Women in firefighting

.jpg)

Firefighting was a predominantly male profession throughout the world. Since the 1970s, women have made inroads in both professional and volunteer fire departments in multiple countries. In modern times, women have served in a variety of fire service roles including as fire chiefs. Nonetheless, they make up less than 10% of firefighters even in the countries where they are best represented.

History

Many ancient civilizations had a form of organized firefighting. One of the earliest recorded fire services was in Ancient Rome. The Aboriginal Australians had been managing and responding to wildfires for thousands of years, with women being involved.[1]

Firefighting became more organized from the 18th century onwards, led with the rise of insurance companies and then with the rise of government fire services in the 19th century. In 1818, Molly Williams was recorded as being the first female firefighter in the United States. As a slave in New York City, she joined a volunteer engine company.[2] Young women in boarding houses in the United Kingdom were taught fire drills, including high ladder rescues. During World War II, women served in the wartime fire services of the United Kingdom, Australia and New Zealand, though mostly in administrative and support roles.

As a result of the second-wave feminism movement and equal employment opportunity legislation, official obstacles to women were removed from the 1970s onwards. The first female firefighter in the United Kingdom was recruited in 1976,[3] while the first in New Zealand joined in 1981.[4] Many fire departments required recruits to pass tough fitness tests, which became an unofficial barrier to women joining. This led to court cases in a number of countries. In 1982, Brenda Berkman won a lawsuit against the New York City Fire Department over its restrictive fitness test. She and 40 others then joined as its first female firefighters. A similar lawsuit led to the Supreme Court of Canada ruling in 1999 that fire departments could not use restrictive fitness tests unless they could justify the need for them.[5][6]

Nevertheless, the percentage of women recruited by fire departments has been low. In the UK, women make up 5% of firefighters[7] which is less than the percentage for police officers (29%),[8] paramedics (38%)[9] and military personnel (10%).[10] A report by the London Fire Brigade found that discouraging factors included the portrayal of firefighting in the media, a lack of information available to young girls and unrealistic ideas about the role.[11] Other issues include shift patterns that are not suitable for mothers with young children.[12]

By country

Australia

First Nations peoples - women and men of different language, tribal or nation groups[13]- used, managed and responded to fires across Australia for 60,000 years before invasion, colonisation and the involvement of white women in firefighting.[1][14]

Amazon Ladies Fire Brigade, Armidale NSW 1901-1905

The first all-female non-Indigenous crew was recruited in 1901 in Armidale, NSW Australia. Known as 'The Amazons' [15] this volunteer crew complimented the all-male paid firefighting crew, and was the first example in Australia of male and female crews doing routine fire drills together using the same equipment. Station Officer Minnie Webb was the first female Captain in Australia.[16] The creation of the Amazon Ladies Fire Brigade and their operational and dress uniforms was inspired by Captain Webb of the paid firefighting brigade in Armidale. Captain J.T.A. Webb became captain in 1898. He held this position until his death on 17 May 1924. It was he who formed the first women's fire brigade in the early 1900s and also instructed the girl's brigade at the New England Girls School and the fire squad at The Armidale School, October 1923.[17] (Penrith Fire Museum [18] has a 'behind the scenes' archival collection pertaining to Captain Webb in relationship to the paid fire brigade). Webb immigrated from England, and he brought with him a vision of trained female fire responders that were common on all-female boarding houses in Britain (see United Kingdom, below on this page). It was formed after the fire in 'Cunningham House' Armidale NSW Australia [19] The Amazons was a 'one-off' local initiative and the Webb children were recruited into both the male and female brigades. The model was not adopted elsewhere in Australia. However, the Dubbo Dispatch and Independent Bulletin of 1905 reported[20] that the Dubbo Bridages had attended in Dubbo with 'upwards of 70 Brigades' from across NSW, and an 'exhibition of hose and ladder...and life-saving' had been performed by the Amazon Ladies Brigade [21][22][23]

Unlike Britain, Australian jurisdictions did not establish voluntary female brigades during WWI, and despite incredible interest in the Amazons during 1901-1905, no other jurisdictions took up the idea. Captain Minnie Webb went on to become a nurse serving in WWI.

Women's Fire Auxiliaries, World War II

As was the case in Britain, women's fire auxiliaries were established in World War II in most jurisdictions in Australia (history is yet to be written, but see[24] for a snapshot) because many male career firefighters enlisted. Tasmania was ordering uniforms for the Women's Fire Auxiliary in January 1940.[25] On 20th August 1941 The Tasmania Women's Fire Auxiliary were part of a parade (a 'march-past') for UK Prime Minister Winston Churchill.[26] Queensland established a Women's Fire Auxiliary in October 1941.[27] Their duties were to include 'driving and trailing vehicles to fires, repairing hoses, operating chemical extinguishers, looking after canteens, and extinguishing incendiary bombs'. The Forestry Department of Western Australia recruited an all-female fire crew at a place called Sawyers Valley. Initially only employed on weekends they soon proved their worth and became full-time. In addition to fire suppression they carried out fuel reduction burning, firebreak maintenance, fire spotting and upgrading bush phone lines.[28] In 1942 the WA Fire Auxiliary, made of up men and women, gave a demonstration of their skills.[29] In the same year (1942) the Board of Fire Commissioners of NSW established the Women's Fire Auxiliary.[30] Women served as volunteer firefighters in urban and rural locations across Australia and New Zealand. New South Wales recruitment strategy included Wagga Wagga[31] and Newcastle,[32][33][34] Wollongong[35] and Broken Hill.[36] A uniform, including a helmet, dress uniform hat, operational overalls and dress uniform jacket was provided. The Australian War Memorial has photos of the NSWFB uniform.[37] Dorothy Barrett, organiser and Chief of the NSW Women's Fire Auxiliary was photographed in 1946 in uniform[38] (A history of the female Chiefs of the Women's Fire Auxiliaries has not been written. However Trove has established a 1947 Press Cuttings book[39]). Also in 1942 South Australia established a Women's Fire Auxiliary and recognition was given to the vital role women were to play in emergency response[40]

(At the 2006 Women in Fire Fighting Conference, Childs curated a reproduction of historic uniforms[41])[42]

The post-war era saw the growth of many local women's auxiliaries across Australia (history yet to be written). In the 21st century these women would be seen as providing operational support and contributing to community fire safety, but in the post-war era a gendered appreciation of the roles of women applied and they were often portrayed and respected as tea ladies and sandwich makers. In fact the women who volunteered made an important contribution to fire preparedness and response at a time when laws had been passed to ban women from applying to become paid firefighters. See for example,[43][44][45]

It is thought that Heather Barnes, Denise Butcher, Dawn Maynard and Allison Meenahan of the NSW Fire Brigades were the first paid career firefighters in Australia recruited in 1985.

