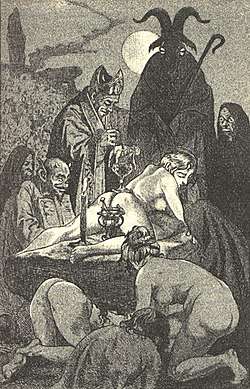

Witches' Sabbath

.jpg)

The Witches' Sabbath is a meeting of those who practice witchcraft and other rites. Distinguishable features that are typically contained within a Witches' Sabbat are assembly by foot, beast, or flight, a banquet, dancing and cavorting, and sexual intercourse.[1][2]

European records indicate cases of people being accused or tried for taking part in Sabbat gatherings, from the Middle Ages to the 17th century or later.

Origins

Etymology

The English word "sabbath" is of obscure etymology and late diffusion, and local variations of the name given to witches' gatherings were frequent.[3] "Sabbath" came indirectly from Hebrew שַׁבָּת (Shabbath, "day of rest"). In modern Judaism, Shabbat is the rest day celebrated from Friday evening to Saturday nightfall; in modern Christianity, Sabbath refers to Sunday, or to a time period similar to Sabbath in the seventh-day church minority. In connection with the medieval beliefs in the evil power of witches and in the malevolence of Jews and Judaizing heretics (both being Sabbathkeepers),[4] satanic gatherings of witches were by outsiders called "sabbats", "synagogues", or "convents".[3]

Although allusions to Sabbaths were made by the Catholic Canon law since about 905, the first book that mentions the Sabbath is, theoretically, Canon Episcopi, included in Burchard of Worms's collection in the 11th century. The Canon Episcopi alleged that "Diana's rides," (by the name of the Roman goddess of the hunt) were false, and that these spirit travels did not occur in reality. Errores Gazariorum later evoked the Sabbat, in 1452.

In the 13th century the accusation of participation in a Sabbath was considered very serious. Helping to publicize belief in and the threat of the Witches' Sabbath was the extensive preaching of the popular Franciscan reformer, Saint Bernardino of Siena (1380–1444), whose widely circulating sermons contain various references to the sabbath as it was then conceived and hence represent valuable early sources into the history of this phenomenon.[5] Some allusions to meetings of witches with demons are also made in the Inquistors' manual of witch-hunting, the Malleus Maleficarum (1486). Nevertheless, it was during the Renaissance when Sabbath folklore was most popular, more books on them were published, and more people lost their lives when accused of participating. Commentarius de Maleficiis (1622), by Peter Binsfeld, cites accusation of participation in Sabbaths as a proof of guiltiness in an accusation for the practice of witchcraft.

Ritual elements

Bristol University's Ronald Hutton has encapsulated the witches' sabbath as an essentially modern construction, saying:

[The concepts] represent a combination of three older mythical components, all of which are active at night: (1) A procession of female spirits, often joined by privileged human beings and often led by a supernatural woman; (2) A lone spectral huntsman, regarded as demonic, accursed, or otherworldly; (3) A procession of the human dead, normally thought to be wandering to expiate their sins, often noisy and tumultuous, and usually consisting of those who had died prematurely and violently. The first of these has pre-Christian origins, and probably contributed directly to the formulation of the concept of the witches’ sabbath. The other two seem to be medieval in their inception, with the third to be directly related to growing speculation about the fate of the dead in the 11th and 12th centuries."[6]

The book Compendium Maleficarum (1608) by Francesco Maria Guazzo illustrates a typical sabbath as "the attendants riding flying goats, trampling the cross, and being re-baptised in the name of the Devil while giving their clothes to him, kissing his behind, and dancing back to back forming a round". Other elements mentioned include the casting of powerful spells, orgies, and a Black Mass.

According to Hans Baldung Grien (ca 1484–1545) and Pierre de Rostegny, aka De Lancre (1553–1631), human flesh was eaten during Sabbats, preferably children, and also human bones stewed in a special way. Other descriptions add that human fat, especially that of unbaptised children, was used to make an unguent – the flying ointment – that enabled the witches to fly [see subsection below].

