Zashiki-warashi

Zashiki-warashi (Japanese: 座敷童子 or 座敷童, "guestroom child"), sometimes also called Zashiki Bokko (Japanese: 座敷ぼっこ, "guestroom basker"), are spirit-like beings told about mostly in the Iwate Prefecture.[1] They are said to be gods that live in zashiki storage rooms,[2] and they would perform pranks, and those that see one would be visited with good fortune. There are also legends of how they would bring fortune to families. They are also known from Kunio Yanagita's Tōno Monogatari, Ishigami Mondō, and stories about them appear in the 17th and 18th chapters of the Tōno Monogatari and the 87th chapter titled "Zashiki-warashi" of the Tōno Monogatari Shūi, and in this 17th chapter it is written "families with whom this god dwells are freely able to prosper at will" (kono kami no yadoritamafu ihe ha fūki jizai nari to ifu koto nari) and "zashiki-warashi are also called 座敷童衆". In recent years, they are also known from television programs and magazines that reported about various Iwate Prefecture ryokan where it is said to be possible to see a zashiki-warashi such as the Ryokufūsō, the Sugawara Bekkan, and the Warabe.

It is similar to the Russian folk story of the Domovoi.

Concept

Reports have mostly been in the Iwate Prefecture, but there are also some scattered across the Aomori Prefecture, the Miyagi Prefecture, the Akita Prefecture, and others in the Tōhoku region.

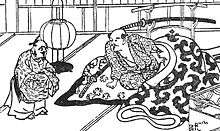

Generally they have a red face, hair that hangs down, and have the appearance of that of a child about 5 or 6 in age, but this age is also said to vary depending on the house that they settle in, with examples ranging from a minimum of around 3 years in age and a maximum of around 15 years in age.[3] They have a Bob cut hair or very short cropped hair. Both male and females ones have been seen, and the male ones are said to wear blackish clothes with a kasuri or striped pattern, and the females ones are said to wear a red chanchanko, kosode, and sometimes a furisode.[3] It is also said that there are some whose appearance is unclear, making their gender unknown.[3] Sometimes multiple would settle in a house at once, like a boy and a girl. There are also some legends that tell ones that look like a black beast, as well as ones that look like a warrior.[3]

They like causing mischief, so they are said to leave ash or bleaching powder on top of little footprints and at night time, they are said to make sounds like that of a revolving spinning wheel, and they would also make sounds in an inner room making sounds like that of a kagura performance. There are also tales told about how when someone in the family is sewing alone, there would be sounds similar to the rustling of papers or someone snorting, etc., and when the wooden door is opened there would be no one there. It is also said that at night, they would do pranks such as riding on top of guest room futons and turning over the pillows in order to not let the person sleep, and when attempts are made to stop it, it would be too strong and powerful for anyone to even affect its actions.[2] Sometimes they also play with children.[2]

In Iwate, there are legends of how the zashiki-warashi of a shrine at Hayachine would follow a shrine visitor who came from afar and follow them into different lands. There is also legends of how the zashiki-warashi would teach the nursery rhyme of Iwate to the children of those lands.[4]

In Gonohe, Aomori Prefecture, there is a legend of how when a new house is built, a zashiki-warashi can be called into it by burying a golden ball under the floors.[5]

There are also theories about how they cannot be seen by anyone other than members of the family or how they can only be seen by children but not adults. There are stories about how when adults counted children, there would be 1 more person than there was originally, but as adults do not understand what zashiki-warashi are, they would not know who is the extra person. Stories like these also frequently appear as themes in literature.[6]

Relation to family prosperity

An example of a very characteristic folk belief about how families with a zashiki-warashi would prosper and families whose zashiki-warashi have gone away would decline. This aspect shows that zashiki-warashi are like gods of fortune or protective spirits that rule over a family's prosperity and decline.[6][7]

In the Tōno Monogatari, there are tales such as one telling about how a family was wiped out by foodborne illness after its zashiki-warashi left it and another tale about how in the Iide section of the village of Tsuchibuchi, Iwate Prefecture (now part of the city of Tōno), a wealthy family's zashiki-warashi was shot by a kid with a bow and arrow causing it to leave the family and since then the family's fortunes declined.[8] There is also the view that the way families would decline after a zashiki-warashi leaves it and the way families would prosper after a binbōgami leaves it are related.[9]