Notable moments

1901 The Amazons was formed in Armidale NSW Australia

1941-1945 Women's Fire Auxiliaries were established across Australian jurisdictions

1945-1947 Pre-war bans on single and married women being employed in certain industries[46][47] including firefighting, were reinstated as part of demobilisation

1950-70s Many Women's Fire Auxiliaries were formed, such as the Morphett Vale and Districts EFS Ladies Auxiliary; and Burnside CFA SA Women who took a more active role learning basic firemanship (sic) and the operation of the radio room

1977 NSW Anti-Discrimination law passed

1984 The Australian Sex Discrimination Act was passed[48]

1985 Heather Barnes, Denise Butcher, Dawn Maynard and Allison Meenahan became the first female firefighters in the NSWFB

1987 Adrienne Clarke became South Australia's first female professional firefighter with the Metropolitan Fire Service (SAMFS)

1988 The induction of the first professional female firefighters in the MFB took place in September (Names of women?)

1992 Melanie Goehr first professional female firefighter in NTFRS

1994 Kristen Appel appointed leader of an all-female firefighting team of NT Park Rangers in charge of Arltunga Historical Reserve East Macdonnell Ranges NT

1998 Vicki Hunter, Sally Foote and Dawn Maynard first female Station Officers in NSWFB

1999 Shameena Wells became the first Muslim woman in Australia to win first place at the NSWFB field day held at the NSW Fire Museum Penrith NSW

2000 5 female firefighters of the NSW National Parks and Wildlife Service awarded a national Firefighting medal (names of women?)

2001 The first all-female and all-First Nations fire crew was established at Lake Tyers, Victoria

2002 The first female Aviation Rescue and Firefighting graduates were deployed by Air Services Australia (names of 2 women?)

2004 Jennifer Filmer awarded a Medal of the Order of Australia for 30 years service to rural fire in Victoria

2004 Viviene Raffaele was awarded the Australasian Fire Service Medal for services to firefighting in the ACT

2005 First Women in Firefighting Forum (WIFF)

2005 The WA Branch of the United FireFighters Union replaced the word 'firemen' with 'firefighter' on their website

2006 First Australasian Women in Firefighting Conference

2008 Michelle Young was appointed as the first female Station Officer with Queensland Fire & Rescue

2014 Charmaine Sellings, Rhonda Thorpe and Katrina Mullet, long time members of the all-female and all-First Nations firefighters of the Lake Tyers Brigades of the CFA Victoria, were awarded 10 year service medals

2016 Women made up 50% of the recruits graduating class of Fire and Rescue NSW (formerly NSWFB)[49]

The women and firefighting agenda

The first National Women in FireFighting Forum (thereafter known as WIFF) with the theme 'Firing Up Women' took place at the Holiday Inn, Sydney Airport, Mascot, Friday 13 May 2005. It was opened with a keynote address by the Sex Discrimination Commissioner Pru Gow.[50] A second conference was held in 2006[51] and included New Zealand female firefighters. The theme was 'Same but Different'. The first timeline of women in firefighting was created.[52] A vote was unanimously recorded to establish a women in firefighting association run by and for female firefighters, and out of this vote Women and Firefighting Australasia (WAFA) was born. In 2007 the first Board of WAFA was established and included President- Susan Courtney, Secretary- Cathryn Dorahy, Treasurer- Cathryn Dorahy, Board Members- Barbara Lewis, April Winkle, Caroline Ortel, Valerie Ingham.

In 2006 Childs[53] reported that less than 5% of any fire service in Australia was made up of full-time paid female firefighters, and also reported a web survey under the title 'Not just fitting in'.[54] Ainsworth et al (2013) argued that in 2006 indicated that out of 33,659 volunteer firefighters, 3,798 (11%) were women. In 2011, this number had increased to 5,466 (14%).[55] In 2015 the Women in Firefighting Australasia report 'Gender Balance Overview Australasian Firefighters 2015'[56] indicated that no fire agency had succeeded in improving the overall percentage about 5%. However, while overall total percentages had not been exceeded between 2006 and 2015, overall percentages across all fire services had improved. For example, the Northern Territory had improved from 0% to 2%.

The Fire and Emergency Male Champions of Change was established in April 2017.[57]

Women and Firefighting Australasia (WAFA) hosted a series of conferences once incorporated.[58] In 2010 the theme of the Conference was 'Resurgence - Becoming Stronger'. In 2014 the theme of the conference was 'Women at the fire front: innovation, motivation & inspiration'. In 2016 the theme of the conference was 'Stepping Up and Standing Out', and in 2018 it was 'Looking forward, looking back; Shaping the New Norm'. In 2018 WAFA commenced the #WAFAWednesday and #trailblazerThursday twitter campaigns, and joined the ‘100 Days for Change’ campaign by launching an ‘online mentoring program to boost opportunities for their members’ #100daysforchange.

Prior to 2005 most research, including health, uniform and risk research assumed all cohorts were male, with Robyn Cooper's work in 1997 an exception[59] From 2005 onwards haphazard yet valuable research about many aspects of women and firefighting, gender and disasters, in the Australian context was commenced, eg[60][61][62][63][64][65]

The percentage of career female firefighters remain at or below 5% of Australian fire services agencies, despite the history and activism noted above. Controversy remains acute.[66][67][68] Allegations of sexism[69][70] and bullying[71][72] remain. Arguments about suggested or actual changes to recruitment standards is now being supported by systematic research rather than fear-based sexist anecdotes,[73][74][75] although we do know that it is defined differently throughout the world.[76]

Unconscious and conscious cultural bias continues.

