Datura stramonium

| Jimsonweed | |

|---|---|

.jpg) | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Plantae |

| Clade: | Angiosperms |

| Clade: | Eudicots |

| Clade: | Asterids |

| Order: | Solanales |

| Family: | Solanaceae |

| Genus: | Datura |

| Species: | D. stramonium |

| Binomial name | |

| Datura stramonium | |

| Synonyms[1] | |

|

Synonymy

| |

Datura stramonium, known by the English names jimsonweed or devil's snare, is a plant in the nightshade family. It is believed to have originated in Mexico,[2] but has now become naturalized in many other regions.[3][4][5] Other common names for D. stramonium include thornapple and moon flower,[6] and it has the Spanish name toloache.[7] Other names for the plant include hell's bells, devil's trumpet, devil's weed, tolguacha, Jamestown weed, stinkweed, locoweed, pricklyburr, false castor oil plant,[8] devil's cucumber,[9] and thornapple.[10]

Datura has been used in traditional medicine to relieve asthma symptoms and as an analgesic during surgery or bonesetting. It is also a powerful hallucinogen and deliriant, which is used entheogenically for the intense visions it produces. However, the tropane alkaloids responsible for both the medicinal and hallucinogenic properties are fatally toxic in only slightly higher amounts than the medicinal dosage, and careless use often results in hospitalizations and deaths.

Description

Datura stramonium is a foul-smelling, erect, annual, freely branching herb that forms a bush up to 60 to 150 cm (2 to 5 ft) tall.[11][12][13]

The root is long, thick, fibrous, and white. The stem is stout, erect, leafy, smooth, and pale yellow-green to reddish purple in color. The stem forks off repeatedly into branches, and each fork forms a leaf and a single, erect flower.[13]

The leaves are about 8 to 20 cm (3–8 in) long, smooth, toothed,[12] soft, and irregularly undulated.[13] The upper surface of the leaves is a darker green, and the bottom is a light green.[12] The leaves have a bitter and nauseating taste, which is imparted to extracts of the herb, and remains even after the leaves have been dried.[14]

Datura stramonium generally flowers throughout the summer. The fragrant flowers are trumpet-shaped, white to creamy or violet, and 6 to 9 cm (2 1⁄2–3 1⁄2 in) long, and grow on short stems from either the axils of the leaves or the places where the branches fork. The calyx is long and tubular, swollen at the bottom, and sharply angled, surmounted by five sharp teeth. The corolla, which is folded and only partially open, is white, funnel-shaped, and has prominent ribs. The flowers open at night, emitting a pleasant fragrance, and are fed upon by nocturnal moths.[13]

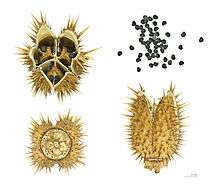

The egg-shaped seed capsule is 3 to 8 cm (1–3 in) in diameter and either covered with spines or bald. At maturity, it splits into four chambers, each with dozens of small, black seeds.[13]

Range and habitat

Datura stramonium is native to North America, but was spread to the Old World early. It was scientifically described and named by Swedish botanist Carl Linnaeus in 1753, although it had been described a century earlier by botanists such as Nicholas Culpeper.[15] Today, it grows wild in all the world's warm and moderate regions, where it is found along roadsides and at dung-rich livestock enclosures.[16][17][18] In Europe, it is found as a weed on wastelands and in garbage dumps.[16]

The seed is thought to be carried by birds and spread in their droppings. Its seeds can lie dormant underground for years and germinate when the soil is disturbed. The Royal Horticultural Society has advised worried gardeners to dig it up or have it otherwise removed,[19] while wearing gloves to handle it.[20]

Toxicity

All parts of Datura plants contain dangerous levels of the tropane alkaloids atropine, hyoscyamine, and scopolamine, which are classified as deliriants, or anticholinergics. The risk of fatal overdose is high among uninformed users, and many hospitalizations occur amongst recreational users who ingest the plant for its psychoactive effects.[16][21]

The amount of toxins varies widely from plant to plant. As much as a 5:1 variation can be found between plants, and a given plant's toxicity depends on its age, where it is growing, and the local weather conditions.[16] Additionally, within a given datura plant, toxin concentration varies by part and even from leaf to leaf. When the plant is younger, the ratio of scopolamine to atropine is about 3:1; after flowering, this ratio is reversed, with the amount of scopolamine continuing to decrease as the plant gets older.[22] In traditional cultures, a great deal of experience with and detailed knowledge of Datura was critical to minimize harm.[16] An individual datura seed contains about 0.1 mg of atropine, and the approximate fatal dose for adult humans is >10 mg atropine or >2–4 mg scopolamine.[23]

