'Ubadah ibn al-Samit

`Ubadah ibn al-Samit (Arabic: عبادة بن الصامت) was a companion of Muhammad and a well-respected chieftain of the Ansar tribes confederation, who participated in almost every battle during Muhammad's era. His official title, according to Muslim scholarly tradition, was Ubadah bin Saamit al-Ansari al-Badri (Arabic: عبادة بن الصامت الانصاري البدري) for his actions at the Battle of Badr.[5] He served under the first three Rashidun caliphs in the Muslim conquest against the Byzantines.

'Ubadah ibn al-Samit Ibn Qais bin Asram bin Fahr bin Thaalbah bin Ghanem bin Auf bin (Amr bin Auf) bin Al Khazraj | |

|---|---|

عبادة بن الصامت | |

| Born | 38 B.H |

| Died | D 34 AH |

| Resting place | Jerusalem, Umayyad Caliphate |

| Known for | Battle of Badr

Battle of Khandaq Ridda wars(unspecified battles)[1] Battle of Tartus[1] Siege of Latakia[1] First conquest of Cyprus Second conquest of Cyprus |

| Family | Shamit Ibn Qais Ibn Asram Ibn Fahr(Father)[2] Qarat al-Ain Bint 'Ubadah bin Nidhal al-Khazrajiyya(Mother)[3] Umm Haram(wife) Jamilah bint Abi Sa'sa(wife)[4] 'Aws ibn al-Samit(brother) Nussaybah Bint al-Samit(sister) Ubaydah ibn 'Ubadah(son) Walid ibn 'Ubadah(son) |

| Part of a series on |

| Islam |

|---|

|

|

The conquer of Cyprus marked al-Samit as one of the most successful military commanders in the history of the Rashidun army. He participated in at least seven large scale military campaigns during his life before ending his career as a Qadi in the Holy Land. In his later years he assisted the then-governor Umayyad Caliph Muawiya I. In general, Islamic scholars regard al-Samit as an influential companion of Muhammad that passed down many hadiths which became the basis of Fiqh ruling in various matters.[6][1]

Life in Yathrib

Early life

Al-Samit was a descendant from Yemeni Arabs that settled in Yathrib, who formed the Banu Aws and Khazraj tribes. He was born into the latter and became a prominent chief.[7]

Pledge of Aqaba

Sometime before Muhammad's migration from Mecca, al-Samit and other Banu Aws and Khazraj tribe chieftains, such as Abdullah ibn Rawahah, ʿAbdullah ibn Haram, Sa'd ibn Ubadah, and Abu Talha al-Ansari met Muhammad on Mount Aqaba during their journey from Medina to perform Hajj in Mecca. In historical literature, these clan leaders are said to have done Hajj to achieve enlightenment after they grew weary due to the conflicts that were happening between their tribes, particularly the civil war of Yathrib which Muslim historians called the Battle of Bu'adh, Muhammad praised Islam to any Hajj pilgrims he met. They listened to his preaching until considered him to be the solution to unite their conflicting tribes in Medina. They immediately pledged their allegiance to him, marking this event as the first pledge of al-Aqabah. Al-Samit was around forty years old.[8][9]

Later he also participated in the Second pledge at al-Aqabah, where 'Ubadah narrated the event

I was among those who were present at Aqabah. We were twelve men who took an oath of allegiance to the Messenger of Allah Shalallahu Alayhi Wassalam in the Pledge of Aqabah, which was called Bai'at An-Nisa'[Notes 1](,) This was before the fighting was enjoined, so we pledged not to associate anything with Allah, not to steal, not to commit adultery, not to kill our children, not to intentionally forge falsehood[Notes 2], and not to disobey him in any just matter. "If you fulfil that then Paradise will be yours, but f you commit any of these sins, it is for Allah to forgive or punish as He wills'[11] "

When the Meccan Muslims were migrating to seek refuge in Yathrib (now Medina), al-Samit and his fellow Banu Aws and Khazraji provided shelters to the Meccan Muhajireen (refugees). Muhammad instructed al-Samit to take an oath of brotherhood with the Muhajireen, named Abu Marthad al-Ghanwi.[12]

Battles under Muhammad

Battle of Badr

During Muhammad's stay in Yathrib, al-Samit participated at the battle of Badr, which elevated his status as a patron of Islam in a view of both early and contemporary Muslim scholars and earned him the title of al-Badri, which is bestowed to Muslims who attended the battle.[5][1] Al-Samit gave his testimony in regards to the aftermath of the battle when the Muslim army discussed their prisoners of war.[5]

Later, al-Samit, who was one of the Ansar tribe chiefs, announced that he annulled the alliance with the Jews of Banu Qaynuqa due to an accident happened between them and Muhammad after the revelation of verses 51 and 52 of Al Ma'idah from Muhammad. Al-Samit's position as the respected head clan superseded Abdallah ibn Ubay's (another Khazraji chief) support of the Jews. In the end, the entire clan instead followed 'Ubadah and supported Muhammad. Al-Samit expelled the Banu Qaynuqa Jews from Medina and took their date palm gardens as loot for the city's Muslim community before continuing to serve in the Battle of Khandaq.[13]

Accident during raid on Banu Mustaliq

The Ansaris under al-Samit and his colleague, Sa'd ibn Ubadah, numbered 627 in a January expedition against the Banu Mustaliq tribe. The raid was successful and they took 200 families captive, 200 camels, 5,000 sheep, goats, and a large quantity of household goods.[14] However, there was an accident during the battle where al-Samit unintentionally killed one of his Ansari clansmen, Hisham ibn Subabah.[15]