Austria

A female fire brigade was formed in 1912, with an initial recruitment of 60 women.[77] Women were admitted to volunteer fire brigades in 1978,[78] and as professionals in 1993.[79]

Canada

The oldest fire department and fire insurance company as well as the longest-serving firefighters in Canada originated in Nova Scotia. The terms "smoke-eaters" and "leather lungs" were used to describe firemen who had no need to come out for fresh air, and this success was attributed to male facial hair that was thought to act as a "watery sponge" that held fresh air. Since they lacked this facial hair, women were unable to earn these titles.[80]

In the late 1800s, many fire halls, including ones in Nova Scotia, united to compete in sports and physical challenges relating to fire fighting. However, it would not be until over one hundred years later, during the feminist movements of the 1960s, that the absence of women in contact sports was questioned.[80][81]

A "boys' club" culture existed in many fire departments, as the majority of the firefighters were white males. The firefighters were held to strict standards, and were fined (or could even be fired) for spitting on the floor, being late to meetings, and being drunk on or off duty. However, many of the firefighters would support each other by not reporting another member when they were intoxicated.[80]

In 1999, the Supreme Court of Canada ruled that a mandatory fitness test for those seeking to become firefighters in British Columbia unfairly discriminated against women. The test had been based on the physiology of male firefighters. The Court ruled that employers must show that any required workplace tests are necessary, and that there has been some effort to accommodate individuals.[5][6]

Female-focused camps to train young women in firefighting skills have been created by fire departments in Ottawa and London, Ontario, and have led to similar camps being established in the U.S.[82]

Currently, only 4% of firefighters in Canada are women.[83] Many female firefighters have reported facing resistance when they try to move up in rank. They often report feeling the need to be overqualified in order to compensate for their gender and to prove that they were hired based on merit and not simply an attempt at diversification.[84][85]

France

In 2015, 2.9% of firefighters were women, with 6.4% of these women holding the title of fire officer.[86]

Germany

Volunteer female firefighters worked in Berlin and Breslau during World War I but ceased at the end of the war. Women were again recruited during World War II, especially as drivers. This continued until 1955 when they had all been replaced by men. In the German Democratic Republic (GDR), women were extensively used both in support roles and as front-line firefighters. Women began to take on all roles in the 1980s. Female professional firefighters now number about 550 (1.3%), with approximately 80,000 volunteers (7%).[87]

Norway

The first documented female firefighters in Norway joined the fire services during the 1980s.[88][89] In 2011, 3.7% of the Norwegian firefighters were women.[90]

Hong Kong

The Hong Kong Fire Services Department started recruiting women for control and ambulance staff in the 1980s; however, the first firewoman was not hired until 1994.

As of 2003, there were 111 uniformed females, but only 8 were operational firefighters.[91]

India

In 2003, the Tamil Nadu Fire and Rescue Services appointed Priya Ravichandran as a Divisional Fire Officer, making her one of the first female fire officers in the country, and the first one to win the Anna Medal for Bravery.[92]

In 2009, a proposal was mooted in the Municipal Corporation Chandigarh to allow women into the fire services.[93]

In 2012, the Mumbai Fire Brigade inducted five women firefighters, making them the first in the history of the organisation.[94]

In 2013, the department inducted its second batch of women firefighters.[95]

Japan

As of 2003, the Tokyo Fire Department (TFD) - the second biggest fire department in the world - had 666 female firefighters, or 3.8% of the total.[91]

In 2009, as part of a recruitment drive, it was stated that there were 17,000 female fire service staff, though it is not clear how many of these were operational rather than support roles.[96]

In 2015, the TFD had 18,700 active firefighters.[86] Only 1,200 (6.4% of the operational force) were women.[86]

The first woman was appointed to the Kawasaki Fire Department rescue unit in 2016.[86]

Netherlands

Women firefighters have been serving in the Netherlands since at least 1939.[97]

In 2000, women accounted for 3.3% of professional firefighters.[98]

New Zealand

Overview

To be written

Notable moments

1979 Fire communications centre worker, Anne Barry applied to join the NZ Fire Service as a career firefighter and he application was rejected on the grounds of gender

1981 July Sapper Jan Graham of the Royal New Zealand Engineers becomes the NZ Army’s first full time female firefighter

1981 July 27 Anne Barry won her 2yr battle with the Fire Service Commission and was allowed to apply to join the NZFS as a career fire fighter[4]

1981 4 November Elizabeth England and Anne Barry completed the NZFS recruit course, with overall placings of 2nd and 3rd respectively, becoming New Zealand’s first female career firefighters, and the first female career firefighters in Australasia

1985 Julie Croswell was appointed as the third female firefighter

1988 Nella Booth[99] and Sheralee Rickaby[100] were appointed as the fourth equal female firefighters. Booth was appointed to Petone Station, Wellington Fire Region and Rickaby was appointed to Upper Hutt, Wellington Fire Region, of the NZ Fire Service

1979 November. A number of women competed for the first time in New Zealand at a provincial United Fire Brigades Waterways Competition – Tokomaru Bay, East Coast

1989 Christine Hewson became the New Zealand Fire Service’s first volunteer Station Officer of the Hawea Volunteer Fire Brigade

1993 July. Christine Hewson became the New Zealand Fire Service’s first female Chief Fire Officer (CFO) when she was appointed as Chief of the Lake Hawea Volunteer Fire Brigade. Christine had served in the Brigade since May 1979

1998 Nella Booth was appointed as the first career firefighter Station Officer (SO, Fire Safety) of the NZ Fire Service, Central Fire Station, Auckland

1998-2008 Nella Booth was Chair of New Zealand Fire Service Women

1999 Allana Ranui was appointed New Zealand Fire Service’s first Maori female CFO, for the Murupara Volunteer Fire Brigade

1999 Alison Timms was appointed action Chief Executive of the New Zealand Fire Service, holding the position until 2001

2001 28 April Rosemary Higgins becomes New Zealand’s first female 25yr Gold Star recipient. She joined the British Fire Service since 1959, and upon moving to New Zealand in 1975, she joined the Hamilton Fire Brigade in the Communications Centre. She was the only uniformed woman in Hamilton for nearly 17 years. When she retired from the Communication Centre, she joined the Pauanui Volunteer Fire Brigade

2001 May Nella Booth convened a group of career female firefighters in Auckland to discuss the possibility of setting up a support/network group. Many topics were discussed over the two days of the meeting, and one outcome was the formation of New Zealand Fire Service Women (NZFSW)

