African-American women in politics

African-American women have been involved in American socio-political issues and advocating for the community since the American Civil War era through organizations, clubs, community-based social services, and advocacy. African-American women are currently underrepresented in the United States in both elected offices and in policy made by elected officials.[1] Although data shows that women do not run for office in large numbers compared to men,[1] African-American women have been involved in issues concerning identity, human rights, child welfare, and misogynoir within the political dialogue.

History

Suffrage and voting rights

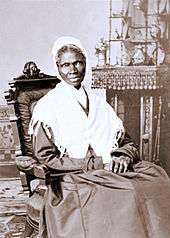

Efforts to attain universal suffrage began during the 1860s in response to the events of the American Civil War. It was Sojourner Truth who gave a historic speech during the Women's Convention in Akron, Ohio, on May 29, 1851, that made many people stop and listen and was introduced to a wider audience when transcribed and published by Marius Robinson, an abolitionist reporter. The speech, "Ain't I A Woman?" discussed American white women's privilege, and the courtesies that were not given to African-American women. While African-American men attained the vote in 1870 with the passage of the 15th Amendment, African-American women were still unable to participate in political elections. It was during the 1890s that women's suffrage efforts began. During the period, African-American women were widely minimized or ignored due to racism from white suffragists or general sexism.[2]

Though women obtained the right to vote in the United States in 1920, many women of color still ran into obstacles. Some faced tests that required them to interpret the Constitution in order to vote.[2] Others were threatened with physical violence, false charges, and other extreme danger to prevent voting.[3] Due to these tactics and others that marginalized people of color, the Voting Rights Act of 1965 was put into place. It outlawed any discriminatory acts to prevent people from voting.

Women and the Black Power Movement

Despite some of the elements of the Black Power movement that had views centered on misogyny,[4] African-American women quickly found a voice in the movement. Women held leadership positions, ran community-based programs, and fought misogyny.[4] Other women also contributed to the grass-roots movement through community service.[5]"In the age of rights, antipoverty, and power campaigns, black women in community-based and often women-centered organizations, like their female counterparts in nationally known organizations, harnessed and engendered Black Power through their speech and iconography as participants of tenant councils, welfare rights groups, and a black female religious order."[6]

Political representation

African-American women have been underrepresented in politics within the United States, but numbers continue to increase. According to the Center for American Women and Politics at Rutgers University, currently 13 African-American women serve in the 112th Congress, with 239 state legislators serving nationwide.[7] The paths to public office for women in the African-American community have differed from men and other groups, such as women's organizations,[8] rallies, and fundraisers.

United States House of Representatives

Overall, 19 states, including the U.S. Virgin Islands and the District of Columbia, have elected an African-American woman to represent them in the U.S. House. There are currently 42 African-American female representatives and three African-American female delegates in the United States House of Representatives. Most are members of the Congressional Black Caucus. The first African-American woman to serve as a representative was Shirley Chisholm from New York's 12th congressional district in 1969 during the Civil Rights Movement.

United States Senate

African-American women in the United States Senate are underrepresented twofold: the United States Senate has had ten African-American elected or appointed office holders and only two female African-American senators.[9] Despite this, African-American women are increasingly running and being elected or appointed to offices.

In 1993, Carol Moseley Braun became the first African American woman to be elected to the United States Senate, and the only female senator from Illinois. Braun's shock at Democratic incumbent senator Alan Dixon's vote to confirm Clarence Thomas after his 1991 sexual harassment scandal motivated her successful primary campaign against Dixon. Shortly after being elected, Braun took a one-woman stand against the United Daughters of the Confederacy's renewal of patent for the Confederate flag as their insignia.[10] Though Braun considered it a non-issue, she was still puzzled: "Who would have expected a design patent for the Confederate flag?"[11] Incredibly, Braun was able to sway the Senate vote against renewal of the patent. The United Daughters of the Confederacy no longer uses the confederate flag as their insignia.

Kamala Harris began serving as the junior United States Senator from California in 2017. In 2004, she was elected the 27th District Attorney of San Francisco and served from 2004 to 2011. During that time, Harris created a unit to tackle environmental crimes[12] and a Hate Crimes Unit that focused on hate crimes committed against LGBT youth in schools.[13] In 2010, Harris won the election as California's Attorney General by less than 1 point and about 50,000 votes. She was then re-elected in 2014 by a wide margin.