Sometime after the treaty of Hudaybiyya, al-Samit fought in the battle of Khaybar.[1] He virtually participated in all battles under Muhammad before the prophet's death.[13]

Writer of the Qur'an

Muhammad ibn Ka'b al-Qurazi narrated that during the time of Muhammad, al-Samit was among those who collected and wrote down the Qur'an along with Muadh ibn Jabal, Abi ibn Ka'b, Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, and Abu Darda.[16]

Service under Rashidun caliphate

| Caliphate خِلافة |

|---|

|

|

Main caliphates |

|

Parallel caliphates |

|

|

After Muhammad's death, the Medinan Ansaris including al-Samit along with the Meccan Muhajireen discussed matters regarding who should continue the leadership of the still-young Muslim community as the first caliph. At first al-Samit and his clansmen nominated Sa'd ibn 'Ubadah, but the Muhajireen nominated Abu Bakr instead. The Ansaris conceded and agreed to select Abu Bakr as the caliph to lead the overall Islam authority, causing the progress of the Muslim leadership election goes smoothly in Muslim citadel.

Under Caliph Abu Bakr

After the selection of the first caliph, rebellion broke out in almost all of the caliphate. Al-Samit was commanded by Caliph Abu Bakr to quell the rebellions across Arabia, though it is not specified which battles he was involved in.[17][18]

Under Caliph Umar

According to David Nicolle, the four Rashidun contingents left Medina between the autumn of 633 to 634 before Khalid converged with other contingents led by generals such as Abu Ubaydah ibn al-Jarrah, Yazid ibn Abu Sufyan, Amr ibn al-A'as and Shurahbil Ibn Hasanah.[19] Al-Samit, Abu Darda, and Muadh ibn Jabal were sent to Syria after ibn Abu Sufyan asked the caliph to send him preachers who can teach the newly subdued Christian population in Syria. At some point, al-Samit was tasked to assist the military campaigns in Syria due to his military prowess.[1][12]

Campaign in Levant

During the time of Caliphate Umar ibn al-Khattab, there was a request for reinforcement from the Syrian front during the Rashidun's conquest of Levant. Khattab sent al-Samit to join forces with Abu Ubayda ibn al Jarrah and Khalid ibn al-Walid.[1]

Battle of Ajnadayn

Waqidi recorded al-Samit's participation in the Battle of Ajnadayn where he led a small decoy squad consisted of women and children to deceive the Byzantine army. They lured them before the main army led by Khalid ibn Walid.[20] The 100,000 Byzantine soldiers under Vardan were trapped as they were defeated and fled to Damascus. This battle ended with more than half of the Byzantine army killed, including their general, Vardan.[21][22]

Homs

In the Siege of Emesa between 635 and 636 AD, after the Muslim armies successfully occupied Homs, Abu Ubaydah appointed al-Samit as his deputy in Homs while Abu Ubaydah left to capture Hamah. Al-Samit stayed there with his wife, Umm Haram.[23] Bukhari reported that he heard Umair ibn Aswad al Ansi was once told by Umm Haram that Muhammad spoke with her:

She said: “Messenger of God, pray for me that I will be one of them.”

He said: “You are one of them.” He soon was asleep again. Once more he woke up smiling and she asked him why he was smiling. His answer was the same as he gave her the first time. Again she asked him to pray to God to make her one of them.

He said: “No. You will be among the first ones.”[24]

Similar narration was also given by 'Umair ibn Aswad al-Ansi who has been told by Umm Haram.[12]

Further record came from the testimony of an Abd al-Rahman al-Awza'i, a Tabi'un and founder of now extinct Awza'i Madhhab. Imam Awza'i saying that al-Samit was the first Wali or Caliphate Governor in Palestine.[4]

Yarmouk

Waqidi noted in his chronicle of the conquest of Sham that al-Samit also participated in the Battle of Yarmouk. Heraclius sent a messenger to Vahan and ordered him not to start the war with the Muslims until he sent a messenger to them promising that he would annually send money and gifts to their Commander Al-Khattab and to all their Amirs and that they can have all that is between Al-Jaabiya and Al-Hejaz.

Vahan sent Jabalah ibn al-Aiham, ruler of Ghassanid to negotiate for the second time as Vahan thought only an Arabs could reach out to negotiate with their kinds. al-Aiham approached the Muslims as an envoy and threatened the Muslims to retreat and abandon their intention to go war with the Byzantines, as the Byzantines had about 200,000 men that consisted of Greeks, Slavs, Franks, Georgians, Armenians and Christian Arabs, while guaranteeing safety if they desisted.[25] Instead, Abu Ubayda sent al-Samit, replied to al-Aiham in confidence that the Muslims did not intent to abandon their intention from conquering Byzantine territory in the Levant:

Ubada ibn Al-Samit said

Oh Jabla. Don't you know how we faced your advanced forces at Ajnadain and other places and how Allah Subhanahu Wa ta 'Ala granted us victory over you and how your tyrant ran away? We know who remains from your forces and they are easy for us. We are not afraid of these forces that have come. We have tasted blood and we haven't found blood sweeter than the blood of the Romans! Jabla, I call you to the religion of Islam and to enter our religion with your people and keep your honor in this life and the next life. do not be a servant of these uncouth Romans and put your life on the line to save them from destruction. You are from the chiefs of the Arabs and a king. Verily our religion has appeared. Follow the path of those who have repented and returned to Allah and believe in Him and say: There is no God but Allah and Mohamed is the Messenger of Allah…'[25]