2005 Nella Booth (SO), Senior FF Megan Tate and (1 other female ff) attended the first Women in Firefighting Conference in Sydney as representatives of New Zealand Fire Service Women (NZFSW)

2006 Nella Booth (SO) joined the Steering Committee of the Australasian Women in Firefighting Conference, Sydney Australia, and gave the closing address of the conference

2008 September. Rochelle Martin was appointed as the New Zealand Fire Service’s first female career operational firefighter to hold the rank of Station Officer (SO)

2015 New Zealand Fire Service Women (NZFSW) was reformed as Women in Fire and Emergency New Zealand (WFENZ)

Pakistan

Shazia Parveen Jamali, who hails from Vehari District in Punjab, joined the Rescue 1122 emergency services as a firefighter in 2010.[101]

United Kingdom

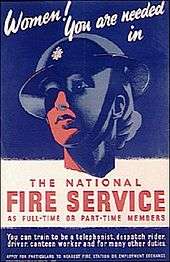

In Great Britain, Girton Ladies' College had an all-women's fire brigade from 1878 until 1932.[102][103][104] In 1887 it was reported that women employed in a cigar factory in Liverpool had been formed into a fire brigade, and had effectively extinguished a fire at the factory.[105] During World War I, women's brigades carried out firefighting and rescue in the South of England.[106] During the 1920s, women firefighting teams were employed by private fire brigades.[107] At the beginning of World War II, 5000 women were recruited for the Auxiliary Fire Service, rising to 7000 women in what was then the National Fire Service. Though trained in firefighting, women were not there for that purpose, but rather for such positions as driving and firewatching. Many received awards for heroism.[108]

In the modern era, some of the first women to participate in firefighting were based at Gordonstoun School near Elgin in Scotland. The school's staff and pupils had participated in a volunteer unit of the local Grampian Region Fire Brigade (GRFB) since the school's return from Wales in 1948.[109] In 1972, the school accepted girls as pupils for the first time and from 1975 women were accepted into the voluntary firefighting unit. They were not initially allowed to be official members of the GRFB, but could operate only within the school. The turning point took place in 1976, when the scale of a forest fire on Ben Aigan near Craigellachie on Speyside led the GRFB to seek volunteers from the local community to help fight the fire. Alongside personnel from local Royal Air Force bases, a group of trained women firefighters from Gordonstoun attended. The performance and endurance of this group over seven days and nights of firefighting led the GRFB to agree to allow women to take on official front-line firefighting roles for the first time.[110] The drought of the same year led to a call for extra firefighters and prompted other brigades to allow women to join. Mary Joy Langdon joined the East Sussex Fire Brigade on August 21 and was described by the press as Britain's first female firefighter.[3][111][112] In 1978, it was announced that females would be accepted into the fire service.[112]

In 2002, the Equal Opportunities Commission submitted a seven-page submission to the Independent Review of the Fire Service criticizing numerous practices which contributed to the extremely low recruitment of women and racial minorities in the fire service. In particular, the Commission highlighted the system of long day and night shifts, which likely discouraged women with children from applying, and the practice of only allowing those with firefighting experience to move into the higher ranks, which meant that control staff were ineligible.[12]

In 2011, Ann Millington became the first female Chief Fire Officer, taking charge of Kent Fire and Rescue Service.[113] In 2016, Rebecca Bryant was appointed to lead the Staffordshire Fire and Rescue Service; she was the first female CFO to be a former frontline firefighter.,[114] while Station Manager Sally Harper received the Queen's Fire Service Medal.[115] In 2017, Dany Cotton became Commissioner of the London Fire Brigade.[116]

As of 2017, there were 300 female firefighters in the London Fire Brigade, or 7% of the total.[117] As of March 2007, the proportion of women operational firefighters in the U.K. was 3.1%.[118]

United States

The first known female firefighter in the United States was a slave from New York named Molly Williams, who was said to be "as good a fire laddie as many of the boys," and fought fires during the early 1800s.[102][103] In the 1820s, Marina Betts was a volunteer firefighter in Pittsburgh.[119] Lillie Hitchcock was made an honorary member of the Knickerbocker Engine Company, No. 5., in San Francisco in 1863, and fought fires for some years after.

In the 1910s, there were women's volunteer fire companies in Silver Spring, Maryland, and Los Angeles, California.[103]

During World War I, many women entered the workforce to replace the men who were fighting overseas. This resulted in thousands of women working in traditionally male-dominated professions, though often in less physically-challenging and dangerous roles than their male counterparts might occupy. For example, the military hired approximately 11 000 women by 1918 for clerical work.[120]

In 1936 Emma Vernell became the first official female firefighter in New Jersey.[121]

During World War II, some women served as firefighters in the United States to replace male firefighters who joined the military; indeed, during part of the war, two fire departments in Illinois were all-female.[103] In 1942, the first all-female forest firefighting crew in California was created.[103]

There were all-female fire companies in Kings County, California, and Woodbine, Texas, in the 1960s. During the summer of 1971, an all-female Bureau of Land Management (BLM) firefighting crew fought fires in the wilds of Alaska. Furthermore, an all-female United States Forest Service firefighting crew fought fires in 1971 and 1972 in Montana.[103]

The first known female fire chief in the U.S. was Ruth E. Capello. Ruth Capello was born in 1922 and became fire chief of the Butte Falls fire department in Butte Falls, Oregon in 1973. She died at the age of 70 in 1992.[122] Sandra Forcier, the first known paid female firefighter (excluding forest firefighting) in the U.S., began working in North Carolina in 1973 for Winston-Salem Fire Department; she was a Public Safety Officer, a combination of police officer and firefighter.[123] The first woman to work solely as a paid firefighter (excluding forest firefighting) was Judith Livers, hired by the Arlington County, Virginia fire department in 1974.[103]

Brenda Berkman took legal action against a discriminating physical test of the New York City Fire Department in 1982. After winning the case, she and about 40 other women became the first female firefighters in the history of New York City.[124] Berkman was founder of the United Women Firefighters and also became the first openly gay person to be a professional firefighter.

