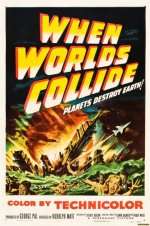

When Worlds Collide (1951 film)

| When Worlds Collide | |

|---|---|

| |

| Directed by | Rudolph Maté |

| Produced by | George Pal |

| Written by | Sydney Boehm |

| Based on |

the novel When Worlds Collide by Edwin Balmer and Philip Wylie |

| Starring |

Richard Derr Barbara Rush Peter Hansen John Hoyt |

| Music by | Leith Stevens |

| Cinematography |

W. Howard Greene John F. Seitz |

| Edited by | Arthur P. Schmidt |

Production company |

Paramount Pictures Corp. |

| Distributed by | Paramount Pictures Corp. |

Release date |

|

Running time | 83 minutes |

| Country | United States |

| Language | English |

| Budget | $936,000 (estimated) |

| Box office | $1.6 million (US rentals)[2] |

When Worlds Collide! is a 1951 American Technicolor science fiction film from Paramount Pictures, produced by George Pal, directed by Rudolph Maté, that stars Richard Derr, Barbara Rush, Peter Hansen, and John Hoyt. The film is based on the 1932 science fiction novel of the same name, co-written by Philip Wylie and Edwin Balmer.[3]

The plot concerns the coming destruction of the Earth by a rogue star[Note 1] called Bellus and the desperate efforts to build a space ark to transport a group of men and women to Bellus' single planet, Zyra.

Plot

The pilot David Randall flies top-secret photographs from the South African astronomer Dr. Emery Bronson to Dr. Cole Hendron in America. Hendron, with the assistance of his daughter Joyce Hendron, confirms their worst fears: Bronson has discovered that a rogue star named Bellus is on a collision course with Earth.

Hendron warns the United Nations that the end of the world is little more than eight months away. He pleads for the construction of "arks" (spaceships) to transport a lucky few to Zyra, the sole planet orbiting Bellus, in the faint hope that the human race can be saved from extinction. Other scientists scoff at his claims, and he receives no support from the delegates to the United Nations.

Hendron receives help from wealthy humanitarians, who arrange for a lease on a former proving ground to build an ark. To finance the construction, Hendron is forced to accept money from the wheelchair-bound business magnate Sidney Stanton. Stanton demands the right to select the passengers, but Hendron insists that he is not qualified to make those choices; all he can buy is a seat aboard the ark.

Joyce, attracted to Randall, persuades her father into keeping him around, much to the annoyance of her boyfriend, Dr. Tony Drake. As Bellus nears, former skeptics admit that Hendron was right and governments prepare for the inevitable. Groups in other nations begin to build their own spaceships. Martial law is declared, and residents in coastal regions are evacuated to inland cities.

Zyra makes a close approach first, causing massive earthquakes, volcanic eruptions, and tidal waves that wreak havoc around the world. Several people are killed at the ark's construction camp, including Dr. Bronson. Afterward, Drake and Randall travel by helicopter to drop off supplies to people in the surrounding area. When Randall gets off to rescue a little boy stranded on a roof in a flooded area, Drake flies away, but then he changes his mind and returns.

As the day of doom approaches, the spaceship is loaded with food, medicine, microfilmed copies of books, equipment, and animals. The lucky passengers are selected by lottery, though Hendron reserves seats for himself, Stanton, Joyce, Drake, pilot Dr. George Frey, the young boy who was rescued, and Randall, for his daughter's sake. When a young man turns in his winning number because his sweetheart was not selected, Hendron arranges for both to go. Randall only pretends to participate in the lottery, believing he has no skills needed for settling on Zyra. For Joyce's sake, Drake fabricates a "heart condition" for Frey, making Randall's inclusion as co-pilot seem necessary.

The cynical Stanton, knowing human nature, fears what the desperate lottery losers might do, so as a precaution, he has stockpiled weapons; Stanton's suspicions prove to be well-founded. His much-abused assistant, Ferris, tries to add himself at gunpoint to the passenger manifest, only to be shot dead by Stanton. As a precaution, the selected women board the ship, while the chosen men wait just outside.

Shortly before blastoff, many of the lottery losers riot, taking up Stanton's weapons to try to force their way aboard. Hendron stays behind at the last moment and forcibly keeps Stanton with him to conserve fuel. With an effort born of ultimate desperation, Stanton stands up and walks in a futile attempt to board the departing spaceship.

