White Serbia

White Serbia, called also Boiki, is the mythical homeland of the White Serbs (see Sorbs) from whom the medieval Serbs originate. While White Serbia is not explicitly mentioned, Boiki is mentioned in De Administrando Imperio, a 10th-century work by Byzantine Emperor Constantine VII (r. 913–959). According to it the "White Serbs" lived on the "other side of Turkey" (i.e. Hungary), in the area that they called "Boiki". The area adjacent to it was known as White Croatia, where the White Croats trace their origin.

Location

Sources

Constantine VII in De Administrando Imperio recounts in 32nd chapter "It should be known that the Serbs are descended from the unbaptized Serbs, also called ‘white’, who live beyond Turkey, in a region called by them Boïki, where their neighbor is Francia, as is also Megali Croatia, the unbaptized, also called ‘white’. In this place, then, these Serbs also dwelt from the beginning... Now, after the two brothers succeeded their father in the rule of Serbia, one of them, taking one half of the folk, came as the refugee to Heraclius, the emperor of the Romaioi... Then, after some time these same Serbs decided to depart to their own homes, and the emperor sent them off. And so, when they had crossed the Danube River, they changed their minds and sent a request to the Emperor Heraclius... the emperor settled these same Serbs in these countries", while in 33rd chapter a subchapter recounts "(It should be known) that the clan of the anthypatos and patrikios Michael, son of Visevitz, archon of the Zachlumians, came from the unbaptized inhabitants on the Visla River, called Litziki, and they settled on the river called Zachluma".[1][2] A Latin document from the early 10th century recorded that the "Hungarians moved to Pannonia from Serbia (Ungarorum gens a Servia egressa in Pannoniam)", which is referring most probably to same White Serbia.[3]

Dispute

Theories on the location of White Serbia and Serbs have been disputed. P. J. Šafárik (1795–1865) classified the White Serbs as a Polabian Slavonic tribe.[4][5] B. Kállay (1839–1903) noted that many historians assumed that White Serbia was identical to the Czech lands (Bohemia), or that the Czech lands were part of White Serbia, based on DAI's account and the name Bojka.[6] He however believed that Šafařík's theory was more likely; that White Serbia was north of the Carpathians, stretching over western Russia and eastern Poland.[6] B. Drobnjaković (1890–1961) noted that Bojka reminded of Bohemia.[7], similar opinion was shared by A. Stratos (1905–1981),[8] and S. Ćirković (1929–2009) who considered it to be between the Elbe and Saale rivers.[9] R. Novaković (1911–2003) connected the name to Bohemia (in turn derived from Celtic Boii) and located it in Polabia.[10] V. Ćorović (1885–1941) believed White Serbia included Galicia and the area around the sources of Dniester and Vistula.[11] L. Cerović (b. 1936) connected it to the land of the Boykos, Bojkovina, in the northern Carpathians.[12] F. Conte (b. 1944) believed it to be in the area of Poland.[13] J. Kovaćević noted the toponym Beloserbye in a 1393 document, situated in Poland between Czarnków and Żnin.[14]

According to V. V. Sedov, the 32nd chapter of De Administrando Imperio indicates it was located in the Lower Lusatia territory where were located the Sorbs,[15] but the 33rd chapter about Zachlumia caused confusion which resulted with several hypotheses.[16] The first group of scholars argued the homeland existed between rivers Elbe and Saale, the second in the upper course of rivers Vistula and Oder, and the third from Elbe and Saale to the upper course of Vistula.[16] However, Sedov concluded that the archaeological data does not confirm any of these hypotheses, and most plausible is the consideration by Lubor Niederle that there's no evidence that White Serbia ever existed and Constantine VII most probably made up Northern Great Serbia only according to the analogy with Great Croatia.[16] According to Tibor Živković, the structure and content of the subchapter about the family of Michael of Zahumlje indicate they were most probably told by the Michael himself, and notably is not mentioned Serbian origin. Živković considered that it was possible his ruling family preserved the memory of their tribal origin, which is further evidence about the Northern origin of both the Serbs and Croats, to be roughly genuine stories, and not part of a political context.[17]

Gallery

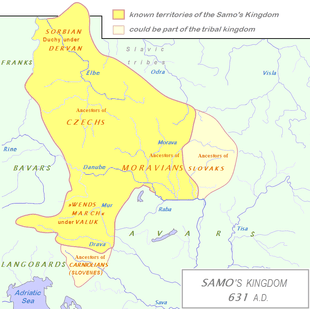

Dervan's polity in the 7th century.