Location

According to folklore, the Sabbat was most often celebrated in isolated places, preferably forests or mountains. Some famous places where these events were said to have been celebrated are Brittany, Puy-de-Dôme (France), Blå Jungfrun (Sweden), Blocksberg, Melibäus, the Black Forest, (Germany), the Bald Mountain (Poland), Vésztő, Zabern, Kispest (Hungary), Macizo de Anaga in Tenerife and Zugarramurdi (Spain), Carignano, Benevento, San Colombano al Lambro (Italy) and more. It was also said that Stonehenge (England) was a place for Sabbats. Sabbats take place at Alderley Edge, Cheshire. In the Basque country the Sabbat (there called Akelarre, or 'field of the goat') was said to be celebrated in isolated fields. In East Slavic folklore, the common name for the Sabbat mountain is Lysa Hora ("Bald Mountain).

Dates

Some commonly mentioned dates were February 1 (to some February 2), Easter, May 1 (Great Sabbat, Walpurgis Night), August 1 (Lammas), November 1 (Halloween, commencing on October 30's eve), and Christmas. Other less frequently mentioned dates were Good Friday, January 1 (day of Jesus' Crucifixion), June 23 (Saint John's Eve), December 21 (St. Thomas), and Corpus Christi. and October 3.

The modern Sabbats that many Wiccans and Neo-Pagans now follow are: Imbolc (February 2), Ostara (Spring Equinox), Beltane (May 1), Litha (Summer Solstice), Lammas (August 1), Mabon (Autumn Equinox), Samhain (October 31) and Yule (Winter Solstice). (See also Wheel of the Year)

According to the testimonies of benandanti and similar European groups (see below), common dates for gatherings are during the weeks of the Ember days, during the twelve days of Christmas or at Pentecost.

Depictions in various art forms

As referenced earlier, Hawthorne seems to have been describing a witches' sabbath and the surrounding activity in his short story, "Young Goodman Brown." Musically, the supposed ritual has been used as inspiration for such works as Night on Bald Mountain by Modest Mussorgsky and the fifth movement of Hector Berlioz's Symphonie Fantastique.

In film, Robert Eggers' 2015 The Witch depicts a celebration of this ritual during the movie's climax. Also, Rob Zombie's The Lords of Salem incorporates such imagery as flashbacks into the titular town's backstory.

Depictions in painting include the following:

- The Witches' Sabbath by Hans Baldung (1510)

- Witches' Sabbath by Frans Francken (1606)

- Witches' Sabbath in Roman Ruins by Jacob van Swanenburgh (1608)

- Witches' Flight by Francesco Maria Guazzo (1626) Compendium maleficarum

- Witches' Sabbath by Francisco Goya (1798) Museum of Lázaro Galdiano

- Witches' Flight by Francisco Goya (1798) Museo del Prado

- Witches' Sabbath or The Great He-Goat by Francisco Goya (1823) Museo del Prado

- The Vision of Faust by Luis Ricardo Falero (1878)

- Muse of the Night (Witches' Sabbath) by Luis Ricardo Falero (1880)

Disputed accuracy of the accounts

In spite of the number of times that authorities retold stories of the sabbat, modern researchers have been unable to find any corroboration that any such event ever occurred.[7] The historian Scott E. Hendrix presents a two-fold explanation for why these stories were so commonly told in spite of the fact that sabbats likely never actually occurred in his study "The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat." First, belief in the existence of witches was widespread in late medieval and early-modern Europe. Many religious authorities believed there was a vast underground conspiracy of witches who were responsible for the horrific famines, plague, warfare, and problems in the Catholic Church that became endemic in the fourteenth century.[7] By blaming witches, religious authorities provided a handy scapegoat for those who might otherwise question God's goodness. Having prurient and orgiastic elements ensured that these stories would be relayed to others.[8]

In effect, the sabbat acted as an effective 'advertising' gimmick, causing knowledge of what these authorities believed to be the very real threat of witchcraft to be spread more rapidly across the continent.[7] That also meant that stories of the sabbat promoted the hunting, prosecution, and execution of supposed witches.

The descriptions of Sabbats were made or published by priests, jurists and judges who never took part in these gatherings, or were transcribed during the process of the witchcraft trials. That these testimonies reflect actual events is for most of the accounts considered doubtful. Norman Cohn argued that they were determined largely by the expectations of the interrogators and free association on the part of the accused, and reflect only popular imagination of the times, influenced by ignorance, fear, and religious intolerance towards minority groups.[9]

_-_The_Witches'_Sabbath.jpg)

Some of the existing accounts of the Sabbat were given when the person recounting them was being tortured.[10] and so motivated to agree with suggestions put to them.