When they defeated the Byzantine coalitions in Yarmouk, al-Samit, along with the army of Abu Ubayda and Khalid, continued their conquest until they reached the outermost of Northern Syria, where they turned south to pacify the shore areas of Levant. Al-Samit was sent to subdue Tartus, a coastal fortress city.[26] While al-Samit occupied Tartus, Muawiyah came to the city, fortified the town further, and gave fiefs to the garrison commanders.[27]

Latakia

After Tartus was subdued in 636, al-Samit was commanded by Abu Ubayda to march towards Jablah and Laodicea (Latakia).[28][29][1]

Al-Samit met with resistance from the local garrison during the siege of Latakia. He observed that the city had a massive gate that could only be opened by a large number of men. He ordered his men to camp at a distance and dig trenches which could hide a rider on horseback. Al-Samit and his army pretended to return to Homs during daylight, while at night he ordered the army to return hide themselves inside the trench. As soon as people in Laodicea thought al-Samit left, they opened the gate to let their cattle out.

Al-Samit immediately ordered his entire army to launch the attack. the Byzantines were caught by surprise and failed to close the gate before al-Samit and his army entered. He climbed the wall then shouted a takbeer battlecry which, bolstered by his soldiers, terrified the Byzantine defenders to flee towards Al-Yusaiyid.[27]

The fleeing Byzantine soldiers and local citizens returned and surrendered to al-Samit, who accepted their surrender and allowed them to return to their homes with specific conditions, including the obligation to pay the Kharaj land tax.[27]

Al-Samit did not raze any buildings including churches, but started to build mosques and took stayed for a while to impose the order of the caliphate to the subdued population. One particular mosque, Jami' al Bazaar or Mosque al-Bazaar stands to the current day. Laodicea was renamed to Latakia or Al-Ladhiqiyah.[26][30]

Caesarea

Al-Samit joined the main force of Muawiyah to conquer Caesarea in 640 and was appointed to lead the Right Flank of the Muawiyah corps during the last battle against the Romans at Qaysariyyah or Caesarea Maritima. The Muslims were repelled several times before al-Samit and several of his men rushed the Byzantine ranks in a single charge and broke the stalemate. The Muslim armies achieved complete victory against the historical territory of Byzantine which led to the formation of the Jund Filistin military district of the caliphate and ended al-Samit's journey in the Levant.

During this time, al-Samit was appointed as the first governor of Jund al Filistin.[31][29][1]

Transferred to Egypt

In July 640, during the siege of Babylon fortress in Egypt against the Byzantine forces, al-Aas wrote to al-Khattab to ask for reinforcements. Al-Khattab sent a reply with an accompanying army.

I have sent you a reinforcements [sic] of 8.000 warriors. It consist of 4.000 mens [sic], each of 1000 was led by four figures wherein each of these men strength are equal to 1000 mens [sic]'[32]

Those 4 commanders were two veteran Muhajireen, Zubayr Ibn al-Awam and Miqdad ibn al-Aswad; a young Ansari commander named Maslama ibn Mukhallad al-Ansari; and al-Samit. These reinforcements arrived at Babylon sometime in September 640.[1] Imam Awza'i also recorded that he witnessed the Muslim conquest of Egypt where he confirmed that al-Samit was among those who were sent to aid al-Aas.[4]

Battle of Heliopolis

Amr ibn al-Aas decided to take the Byzantine to battle on the open field near Heliopolis in early to mid July 640. The 8,000 al-Aas soldiers were led by al-Awam, al-Samit, Maslama, Miqdad, Bisr ibn Abi Artat and defeated the 20,000 strong Byzantine army under Theodore.[33][34]

Siege of Babylon fortress

The Muslims under al-Aas besieged the fortress of Babylon over the course of months without a clear victory. During the siege, both sides exchanged envoys in an effort to demoralize each other.[1] In the days leading up to the end of the siege, al-Samit was sent to give a delegation to Muqawqis to negotiate for the last time. It is said that Muqawqis became afraid of al-Samit when he saw al-Samit's dark and majestic appearance. Ubadah then mocking Muqawqis in written chronicle:

Truly there are 1000 of my comrades behind me. They are peoples who have darker skin than me and more sinister than me. if you saw them you would be more scared than you see me. I was appointed (as the leader) and my youth had passed. and praise be to Allah. You know, I'm not afraid if 100 of your people face me alone at once. so are my comrades behind me[1]

Al-Samit gave him three options: accept Islam, pay Jizyah, or fight it out in accordance with al-Aas' instruction. It is said that Muqawqis, after the negotiation ended, spoke to his aide regarding al-Samit:

I was afraid of that man's appearance. But I'm more afraid to the way he talks. [1]

Following consultations, the Byzantine forces decided to fight, and on the same day the fortress fell to the Muslims led Zubayr ibn Awam who climbed the fortress wall alone and opened the gate from inside.[1]

Siege of Alexandria

After the fortress has been taken, al-Aas consulted with Maslama ibn Mukhallad. Mukhallad suggested to al-Aas to give a field command to al-Samit to attack Alexandria. Al-Samit rode to al-Aas, who gave him his spear of command.[35] Al-Samit rode toward the army and gave a speech before commencing his attack on Alexandria.[36]

Al-Samit led a detachment to besiege Alexandria on the same day and reused his strategy of using trenches to ambush Latakia in the past. When he and his main force has arrived at the outskirt of Alexandria,he gave a signal to the entire army including those who hid in the trenches to launch an assault. His attack successfully breached and routed the Alexandrian garrison forces on the very first charge.[12]

After the conquest of Alexandria, al-Samit stayed in Egypt to help al-Aas build the city of Fustat and its landmark, Mosque Amr ibn al-Aas.