There is the theory that a white zashiki-warashi is a sign of good things to come and the sight of a red one (with a red face, red clothes, and a red bucket in its hands) is a sign that a zashiki-warashi would leave the family leading to bad things to come. There are also examples where a family that saw a red-clothed one all died from foodborne illness.[10]

Customs

Zashiki-warashi are there in inner guestrooms (zashiki), and their existence is said to have an effect on the direction the family goes in, so there are some families that treat them hospitably and offer them meals every day. They are said to like azuki meshi, so there are families that offer some azuki meshi every day, and if it is not eaten, it is said to be an omen for the family's decline.[6] Zashiki-warashi generally work the same way as having kitsune or having inugami, but the difference between them and zashiki-warashi is that for a zashiki-warashi to live there is never considered a nuisance, and in fact they are even protected as gods, and a family that has a zashiki-warashi is usually treated by other people around with respect.

In the area around the city of Ninohe, there is a custom of making up a room with desserts and toys left inside for a child who had died or were killed as infants (infanticide), and giving worship to this child, a custom that remains to the present day, and there is also a custom of making a room that a child would like in order to make a zashiki-warashi stay at the house in order to bring the family to prosperity.[10]

According to the Tonō Monogatari, the house of a certain wealthy family in the town of Tsuchibuchi had a small space that was called the "Zatō room", and it is considered to be the room that would be used to await the Zatō (a kind of member of the build persons' guild such as the tōdōza or a ranking of members of related groups such as the Anma, moxibustion practitions, and members of the biwa hōshi, among other organizations) every time a banquet was called in the past,[11] but the literary researcher Sukeyuki Miura surmises that perhaps this room was used to give worship to the god's protective spirit.[9]

Kinds

Zashiki-warashi have various regional names such as zashiki-warabe (座敷童), zashiki-warashi (座敷童衆), zashiki-bokko (座敷ぼっこ), okura-bokko (御蔵ボッコ), zashiki-kozō (座敷小僧), and karako-warashi. The name "zashiki-bokko" is used in the inland regions of Iwate, and this name was also used in the writings of Kenji Miyazawa.[3]

There are also regions and legends where zashiki-warashi have rankings, and in the Jippōan Yūreki Zakki (十方庵遊歴雑記), there can be statements seen about zashiki-warashi in the area of Inase, Esashi, Iwate Prefecture (now Esashi District, Ōshū, and according to this, zashiki-warashi that are in a home's dirt floor room are called kometsuki-warashi, notabariko, usutsuriko, among other names, and the white, most beautiful zashiki-warashi that is in the inner zashiki is called the chōpirako.[12] Among these, there are some that have no influence on the family's fortunes and instead merely move around the house making noises, and there are not merely a few that have been deemed creepy.[3]

There are also some that have arms that are long and thin like vines, which they use to beckon people as well as warn of disasters like floods and tsunami, and these can be called hosode (細手, "thin arms") or hosode nagate (細手長手, "thin arms long arms").[12] There is also a similar story telling of how "a poor man once threw firewood into the water, was invited into the dragon palace, and received as a gift an ugly-looking but fortune-bringing ryūkyū-warashi (dragon palace child)". There are also zashiki-warashi that stay in the dozō, and they are called kura-warashi or kura-bokko (child of the storehouse).

According to the essay "Zashiki-warashi no Hanashi" (ザシキワラシの話, "Stories about Zashiki-warashi") by the folklorist Kizen Sasaki, in a certain home in the aforementioned village of Tsuchibuchi, there is a kabukire-warashi (tree stump child) that lives in the "Mada no Ki" (meaning "Bodhi tree") that is said to take on the appearance of a child and sneak into the family's zashiki to perform pranks on the family's daughter, as well as take on an appearance with a red face and play on walnut trees where the tree splits into three.[13] It has also been interpreted to be a spirit of this Mada no Ki.[14]

Despite there being many legends of the zashiki-warashi in the Tōhoku region, there are not so many only in Akita Prefecture. This is said to be because Akita has the sankichi oni, so lower-class yōkai would not enter Akita.[6]

