Talisman

A talisman is an object that someone believes holds magical properties that bring good luck to the possessor or protect the possessor from evil or harm.[1]

According to the Hermetic Order of the Golden Dawn, a magical order active in the United Kingdom during the late 19th and early 20th century, a talisman is "a magical figure charged with the force which it is intended to represent." The Order also cautions that one must take great care in creating a talisman and ensure that the physical item's symbolism closely represents the intended purpose of the talisman. The Order notes that the forces depicted by the item "should be in exact harmony with those you wish to attract, and the more exact the symbolism, the easier it is to attract the force."[2]

Etymology

The word talisman comes from French talisman, via Arabic tilsam (طلسم, plural tilsaman), which comes from the ancient Greek telesma (τέλεσμα), meaning "completion, religious rite, payment",[3][4] ultimately from the verb teleō (τελέω), "I complete, perform a rite".[5]

Preparation of talismans

Traditional magical schools advise that a talisman should be created by the person who plans to use it. It is also said that the person who makes the talisman must be well-versed in the symbolism of elemental and planetary forces. For example several known medieval talismans featured geomantic signs and symbols in relation to planets symbols, which are also frequently used in geomantic divination and Alchemy.

Other features with magical associations—such as colors, scents, symbology, patterns, and Kabbalistic figures—can be integrated into the creation of a talisman in addition to the chosen planetary or elemental symbolism. However, these must be used in harmony with the elemental or planetary force chosen so as to amplify the intended power of the talisman. It is also possible to add a personal touch to the talisman by incorporating a verse, inscription, or pattern that is of particular meaning to the maker. These inscriptions can be sigils (magical emblems), bible verses, or sonnets, but they too must be in harmony with the talisman's original purpose.[2]

Use of talismans in medieval medicine

Lea Olsan writes of the use of amulets and talismans as prescribed by medical practitioners in the medieval period. She notes that the use of such charms and prayers was "rarely a treatment of choice" [6] because such treatments could not be properly justified in the realm of Galen medical teachings. Their use, however, was typically considered acceptable; references to amulets were common in medieval medical literature.

For example, one well-known medieval physician, Gilbertus, writes of the necessity of using a talisman to ensure conception of a child. He describes the process of producing this kind of talisman as "...writing words, some uninterruptible, some biblical, on a parchment to be hung around the neck of the man or woman during intercourse."[6]

Examples

Zulfiqar

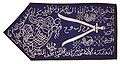

Zulfiqar, the magical sword of Ali, was frequently depicted on Ottoman flags, especially as used by the Janissary cavalry, in the 16th and 17th centuries.

This version of the complete prayer of Zulfiqar is also frequently invoked in talismans of the Qizilbash warriors:

| شاه مردان،

شیر یزدان، قدرت خدا، لا فتى إلا علي، لا سيف إلا ذو الفقار، |

''Shah-e-Mardan,

Sher-e-Yazdan, Quwat-e-Khuda, Lafata illah Ali; La Saif Illh Zulfiqar.'' |

"Leader of men-at-arms, The lion of Yazdan (a name of God in Persian language ) , Might by the most high (God), There is none like Ali; No sword like Zulfiqar. |

|---|

A record of Live like Ali, die like Hussein as part of a longer talismanic inscription was published by Tewfik Canaan in The Decipherment of Persian and sometimes Arabic Talismans (1938).[7]

The Emperor of Mughal Shah Jahan leading the Mughal Army. In the upper left, war elephants bear emblems of the legendary Zulfiqar.

The Emperor of Mughal Shah Jahan leading the Mughal Army. In the upper left, war elephants bear emblems of the legendary Zulfiqar. A flag from Cirebon with the Zulfiqar and Ali represented as a lion (dated to the late 18th or the 19th century).

A flag from Cirebon with the Zulfiqar and Ali represented as a lion (dated to the late 18th or the 19th century). An early 19th century flag of Ottoman Zulfiqar.

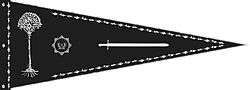

An early 19th century flag of Ottoman Zulfiqar. A representation of the sword of Ali (Zulfiqar), in the flag of Ahmad Shah Durrani.

A representation of the sword of Ali (Zulfiqar), in the flag of Ahmad Shah Durrani.

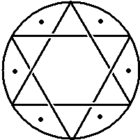

Seal of Solomon

The Seal of Solomon, also known as the interlaced triangle, is another ancient talisman and amulet that has been commonly used in several religions. Reputed to be the emblem by which King Solomon ruled the Genii, it could not have originated with him. Its use has been traced in different cultures long before the Jewish Dispensation. As a talisman it was believed to be all-powerful, the ideal symbol of the absolute, and was worn for protection against all fatalities, threats, and trouble, and to protect its wearer from all evil. In its constitution, the triangle with its apex upwards represents good, and with the inverted triangle, evil.

