which allows developers to create 2600 games in BASIC, a high-level programming language.[3] Game designer and Georgia Institute of Technology associate professor Ian Bogost has used Batari Basic in his classes to teach students video game concepts and history.[3] An integrated development environment (IDE), Visual Batari Basic, is also available. Written by Jeff Wierer and released in 2008, it runs on Microsoft Windows and requires .NET Framework 3.0.[45][46]

See also

References

- Wen, Howard (May 20, 2004). "Inside the Homebrew Atari 2600 Scene". Archived from the original on 4 November 2010. Retrieved September 28, 2010.

- Carless 2005, p. 22.

- Bogost & Montfort 2009.

- "Atari VCS (Atari 2600)". A Brief History of Game Console Warfare. Business Week. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Atari 2600 Companies". AtariAge. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Buchanan, Levi (August 26, 2008). "Top 10 Best-Selling Atari 2600 Games". IGN. Retrieved September 29, 2010.

- Gray, Frank (July 25, 2010). "Ducks roam new game for old Atari". The Journal Gazette. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Herman, Leonard. "New Blood for Orphaned Systems". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. p. 2. Archived from the original on August 18, 2000. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Rarity Key Explained". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Herman 1997, p. 251.

- Herman, Leonard. "New Blood for Orphaned Systems". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. p. 1. Archived from the original on August 15, 2000. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Herman, Leonard. "New Blood for Orphaned Systems". GameSpot. CBS Interactive. p. 3. Archived from the original on August 18, 2000. Retrieved January 17, 2016.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Atari 2600 Rarity Guide". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Caylor, Bob (August 18, 2010). "Atari revival". The News-Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- "Classic Gaming Expo: AtariAge Announces New Games for CGE". Archived from the original on 27 August 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Carless 2005, p. 15: "As discussed earlier, the Atari 2600 itself has a vibrant homebrew scene oriented around such sites as Atari Age."

- Yarusso, Albert. "Lady Bug". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Walton, Chris (May 6, 2008). "Juno First - Final Version (Atari 2600)". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Thrust+ DC Edition". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- "Star Castle 2600, the Story". Star Castle 2600.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Warring Worms". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Medieval Mayhem". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Carless 2005, p. 21.

- McGinnis, Jeff (August 4, 2010). "Tech-savvy fans programming, developing on classic console". Toledo Free Press. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- Snow, Jean (September 12, 2008). "Portal, Retrofitted for Atari 2600". Wired. Retrieved August 28, 2010.

- Bogost, Ian (August 1, 2010). "Halo 2600: Ed Fries demakes Halo for Atari". Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Bishop, Todd (January 14, 2004). "The game is over for Xbox's Ed Fries". Seattle Post-Intelligencer. Retrieved September 2, 2010.

- Winterhalter, Ryan (April 29, 2011). "31 Homebrew Games Worth Playing". 1UP.com. Retrieved May 10, 2011.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Atari 2600 Hacks". AtariAge. Archived from the original on 29 August 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Yarusso, Albert. "Atari 2600 Hacks: Pac-Man". AtariAge. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Kohler 2005, p. 378.

- Melanson, Donald (August 3, 2010). "Former Microsoft VP brings Halo to the Atari 2600". Engadget. Archived from the original on 4 August 2010. Retrieved August 5, 2010.

- Beschizza, Rob (August 3, 2010). "Former Microsoft VP brings Halo to the Atari 2600". Boing Boing. Archived from the original on 6 August 2010. Retrieved August 27, 2010.

- Duck Attack! references:

- McGinnis, Jeff (August 4, 2010). "Tech-savvy fans programming, developing on classic console". Toledo Free Press. Archived from the original on January 4, 2013. Retrieved August 4, 2010.

- Gray, Frank (July 25, 2010). "Ducks roam new game for old Atari". The Journal Gazette. Archived from the original on 30 August 2010. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- Caylor, Bob (August 18, 2010). "Atari revival". The News-Sentinel. Archived from the original on May 11, 2011. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- "Interview: Will Nicholes". Kittysneezes.com. August 23, 2010. Retrieved August 24, 2010.

- Doctorow, Cory (July 10, 2006). "New Atari 2600 game cartridge released". Boing Boing. Retrieved August 26, 2010.

- "Astronomer 2600 Official website". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Baby 2600 Official website". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Muncher store website". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "Nexion 3D on AtariAge". Retrieved 22 June 2018.

- "The Atari 7800 ProSystem". AtariMuseum.com. Archived from the original on 2013-01-17. Retrieved 2010-08-28.

- George, Gregory D. (April 12, 2005). "Cuttle Cart 2". The Atari Times. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Borys, Michael (November 18, 2015). "The Harmony Cartridge". Boing Boing. Retrieved November 22, 2018.

- Grand, Joe. Game Console Hacking: Having Fun While Voiding Your Warranty. pg. 393. ISBN 978-1-931836-31-9.

- Carless, Simon. Gaming Hacks. pg. 16. ISBN 978-0-596-00714-0.

- Wierer, Jeff (April 5, 2008). "Visual bB 1.0 - a new IDE for batari Basic". Archived from the original on 18 August 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- "Visual batari Basic Guide". Archived from the original on 27 July 2010. Retrieved August 30, 2010.

- Bogost, Ian; Montfort, Nick (2009). Racing the Beam: The Atari Video Computer System. MIT Press. ISBN 0-262-01257-X.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Carless, Simon (2005). Gaming Hacks: 100 Industrial-Strength Tips & Tools. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 0-596-00917-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Herman, Leonard (1997). Phoenix: The Fall & Rise of Videogames. Rolenta Press. ISBN 0-9643848-2-5.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

- Kohler, Chris (2005). Retro Gaming Hacks: Tips & Tools for Playing the Classics. O'Reilly Media. ISBN 0-596-00917-8.CS1 maint: ref=harv (link)

External links

- AtariAge: Atari 2600 programming

- Batari Basic, a BASIC compiler for the Atari 2600