The first female head of a career fire department, Chief Rosemary Bliss in Tiburon, California, became fire chief in 1993.[125][126][127]

In 2002, approximately 2% of all firefighters were female in the United States.[126]

Sarinya Srisakul was the first Asian-American woman to be hired by the New York City Fire Department in 2005.[86]

In 2013, Los Angeles Mayor Eric Garcetti vowed to make sure that 5% of the Los Angeles Fire Department's firefighters were women by 2020. As of 2018 3.1% of the department's firefighters are women.[128]

In 2015, the New York City Fire Department had 58 women, representing less than 0.5% of the 10,000 active operational firefighters.[86] Regina Wilson also became the first woman president of the Vulcan Society (African-American Firefighters Association).[86]

Terminology

For much of the last century, firefighting was a male-dominated or exclusively male profession. As such, firefighters were commonly called "firemen", an informal title still used by some civilians today. The title "firefighter" has become the universally accepted terminology in NFPA training materials and is used by English speaking professionals and trained volunteers as both the basic rank and overall job title that is often paired with the addition of a firefighter's EMT certification level (e.g., "Firefighter-Paramedic Jane Doe").[129][130]

Challenges

Since women have only begun to be widely hired or accepted as volunteer firefighters in the last 30–40 years, there have been many difficult adjustments for the fire service. In many places, the fire service is steeped in tradition and formalized, paramilitary relationships.[131] A 1998 article in Fire Engineering noted that firefighters tend to form tight-knit communities which value "strength, courage, and loyalty" but can be "resistant to change".[132] Even if women are socially accepted members of the fire service, it is on the basis of gendered assumptions that they will bring more balanced decision making and nurturing qualities to a team of firefighters.[133]

Health

In 2017, a study of female firefighters' occupational stress in the U.S. found that 40% of the women had engaged in binge drinking in the previous month, and 16.5% screened positive for problem drinking. According to the study, "problem drinkers were more than 2.5 times as likely to have been diagnosed with a depressive disorder or to have symptoms of post-traumatic stress." Those with less than seven years of service were the most likely to report issues with drinking.[134]

In Canada, a lack of health coverage is often an issue for female firefighters in certain provinces. Although many cancers are covered as known occupational risks because of overexposure to fire, smoke, and toxic fumes, breast cancer is not yet covered nationwide.[135][136]

Although women in the fire service are generally more healthy and fit than their male coworkers as well as women in the wider population, they experience higher rates of miscarriage and preterm births.[137] This may be linked to occupational hazards such as environmental toxins,[138] heavy lifting, and irregular shift work.[139] In 2012, the International Association of Firefighters in the U.S. recommended that all fire departments create policies on pregnancy and/or maternity leave,[140] but in a study in 2018 nearly a quarter of female firefighters reported that their departments had no such policies.[137]

Facilities and equipment

One major hurdle to entrance into firefighting for women was the lack of facilities. The immediate problem of sleeping quarters and bathing areas had to be solved before women could participate fully in firefighting as an occupation and as a culture. Communal showers and open bunk halls were designed for men only. Today, fire stations, as public entities, must either follow gender equity law or face judicial injunctions; thus, they are now designed to accommodate firefighters of both genders. However, some female firefighters still face issues related to their gender.

A pan-Canadian study found that equipment, services and resources for female firefighters are often inadequate. Gear is often not made for women and offsite there is often no proper facilities for feminine hygiene needs.[141][142]

Discrimination

A 2015 study on women in the wildland firefighting profession in Australia found that 55% reported seeing gender discrimination of others, while 45% reported experiencing it themselves.[133]

Sexual dimorphism

There have been occasional charges of some departments lowering standards so that they could hire more women. In 2005, Laura Chick (the LA City Controller) stated in a report that Fire Chief Bamattre lowered physical requirements for female recruits and ordered that women be passed even if they failed their tests.[143] However, many female firefighters reject any form of accommodation or special treatment, in part because they wish to prove themselves in the same way as their male counterparts, and in part because they fear it will make them a target for harassment.[84][144]

Sexual harassment

Studies have found that women working in male-dominated professions, such as firefighting, experience more sexual harassment that those working in traditional female professions.[145][146] This increased rate of harassment is worsened further when women are in the minority, as they often are in the fire service, because the majority group in such circumstances tends to view those in the minority as token representatives of their group rather than individuals.[145]

In a survey conducted by Women in the Fire Service in 1995, 551 women in fire departments across the U.S. were asked about their experiences with sexual harassment and other forms of job discrimination. Eighty-eight percent of fire service women responding had experienced some form of sexual harassment at some point in their fire service careers or volunteer time. Nearly 70% of the women in the survey said that they were experiencing ongoing harassment at the time of the study. Of the 339 women who indicated that they had complained about harassment, only a third (115 women) listed positive-only outcomes: investigating/taking care of the problem and disciplining the harasser. Twenty-six percent said that they were retaliated against for having reported the incident.[147]

Many Canadian female firefighters admit to experiencing some levels of systemic gendered violence such as sexual harassment and assault, which includes groping and being solicited for sexual services.[148][149] Female firefighters who experience harassment have been found to be more hesitant to report it because they fear negative consequences such as exclusion and the exacerbation of the harassment.[150][151] Many female firefighters have reported avoiding feminine apparel such as high heels, dresses, and makeup when around their male coworkers, for fear of being hypersexualized and becoming the target of sexual assault or harassment.[151]

In 2016, a Canadian male firefighter was charged with two counts of sexual assault and one count of assault with a weapon in connection with his harassment of a female coworker.[149]

An American nationwide study found that the majority of female firefighters that experience sexual harassment do not report it to their superiors, in many instances because the supervisor was involved in or already knew about the behavior. When harassment was reported, no formal action was taken in the majority of cases.[152]

Sexually harassed female firefighters are significantly more likely to report experiencing job stress.[152]

See also

- Dany Cotton – British. First woman to win the Queen's Fire Service Medal, highest ranking operational female firefighter in the country.[153]

- Lillie Hitchcock Coit – volunteer firefighter in San Francisco in the 1920s and on.

- Molly Williams – first known female firefighter in the United States.

- Women in the military

References

- 1 2 "Burning questions: Ancient Aboriginal fire techniques helping farmers, scientists". 18 April 2018.

- ↑ "IFD Black History". Archived from the original on 2007-01-09. Retrieved 2007-01-12.

- 1 2 Sunday Express August 20, 2006, p 35 "I was Britain's first female firefighter"

- 1 2 Wauchop, Jessica (21 September 2007). "First woman firefighter tells of her blazing passion" – via www.nzherald.co.nz.