Campaign of Anatolia

Shortly after al-Samit completed his tasks in Egypt, he was dispatched by Caliph Umar to assist Muawiyah I to attack Amorium in the winter of 644 with a force of 10,000.[37] This campaign continued northwards until Muawiyah reached an area in Anatolia called Shaifa.[37].

Becoming a judge in Palestine

At some point during the last years of al-Khattab's life, he wanted to appoint al-Samit as a governor permanently in Homs reasoning that the grip of the caliphate and the influence of Islam was still new in that area, so he needed someone he strongly trusted to impose strict order in the newly conquered area.[13] Al-Samit declined the offer until he agreed instead to be appointed as Qadi in Palestine. Al-Samit also spent his time during his tenure as Qadi to teach people the Quran and hadith, open a public Majlis[13] and lead sermons in Palestine.[38][1]

Under Caliph Uthman

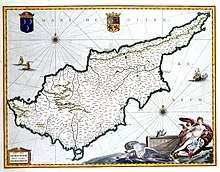

First Conquest of Cyprus

After Uthman ibn al-Affan became the new caliph after Umar's death, Muawiyah requested that the caliph allow him to build a navy to attack Cyprus, as Muawiyah reasoned that Cyprus has become a satellite island of Byzantine forces which can threaten the caliphate on the western banks of Palestine.[39]

Al-Samit, along with some veteran companions of Muhammad such as Miqdad Ibn al-Aswad, Abu Dhar GhiFari, Shadaad ibn Aws, Khalid bin Zayd al-Ansari, and Abu Ayyub al-Ansari, also participated in building the first Naval armada of the caliphate led by Muawiya.[40][41] Before he joined Muawiya project to built first naval forces of the caliphate, al-Samit joined forces with another Muslim general, Abdallah ibn Qais. Together with Muawiyah they built the first caliphate naval armada with Muawiya in Acre with permission from al-Affan. Abu Dharr also mentioned another big name, Miqdad ibn Amr al-Aswad also participated in this expedition to Cyprus Island.[42]

Shortly, Muawiya and al-Samit departed from Acre and headed to Cyprus.[43]

According to al-Baladhuri and Khalifa ibn Khayyat, Mu'awiya and al-Samit led the attack were accompanied by their wives Katwa bint Qaraza ibn Abd Amr of the Qurayshite Banu Nawfal and Umm Haram respectively. Umm Haram narrated the prophecy of Hadith which she believed related to this campaign. Anas ibn Malik, her nephew, quoted Muhammad's words hadith:

The Prophet visited us and there were only me, my mother (Umm Sulaym) and my maternal aunt (Umm Haram). He said: ‘Let us pray in congregation’. No obligatory prayer was due. He led us in prayer. When we finished he prayed for us, members of our household, appealing to God to grant us of every good thing in this life and in the life to come. [24]

Muawiya and al-Samit's forces pacified almost every Byzantine garrison; there were at least 50 military operations that occurred in Cyprus between this first campaign in 648 until the last one in 650[39], supported by the evidence of two Greek inscriptions in the Cypriot village of Solois that cite the occurrence of those two offensives.[44] The entire island of Cyprus surrendered for the first time after their capital, Salamis, was surrounded and besieged for an unspecified time. However, Umm Haram died in an accident during the campaign.[39].

Muawiyah and al-Samit accepted Cyprus' surrender under the condition that they refrain from being hostile to the Muslims, inform the caliphate of any Byzantine movements, pay 7,200 dinars annually for Jizya, and never reveal any information to outsiders regarding the caliphate military operations.[39]

Second conquest of Cyprus

In 652, the Cyprus island rebelled against the caliphate and caused Muawiyah and al-Samit to mount the second campaign on the island.[39].

This time Mu'awiyah and al-Samit split their forces into two: one led by Mu'awiyah and the other by Abdallah ibn Sa'd. This punitive campaign was described in Tarikh fi Asr al-Khulafa ar-Rashidin as particularly brutal as many died in the campaign and many men from the Cyprus forces were taken captive.[39].

When they pacified Cyprus for the second time, al-Samit said to Mu'awiyah:

I have heard Rasulullah Shalallahu alaihi Wassalam at the battle of Hunayn, that time, peoples asking for booties and spoils to him. Then he took a fur of camel and saying:

'I did not have rights for the spoils of war which given by Allah except a fifth of it. and the fifth of it will be returned to all of you'

so, obey Allah, o Muawiyah. Share the spoils with just and fairness. do not give someone more than his rights[39]"

Muawiyah gave al-Samit the task to manage the spoils of war. Afterwards, Muawiyah consulted with one of his officers, Ismail bin Ayyasy, as to how to prevent another uprising. Muawiyah decided to place a garrison of 12.000 soldiers to guard Cyprus. Muawiyah also transferred portions of Muslim settlers from Baklabak, Syria, to Cyprus while also constructing mosques to help Islamization on the Island.[39]

Later, the Muslim forces accepted the Cyprus' surrender and spared them as they paid Jizya to the caliphate. This campaign set a precedent for the more successful second campaign many years later after al-Samit's death in the Battle of the Masts, known to Muslim historians as the Battle of Dhat al-Shawary, where the first Muslim naval forces won against the Byzantine mariners.[43]

Later life and death

At the end of his military career, al-Samit retired to Palestine.