Origins

As mentioned previously, Kizen Sasaki noted that perhaps they are the spirits of children who were crushed to death and buried at the home.[15] In the Tōhoku region, infanticide was called usugoro (臼殺, or "mortar kill"), and it is said that children who were killed this way to reduce the number of mouths to feed would be killed by being crushed by a stone mortar and there was a custom of buring them not with a grave, but in the dirt floor room (doma) or in the kitchen, and it is said that the spirits of such children would on rainy days walk around outer edges shaking frighting the guests, which is said to be seen to resemble deeds similar to that of a zashiki-warashi.[10] The aforemtioned notabariko and usu-tsuki warashi are seen to be lower ranking among the zashiki-warashi, and the former would peek out from the inner dirt floor (doma) room and crawl around while the latter would use a mortar to make a sound, and due to creepy acts such as this,[12] it is sometimes suggested that these kinds of zashiki-warashi have a relation to the fact that that the location where the infantide happened is in the dirt floor (doma) room or underneath a mortar.[3]

In addition to this relation to infanticide, the fact that the zashiki-warashi are in old homes as well as the fact that they are often told in relation to legends about how after a visiting Buddhist pilgrim from outside the village was killed, the family of the home came to ruin, so it has been suggested that these zashiki-warashi are signs of the dark undersides of the village's community.[9]

In the "Zashiki-warashi wo Mita Hitobito" (座敷わらしを見た人びと, "The People Who Saw Zashiki-Warashi") by the author Sadako Takahashi, there are also stories about zashiki-warashi that came about as a curse that resulted from carpenters and tatami makers that weren't able to do their construction jobs in comfort, and it is said that there were rituals of taking a doll that had a bit of its wood peeled off and inserting them in between the pillars and beams.[3]

There are also many theories that their true identity is that of a kappa, and there are stories of zashiki-warashi being a kappa that lived in the depths who would rise up and go into a nearby home to do pranks, as well as stories of zashiki-warashi that were kappa that have settled into a home.[16]

Concerning why zashiki-warashi look like children, seeing how in Buddhism there are gōhō-warashi (wrathful gods that protect Buddhism and take on the appearance of a child) have the appearance of a child, there is the theory that they come from folk beliefs in how children connected gods and humans,[7][17] as well as the theory that the appearance of a child embodies divinity.[9]

In Kunio Yanagita's view, just like the gōhō-warashi that were called forth from the heavens by high priests, the protective spirits of Buddhism and folk mikos are related to the faith in giving respect to the freshness of the spirits of young leaves, and this is related to the faith in the zashiki-warashi who became protective spirits of a home in order to convey the will of divinity to humans. In folkloristics after Yanagita as well, there has been debate on subjects such as the relation to Okunai-sama and the relation of children that come from another realm such as the Ryūgyū-warashi (dragon palace warashi), among other topics.[9]

Also, the folklorist Kazuhiko Komatsu views warashi (children) from the point of view of cultural anthropology, and taking on the question of the fortune of homes and the movement of wealth within a village, he notes that zashiki-warashi share in almost all their characteristics with animal spirit possession such as izuna-tsukai ("weasel-using"), and from an analysis of the supremacy and inferiority within the community of families with a spirit haunting them, he notes that zashiki-warashi have been used as a basis for explaining changes in fortunes within folk society, especially for old homes and families.[9]

In Ueda Akinari's late Edo-period yomihon the Ugetsu Monogatari, in the story "Hinpuku-ron" (Theory of Wealth and Poverty), in Mutsu Province (now Aomori Prefecture), in a certain home of a warrior family, a spirit of money appears in the form of an old man going by the name of "Ōgon no Seirei" (meanin "golden spirit") who said "I'm glad you treat money as something important to you, so I came to tell a story", but the doctor of letters Masamichi Abe gives the thought that perhaps this is an older, more prototypical type of zashiki-warashi.[18]

Legends after the war

To the people of Tōhoku, the zashiki-warashi was certainly not a legend that came around after the war, and tales of zashiki-warashi were told even in the times of Meiji, Shōwa, and beyond. According to Kunio Yanagita's Yōkai Dangi (妖怪談義), it is said that in the year 1910 or Meiji 43 around the time of July, in the village of Tsuchibuchi (now Tōno, Iwate Prefecture) in Kamihei District, Rikuchū, a zashiki-warashi appeared at a school that was visible only to the first year students but not to the older students and adults.[19]