Harris has a strong record of bipartisan cooperation with her Republican colleagues, having introduced a multitude of bills with Republican co-sponsors, including a bail reform bill with Senator Rand Paul,[14] an election security bill with Senator James Lankford,[15] and a workplace harassment bill with Senator Lisa Murkowski.[16] Senate Judiciary Chairman Lindsey Graham said of Harris: "She's hard-nosed. She's smart. She's tough."[17]

Cabinet, Executive Departments, and Agencies

The United States Cabinet has had five African-American female officers. Patricia Roberts Harris was the first African-American woman to serve in the Cabinet; she was appointed Secretary of Housing and Urban Development in 1977 by President Jimmy Carter. Hazel R. O'Leary became the second African-American woman to serve in the Cabinet during the Clinton administration as Secretary of Energy. Alexis Herman was the first African-American woman to serve as the Secretary of Labor during the tenure of President Bill Clinton as well.

Condoleezza Rice was appointed Secretary of State in 2005 under the Bush administration, and thus became the first African-American woman to serve as Secretary of State as well as the highest-ranking woman in the United States presidential line of succession in history.[18] Rice also became the first woman to serve as the National Security Advisor.

Loretta Lynch served as the 83rd attorney general of the United States from 2015 to 2017 during the Obama Administration. Lynch succeeded Eric Holder and had previously served as the United States Attorney for the Eastern District of New York under both Presidents Bill Clinton and Barack Obama. On November 8, 2014, President Barack Obama nominated Lynch for the position of U.S. Attorney General, to succeed Eric Holder. Her nomination process was one of the longest in the history of the United States, taking 166 days after she was first nominated for the post.[19] She was confirmed by the Senate Judiciary Committee on February 26, 2015, and approved by the Senate in a 56-43 vote,[20] thereby becoming the first African-American woman to hold this office.[21][22] She was sworn in by Vice President Joe Biden on April 27, 2015.[23]

Presidential Campaigns

Though African-American women have run for presidential nomination in several campaigns, many have been labeled as "non-viable" due partly to their party affiliations, i.e., Charlene Mitchell in 1968 for the Communist Party USA, Lenora Fulani in 1988 for the New Alliance Party, and Cynthia McKinney in 2008 for the Green Party. Shirley Chisholm ran as both the "black candidate" and the "woman candidate" in the 1972 presidential campaign and "found herself shunned by leaders from the political establishments she helped to found—the Congressional Black Caucus and the National Women's Political Caucus."[24] Still, Chisholm was able to gain 151 votes at the Democratic National Convention, despite missing the presidential nomination.[24]

Although the office of the First Lady of the United States is not a political office, Michelle Obama, the first African-American First Lady, has made an impact on women in the 21st century. Obama became first Lady of the United States in 2009, when her husband, Barack Obama, took office as President of the United States. Michelle Obama has donated her services to soup kitchens, homeless shelters, and other urban social services,[25] but she eventually found her niche in childhood obesity. Ms. Obama has created Let's Move![26] in an effort to reduce childhood obesity around the nation.[27]

On January 21, 2019, Kamala Harris, junior United States Senator from California, officially announced her candidacy for President of the United States in the 2020 United States presidential election.[28] Over an estimated 20,000 people attended her formal campaign launch event in her hometown of Oakland, California.[29]

While Harris initially had high numbers over several of her opponents,[30] she fell in the polls following the second presidential debate.[31] On December 3, 2019, Harris withdrew from seeking the 2020 Democratic nomination, despite having been initially considered a potential frontrunner for the 2020 Democratic nomination for President.[32][33]

Misogynoir in Politics

Misogynoir is misogyny directed towards black women where race and gender both play roles in bias. It was coined by queer Black feminist Moya Bailey. The term was created to tackle the misogyny directed toward black women in American visual and popular culture as well as in politics. In the U.S political sphere, misogynoir has led to the lack of African American Women in politics. The number of African-American elected officials has increased since 1965, however black people remain underrepresented at all levels of government. Black Women make up less than 3% of U.S. representatives and there were no black women in the U.S. Senate as late as 2007.[34]