When Caliph Uthman faced dissidents from the Khawarij sect and portions of the followers of Abdullah ibn Saba, al-Samit was among those who expressed his support towards Caliph Uthman. Al-Samit did not appreciate the revolts from the Abdullah ibn Saba followers, which was headed by Yazid ibn Qais and Malik al-Ashtar against the caliph.[45] He, Mu'awiyah, Kharijah ibn Huzafah of Egypt, Anas ibn Malik, Hisham ibn Amir, Abu Darda, and Tabiin were among those from outside Medina who urged the caliphate army to take action against the Khawarij dissidents in Medina.[42]

Al-Samit died in Ramla in age of 72.[46][47][48] He said on his deathbed:

By Allah, every Hadith (from the Prophet) which I heard from Rasulullah Shalallahu Alaihi Wassalam. I will tell you because not long time before i leave this world, i will tell one Hadith. I have heard that Rasulullah Shalallahu Alaihi Wassalam has said: "Whoever testifies to that there is no God besides Allah and Prophet Muhammad is messenger of Allah, then Allah will forbid the hellfire to (burn) him. [50]

Personal life

Physical appearance

Dr. Khalid Basalamah Lc, MA, interviewed the Imam of Al-Aqsa mosque during a visit to al-Samit's grave in Palestine. The Imam described through the oral tradition which has been passed through generations in Palestine that al-Samit was a "handsome man with dark skin".[1] This was also supported by Ibn Hajar in his Siyar A'lam Nubala in the chapter of al-Samit where he describes him as physically attractive.[51]

The Imam noted al-Samit was "very muscular. So ripped and huge the Ansari is that his forearm size is equal to the span of [an] adult male hand palm."[1]

Several historians noted how his enemies, such as Muqawqis, governor of Egypt and Jabalah and leader of the Ghassanid Arabs in the battle of Yarmouk were struck in awe by al-Samit's appearance.[1]

Family

Al-Samit had a sister named Nusaybah.[7] His father was Shamit Ibn Qais Ibn Asram Ibn Fahr while his mother was named Qarat al-Ain Bint 'Ubadah bin Nidhal al-Khazrajiyya. His brother, 'Aws bin al-Samit, was married to Khawla bint Tha'labah, a female companion of Muhammad who was mentioned in Surah al Mujadalah.

Records from Bukhari and Muslim texts has written the words from Anas Ibn Malik that al-Samit was married to Umm Haram bint Milhan during the first conquest of the Island of Cyprus with Muawiyah when Umm Haram died during the campaign. Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani translated this to mean al-Samit just married Umm Haram during the campaign. However, Ibn Ishaq disagreed and translated the words of Anas to mean Umm Haram was already married to al-Samit before the campaign. Ibn Hajar argued further that there is another record from Ibn Hibban that Umm Haram just married to al-Samit, which caused Dr. Ibrahim al Quraibi, author of Tarikh ul-Khulafa, to side with Ibn Hajar.[52]

Al-Samit was also married to Jamilah bint Abi Sa'sa' and they had a son named Walid ibn 'Ubadah.[4]

His son, Ubaydah ibn 'Ubadah ibn al-Samit, was buried in Egypt.[53]

Character assessment

Al-Samit was known as a fearless warrior on the battlefield. He was once recorded for displaying his personal military prowess when the Muslims had besieged a Byzantine fort. Ubadah was found alone praying in a field by Byzantine soldiers. Before they could approach, he jumped to his horse and advanced towards them. The Byzantine soldiers fled and were chased by al-Samit until they reached their fort.[35]

Al-Samit was also known as a clever commander who deployed successful strategies to situations, such as the use of ambush trenches which allowing him to successfully beat difficult strongholds such as Latakia in Syria and Alexandria in Egypt.

Historians described al-Samit as a stern man with high confidence who could not be easily intimidated by his enemies during negotiation as demonstrated before the Siege of Alexandria and before the battle of Yarmouk.

Al-Samit was known as a solemn person who detested sycophants. He once attended a Friday prayer in Damascus where the khatib of the sermon prayer lauded him with praise when al-Samit was a chief judge. He threw mud in the Khatib's face and quoted Muhammad:

Did not the Prophet, Peace and Allah blessing belong upon him, said that when we saw a person extolling virtues to his face, then we should throw mud to his face?[54]

Despite this difficult attitude, Caliph Umar held al-Samit in high regard. The caliph respected him to the extent that he favored al-Samit by giving him many important tasks during his time as caliph. Caliph Umar once also praised him as a man comparable to 1000 soldiers in quality during the campaign in Egypt. This gesture is analyzed by scholars to describe how the caliph held al-Samit in high confidence to do the impossible.[1]

In another occasion, Caliph Umar supported al-Samit when the latter came into conflict with Muawiyah. In response, the caliph appointed al-Samit as Qadi while giving him a degree of autonomy so that Muawiyah, who was the governor of Syria at the time, could not interfere with any verdict passed by al-Samit.[1]

Legacy

| |

|---|

|

|

|

|

Lists |

|

|

Dr. Khalid Basalamah said the prominence of al-Samit in the conquest of Egypt and Levant are noted by Middle Ages and contemporary historians, who praise him as a patron of the Qur'an, Hadith, and science as well as a venerable military figure whose contribution to the spread of Islam in Syria, Palestine, and Africa is almost incomparable. To this day his presence is revered by many Palestinian Arab communities who preserve his tomb in Ramla, Palestine.