- 1 2 Lawton, Valerie (September 10, 1999). "Women win new deal on workplace standards ; Top court rules that male fitness levels can't apply to females". Toronto Star.

- 1 2 "British Columbia (Public Service Employee Relations Commission) v. BCGSEU - SCC Cases (Lexum)". scc-csc.lexum.com. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ "Fire and rescue authorities: operational statistics bulletin for England 2015 to 2016" (PDF). Home Office. 27 October 2016. Retrieved 29 August 2018.

- ↑ "Police workforce, England and Wales, 31 March 2016" (PDF). Gov.uk. 21 July 2016. Retrieved 18 July 2017.

- ↑ Health & Care Professionals Council: Gender breakdown of paramedics

- ↑ "UK armed forces biannual diversity statistics: 2017". www.gov.uk. 2017. Retrieved 2017-12-12.

- ↑ London Fire Brigade recruitment report

- 1 2 Turner, David (October 30, 2002). "Equality watchdog attacks fire service policies on women". Financial Times.

- ↑ "AIATSIS map of Indigenous Australia". 3 June 2015.

- ↑ "Indigenous fire management practices benefit Country and Traditional Owners".

- ↑ "What-Shall-We-Do-With-Our-Girls.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Women in Fire Fighting (Australia) - an Archive: The Amazons c1901-1903".

- ↑ "Armidale FireBrigade.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ https://mgnsw.org.au/organisations/museum-fire/

- ↑ "NEGS FB.jpg". Google Docs.

- ↑ TROVE 43 digitized newspaper articles in TROVE about the Amazons 1902-1905

- ↑ "Dubbo parade.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ UNE Archives and Heritage Centre the original images of the Amazon Ladies Fire Brigades (framed memorial photographic collection)

- ↑ article with photographs written by the Sydney Mail and New South Wales Advertiser (NSW : 1871 - 1912), Wednesday 8 February 1905, page 353.

- ↑ Merilyn Childs (29 January 2012). "Key Note Address, Women in Firefighting Conference 2006".

- ↑ "TAS.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Tas Churchill.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "QLD.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ Underwood, Roger (2017). Women of the Forest. York Gum Publishing,. ISBN 0994227124.

- ↑ "WA.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Board of Governors.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Women's Fire Auxiliary (Wagga Wagga)". 7 June 2010.

- ↑ "Newcastle Womens FA.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Newcastle womens 1.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Newcastle 2.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Wollongong Womens.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Broken Hill.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Safety helmet : New South Wales Women's Fire Auxiliary". www.awm.gov.au.

- ↑ McQuillan, Ernest Mervyn. "SYDNEY, NSW. 1946-07-11. MISS DOROTHY BARRETT, WHO WAS ORGANISER AND CHIEF OF THE WOMEN'S FIRE AUXILIARY, STANDING BESIDE A FIRE TRUCK AT FIRE BRIGADE HEADQUARTERS, CASTLEREAGH STREET" – via Trove.

- ↑ "Women's Fire Auxiliary press cuttings book". State Records Authority of New South Wales. 6 June 2018 – via Trove.

- ↑ "SA.pdf". Google Docs.

- ↑ "Recreated historic uniforms - women in fire fighting".

- ↑ https://www.flickr.com/photos/72653074@N08/albums/72157633017289699

- ↑ Cronin, Glen (6 June 2018). "History of the Morphett Vale Ladies Auxiliary". [Morphett Vale, S. Aust. : The Auxiliary – via Trove.

- ↑ Brient, Toni (22 December 2014). "'Backbone of brigade'".

- ↑ "Women of the Forest: historian Roger Underwood's book pays tribute to women who worked or lived in WA forests - Community News Group". 1 November 2017.

- ↑ "Post World War II: 1946-1970 - Striking Women". www.striking-women.org.

- ↑ http://moodle.pmaclism.catholic.edu.au/pluginfile.php/19346/mod_resource/content/1/Text%20-%20Womens%20Changing%20Rights.pdf

- ↑ "Federal Register of Legislation - Australian Government". www.legislation.gov.au.

- ↑ "Women half of NSW firefighting graduates for first time". 16 December 2016.

- ↑ https://www.humanrights.gov.au/news/speeches/firing-women

- ↑ "Women in Fire Fighting (Australia) - an Archive: WIFF Conference Archives 2006".

- ↑ "npws_timeline.jpg". Google Docs.

- ↑ "AJEM Counting women in the Australian fire services". ajem.infoservices.com.au.

- ↑ http://womeninfirefighting.blogspot.com/p/blog-page.html

- ↑ https://onlinelibrary.wiley.com/doi/pdf/10.1111/gwao.12010

- ↑ http://s3-ap-southeast-2.amazonaws.com/wh1.thewebconsole.com/wh/6807/images/Gender-balance-overview.pdf

- ↑ "Fire and Emergency Male Champions of Change - Male Champions of Change".

- ↑ https://www.wafa.asn.au/past-conferences.html

- ↑ (https://www.informit.org/researchers/who-is-informit), Informit - RMIT Training PTY LTD. "Crossing gender boundaries [Women firefighters and male nurses.]". Refractory Girl: A Women's Studies Journal (52).

- ↑ (https://www.informit.org/researchers/who-is-informit), Informit - RMIT Training PTY LTD (1 May 2006). "Counting Women in the Australian Fire Services". Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The. 21 (2).

- ↑ (https://www.informit.org/researchers/who-is-informit), Informit - RMIT Training PTY LTD (1 August 2005). "Australia's Women Volunteer Fire Fighters: A Literature Review and Research Agenda". Australian Journal on Volunteering. 10 (2).

- ↑ (https://www.informit.org/researchers/who-is-informit), Informit - RMIT Training PTY LTD (1 July 2010). "Women Firefighters' Experiences in the Western Australian Volunteer Bush Fire Service". Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The. 25 (3).

- ↑ (https://www.informit.org/researchers/who-is-informit), Informit - RMIT Training PTY LTD (1 April 2013). "Firey women program". Australian Journal of Emergency Management, The. 28 (2).

- ↑ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/08941920.2016.1171938

- ↑ https://www.tandfonline.com/doi/abs/10.1080/07420528.2018.1466793

- ↑ Schneiders, Nick Toscano, Ben (11 March 2016). "Metropolitan Fire Brigade and union face off over female firefighter intake". The Age.