In comparison to Black Man, Black Women tend to be more active participants in the electoral process and this could lead to more potential for Black Women to equal or surpass Black Men in the number of elected officials within their race.[35] However, because of issues of both race and gender it has been much harder for African-American Women to rise in the political sphere. When fighting for equal voting rights, Black Women found that they were often surrounded by sexist Black Men who did not want them to rise in power, and racist White Women who did not want them to be on the same level.[36]

Organizations

A number of organizations supporting African-American women have historically played an important role in politics.[37] The National Association of Colored Women (NACW), founded in 1896 by Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin and Mary Church Terrell, is one of the oldest political groups created for and by African-American women. Among its objectives were equal rights,[38] eliminating lynching, and defeating Jim Crow laws. Another organization, the National Council of Negro Women (NCNW), was founded in 1935 by civil rights activist Mary McLeod Bethune and was more involved in African-American politics with the aim to improve the quality of life for African-American women and families. NCNW still exists today as a non-profit organization reaching out through research, advocacy, and social services in the United States and Africa.

In 1946 Mary Fair Burks founded the Women's Political Council (WPC) as a response to discrimination in the Montgomery League of Women Voters, who refused to allow African-American women to join.[39] The WPC sought to improve social services for the African-American community and is famously known for instigating the Montgomery Bus Boycott.[40]

In the 1970s, the National Black Feminist Organization (NBFO) sought to address issues unique to African-American women such as racism, sexism, and classism. Though in previous years feminism and suffrage had been considered a white women's fight, NBFO "refused to make black women choose between being black and being female."[41] Margaret Sloan-Hunter, one of its founders, went on to help found Ms. Magazine, a magazine focusing on a feminist take on news issues. Though the organization had disintegrated by 1977, another organization, which formed just a year after the NBFO in 1974, turned out to be one of the most important black feminist organizations of our time. Combahee River Collective was founded by African-American feminist and lesbian, Barbara Smith, and described themselves as a "collective of Black feminists [...] involved in the process of defining and clarifying our politics, while [...] doing political work within our own group and in coalition with other progressive organizations and movements."[42] Perhaps the most notable piece to come out of the Combahee River Collective was the Combahee River Collective Statement, which helped to expand on ideas about identity politics.[43]

In 2014, political activist and women's rights leader Leslie Wimes founded the Democratic African-American Women's Caucus in Florida. She enlisted the help of Wendy Sejour and Mayor Daisy black to help African-American Women in the state of Florida have a voice.[44] In the last two presidential elections, the turnout percentage of African-American women was greater than all other demographic groups, yet has not translated into more African-American Women in office, or political power for African-American women. Virginia Governor Terry McAuliffe credits African-American Women for his win in the state.[45] Black women-owned businesses are the fastest growing segment of the women owned business market.[46] The DAAWC seeks to increase the number of elected African-American Women on the State and Federal levels, as well as focus on issues specific to African-American Women. While the DAAWC begins in the state of Florida, the organization is hoping to expand to other states to mobilize the political power of African-American Women.

Assata's Daughters was founded in March 2015 by Page May in order to protest against the lack of response to Eric Garner's death.[47][48] Centered in Chicago, Assata's Daughters is named after controversial Black Panther Party and Black Liberation Army member Assata Shakur.[49][50][51] The organization is part of a cluster of black activist organizations known as the Movement for Black Lives.[47] Assata's Daughters has worked to speak out against police militarization, immigrant deportation, the Dakota Access Pipeline, and President Donald Trump.

Socio-Political Movements

20th Century

Civil Rights

The civil rights movement in the United States was a decades-long struggle by African Americans to end legalized racial discrimination, disenfranchisement and racial segregation in the United States. The social movement's major nonviolent resistance campaigns eventually secured new protections in federal law for the human rights of all Americans. During this time women had very few opportunities for leadership positions within the movement, leaving them to tend to informal leadership or supportive roles in the background.[52] Still, some women made an impact in the movement, such as Coretta Scott King, Dorothy Height, and Septima Clark.