Historical book author Simon Sebag Montefiore writes the keeper of al-Samit's tomb today hails from the Nusaybah clan, a modern Arabic generation that claims to be descendants of both al-Samit and Nusaybah, sister of al-Samit.[55] the Palestinian Arabs in general also regard him as an influential figure as evidenced by the public sermon by Dr. Yusuf Juma Salama, one of the official khattib of Al-Aqsa Mosque that also spoke of al-Samit as the first judge of Palestine.[56]

Architecture

Al-Samit demonstrated his skill as an architect after the conquest of Latakia. When he administered the city, he built the Great Mosque of al-Bazaar. The mosque has two western entrances. South of the mosque leading to the courtyard of the mosque is an open space recently roofed with raspberry boards, and follows the intended bowl from the eastern side, two open spaces open in front of the mosque is a rectangle covered with six stone arches, and a medium-sized minaret of the mosque stands on its highest base. The mosque does not contain any urban artistic touches except for some decorations on the entrance and the minaret. On the western side of the mosque is an old bathroom. Until 2 April 2009, the mosque was headed by Imam Professor Bilal Shaheeri.[57]

Another example of his architecture expertise is when he ended the conquest in Egypt With al-Aas. He was involved in planning and developing Fustat and was also involved in constructing the first mosque in Egypt which exists to this day, known as the mosque of Amr bin al-Aas. He, along with some prominent companions of Muhammad such as Zubayr ibn Awam, Abu Darda, and Miqdad ibn Amr al-Aswad, also constructed and decided the Qibla or direction of prayer of the mosque.[58][1]

Quran

Quranic exegesis experts generally accept al-Samit's participation in the Pledge of the Tree are Asbab al-nuzul of the verse 55-56 of Al-Ma'idah, which is one of the factors that 'Ubadah are venerated in the Muslims community.[1]

Furthermore, tradition from Al-Tabarani and bayhaqi agreed the revelation of verse 51 to 52 of Al Ma'idah also linked with 'Ubadah. Where the verses reprimanded 'Ubadah to not follow the path of hypocrite like Abd-Allah ibn Ubayy who taking companionship from heretics like Jews and Christian.[59]

Hadith

Ibn Hajar in his book, Siyar a'Lam Nubala, recorded there are at least one hundred and eighty-one hadiths.[51]

The Muslim scholarly community generally remembers al-Samit as a Sahaba that passed down many hadith narrations from Muhammad, many of which became the basis for many fiqh rules in Sunni Madhhab.[6][1] One of the most famous hadiths was from Muhammad telling Umm Haram in regards to the prophecy that the Islamic caliphate will dominate the sea on two occasions. The general consensus of the Muslim scholars has thought this hadith are referencing the First conquest of Cyprus and the second campaign which followed years later, where al-Samit participated in both campaigns.

Muslim scholars of Sunni Maddhabs quote a hadith passed down by al-Samit:

We are taking the pledge to the Prophet of Allah, Peace and Prosperity belong upon Him, to listen and obey, whether we like it or dislike it, whether it's about matters we fond of or matters we did not fond of it and make us being selfish, and to not revoke mandates to those who have the right for it, So it will cause us to say the right thing wherever we go. and so we did not feel scared when we go to fight in the path of Allah

Maddhab scholars from Hanafi, Hanbali, Shafii, Maliki and other smaller and extinct Madhhab schools like Madhhab of Sufyan al-Thawri have taken this hadith as a basis of Sharia law regarding governorship and conduct of ruling that loyalty and obedience to the rightful rulers or leaders are a part of Muslim obligation.[52]

Another example of a hadith from al-Samit which has been used as the basis for Madhhab scholars is one said by Ibn Shihab al-Zuhri which he attributed to al-Samit through Mahmud ibn al-Rabi that he said he heard Muhammad saying:

There is no Salah (prayer) for those who did not recite al-Fatiha (opening) Surah of the book.

This hadith has become a basis of Fiqh scholars to formulate the ruling that al-Fatiha are obligatory to be recited in every Salah ritual for Muslims.[60]

A specific hadith from al-Samit was also attributed as a metric by Muslims to measure the existence and omen of Laylat al-Qadr, which is held in high importance in their faith:

That night was a bright, bright night, as if there was a moon, a calm and peaceful night, neither cold nor hot. On that night no stars were thrown until the morning. And indeed, the sign of Laylat al-Qadr is, the sun in the morning rises beautifully, does not shine strongly, like a full moon, nor is it permissible for the devils to go out with the morning sun

— Imam Ahmad Bin Hanbal[60]

Scholarly view

Aside from being one of the primary sources of hadith, Sunni scholars classified al-Samit as being among the higher-ranked Companions of the Prophet, due to his heritage as an Ansari and his attendance in the First and Second Pledges in Aqaba, the Battle of Badr, and the Pledge of the Tree.[61][1]

The earliest Muslim scholars record Imam Ahmad also supported al-Samit's venerated status as evidenced from Ahmad ibn Hanbal.[62] His status as a veteran of Battle of Badr is particularly special in the eyes of scholars as Muhammad has regarded those of his companions who attended Badr as among the most important in Islam.[5]

Ibn Hajar al-Asqalani listed a specific chapter of personal biography of 'Ubadah bin al-Samit in his Siyar a'lam Nubala.[51]