- ↑ "Female firefighters fired up about new gender quota".

- ↑ Back, Alexandra. "Aspiring male firefighter alleges discrimination as more women recruited". Canberra Times.

- ↑ "Female firefighters' shocking claims of sexism at work". honey.nine.com.au.

- ↑ Farmer, Ben (16 October 2017). "Stop calling us 'firemen' because it's sexist, says chief of London Fire Brigade" – via www.telegraph.co.uk.

- ↑ Baker, Nick McKenzie, Farrah Tomazin, Richard (5 March 2018). "The report the firefighters' union did not want you to see". The Age.

- ↑ Baker, Nick McKenzie, Richard (16 October 2017). "Sexual harassment, bullying, endemic for women in Country Fire Authority, says report". The Age.

- ↑ Nazari, Goris; MacDermid, Joy C.; Sinden, Kathryn E.; Overend, Tom J. (6 June 2018). "The Relationship between Physical Fitness and Simulated Firefighting Task Performance". Rehabilitation Research and Practice. 2018: 1–7. doi:10.1155/2018/3234176.

- ↑ Blacker, S. D.; Rayson, M. P.; Wilkinson, D. M.; Carter, J. M.; Nevill, A. M.; Richmond, V. L. (1 October 2015). "Physical employment standards for UK fire and rescue service personnel". Occupational Medicine. 66 (1): 38–45. doi:10.1093/occmed/kqv122.

- ↑ "Employment Standards for Australian Urban Firefighters: Erratum". Journal of Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 57 (12): e159. 1 December 2015. doi:10.1097/JOM.0000000000000643 – via journals.lww.com.

- ↑ http://hadmernok.hu/archivum/2008/3/2008_3_cziva.pdf

- ↑ Daily Mirror 9 July 1912 A New Occupation for Girls - Firewomen in Austria

- ↑ regionaut.meinbezirk.at Eine der ersten Feuerwehr-Frauen ist im Ruhestand! (one of the first women firefighters is retiring)

- ↑ de.wikipedia.org Österreich Frauen in der Feuerwehr

- 1 2 3 Parker, M. The smoke-eaters: A history of firefighting in Nova Scotia c. 1750-1950. Halifax: Nimbus Publishing.

- ↑ Lenskyj, H. (1986). Out of bounds: Women, sport, and sexuality. Toronto: Canadian Scholar's Press.

- ↑ Botelho-Urbanski, Jessica (August 10, 2016). "Rookie firefighters battle blazes and stereotypes: Mississauga's first female firefighter encouraging young recruits with Camp Ignite". Toronto Star.

- ↑ Statistics Canada, 2010.

- 1 2 Poulin, C., Gouliquer, L., McWilliams, J., Young, P., Tucker, W., & Moore, A. (2016). Female firefighters in leadership roles: “Where is the man in charge?” Poster-presentation at the UNB Research Showcase, Fredericton, Canada, (30 September).

- ↑ Atkinson, Cathryn (November 8, 2007). "Woman earned deputy fire chief job on merit, Richmond mayor says". Globe & Mail.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 https://www.wafa.asn.au/wh/6807/images/Churchill-Report-Version-2-April-17.docx

- ↑ "Netzwerk Feuerwehrfrauen".

- ↑ http://www.vg.no/sport/ski/artikkel.php?artid=217803; in Norwegian

- ↑ http://www.ta.no/nyheter/article1198918.ece; in Norwegian

- ↑ http://www.nrk.no/sorlandet/sliter-med-a-fa-kvinner-inn-i-brannvesenet-1.12325872 (in Norwegian)

- 1 2 Tam, T-k, (2003) A study of the recruitment and selection of female firefighters in the Hong Kong Special Administrative Region: A comparative perspective (masters thesis) University of Hong Kong

- ↑ "Women-Power: Serving to save". The Hindu. May 1, 2012. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ↑ Sandhu, Khushbu (Aug 6, 2009). "Soon, women firefighters to take charge". The Indian Express. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ↑ "Mumbai gets its first women firefighters". Times of India. January 3, 2012. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ↑ K, Manikandan (November 8, 2013). "Second batch of women firefighters begins training". The Hindu. Retrieved 2013-12-05.

- ↑ Japan Today Feb 12, 2009 Megumi Yasu serves as poster girl for female firefighter recruitment drive

- ↑ https://www.openbeelden.nl The women's fire brigade gives a demonstration

- ↑ Shizue Tomoda (2002) Public emergency services: social dialogue in a changing environment(ILO) ISBN 92-2-113399-0

- ↑ https://drive.google.com/file/d/1-ma-MM9ybhsIOW9ZVPMqm8vhoIjzn79O/view?usp=sharing

- ↑ https://drive.google.com/file/d/19vKIoS-I8QJgegfj_Lke_lRk2K7zwA8c/view?usp=sharing

- ↑ "Never back down: Pakistan's first female firefighter arrives". www.pakistantoday.com.pk.

- 1 2 "Women Firefighters - fighthefire.info". www.fightthefire.info.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 "International Association of Women in Fire & Emergency Services". I-women.org. Retrieved 2017-02-23.

- ↑ "1900 - Biography of Lillie Hitchcock-Coit". Sfmuseum.org. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- ↑ The Forest Republican., May 11, 1887, page 1, citing the London publication Fireman

- ↑ British Pathe Women's Fire Brigade

- ↑ Daily Mirror 24 Sep 1923, 26 May 1924, 6 Oct 1924

- ↑ London Fire Brigade Women in the Fire Service

- ↑ Hollis, Jill, ed. (2011). "The Fire Service". Gordonstoun An Enduring Vision. London: Third Millennium Publishing. p. 146. ISBN 9781906507299.

- ↑ Hollis, Jill, ed. (2011). "The Fire Service". Gordonstoun An Enduring Vision. London: Third Millennium Publishing. p. 148. ISBN 9781906507299.

- ↑ London Fire Brigade news release 26 Feb 2016 UK’s first woman firefighter hosts Royal fire safety day at famous Wormwood Scrubs Pony Centre

- 1 2 The Argus 19 Aug 2016 Sussex's first fire woman on her days in the brigade

- ↑ "Kent appoints first female Chief Fire Officer - FIRE". FIRE.