Coretta Scott King, wife of Martin Luther King Jr., was an active advocate for African-American equality, she was a leader for the Civil rights movement in the 1960s. King played a prominent role in the years after her husband's assassination in 1968 when she took on the leadership of the struggle for racial equality herself and became active in the Women's Movement. Coretta Scott King founded the King Center and sought to make her husband's birthday a national holiday. She later broadened her scope to include both advocacy for LGBT rights and opposition to apartheid. She was inducted into the Alabama Women's Hall of Fame, the National Women's Hall of Fame, and was the first African American to lie in the Georgia State Capitol.[53] King has been referred to as "First Lady of the Civil Rights Movement".[54]

Dorothy Height is credited as the first leader during the civil rights movement to recognize inequality for both women and African Americans concurrently and was the president of the National Council of Negro Women for forty years.[55][56] Height started working as a caseworker with the New York City Welfare Department, and at the age of 25, she began a career as a civil rights activist and joined the National Council of Negro Women. During the Civil Rights Movement, Height organized "Wednesdays in Mississippi,"[57] which brought together black and white women from the North and South to create a dialogue of understanding. She fought for equal rights for both African Americans and women. Height was one of the only known women to partake in the organization of the March on Washington for Jobs and Freedom.[55] Upon working with Martin Luther King Jr., Height stated that King had once told her that Height was responsible for making The NAACP look acceptable during difficult times in the movement.[58] In his autobiography, civil rights leader James Farmer described Height as one of the "Big Six" of the Civil Rights Movement as behind the scenes and sharing the podium with Dr. King, but noted that her role was frequently ignored by the press due to sexism.[59] Height was also a founding member of the Council for United Civil Rights Leadership.

Septima Clark is most known for establishing "Citizenship Schools" teaching reading to adults throughout the Deep South.[60] These schools played an important role in the drive for voting rights and civil rights for African Americans in the Civil Rights Movement and served as a means to empower Black communities.[61] Clark's goals for the schools were to provide self-pride, cultural-pride, literacy, and a sense of one's citizenship rights. Teaching reading literacy helped countless black southerners push for the right to vote and developed future leaders across the country.[62] The citizenship schools were also seen as a form of support to Martin Luther King, Jr. in the nonviolent Civil Rights Movement.[60] Clark became known as the "Queen mother" or "Grandmother" of the Civil Rights Movement in the United States,[63] and Martin Luther King, Jr. commonly referred to Clark as "The Mother of the Movement".[64]

Abolition of Police Departments

Since the 1960s, municipal governments have increasingly spent larger portions of their budgets on law enforcement than social and rehabilitation services. Ideas to reallocate funds from law enforcement to social services were not novel in the 1960s. In 1935, W. E. B. Dubois wrote about "abolition-democracy," in his book, Black Reconstruction.[65] Activists such as Angela Davis also advocated for the defunding or abolition of police departments throughout the 20th and 21st centuries.[66][67]

Modern Movements

#Metoo

In 2006, social activist and community organizer Tarana Burke began using the phrase "Me Too" on the Myspace social network. Burke's original intention of "Me Too" was to empower women through empathy and solidarity, especially the young and vulnerable, by visibly demonstrating how many women have survived sexual assault and harassment, especially in the workplace.[68] It wasn't until October 2017 during the midst of widespread exposure of accusations of predatory behavior by Harvey Weinstein, that awareness rose after actress Alyssa Milano encouraged the use of the phrase as a hashtag.[69] Her intent was for social media to help reveal the extent of problems with sexual harassment and assault.[69] The day after Milano tweeted the hashtag, she wrote: "I was just made aware of an earlier #MeToo movement, and the origin story is equal parts heartbreaking and inspiring", crediting and linking to Burke.[68][70][71] Burke said she was inspired to use the phrase after her lack of response to a 13-year-old girl who confided to her that she had been sexually assaulted. She said she wishes she had simply told the girl: "Me too".[68]

A number of high-profile posts and responses from American celebrities soon followed, and the movement exposed several high profile men of systematic sexual abuse, such as Bill Cosby, Kevin Spacey, Harvey Weinstein, Matt Lauer. Another notable exposal included R. Kelly.

Black Lives Matter

Black Lives Matter was co-founded by three black community organizers: Alicia Garza, Patrisse Cullors, and Opal Tometi.[72][73] The movement began with the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter on social media platform Twitter after frustration over George Zimmerman's acquittal in the shooting of 17-year-old African-American Trayvon Martin in 2013.[74] Garza wrote a Facebook post titled, "A Love Note to Black People" in which she said: "Our Lives Matter, Black Lives Matter".[75] Cullors then created the hashtag #BlackLivesMatter to corroborate Garza's use of the phrase.[76] Tometi added her support, and Black Lives Matter was born as an online campaign.[75] In particular, the movement was born and Garza’s post became popularized after protests emerged in Ferguson, Missouri, where an unarmed black teenager was shot and killed by a white police officer.[77]