Datura intoxication typically produces delirium, hallucination, hyperthermia, tachycardia, bizarre behavior, and severe mydriasis with resultant painful photophobia that can last several days. Pronounced amnesia is another commonly reported effect.[24] The onset of symptoms generally occurs around 30 to 60 minutes after ingesting the herb. These symptoms generally last from 24 to 48 hours, but have been reported in some cases to last as long as two weeks.[25]

As with other cases of anticholinergic poisoning, intravenous physostigmine can be administered in severe cases as an antidote.[26]

Use

Traditional medicine

In Ayurveda, datura has long been used for asthma symptoms. The active agent is atropine. The leaves are generally smoked either in a cigarette or a pipe. During the late 18th century, James Anderson, the English Physician General of the East India Company, learned of the practice and popularized it in Europe.[27][28]

The Zuni people once used datura as an analgesic to render patients unconscious while broken bones were set.[29] The Chinese also used it as a form of anesthesia during surgery.[30]

Early European medicine

John Gerard's Herball (1597) states,

[T]he juice of Thornapple, boiled with hog's grease, cureth all inflammations whatsoever, all manner of burnings and scaldings, as well of fire, water, boiling lead, gunpowder, as that which comes by lightning and that in very short time, as myself have found in daily practice, to my great credit and profit.[31]

William Lewis reported in the late 18th century that the juice could be made into "a very powerful remedy in various convulsive and spasmodic disorders, epilepsy and mania," and was also "found to give ease in external inflammations and haemorrhoids."[32]

Spiritual uses

The ancient inhabitants of what is today central and southern California used to ingest the small black seeds of datura to "commune with deities through visions".[33] Across the Americas, other indigenous peoples such as the Algonquin, Navajo, Cherokee, Luiseño and the indigenous peoples of Marie-Galante also used this plant in sacred ceremonies for its hallucinogenic properties.[34][35][36] In Ethiopia, some students and debtrawoch (lay priests), use D. stramonium to "open the mind" to be more receptive to learning, and creative and imaginative thinking.[37]

In his book, The Serpent and the Rainbow, Wade Davis identified D. stramonium, called "zombi cucumber" in Haiti, as a central ingredient of the concoction vodou priests use to create zombies.[38][39]

The common name "datura" has its origins in India, where the sister species Datura metel is considered particularly sacred — believed to be a favorite of Shiva in Shaivism.[40]

Cultivation

Datura prefers rich, calcareous soil. Adding nitrogen fertilizer to the soil will increase the concentration of alkaloids present in the plant. Datura can be grown from seed, which is sown with several feet between plants. Datura is sensitive to frost, so should be sheltered during cold weather. The plant is harvested when the fruits are ripe, but still green. To harvest, the entire plant is cut down, the leaves are stripped from the plant, and everything is left to dry. When the fruits begin to burst open, the seeds are harvested. For intensive plantations, leaf yields of and seed yields of are possible.[41]

Etymology

The genus name is derived from the plant's Hindi name धतूरा dhatūra, ultimately from Sanskrit धत्तूर 'white thorn-apple'.[42] Stramonium is originally from Greek "nightshade" and "mad".[43]

In the United States, the plant is called "jimsonweed", or more rarely "Jamestown weed"; it got this name from the town of Jamestown, Virginia, where British soldiers consumed it while attempting to suppress Bacon's Rebellion. They spent 11 days in altered mental states:

Fossil record

Fossil seeds like seeds of Datura stramonium have been found in Pliocene strata of Belarus.[44]

External links

- USDA Natural Resources Conservation Service PLANTS Profile: Datura stramonium L.

- Datura stramonium at Liber Herbarum II

- Datura spp. at Erowid

- Datura stramonium Pictures and information

- ↑ The Plant List, Datura stramonium L.

- ↑ "Datura stramonium in Flora of China @ efloras.org". www.efloras.org. Retrieved 2017-08-16.

- ↑ "Datura stramonium". Germplasm Resources Information Network (GRIN). Agricultural Research Service (ARS), United States Department of Agriculture (USDA). Retrieved 2008-02-05.

- ↑ "Biota of North America Program, 2014 county distribution map". bonap.net.

- ↑ Australia, Atlas of Living. "Datura stramonium : Common thornapple | Atlas of Living Australia". bie.ala.org.au. Retrieved 2017-08-16.

- ↑ "Jimsonweed". University of Texas El Paso / Austin Cooperative Pharmacy Program & Paso del Norte Health Foundation. Archived from the original on 29 July 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ "Detailed Information: Jimsonweed". University of Texas El Paso / Austin Cooperative Pharmacy Program & Paso del Norte Health Foundation. Archived from the original on 15 April 2013. Retrieved 2013-02-13.