- ↑ Staffordshire Fire and Rescue Service 24/06/2016 Fire Service Gets Glowing Report

- ↑ London Fire Brigade news release 11 June 2016 History making woman firefighter recognised in Queen’s birthday honours

- ↑ http://www.london-fire.gov.uk/news/LatestNewsReleases_interim-fire-commissioner-takes-charge.asp#.WGjybrGca9Y

- ↑ London Fire Brigade news release 6 Feb 2017 'Brigade needs more women', warns London’s fire chief

- ↑ UK Government Fire and Rescue Service Equality and Diversity Strategy 2008 - 2018

- ↑ "Marinwood Fire Department | The History of Volunteer Firefighting". Marinwoodfire.org. 1939-05-30. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- ↑ Gavin, L. (2014). American women in world war one: They also served. Colorado: University Press of Colorado.

- ↑ "Emma Vernell | Borough of Red Bank, New Jersey 07701". redbanknj.org. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- ↑ "Reading Eagle - Google News Archive Search". news.google.com.

- ↑ "History of Women in Firefighting".

- ↑ Reynolds, Eileen (2016-09-09). "On 9/11, Women Were Heroes Too". New York University. Retrieved 2017-01-29.

- ↑ another studiodog.com website (1973-07-01). "International Association of Women in Fire & Emergency Services". I-women.org. Retrieved 2011-12-12.

- 1 2 Associated Press March 17,2002 All-male image burns firefighters

- ↑ Mankind, Other Lazy Terms, Return to News Pages – 2011 Women's eNews Inc.

- ↑ "Los Angeles Mayor Struggling to Expand the Number of Female Firefighters". www.fireengineering.com.

- ↑ "300 Plus Abbreviations & Acronyms Every Firefighter Should Know".

- ↑ http://www.carmel.in.gov/modules/showdocument.aspx?documentid=195

- ↑ The Guardian 16 April 2012 "Burning issues for female firefighters"

- ↑ "Fire/EMS Merger: An Examination of Cultural Differences". Fire Engineering. 1998-09-01. Retrieved 2018-09-28.

- 1 2 Eriksen, Christine (2015). "Gendered Dynamics of Wildland Firefighting in Australia". Society & Natural Resources: An International Journal. 29 (11): 1296–1310.

- ↑ Haddock, Christopher K.; Poston, Walker S. C.; Jahnke, Sara A.; Jitnarin, Nattinee (2017). "Alcohol Use and Problem Drinking among Women Firefighters". Women's Health Issues. 27 (6): 632–638.

- ↑ Pruss, V. (May 16, 2017). "Woman says breast cancer linked to 17 years as firefighter". CBC News.

- ↑ "Maladies professionnelles présumées chez les pompiers" (PDF). Regroupement des Associations de Pompiers du Québec (RAPQ). 2016.

- 1 2 Jahnke, Sara A. (June 2018). "Maternal and Child Health Among Female Firefighters in the U.S.". Maternal and Child Health Journal. 22 (6): 922–931.

- ↑ Feodor Nilsson, S; Andersen, PK; Strandberg-Larsen, K; Nybo Andersen, A-M (2014-02-19). "Risk factors for miscarriage from a prevention perspective: a nationwide follow-up study". BJOG: An International Journal of Obstetrics & Gynaecology. 121 (11): 1375–1385. doi:10.1111/1471-0528.12694. ISSN 1470-0328.

- ↑ Wong, E. Y.; Ray, R. M.; Gao, D.-L.; Wernli, K. J.; Li, W.; Fitzgibbons, E. D.; Camp, J. E.; Astrakianakis, G.; Heagerty, P. J. (2009-03-01). "Dust and chemical exposures, and miscarriage risk among women textile workers in Shanghai, China". Occupational and Environmental Medicine. 66 (3): 161–168. doi:10.1136/oem.2008.039065. PMC 2862777. PMID 18805889.

- ↑ "Welcome to the IAFF Website" (PDF). www.iaff.org. Retrieved 2018-05-25.

- ↑ Gouliquer, Lynn (2001). "Women and the Canadian military". Atlantis. 26 (1): 31–76.

- ↑ Lesmana, M., Poulin, C., & Gouliquer, L. (2015). The experience of female firefighters: Confronting Ageism and Sexism. Poster-presentation at the 76th annual convention of the Canadian Psychological Association, Ottawa, Canada, June 3–6.

- ↑ Pelisek, Christine (23 January 2008). "Women Firefighters: The Gender Boondoggle".

- ↑ Mulley Macdonald, Sherry (August 4, 2016). "Women in non-traditional roles - and loving it; Firefighting not just for men". Chronicle Herald.

- 1 2 Gutek, Barbara A.; Morasch, Bruce (1982). "Sex Ratios, Sex-Role Spillover and Sexual Harassment of Women at Work". Journal of Social Issues. 38 (4): 55–74.

- ↑ LaFontaine, Edward; Tredeau, Leslie (1986). "The Frequency, Sources and Correlates of Sexual Harassment Among Women in Traditional Male Occupations". Sex Roles. 15 (7/8): 433–442.

- ↑ "International Association of Women in Fire & Emergency Services". 14 August 2009.

- ↑ Gerhardt, E. (2017). Women under fire: The negative treatment of female firefighters. (Unpublished honours thesis). University of New Brunswick: Fredericton, NB.

- 1 2 Nasser, S. (November 30, 2016). "Toronto firefighter charged with sexual assault after allegations by female co-worker". CBC News.

- ↑ Poulin, C., Gouliquer, L., & McWilliams, J. (2017). Othering of full-time and volunteer female firefighters in the Canadian Fire Services. Manuscript in preparation.

- 1 2 McWilliams, J., Poulin, C., & Gouliquer L. (2017). Symposium: New Rules, Same Results: Othering of volunteer and full-time female firefighters in Canada. 78th annual convention of the Canadian Psychological Association, Toronto, Ontario, June 8–10.

- 1 2 Rosell, E.; Miller, K. (1995). "Firefighting Women and Sexual Harassment". Public Personnel Management. 24 (3): 339–339.

- ↑ International Women's Day 2010

External links

- International Association of Women in Fire & Emergency Services

- Women in the Fire Service, Inc.

- United Women Firefighters Collection (WAG.057) Tamiment Library & Robert F. Wagner Labor Archives, New York University