Cullors has acknowledged social media as responsible in exposing violence against African Americans, saying: "On a daily basis, every moment, black folks are being bombarded with images of our death ... It's literally saying, 'Black people, you might be next. You will be next, but in hindsight it will be better for our nation, the less of our kind, the more safe it will be."[78]

Garza does not think of the Black Lives Matter movement as something created by any one person. She feels her work is only a continuation of the continued historical resistance led by black people in America.[79] The movement and Garza are credited for popularizing the use of the internet for mass mobilization between activists in different physical locations; a practice called “mediated mobilization," which has since been used by other movements such as the #MeToo movement.[80][81]

#ByeAnita

Illinois State's Attorney for Cook County, Anita Alvarez was the target of Assata's Daughters and other activist organizations in Chicago during her re-election campaign because it took her a year to respond officially to the shooting death of Laquan MacDonald, who was shot and killed by Chicago police officer Jason Van Dyke.[82][83] Protesters also cited the 2012 shooting death of Rekia Boyd, a 22-year-old African-American woman, at the hands of Chicago police officer Dante Servin, with a sign that read "Justice for Rekia, No votes for Anita."[84] Alvarez had been the State's Attorney at the time and she charged Servin with involuntary manslaughter, a charge of which he was acquitted in 2015.[85]

During Alvarez's re-election bid, Assata's Daughters hung 16 banners around Chicago, to correspond to the number of bullets fired into MacDonald, with slogans such as "#ByeAnita", "#AdiosAnita 16 shots and a cover up", and "Blood on the Ballot".[84]

#MuteRKelly

.jpg)

The related campaign, #MuteRKelly was founded by Kenyette Barnes and Oronike Odeleye three months before Tarana Burke's "Me Too" message began to proliferate on Twitter in October 2017. Oronike stated, "Someone had to stand up for Black women, and if I wasn't willing to do my part — no matter how small — then I couldn't continue to complain."[86] While it took some time for #MuteRKelly to resonate with the public, on January 3, 2019, Lifetime Network aired a 6-part series titled, "Surviving R. Kelly", produced by filmmaker and music critic, dream hampton, together with Joel Karsberg, Jesse Daniels and Tamra Simmons. The first season was a critical success[87][88] and the premiere episode was Lifetime's highest-rated program in more than two years, with 1.9 million total viewers.[89] Rotten Tomatoes reads, "By unearthing previously suppressed histories, Surviving R. Kelly exposes the dangers of enabling predatory behavior and gives necessary voice to its survivors."[87]

On March 6, 2019, television program CBS This Morning broadcast an interview with Kelly by Gayle King, in which Kelly insisted on his innocence and blamed social media for the allegations.[90] Attracting media attention was an emotional outburst by Kelly during the interview where he stood up, pounded his chest, and yelled.[91]

As of July 12, 2019, R. Kelly has been accused of child pornography, kidnapping and forced labor.[92] He is currently incarcerated at Metropolitan Correctional Center, Chicago.[93]

Activists

| 19th Century | |||

|---|---|---|---|

| Sarah J. Garnet | Frances Harper | Mary Ellen Pleasant | Josephine St. Pierre Ruffin |

| Harriet Tubman | Sojourner Truth | Ida B. Wells | Henrietta Wood |

21st Century

See also

References

- Hooper, Cindy (2012). Conflict: African American Women and the New Dilemma of Race and Gender Politics. California: ABC-CLIO. pp. 44–45.

- Terborg-Penn, R (1998). African American women in the struggle for the vote:1850–1920. Bloomington,IN: Indiana University Press. p. 8. ISBN 978-0-253-33378-0. OCLC 260107480.

- Prescod, M. (1997). Shining in the Dark: Black Women and the Struggle for the Vote, 1955–1965. Amherst: University of Massachusetts Press. ISBN 978-0-585-08352-0.

- Williams, R.Y. (2008). "Black Women and Black Power". OAH Magazine of History. 22 (3): 22–26. doi:10.1093/maghis/22.3.22.

- Ogbonna, J. (2005), Black power: radical politics and African American identity, Baltimore: Johns Hopkins Univ Press, p. 105

- Williams, R.Y. (2006). Black women, urban politics, and engendering black power. In P.E. Joseph (Ed.), The black power movement: Rethinking the civil rights-black power era. New York: Routledge. p.79-103.