The triangle with its apex up was typical of the Trinity, figures that occur in several religions. In India, China and Japan, its three angles represent Brahma, Vishnu, and Shiva, the Creator, Preserver, and Destroyer or Re-generator. In ancient Egypt, it represented the deities Osiris, Isis and Horus. In Christianity, it represented the Holy Trinity. As a whole it stands for the elements of fire and spirit, composed of the three virtues (love, truth, and wisdom). The triangle with its apex downward symbolized the element of water, and typified the material world, or the three enemies of the soul: the world, the flesh, and the Devil, and the cardinal sins, envy, hatred and malice. Therefore, the two triangles interlaced represent the victory of spirit over matter. The early cultures that contributed to Western civilization believed that the Seal of Solomon was an all-powerful talisman and amulet, especially when used with either a Cross of Tau, the Hebrew Yodh, or the Egyptian Crux Ansata in the center.[8]:19–20

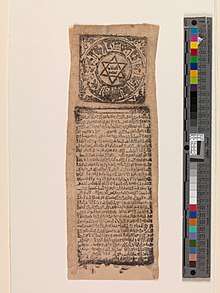

Talismanic Scroll

This object, a Talismanic Scroll dating from the 11th-century was discovered in Egypt and produced in the Fatimid Islamic Caliphate (909-1171 C.E.). It resides in the collection of the Metropolitan Museum of Art (New York, NY)[9] along with a number of other Medieval Islamic amulets and talismans that were donated to the museum by the Abemayor family in 1978. About 9 inches by 3 inches in size, the miniature paper scroll contains a combination of prayers and Quranic verses, and was created for placement in an amulet box. This block print bears Kufic, the oldest calligraphic Arabic script, as well as Solomon's Seal, a star with six points that has been identified in a large number of Islamic art pieces of the period. Block printing was utilized as a technique through which to mass-produce talisman scrolls, hundreds of years before block printing was incorporated into European societies.[10]

Swastika

The swastika, one of the oldest and most widespread talismans known, can be traced to the Stone Age, and has been found incised on stone implements of this era. It can be found in all parts of the Old and New Worlds, and on the most prehistoric ruins and remnants. In spite of the assertion by some writers that it was used by the Egyptians, there is little evidence to suggest they used it and it has not been found among their remains.

Both forms, with arms turned to the left and to the right, seem equally common. On the stone walls of the Buddhist caves of India, which feature many of the symbols, arms are often turned both ways in the same inscription.[8]:15

Uraniborg

The Renaissance scientific building Uraniborg has been interpreted as an astrological talisman to support the work and health of scholars working inside it, designed using Marsilio Ficino's theorized mechanism for astrological influence. Length ratios that the designer, the astrologer and alchemist Tycho Brahe, worked into the building and its gardens match those that Heinrich Cornelius Agrippa associated with Jupiter and the sun. This choice would have counteracted the believed tendency of scholars to be phlegmatic, melancholy and overly influenced by the planet Saturn.[11]

References

- ↑ Campo, Juan E. (2009). Encyclopedia of Islam. New York: Facts On File. p. 40. ISBN 1438126964.

- 1 2 Gonzalez-Wippler, Migene (2001). Complete Book Of Amulets & Talismans. Lewellyn Publications. ISBN 0-87542-287-X.

- ↑ "talisman - Definition of talisman in English by Oxford Dictionaries". Oxford Dictionaries - English. Retrieved 17 March 2018.

- ↑ "Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, τέλεσμα". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 18 March 2018.

- ↑ "Henry George Liddell, Robert Scott, A Greek-English Lexicon, τελέω". Perseus.tufts.edu. Retrieved 19 April 2017.

- 1 2 Olsan, L. T. (1 December 2003). "Charms and Prayers in Medieval Medical Theory and Practice". Social History of Medicine. 16 (3): 343–366. doi:10.1093/shm/16.3.343.

- ↑ Savage-Smith, Emilie (2004). Magic and Divination in Early Islam. Ashgate Publishing. pp. 125–177. ISBN 9780860787150.

- 1 2 Thomas, William; Pavitt, Kate (1995). The Book of Talismans, Amulets and Zodiacal Gems. Kila, Montana: Kessinger Publishing Company. ISBN 9781564594617.

- ↑ "Talismanic Scroll". The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved 2013-08-23.

- ↑ "Talismanic Scroll | The Met". Metmuseum.org. Retrieved 2017-04-19.

- ↑ Kwan, Alistair (1 March 2011). "Tycho's Talisman: Astrological Magic in the Design of Uraniborg". Early Science and Medicine. 16 (2): 95–119. doi:10.1163/157338211X557075.

External links

| Wikisource has the text of the 1905 New International Encyclopedia article Talisman. |

- Forshaw, Peter (2015) 'Magical Material & Material Survivals: Amulets, Talismans, and Mirrors in Early Modern Europe’, in Dietrich Boschung and Jan N. Bremmer (eds), The Materiality of Magic. Wilhelm Fink.