Certain ryokan that have continued to be managed in the Shōwa and Heisei periods and beyond such as the Ryokufūsō at the Kindaichi Onsen in Iwate Prefecture, the Sugawara Bekkan, and the Warabe both in Tenjin village in Morioka Prefecture are known to be lodges where a zashiki-warashi dwells, and there have been tales of guests who saw zashiki-warashi, heard footsteps, were physically touched.[3] However, unlike in the usual legends of zashiki-warashi, the one at Ryokufūsō is considered to be an ancestor that died from an illness and became a protective spirit.

Close to the Warabe, there is a Hayachine Shrine that was opened more than 1200 years ago, and it is said that since festivals for making prayers towards zashiki-warashi have been done ever since the establishment of the Warabe, the shrine's zashiki-warashi goes to the Warabe.[3]

The zashiki-warashi of the Sugawara Bekkan was originally a god of fire of the Edo period that protected the proprietress's original home from fire,[20] and it is said to have followed this proprietress when she married into the family of this establishment. There have also been tales about how guests to this ryokan have been successful in their marriage and jobs.[21]

Similar tales across Japan

Similar to the zashiki-warashi are the zashiki-bōzu of Kadotani, Tōtōmi Province (now Shizuka Prefecture) and the akashaguma of Tokushima. Near one of the inner temples of the Kotohira-gū in Shikoku, it is said that at night time an "akashaguma" appears from a butsudan. "Akashaguma" refers to the fur of a bear that has been stained red, and it is said that a little childlike being wearing this would tickle the old woman owner of this house every night.

In the former Higashiyatsuhiro District in Yamanashi Prefecture, it is said that there is an okura-bōzu (お倉坊主, "warehouse bonze") that stays within the warehouse, and this is thought to be a type of zashiki-warashi.[22][23]

In Ishikawa Prefecture, there is the makuragaeshi and it is said that if one sleeps in the zashiki of a certain house, especially if one wields two swords, has hair that stands up, wears western clothing, and puts on a haughty face, then one would get dragged into a neighboring room.

The zashiki-warashi of Shirotori, Ōkawa District, Kagawa Prefecture (now part of Higashikawa), is told to appear as a little girl who is called oshobo due to the small, slight (shobo-shobo in Japanese) way it hangs, and sometimes it is said to be invisible to the members of the house,[3] while other times it is said to be visible only to the members of this house.[6]

In addition, in Hokkaido there is the ainukaisei said to attack people in their homes while they sleep, and in the Okinawa Prefecture there is a yōkai called the akagantaa said to play pranks on people in their homes while they sleep, and sometimes these are interpreted to be the same kind of beings as zashiki-warashi.[6][12]

The folklorist Shinobu Orikuchi enumerates examples such as the okunai-sama, the zashiki-bōzu, the akashaguma, the kijimuna of Okinawa, gaataro of Iki, etc., and sees in them examples of tales of a faithful spirit that came from another land to do work for a certain family whose disappearance would result in the decline of the family. He notes how zashiki-warashi do not descend into the garden and suggests that this is related to how performing arts in the past had a division between "garden", "zashiki", and "stage".[2]

Etymology

The name breaks down to zashiki (Japanese: 座敷), a sitting room or parlor, usually with tatami flooring, and warashi (Japanese: 童子), an archaic term for a child, used particularly in the northeast of Japan.[24][25]

Description

The appearance of this spirit is that of a 5 or 6 year child with bobbed hair and a red face.[26] Zashiki-warashi can be found in well-maintained and preferably large old houses.[27] It is said that once a zashiki warashi inhabits a house, it brings the residence great fortune; on the other hand, should a zashiki-warashi depart, the domain soon falls into a steep decline.[28]

As the zashiki warashi is child-like in nature, it is prone to playing harmless pranks and occasionally causing mischief. They are known for running around and making noise, even adjusting the bedding of overnight guests.[29] Sometimes they leave little footsteps in ashes. There are different variations as to who can see the zashiki-warashi; usually this is limited to inhabitants of the house, sometimes to children.[30]