See also

Sources

Primary source

- Bukhari; Sahih Bukhari

- Muslim; Sahih Muslim

- Bayhaqi; Sunan Bayhaqi

- Al-Tabarani

- Tarikh at Tabari

- Ibn Hajar; Siyar A'lam Nubala

- Baladhuri; Futh al Buldan

- Waqidi; Futuh as-Sham

- Ibn Hisham;

- Ibn Kathir; al-Bidayah wan-Nihayah

- Ibn Abdul Hakam; Futh al Misri wal Akhbaruha

Notes

- It was called Baiat an Nisa, or Pledge of the Women, because of the presence of 'Afra bint 'Ubaid ibn Tha'labah, who was the first women to swear an oath of allegiance[10]

- Referencing Al-Mumtahanah verse 12

References

- Basalamah, Dr. Khalid Zeed Abdullah. "Seerah Sahaba". Khalid Basalamah Official website. Khalid Basalamah official. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "الكتب - سير أعلام النبلاء - الصحابة رضوان الله عليهم - عبادة بن الصامت- الجزء رقم1". islamweb.net.

- "الطبقات الكبرى ط العلمية". Archived from the original on 2017-04-06.

- "تقريب تحفة الأشراف 1-5 - 4". IslamKotob – via Google Books. Alt URL

- "Badar al-Kubra, dispute regarding prisoners of war". Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Sulaymān ibn al-Ashʻath al-Sijistānī, Abu Dawud (1984). Sunan Abi Dawud. Sh. M. Ashraf. p. 1012. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Sebag Montefore, Simon (2012). Jerusalem: The Biography. Pustaka Alvabet. p. 226. ISBN 978-6029193022. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- "The Second 'Aqabah Pledge", The Sealed Nectar, Sunni path

- Abd Allah ibn Rawaahah, Islamic council, archived from the original on 2006-06-30

- Atlas Al-sīrah Al-Nabawīyah. Darussalam. February 1, 2004. ISBN 9789960897714 – via Google Books.

- Abu Khalil, Shawqī (2004). Atlas Al-sīrah Al-Nabawīyah. Darussalam. p. 292. ISBN 9960897710. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Ahmad Ghadanfar; Al-Khaiat, Mahmood ; Dr. Abdul-Latif (2001). The Commanders of Muslim Army. Darussalam Publishers. p. 392. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Gil, Moshe (1997-02-27). Ibn Sa'd, 1(1), 147 VII(2), 113f, Baladhuri, Tarikh Tabari, 1 2960, Muqaddasi, Muthir, 25f; Ibn Hisham, 311. Cambridge University press. p. 119. ISBN 0521599849. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Mubarakpuri, Saifur Rahman Al (2005), The Sealed Nectar: biography of the Noble Prophet, Darussalam Publications, pp. 386–387, ISBN 9789960899558 (online)

- Ahmed Ali Abdel-Qader Muhammad al-Maqrizi, Taqi al-Din. "Battle with Banu Mustaliq". With prophet. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Shaban, Ahmad. "عبادة بن الصامت.. تبرأ من حِلف قديم". Al Ittihad.

- Basalamah, Dr. Khalid Abdullah Zeed. "Seerah Abu Bakr session 3 public lecture". Youtube. Khalid Basalamah official. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Basalamah, Dr. Khalid Abdullah Zeed. "Seerah Sa'd ibn Ubadah public lecture". Youtube. Khalid Basalamah official. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- D. Nicolle, Yarmuk 636 AD - The Muslim Conquest of Syria, Osprey, 1994, p. 46.

- Muḥammad ibn Jarīr al-Ṭabarī, Abū Jaʿfar. "Tarikh at-Tabari; Futuh as Sham/Conquest of Sham; Vol. 4". Ummah. Salman-al-Farisi account. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Gil, Moshe (1997). A History of Palestine, 634-1099 quoting Baladhuri. Cambridge University Press. p. 1485. ISBN 0521599849. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Gibb, H.A.R. (1986). "Ad̲j̲nādayn". The Encyclopedia of Islam, New Edition, Volume I: A–B. Leiden and New York: BRILL. p. 208. ISBN 90-04-08114-3.

- al-Quraibi, Ibrahim; Afkar, Dahyal (2016). Tarikh al-Khulafa. Qisthi press. p. 502. ISBN 978-9791303408. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- al-Bukhari, Sahih. "Sahih Bukhari Book 56, Hadith 7". Sunnah. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- ibn ʻUmar Wāqidī, Muḥammad (2005). Futuhusham. Ta-ha. p. 389. ISBN 1842000675. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- K. Hitti, Phillip. "The origins of the Islamic state : being a translation from the Arabic". COLUMBIA UNIVERSITY. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Bin Yahya Bin Jabir Al Baladhuri, Ahmad; Kuri Hitti, Phillip (March 2011). The Origins of the Islamic State: Being a Translation from the Arabic Accompanied With Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitab Futuh Al-buldan. Cosimo inc. ISBN 9781616405342. Retrieved 29 January 2020.

- Taha al-Salmani, Dr. Abdullah. "ملخص البحث". Philadelphia education. University of Mosul. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Bin Yahya Bin Jabir Al Biladuri, Ahmad (March 2011). The Origins of the Islamic State: Being a Translation from the Arabic Accompanied With Annotations, Geographic and Historic Notes of the Kitab Futuh Al-buldan. Cosimo, Inc. ISBN 9781616405342. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- al-Zibawi, Mahmud. "لاذقية العرب(Arabic Lattakia)". Maaber. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Taha al-Salmani, Dr. Abdullah. "ملخص البحث". Philadelphia education. University of Mosul. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Saleh, Qasim a Ibrahim dan Muhammad A. (2014). Buku Pintar Sejarah Islam (in Indonesian). Serambi Ilmu Semesta. ISBN 978-602-17919-5-0.