- "Facts about women of color in elective office". Rutgers, New Jersey: Center for American Women and Politics. 2010. Archived from the original on September 28, 2011. Retrieved July 24, 2011.

- Rosenthal, C.S. (1998). "Determinants of collaborative leadership: civic engagement, gender or organizational norms?". Political Research Quarterly. 51 (4): 847–868. doi:10.1177/106591299805100401. hdl:11244/25274.

- Wiersema, Alisa (February 1, 2013). "Reconstruction and Beyond: The 8 African-American Senators". ABC News. Archived from the original on February 13, 2013. Retrieved February 9, 2013.

- McCain, L. (1997), African American women in congress: forming and transforming history, New Jersey: Rutgers Univ Press, ISBN 978-0-8135-2353-8

- Clay, J. (2000), Rebels in law: voices in history of black women lawyers, Michigan: Univ of Michigan Press, p. 152, ISBN 978-0-472-08646-7

- "SAN FRANCISCO / D.A. creates environmental unit / 3-staff team takes on crime mostly affecting the poor". San Francisco Chronicle. June 1, 2005. Retrieved May 4, 2020.

- "Marriage Equality". Kamalaharris.org. Archived from the original on November 25, 2010. Retrieved November 18, 2010.

- "Rand Paul and Kamala Harris Team Up to Reform Bail Practices". NBC News. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "Lawmakers gather behind election security bill — at last". Politico. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "Two Women Senators Will Introduce A New Bill About Workplace Harassment". BuzzFeedNews. Retrieved April 27, 2019.

- "'She's tough': Lindsey Graham says Kamala Harris is likely Biden's vice presidential pick". MSN. Retrieved May 28, 2020.

- "Condoleezza Rice". White House. Retrieved November 14, 2008.

- "Senate Confirms Loretta Lynch as Attorney General 166 Days After Nomination". ABC news. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- Athena Jones, "Loretta Lynch makes history", CNN, April 23, 2015.

- "Loretta Lynch, Federal Prosecutor, Will Be Nominated for Attorney General". The New York Times. November 7, 2014. Retrieved November 7, 2014.

- "Obama picks NY prosecutor Lynch to be next attorney general", Yahoo! News, November 8, 2014. Retrieved November 8, 2014.

- "Loretta Lynch Is Sworn In as Attorney General". New York Times. Retrieved April 27, 2015.

- Smooth, W.G. (2010). "Standing at the crossroads". Crisis. 117 (2): 14–20.

- Romano, Lois (March 31, 2009). "Michelle's Image: From Off-Putting To Spot-On". The Washington Post. Retrieved April 4, 2009.

- Let’s Move! Archived August 20, 2011, at the Wayback Machine

- Stolberg, S.G. (January 14, 2010). "After a Year of Learning, the First Lady Seeks Out a Legacy". The New York Times. p. A20. Retrieved July 25, 2010.

- Reston, Maeve (January 21, 2019). "Kamala Harris to run for president in 2020". CNN. Retrieved January 21, 2019.

- Beckett, Lois (January 27, 2019). "Kamala Harris kicks off 2020 campaign with hometown Oakland rally". The Guardian. Retrieved July 4, 2019.

- Agiesta, Jennifer (July 1, 2019). "CNN Poll: Harris and Warren rise and Biden slides after first Democratic debates". CNN.

- Silver, Nate (August 7, 2019). "Polls Since The Second Debate Show Kamala Harris Slipping". FiveThirtyEight. Retrieved August 25, 2019.

- Harris, Kamala. "I am suspending my campaign today". Medium. Retrieved December 4, 2019.

- Beckett, Lois (July 22, 2017). "Kamala Harris: young, black, female – and the Democrats' best bet for 2020?". The Guardian. Retrieved July 10, 2018.

- Philpot, Tasha S.; Walton, Hanes (January 1, 2007). "One of Our Own: Black Female Candidates and the Voters Who Support Them". American Journal of Political Science. 51 (1): 49–62. doi:10.1111/j.1540-5907.2007.00236.x. JSTOR 4122905.

- Kaba, Amadu Jacky; Ward, Deborah E. (2009). "African Americans and U.S. Politics: The Gradual Progress of Black Women in Political Representation". The Review of Black Political Economy. 36 (1): 29–50. doi:10.1007/s12114-009-9036-4.