Christopher F. Black claimed that the Roman Inquisition’s sparse employment of torture allowed accused witches to not feel pressured into mass accusation. This in turn means there were fewer alleged groups of witches in Italy and places under inquisitorial influence. Because the Sabbath is a gathering of collective witch groups, the lack of mass accusation means Italian popular culture was less inclined to believe in the existence of Black Sabbath. The Inquisition itself also held a skeptical view toward the legitimacy of Sabbath Assemblies.[11]

Many of the diabolical elements of the Witches' Sabbath stereotype, such as the eating of babies, poisoning of wells, desecration of hosts or kissing of the devil's anus, were also made about heretical Christian sects, lepers, Muslims, and Jews.[3] The term is the same as the normal English word "Sabbath" (itself a transliteration of Hebrew "Shabbat", the seventh day, on which the Creator rested after creation of the world), referring to the witches' equivalent to the Christian day of rest; a more common term was "synagogue" or "synagogue of Satan"[12] possibly reflecting anti-Jewish sentiment, although the acts attributed to witches bear little resemblance to the Sabbath in Christianity or Jewish Shabbat customs. The Errores Gazariorum (Errors of the Cathars), which mentions the Sabbat, while not discussing the actual behavior of the Cathars, is named after them, in an attempt to link these stories to an heretical Christian group.[13]

Christian missionaries' attitude to African cults was not much different in principle to their attitude to the Witches' Sabbath in Europe; some accounts viewed them as a kind of Witches' Sabbath, but they are not.[14] Some African communities believe in witchcraft, but as in the European witch trials, people they believe to be "witches" are condemned rather than embraced.

Possible connections to real groups

Other historians, including Carlo Ginzburg, Éva Pócs, Bengt Ankarloo and Gustav Henningsen hold that these testimonies can give insights into the belief systems of the accused. Ginzburg famously discovered records of a group of individuals in northern Italy, calling themselves benandanti, who believed that they went out of their bodies in spirit and fought amongst the clouds against evil spirits to secure prosperity for their villages, or congregated at large feasts presided over by a goddess, where she taught them magic and performed divinations.[3] Ginzburg links these beliefs with similar testimonies recorded across Europe, from the armiers of the Pyrenees, from the followers of Signora Oriente in fourteenth century Milan and the followers of Richella and 'the wise Sibillia' in fifteenth century northern Italy, and much further afield, from Livonian werewolves, Dalmatian kresniki, Hungarian táltos, Romanian căluşari and Ossetian burkudzauta. In many testimonies these meetings were described as out-of-body, rather than physical, occurrences.[3]

Role of topically-applied hallucinogens

Magic ointments...produced effects which the subjects themselves believed in, even stating that they had intercourse with evil spirits, had been at the Sabbat and danced on the Brocken with their lovers...The peculiar hallucinations evoked by the drug had been so powerfully transmitted from the subconscious mind to consciousness that mentally uncultivated people...believed them to be reality.[15]

Carlo Ginzburg's researches have highlighted shamanic elements in European witchcraft compatible with (although not invariably inclusive of) drug-induced altered states of consciousness. In this context, a persistent theme in European witchcraft, stretching back to the time of classical authors such as Apuleius, is the use of unguents conferring the power of 'flight' and 'shape-shifting'.[16] A number of recipes for such 'flying ointments have survived from early modern times, permitting not only an assessment of their likely pharmacological effects – based on their various plant (and to a lesser extent animal) ingredients – but also the actual recreation of and experimentation with such fat or oil-based preparations.[17] It is surprising (given the relative wealth of material available) that Ginzburg makes only the most fleeting of references to the use of entheogens in European witchcraft at the very end of his extraordinarily wide-ranging and detailed analysis of the Witches Sabbath, mentioning only the fungi Claviceps purpurea and Amanita muscaria by name, and confining himself to but a single paragraph on the 'flying ointment' on page 303 of 'Ecstasies...' :

In the Sabbath the judges more and more frequently saw the accounts of real, physical events. For a long time the only dissenting voices were those of the people who, referring back to the Canon episcopi, saw witches and sorcerers as the victims of demonic illusion. In the sixteenth century scientists like Cardano or Della Porta formulated a different opinion : animal metamorphoses, flights, apparitions of the devil were the effect of malnutrition or the use of hallucinogenic substances contained in vegetable concoctions or ointments...But no form of privation, no substance, no ecstatic technique can, by itself, cause the recurrence of such complex experiences...the deliberate use of psychotropic or hallucinogenic substances, while not explaining the ecstasies of the followers of the nocturnal goddess, the werewolf, and so on, would place them in a not exclusively mythical dimension.