Yōkai similar to zashiki-warashi in other parts of Japan include: the makuragaeshi in Ishikawa Prefecture – another creature which alters bedding;[31] the ainukaisei in Hokkaido; and the akagantā found in Okinawa.[32]

The Ryokufūsō in Kindaichi Onsen, which burned down on October 4, 2009, was famed for its zashiki warashi.[33]

Sightings

By the end of November 2015, Mirror website offered video footage from a home video camera in Japan. That can capture the thing of what looks like a girl wearing a kimono walking in the house. But her body is translucent and can walk through the wall. Believe that she is zashiki-warashi.[34]

In popular culture

- In the animated series Mononoke, zashiki-warashi were represented by the spirits of fetus that were aborted by the prostitutes in a brothel.[35]

- In the animated series Centaur No Nayami, zashiki-warashi was represented by a small child that played with Sue Mitama, the younger sister of Manami Mitama.

Notes

- ↑ Takayuki 1996, pp. 173–174.

- 1 2 3 4 渡辺他 1987, p. 121

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 村上他 2008, pp. 7–12

- ↑ 怪談レストラン編集委員会・松谷みよ子責任編集, ed. (2007). 座敷わらしレストラン. 怪談レストラン. 童心社. pp. 17–25. ISBN 978-4-494-01373-9.

- ↑ 多田 1990, p. 275.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 多田 1990, pp. 256–261

- 1 2 真野他 1980, pp. 134–135

- ↑ 柳田 1910, pp. 23-25.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 三浦他 1992, pp. 256–257

- 1 2 3 杉山他 2008, pp. 100–103

- ↑ 柳田 1910, pp. 48–52

- 1 2 3 4 佐々木 1973, pp. 15–55

- ↑ 佐々木喜善 (1924). "ザシキワラシの話". 郷土趣味. 5巻 (2号(通巻50号)): 6. NCID AN00373399. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ 多田 1990, p. 229.

- ↑ 図説 地図とあらすじで読む 日本の妖怪伝説. 志村有弘監修. 青春出版社. 2008. p. 71. ISBN 978-4-413-00965-2.

- ↑ 佐々木 1973, pp. 65–67.

- ↑ 日本の妖怪百科. 4. 岩井宏實監修. 河出書房新社. 2000. p. 30. ISBN 978-4-309-61384-0.

- ↑ 阿部正路 (1981). 日本の妖怪たち. 東京書籍. pp. 117–120. ISBN 978-4-487-72164-1.

- ↑ 柳田國男 (1977) [1956]. 妖怪談義. 講談社学術文庫. 講談社. p. 123. ISBN 978-4-06-158135-7.

- ↑ 安部晃司他 (2006). 日本の謎と不思議大全. ものしりミニシリーズ. 東日本編. 人文社. p. 40. ISBN 978-4-7959-1986-0.

- ↑ ペリー荻野. "ちょんまげ道中 座敷わらしがくれる福をキャッチする心". 読売新聞. 2009年7月5日付日曜版. p. 3.

- ↑ 郷田洋文. "家の神の水神的性格". 西郊民俗 (9): 6. NCID AN00086422. Retrieved 2014-09-23.

- ↑ 村上健司編著 (2000). 妖怪事典. 毎日新聞社. p. 74. ISBN 978-4-620-31428-0.

- ↑ Matsumura 2006.

- ↑ Yoshimura 2015, p. 170.

- ↑ Blacker 1963, p. 87.

- ↑ Takayuki 1996, p. 173.

- ↑ Yoda & Alt 2013, pp. 31–32.

- ↑ Yoshimura 2015, p. 149.

- ↑ Nomura 1987, p. 121.

- ↑ Foster & Kijin 2015, pp. 236–239.

- ↑ Foster & Kijin 2015, p. 239.

- ↑ Tsuruta & Fujiyoshi 2016, p. "Zashiki-Warashi Inn" Rebuilt 6 Years and 7 Months after Fire.

- ↑ "ขนหัวลุก ! คลิปผีเด็กหญิงโผล่กลางห้อง เจ้าของบ้านเชื่อเป็นภูตินำโชค". Kapook.com (in Thai). 2015-12-02. Retrieved 2018-07-22.

- ↑ Nakamura 2007.