- tinashe (January 16, 2012). "The women's suffrage movement: The politics of gender race and class by Cherryl Walker". sahistory.org.za. Retrieved December 7, 2016.

- Smith, Robert C (2003). Encyclopedia of African-American politics. New York City: Facts On File. p. 240. ISBN 978-0-8160-4475-7. OCLC 260053829.

- Gray, D (1999). Too heavy a load: Black women in defense of themselves, 1894–1994. New York: W. W. Norton & Company. p. 42. ISBN 978-0-393-31992-7.

- Ryan, B (2001). Identity politics in the women's movement. New York City: NYU Press. ISBN 978-0-8147-7479-3.

- Freedman, R. (2006). Freedom walkers: the story of the Montgomery bus boycott. New York: Holiday House. p. 33. ISBN 978-0-8234-2031-5.

- Irvin, N. (2006). Creating black americans: african-american history and its meanings, 1619 to the present. New York: Oxford University Press. p. 317. ISBN 978-0-19-513755-2.

- Smith, B. (2000). Home girls: a black feminist anthology. New Jersey: Rutgers Univ Press. pp. 264–276. ISBN 978-0-8135-2753-6.

- Kyungwon, G. (2006). The ruptures of American capital: women of color feminism and the culture of immigrant labor. Amherst: Univ Of Minnesota Press. p. xxvi. ISBN 978-0-8166-4635-7.

- "Tired of the Oscar for Supporting Voter Role, Florida's Democratic African-American Women Take the Lead".

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/blogs/she-the-people/wp/2014/03/27/report-black-women-are-political-powerhouse-yet-remain-socially-vulnerable/

- https://www.washingtonpost.com/wp-srv/nation/BWR.Final_Black_Women_in_the_US_2014Report.pdf

- "We're Assata's Daughters". ZED Books. October 19, 2016. Retrieved February 16, 2017.

- Sullivan, C. J. (July 18, 2014). "Man dies after suffering heart attack during arrest". New York Post. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- http://www.assatasdaughters.org/our-herstory-1/

- "Chicago's New Black Power". Chicago magazine. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- Lee, Kate Linthicum, Kurtis. "How black, Latino and Muslim college students organized to stop Trump's rally in Chicago". latimes.com. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- Robnett, Belinda (May 1996). "African-American Women in the Civil Rights Movement, 1954-1965: Gender, Leadership, and Micromobilization". American Journal of Sociology. 101 (6): 1661–1693. doi:10.1086/230870. ISSN 0002-9602.

- "Coretta Scott King honored at church where husband preached". Lodi News-Sentinel. February 6, 2006.

- "Coretta Scott King".

- "Dorothy I. Height". nps.gov. National Park Service. Retrieved May 25, 2019.

- Iovino, Jim (April 20, 2010). "Civil Rights Icon Dorothy Height Dies at 98". NBC Universal. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Evans, Ben (April 20, 2010). "Dorothy Height, civil rights activist, dies at 98". Associated Press. Retrieved April 20, 2010.

- Dillard, Benita (Spring 2006). "NAACP: Helping African Americans confront social injustices for more than a century". Black History Bulletin. 69 (1).

- Farmer, James (1998). Lay Bare the Heart. Fort Worth: Texas Christian University Press. p. 215. ISBN 9780875651880. Retrieved September 22, 2014.

- Charron, Katherine Mellen (2009). Freedom's Teacher: The Life of Septima Clark. The University of North Carolina Press.

- Olson, Lynne (2002). Freedom's Daughters: the unsung heroines of the civil rights movement from 1830 to 1970 / by Fred Powledge. New York: Simon & Schuster.

- Payne, Charles. I've Got the Light of Freedom: The Organizing Tradition and the Mississippi Freedom Struggle. University of California, 1997.

- Women had key roles in civil rights movement

- Brown-Nagin, Tomiko (2006). The Transformation of a Social Movement into Law? the SCLC and NAACP's campaigns for civil rights reconsidered in the light of the educational activism of Septima Clark. Routledge.

- "Black Reconstruction :: W E B Du Bois . org". webdubois.org. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- "The Deep Roots—and New Offshoots—of 'Abolish the Police'". POLITICO. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Bakare, Lanre (June 15, 2020). "Angela Davis: 'We knew the role of the police was to protect white supremacy'". The Guardian. ISSN 0261-3077. Retrieved June 16, 2020.