– in short, a substrate of shamanic myth could, when catalysed by a drug experience (or simple starvation), give rise to a 'journey to the Sabbath', not of the body, but of the mind. Ergot and the Fly Agaric mushroom, while undoubtedly hallucinogenic,[18] were not among the ingredients listed in recipes for the flying ointment. The active ingredients in such unguents were primarily, not fungi, but plants in the nightshade family Solanaceae, most commonly Atropa belladonna (Deadly Nightshade) and Hyoscyamus niger (Henbane), belonging to the tropane alkaloid-rich tribe Hyoscyameae.[19] Other tropane-containing, nightshade ingredients included the famous Mandrake Mandragora officinarum, Scopolia carniolica and Datura stramonium, the Thornapple.[20] The alkaloids Atropine, Hyoscyamine and Scopolamine present in these Solanaceous plants are not only potent (and highly toxic) hallucinogens, but are also fat-soluble and capable of being absorbed through unbroken human skin.[21]

See also

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Witches' Sabbath. |

References

- ↑ Musgrave, James Brent & James Houran. (1999). "The Witches' Sabbat in Legend and Literature". Lore and Language.

- ↑ Wilby, Emma (Summer 2013). "Burchard's strigae, the Witches' Sabbath, and Shamanistic Cannibalism in Early Modern Europe" (PDF). Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Rosenthal, Carlo Ginzburg ; translated by Raymond (1991). Ecstasies deciphering the witches' Sabbath (1st American ed.). New York: Pantheon Books. ISBN 0394581636.

- ↑ On the Name of the Weekly Day of Rest (PDF).

- ↑ Mormando, Franco (1999). The preacher's demons : Bernardino of Siena and the social underworld of early Renaissance Italy. Chicago [u.a.]: Univ. of Chicago Press. ISBN 0226538540.

- ↑ Hutton, Ronald (3 July 2014). "The Wild Hunt and the Witches' Sabbath". Folklore. 125 (2): 161–178. doi:10.1080/0015587X.2014.896968.

- 1 2 3 Hendrix, Scott E. (December 2011). "The Pursuit of Witches and the Sexual Discourse of the Sabbat" (PDF). Anthropology. 11 (2): 41–58.

- ↑ Garrett, Julia M. (2013). "Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England". Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies. 13 (1): 34. doi:10.1353/jem.2013.0002. Retrieved 5 January 2017.

- ↑ Cohn, Norman (1975). Europe's inner demons : an enquiry inspired by the great witch-hunt. New York: Basic Books. ISBN 046502131X.

- ↑ Marnef, Guido (1997). "Between Religion and Magic: An Analysis of Witchcraft Trials in the Spanish Netherlands, Seventeenth Century". In Schäfer, Peter; Kippenberg, Hans Gerhard. Envisioning Magic: A Princeton Seminar and Symposium. Brill. pp. 235–54. ISBN 90-04-10777-0. p. 252

- ↑ Black, Christopher F. (2009). The Italian inquisition. New Haven: Yale University Press. ISBN 9780300117066.

- ↑ Kieckhefer, Richard (1976). European witch trials : their foundations in popular and learned culture, 1300–1500. London: Routledge & K. Paul. ISBN 0710083149.

- ↑ Peters, Edward (2001). "Sorcerer and Witch". In Jolly, Karen Louise; Raudvere, Catharina; et al. Witchcraft and Magic in Europe: The Middle Ages. Continuum International Publishing Group. pp. 233–37. ISBN 978-0-485-89003-7.

- ↑ Park, Robert E., "Review of Life in a Haitian Valley," American Journal of Sociology Vol. 43, No. 2 (Sep., 1937), pp. 346–348.

- ↑ Lewin, Louis Phantastica, Narcotic and Stimulating Drugs : Their Use and Abuse. Translated from the second German edition by P.H.A. Wirth, pub. New York : E.P. Dutton. Original German edition 1924.