- Siyar A'lam Nubala, Ibn Dhahabi. "عمرو بن العاص رضي الله عنه داهية العرب.. فاتح مصر". ـ موقع الشيخ حمد الحقيل. Laha Online. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Hasson, Isaac (2019) [2011]. "Busr b. Abī Arṭāt". In Fleet, Kate; Krämer, Gudrun; Matringe, Denis; Nawas, John; Rowson, Everett (eds.). Encyclopaedia of Islam, THREE.

- Musthofa Saad , Abu Amir Al-Humaidi, Mahmud , Dr. Nashir (2017). Golden Stories: Kisah-kisah Indah dalam Sejarah Islam. Pustaka AL-Kautsar. p. 444. ISBN 978-9795926436. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- "PENAKLUKAN MESIR DAN ALEXANDRIA; Bab III". digital library. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Andi Bastoni, Hepi (2012). WAJAH POLITIK MUAWIYAH BIN ABU SUFYAN: MENGURAI SEJARAH KONFLIK SUNNI-SYIAH (Original ed.). Pustaka Bustan. p. 29. ISBN 978-9791324076. Retrieved 7 February 2020.

- Sayyid, Kamali. "رجل بألف رجل". maktubes. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Sallabi, Ali Muhammad (2007). Muawiyah bin Abi Sufyan (original ed.). مكتبة العصيرية. p. 654. ISBN 978-9953347172. Retrieved 3 February 2020.

- Indra, Gunawan (2014-03-13). Legenda 4 Umara Besar. Elex Media Komputindo. p. 280. ISBN 978-6020234779.

- Rex, Smith (2015). History of al-Tabari Vol. 14, The: The Conquest of Iran A.D. 641-643/A.H. 21-23. p. 164. ISBN 978-1438420394.

- Humphrey, R. Stephen; Muhammad Tabari (January 1990). Humphrey, Stephen (ed.). The History of al-Tabari Vol. 15: The Crisis of the Early Caliphate: The Reign of 'Uthman A.D. 644-656/A.H. 24-35. SUNY press. p. 285. ISBN 9780791401545.

- Al Ghazali (2015). Muawiyah - Sebuah Biografi Awal. PTS Publications & Distributors Sdn Bhd. p. 176. ISBN 978-9674114466. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Lynch 2016, p. 539.

- Bashir-ud-Din Mahmud Ahmad, Mirza (June 1, 2013). The Outset of Dissension in Islam. Islam International Publications Ltd. p. 167. ISBN 978-1848800922. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Gil, Moshe (27 February 1997). A History of Palestine, 634-1099. Cambridge University Press. p. 135. ISBN 0521599849. Retrieved 26 January 2020.

- Abbah, Ibrahim Abu (1997). Hak dan Batil dalam pertentangan (in Indonesian). Gema Insani. ISBN 9789795614449.

- Saʻd, Muḥammad Ibn (1997). The Men of Madina. Ta-Ha Publishers. ISBN 9781897940686.

- Abu Abbah, Ibrahim (1997). Hak dan Batil dalam pertentangan. Gema Insani, 2017. ISBN 9789795614449. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- Sahih Muslim (29) al-Iman [49]

- al-Asqalani, Ibn Hajar. "Siyar a'lam Nubala/'Ubadah bin al-Samit". Wikisource. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- al Quraibi, Professor Ibrahim; Askar Lc., Dahya (2016). Tarikh Khulafa. Qisthi press. p. 630. ISBN 978-9791303408.

- الشيمي, علي شفيق (14 July 2019). ""بقيع مصر الثاني".. "بهنسا" مدينة الشهداء". Ahram. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Ahmad Ghadanfar, Mahmud (2001). "The Commanders of Muslim Army". Google book. Darussalam publisher. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Sebag Montefiore, Simon (Jan 2, 2012). Jerusalem: The Biography. Pustaka Alvabet. p. 226. ISBN 978-6029193022. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Salama, Yusuf. "عبادة بن الصامت أول قاض ٍبالإسلام في بيت المقدس". Al itihad. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Yusuf, Ghazwan. "Al-Bazaar mosque... 'Ubadah bin Samit lay it first foundation". 02 April 2009 Esyria. Retrieved 28 January 2020.

- Ajeng Tedjomukti, Ratna. "Masjid Amru Bin Ash Tempat Sujud Pertama di Afrika; 07 Okt 2019". Khazanah Republika. Republika press. Retrieved 27 January 2020.

- Ibn Hisham, Abu Muhammad (October 2019). Sirah Nabawiyah-Ibnu Hisyam. Qisthi press. p. 792. Retrieved 31 January 2020.

- "عبادة بن الصامت". Islam Story. Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- "Twelve Ranks of the Companions". Archived from the original on 2011-04-23.

- Abdul Jabbar, Suhaib. "Sunnah and Musnad ibn Hanbal". Retrieved 30 January 2020.

- Lynch, Ryan J. (July–September 2016). "Cyprus and Its Legal and Historiographical Significance in Early Islamic History". Journal of the American Oriental Society. 136 (3): 535–550. doi:10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0535. JSTOR 10.7817/jameroriesoci.136.3.0535.