- Ohlheiser, Abby (October 19, 2017). "The woman behind 'Me Too' knew the power of the phrase when she created it – 10 years ago". The Washington Post.

- D'Zurilla, Christie (October 16, 2017). "In saying #MeToo, Alyssa Milano pushes awareness campaign about sexual assault and harassment". Los Angeles Times.

- Cassandra Santiago; Doug Criss. "An activist, a little girl and the heartbreaking origin of 'Me too'". CNN. Archived from the original on October 17, 2017. Retrieved October 18, 2017.

- Milano, Alyssa (October 16, 2017). "I was just made aware of an earlier #MeToo movement, and the origin story is equal parts heartbreaking and inspiringhttps://goo.gl/mh79fF". External link in

|title=(help) - Hunt, Jazelle (January 13, 2015). "Black Lives Still Matters to Grassroots and Black Media". Black Voice News. National Newspaper Publishers Association. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- Zarya, Valentina (July 19, 2015). "Founders of #BlackLivesMatter: Getting credit for your work matters". Fortune. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- Guynn, Jessica (March 4, 2015). "Meet the woman who coined #BlackLivesMatter". USA Today. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- Ruffin II, Herbert G. (August 23, 2015). "Black Lives Matter: The Growth of a New Social Justice Movement". BlackPast.org. Retrieved December 18, 2016.

- Guynn, Jessica (March 4, 2015). "Meet the woman who coined #BlackLivesMatter". USA Today. Retrieved March 7, 2015.

- Baptiste, Nathalie (February 9, 2017). "The Rise and Resilience of Black Lives Matter". ISSN 0027-8378. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Gebreyes, Rahel (September 10, 2014). "Patrisse Cullors Explains How Social Media Images of Black Death Propel Social Change". Huffington Post. Retrieved June 2, 2015.

- "What Happened To Black Lives Matter?". BuzzFeed News. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Halpin and Hoskins, Human Rights and the Internet (2000), pp. 8–9.

- "How Black Lives Matter Changed the Way Americans Fight for Freedom". American Civil Liberties Union. Retrieved December 8, 2019.

- Rankin, Kenrya (February 24, 2016). "Young Activists Disrupt Anita Alvarez Fundraiser, Say #ByeAnita". ColorLines. Retrieved March 6, 2017.

- Ball, Jennifer (May 2016). "BLACK LIVES MATTER PUTS PROSECUTORS ON TRIAL". ProQuest 1784182715. Cite journal requires

|journal=(help) - AARONCYNIC (March 14, 2016). "Activists Hang #ByeAnita Banners Attacking Cook County State's Attorney Alvarez". The Chicagoist. Archived from the original on June 21, 2017. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- Goodman, Amy (May 18, 2016). "Rekia Boyd's Killer Resigns as Activists Call for End to "Reign of Terror" by Chicago Police". Democracy Now. Retrieved March 14, 2017.

- Sidner, Sara (February 22, 2019). "Black women would not rest until R. Kelly was investigated". lite.cnn.com. Retrieved June 8, 2020.

- "Surviving R. Kelly: Miniseries (2019)". Rotten Tomatoes. Retrieved January 11, 2019.

- "Surviving R. Kelly Reviews". Metacritic. Retrieved January 22, 2019.

- Bradley, Laura (January 4, 2019). "Surviving R. Kelly Breaks Lifetime Ratings Record". Vanity Fair. Retrieved January 7, 2019.

- "What we know about the allegations against R. Kelly". CNN. March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

the accusations of abuse, manipulation and inappropriate encounters with girls and young women have been around -- and vehemently denied -- by Kelly for decades.

- "Gayle King Commended for Leading a 'Master Class in Poise' During Raucous R. Kelly Interview". People. March 6, 2019. Retrieved March 6, 2019.

Y’all killing me with this s—!” Kelly continued emotionally, standing up. “I gave you 30 years of my f**ing career!

- Allyn, Bobby; Tsioulcas, Anastasia (July 12, 2019). "R. Kelly Arrested On Federal Charges, Including Child Pornography And Kidnapping". NPR. Retrieved July 13, 2019.

- "What charges is R. Kelly facing and how much prison time could he serve if found guilty?". Newsweek.com.