- ↑ Joseph Henry Maiden (1920). The Weeds of New South Wales. 1. W.A. Gullick, Government printer. p. 76.

Thorn Apple or False Castor Oil Plant)

- ↑ "Thorn-apple, Datura stramonium – Flowers – NatureGate". luontoportti.com.

- ↑ Bunney, Sarah. Illustrated Encyclopedia of Herbs.

- ↑ Stace, Clive (1997). New Flora of the British Isles. Cambridge University Press. p. 532. ISBN 0-521-65315-0.

- 1 2 3 Henkel, Alice (1911). "Jimson weed". American Medicinal Leaves and Herbs. U.S. Government Printing Office. p. 30.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 2. Dover Publications. p. 804. ISBN 978-0-486-22799-3.

- ↑ Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 2. Dover Publications. p. 805. ISBN 978-0-486-22799-3.

- ↑ Culpeper, Nicholas (1653), Culpeper's Complete Herbal, Slough: W Foulsham & Co Ltd, pp. 368–369, ISBN 0-572-00203-3

- 1 2 3 4 5 Preissel, Ulrike & Hans-Georg Preissel (2002). Brugmansia and Datura: Angel's Trumpets and Thorn Apples. Firefly Books. pp. 124–125. ISBN 1-55209-598-3.

- ↑ Veblen, K.E. (2012). "Savanna glade hotspots: Plant community development and synergy with large herbivores". Journal of Arid Environments. 78: 119–127. doi:10.1016/j.jaridenv.2011.10.016.

- ↑ Oudhia P., Tripathi R.S.(1998).Allelopathic potential of Datura stramonium L.. Crop. Res. 16 (1) : 37-40.

- ↑ "Deadly Harry Potter plant devil's snare turns up in Suffolk pensioner's garden". Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ↑ "There's a devil in my garden..." Dawlish Newspapers. Retrieved 2017-08-30.

- ↑ AJ Giannini,Drugs of Abuse--Second Edition. Los Angeles, Practice Management Information Corporation, pp.48-51. ISBN 1-57066-053-0.

- ↑ Nellis, David W. (1997). Poisonous Plants and Animals of Florida and the Caribbean. Pineapple Press. p. 237. ISBN 978-1-56164-111-6.

- ↑ Arnett AM (December 1995). "Jimson Weed (Datura stramonium) poisoning". Clinical Toxicology Review. 18 (3).

- ↑ Freye, Enno (21 September 2009). Pharmacology and Abuse of Cocaine, Amphetamines, Ecstasy and Related Designer Drugs. Springer Netherlands. pp. 217–218. ISBN 978-90-481-2447-3.

- ↑ Pennachio, Marcello et al. (2010). Uses and Abuses of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Ethnobotany As Hallucinogen, Perfume, Incense, and Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 7. ISBN 978-0-19-537001-0.

- ↑ Goldfrank, Lewis R.; Flommenbaum, Neil (2006). Goldfrank's Toxicologic Emergencies. McGraw-Hill Professional. p. 677. ISBN 978-0-07-147914-1.

- ↑ Barceloux, Donald G. (2008). "Cascara". Medical Toxicology of Natural Substances: Foods, Fungi, Medicinal Herbs, Plants, and Venomous Animals. John Wiley & Sons. p. 1877. ISBN 978-1-118-38276-9.

- ↑ Pennachio, Marcello et al. (2010). Uses and Abuses of Plant-Derived Smoke: Its Ethnobotany As Hallucinogen, Perfume, Incense, and Medicine. Oxford University Press. p. 6. ISBN 978-0-19-537001-0.

- ↑ Turner, Matt W. (2009). Remarkable Plants of Texas: Uncommon Accounts of Our Common Natives. University of Texas Press. p. 209. ISBN 978-0-292-71851-7.

- ↑ Nellis, David W. (1997). Poisonous Plants and Animals of Florida and the Caribbean. Pineapple Press. p. 238. ISBN 978-1-56164-111-6.

- ↑ Grieve, Maud (1971). A Modern Herbal: The Medicinal, Culinary, Cosmetic and Economic Properties, Cultivation and Folk-lore of Herbs, Grasses, Fungi, Shrubs, & Trees with All Their Modern Scientific Uses, Volume 2.

- ↑ William Lewis, "An Experimental History Of The Materia Medica: Stramonium"

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ Clairvius Narcisse

- ↑ Davis, Wade (1985), The Serpent and the Rainbow, New York: Simon & Schuster

- ↑ name="Pennachio-2010-p6"

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑

- ↑ The Pliocene flora of Kholmech, south-eastern Belarus and it's correlation with other Pliocene floras of Europe by Felix Yu. VELICHKEVICH and Ewa ZASTAWNIAK – Acta Palaeobot. 43(2): 137–259, 2003