References

- 佐々木喜善 (2007) [1973]. 遠野のザシキワラシとオシラサマ. 中公文庫. 中央公論新社. ISBN 978-4-12-204892-8.

- 杉山茂勲他 (2008). 早川和樹編, ed. こわい話 - あなたの知らないニッポンの"恐怖". ミリオン出版. ISBN 978-4-8130-2076-9.

- 多田克己 (1990). 幻想世界の住人たち. Truth In Fantasy. IV. 新紀元社. ISBN 978-4-915146-44-2.

- 真野俊和他 (1980). 桜井徳太郎編, ed. 民間信仰辞典. 東京堂出版. ISBN 978-4-490-10137-9.

- 三浦佑之他 (1992). 吉成勇編, ed. 日本「神話・伝説」総覧. 歴史読本特別増刊・事典シリーズ. 新人物往来社. NCID BN08606455.

- 村上健司・高橋貞子他 (2008). 講談社コミッククリエイト編, ed. DISCOVER妖怪 日本妖怪大百科. KODANSHA Officisil File Magazine. VOL.05. 講談社. ISBN 978-4-06-370035-0.

- 柳田國男 (1976) [1910]. 遠野物語・山の人生. 岩波文庫. 岩波書店. ISBN 978-4-00-331381-7.

- 渡辺公一他 (1987). 野村純一他編, ed. 昔話・伝説小事典. みずうみ書房. ISBN 978-4-8380-3108-5.

- Blacker, Carmen (1963). "The Divine Boy in Japanese Buddhism". Asian Folklore Studies. 22: 77–88. doi:10.2307/1177563. JSTOR 1177563.

- Foster, Michael Dylan; Kijin, Shinonome (2015). The Book of Yōkai: Mysterious Creatures of Japanese Folklore. University of California Press. ISBN 978-0-520-27102-9.

- Hamashita, Masahiro (August 2005). "Forests as Seen by Yanagita Kunio: His Contribution to a Contemporary Ecological Idea". Diogenes. 52 (3): 13–16. doi:10.1177/0392192105055166. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Komatsu, Kazuhiko (August–October 1987). "The Dragon Palace Child: An Anthropological and Sociohistorical Approach". Current Anthropology. 28 (4): S31–S39. doi:10.1086/203576. JSTOR 2743426.

- Matsumura, Akira (2006). Daijirin (3rd ed.). Sanseido Books. ISBN 978-4385139050.

- Nakamura, Kenji (July 2007). "Zashiki-Warashi". Mononoke. Fuji TV.

- Takayuki, Tatsumi (December 1996). "Deep North Gothic: a Comparative cultural reading of Hearn, Yanagita and Akutagawa". The Geibun-Kenkyu: Journal of Arts and Letters. 71: 160–183. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Tsuruta, Yusuke; Fujiyoshi, Kyoko (5 May 2016). ""Zashiki-Warashi Inn" Rebuilt 6 Years and 7 Months after Fire". Yomiuri Shinbun Online. Retrieved 16 May 2016.

- Nomura, Junichi (1987). Pocket Encyclopedia of Folktales and Legends. Tokyo: Mizuumi Shobo. ISBN 9784838031085.

- Yoda, Hiroko; Alt, Matt (2013). Yokai Attack! The Japanese Monster Survival Guide. Tuttle Publishing. ISBN 9781462908837.

- Yoshimura, Ayako (2015). "To Believe and Not to Believe: A Native Ethnography of Kanashibari in Japan". Journal of American Folklore. 128: 146–178. doi:10.1353/jaf.2015.0023 (inactive 2018-09-05). Retrieved 16 May 2016.

External links

- On Zashiki-Warashi | 百物語怪談会 Hyakumonogatari Kaidankai, by Mizuki Shigeru at hyakumonogatari.com

- The Last of the Zashiki warashi, Awa Life, March 2002

- The Story of Zashiki warashi no geta, Nanbu Kiri Geta Preservation Society

- The Ryokufūsō HOTEL Japan

- Zashiki-warashi: Spooky Japan - Folk Legends - Kids Web Japan - Web Japan

- 133 Yokai Statues on Mizuki Shigeru Road; scroll down to see 67. Zashiki Warashi (Chamber child)