Dervan's polity in the 7th century. Samo's realm in 631, including Dervan's polity.

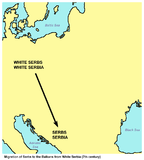

Samo's realm in 631, including Dervan's polity. White Serbia and White Croatia (around 560), according to Francis Dvornik.

White Serbia and White Croatia (around 560), according to Francis Dvornik. Lusatian (Sorb) theory.

Lusatian (Sorb) theory. Lusatian (Sorb) theory, including Proto-Slav lands.

Lusatian (Sorb) theory, including Proto-Slav lands.

See also

References

- ↑ Živković 2012, p. 152–185.

- ↑ Sedov 2013, p. 458–459.

- ↑ Živković 2012, p. 153.

- ↑ H.H. Howorth Esq. FSA The Spread of Slaves Part III, P 181 "They are classed together by Schafarik under the name of Polabian Slaves"

- ↑

- 1 2 Béni Kállay (1882). Istorija srpskoga naroda. Petar Curčić. p. 14.

- ↑ Borivoje M. Drobnjaković (1960). Etnologija naroda Jugoslavije. 1 (1960). Naučna knjiga. p. 102.

- ↑ Andreas Nikolaou Stratos (1968). Byzantium in the seventh century. Adolf M. Hakkert.

- ↑ Ćirković 2004, p. 17.

- ↑ Vizantološki institut (1996). Recueil de travaux de l'Institut des études byzantines. 35. Vizantološki institut SANU. p. 127.

- ↑ Ćorović 2001, ch. Словени насељавају Балкан.

- ↑ Ljubivoje Cerović (2002). Srbi u Ukrajini. Muzej Vojvodine. p. 13.

- ↑ Francis Conte (1995). The Slavs. East European Monographs. p. 28. ISBN 978-0-88033-310-8.

- ↑ Zbornik radova Vizantološkog instituta. 38. Institut. 2000. p. 91.

- ↑ Sedov 2013, p. 458.

- 1 2 3 Sedov 2013, p. 459.

- ↑ Živković 2012, p. 185.

Sources

- Constantine VII Porphyrogenitus (1993). De Administrando Imperio (Moravcsik, Gyula ed.). Washington D.C.: Dumbarton Oaks Center for Byzantine Studies.

- Einhard. Annales regni Francorum [Royal Frankish Annals] (in Latin).

- Ćorović, Vladimir (2001). Istorija srpskog naroda (Internet ed.). Belgrade: Ars Libri.

- Fine, John Van Antwerp (1991). The Early Medieval Balkans: A Critical Survey from the Sixth to the Late Twelfth Century. Michigan: The University of Michigan Press. ISBN 0-472-08149-7.

- Ferjančić, Božidar (1959). Vizantiski izvori za istoriju naroda Jugoslavije. 2. Vizantološki institut SANU. pp. 5, 47.

- Летопис Матице српске. 141–144. У Српској народној задружној штампарији. 1885. p. 145.

- Viktor Novak (1973). Istoriski časopis. 20. Prosveta. p. 7.

- The South Slav Journal. 22–23. Dositey Obradovich Circle. 2001. p. 149.

- Zbigniew Gołąb (1992). The origins of the Slavs: a linguist's view. Slavica Publishers, Inc. p. 397. ISBN 978-0-89357-224-2.

- Ćirković, Sima (2004). The Serbs. Malden: Blackwell Publishing.

- Živković, Tibor (2012), De Conversione Croatorum et Serborum: A Lost Source, Belgrade: Institute of History, ISBN 978-86-7743-096-2

- Sedov, Valentin Vasilyevich (2013) [1995]. Славяне в раннем Средневековье [Sloveni u ranom srednjem veku (Slavs in Early Middle Ages)]. Novi Sad: Akademska knjiga. ISBN 978-86-6263-026-1.

Further reading

- Sakač, Simeon (1994). "Бојки — прапостојбина Срба на Карпатима". Рад музеја Војводине. 36: 145–149. (in Serbian)

- Novaković, Relja (1977). Odakle su Srbi došli na Balkansko poluostrvo. Istorijski institut. (in Serbian)

- Županić, Niko (1922). "Bela Srbija". Narodna starina. Zagreb. 2: 107–118. (in Croatian)