- ↑ Harner, Michael J., Hallucinogens and Shamanism, pub. Oxford University Press 1973, reprinted U.S.A.1978 Chapter 8 : pps. 125–150 : The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft.

- ↑ Hansen, Harold A. The Witch's Garden pub. Unity Press 1978 ISBN 978-0913300473

- ↑ Schultes, Richard Evans; Hofmann, Albert (1979). The Botany and Chemistry of Hallucinogens (2nd ed.). Springfield Illinois: Charles C. Thomas. pps. 261-4.

- ↑ Hunziker, Armando T. The Genera of Solanaceae A.R.G. Gantner Verlag K.G., Ruggell, Liechtenstein 2001. ISBN 3-904144-77-4.

- ↑ Schultes, Richard Evans; Albert Hofmann (1979). Plants of the Gods: Origins of Hallucinogenic Use New York: McGraw-Hill. ISBN 0-07-056089-7.

- ↑ Sollmann, Torald, A Manual of Pharmacology and Its Applications to Therapeutics and Toxicology. 8th edition. Pub. W.B. Saunders, Philadelphia and London 1957.

Further reading

- Harner, Michael (1973). Hallucinogens and Shamanism. – See the chapter "The Role of Hallucinogenic Plants in European Witchcraft"

- Michelet, Jules (1862). Satanism and Witchcraft: The Classic Study of Medieval Superstition. ISBN 978-0-8065-0059-1. The first modern attempt to outline the details of the medieval Witches' Sabbath.

- Summers, Montague (1926). The History of Witchcraft. Chapter IV, The Sabbat has detailed description of Witches' Sabbath, with complete citations of sources.

- Robbins, Rossell Hope, ed. (1959). "Sabbat". The Encyclopedia of Witchcraft and Demonology. Crown. pp. 414–424. See also the extensive topic bibliography to the primary literature on pg. 560.

- Musgrave, James Brent and James Houran. (1999). "The Witches' Sabbat in Legend and Literature." Lore and Language 17, no. 1-2. pg 157–174.

- Wilby, Emma. (2013) "Burchard's Strigae, the Witches' Sabbath, and Shamnistic Cannibalism in Early Modern Europe." Magic, Ritual, and Witchcraft 8, no.1: 18–49.

- Sharpe, James. (2013) "In Search of the English Sabbat: Popular Conceptions of Witches' Meetings in Early Modern England. Journal of Early Modern Studies. 2: 161–183.

- Hutton, Ronald. (2014) "The Wild Hunt and the Witches' Sabbath." Folklore. 125, no. 2: 161–178.

- Roper, Lyndal. (2004) Witch Craze: Terror and Fantasy in Baroque Germany. -See Part II: Fantasy Chapter 5: Sabbaths

- Thompson, R.L. (1929) The History of the Devil- The Horned God of the West- Magic and Worship.

- Murray, Margaret A. (1962)The Witch-Cult in Western Europe. (Oxford: Clarendon Press)

- Black, Christopher F. (2009) The Italian Inquisition. (New Haven: Yale University Press). See Chapter 9- The World of Witchcraft, Superstition and Magic

- Ankarloo, Bengt and Gustav Henningsen. (1990) Early Modern European Witchcraft: Centres and Peripheries (Oxford: Clarendon Press). see the following essays- pg 121 Ginzburg, Carlo "Deciphering the Sabbath," pg 139 Muchembled, Robert "Satanic Myths and Cultural Reality," pg 161 Rowland, Robert. "Fantastically and Devilishe Person's: European Witch-Beliefs in Comparative Perspective," pg 191 Henningsen, Gustav "'The Ladies from outside': An Archaic Pattern of Witches' Sabbath."

- Wilby, Emma. (2005) Cunning Folk and Familiar Spirits: Shamanistic visionary traditions in Early Modern British Witchcraft and Magic. (Brighton: Sussex Academic Press)

- Garrett, Julia M. (2013) "Witchcraft and Sexual Knowledge in Early Modern England," Journal for Early Modern Cultural Studies 13, no. 1. pg 32–72.

- Roper, Lyndal. (2006) "Witchcraft and the Western Imagination," Transactions of the Royal Historical Society 6, no. 16. pg 117–141.