The crew are rendered unconscious by the g-force of acceleration and do not see on the monitor the Earth's destruction by Bellus. When Randall comes to and sees Dr. Frey already awake and piloting the ship, he realizes he has been deceived.

As the space ark enters Zyra's atmosphere, the fuel runs out; Randall takes control and glides the spaceship to a rough but safe landing. The crew disembark and find Zyra to be habitable. David Randall and Joyce Hendron walk hand-in-hand down the ramp as a new day dawns over their world. Artificial structures are visible in the distance to the left and right as they leave the ark, suggesting an alien civilization.

Cast

- Richard Derr as David Randall

- Larry Keating as Dr. Cole Hendron

- Barbara Rush as Joyce Hendron

- John Hoyt as Sydney Stanton

- Peter Hansen as Dr. Tony Drake

- Alden Chase as Dr. George Frey

- Hayden Rorke as Dr. Emery Bronson

- Frank Cady as Harold Ferris

Production

A feature film, based on the original novels When Worlds Collide and its sequel After Worlds Collide, first serialized in Blue Book magazine in 1932, was considered by producer-director Cecil B. DeMille. When George Pal began his version years later, he initially wanted a more lavish production with a larger budget, but he wound up being forced to scale back his plans.[4]

Douglas Fairbanks Jr. was first considered for the role of Dave Randall, but Richard Derr was finally hired for the part.[5]

Chesley Bonestell is credited with the artwork used for the film; he created the design for the space ark that was constructed. The final scene in the film, the sunrise landscape on Zyra, was taken from a Bonestell sketch. Because of budget constraints, the director was forced to use this color sketch rather than a finished matte painting.

The additional poor quality still image showing a drowned New York City is often attributed to Bonestell, but it was not actually drawn by him.[6]

UCLA's differential analyzer is shown briefly near the beginning of the film; it verifies the initial hand-made calculations confirming the coming destruction of the Earth. "There is no error".[4]

Producer George Pal considered making a sequel based on the second novel, After Worlds Collide, but the box office failure of his 1955 Conquest of Space made that impossible.[4]

Reception

When Worlds Collide was reviewed by Bosley Crowther of The New York Times, who noted that George Pal had followed up on his other prophetic epic, Destination Moon: "... this time the science soothsayer, whose forecasts have the virtue, at least, of being represented in provocative visual terms, offers rather cold comfort for those scholars who would string along with him. One of the worlds which he arranged to have collide is ours".[7] He reported that "Except for a rustle of applause to salute a perfect pancake landing, the drowsy audience at the Globe, where the film opened yesterday, showed slight interest. It appeared skeptical and even bored. Mr. Pal barely gets us out there, but this time he doesn't bring us back".[7]

Freelance writer Melvin E. Matthews calls the film a "doomsday parable for the nuclear age of the '50s".[8] Emory University physics professor Sidney Perkowitz notes that When Worlds Collide is the first in a long list of films where "science wielded by a heroic scientist confronts a catastrophe". He calls the special effects exceptional.[9]

Librarian and filmographer Charles P. Mitchell was critical of the "... scientific gaffes that dilute the storyline" and a "failure to provide consistent first-class effects". He stated that there were inconsistencies in the script, citing (incorrectly), the disappearance of Dr. Bronson in the second half of the film.[Note 2] He summarizes that "the large number of plot defects are annoying and prevent this admirable effort from achieving top-drawer status".[5]

Awards

When Worlds Collide won the 1951 Academy Award for special effects. It was also nominated for Best Cinematography-Color.[10]

Comic book adaptation

The film was adapted into a comic book by George Evans. [11]

In popular culture

- When Worlds Collide is one of the many classic films referenced in the opening theme ("Science Fiction/Double Feature") of both the stage musical The Rocky Horror Show (1973) and its cinematic counterpart, The Rocky Horror Picture Show (1976).[12]

- In the feature film Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan (1982), two cargo containers can be seen labeled "Bellus" and "Zyra" in the Genesis Cave.[13]

- In the film adaptation of L.A. Confidential (1997), tabloid writer Sid Hudgens arranges for the publicity-loving Jack Vincennes to arrest a young actor on the night of the premiere of When Worlds Collide, resulting in photos of the arrest with the theater marquee in the background, accompanied by the headline "Movie Premiere Pot Bust" (the scene is shown taking place in 1953, long after the actual 1951 premiere of When Worlds Collide).[14]

- When Worlds Collide is the title of a 1975 album (the related single is "Did Worlds Collide?") by Richard Hudson and John Ford, their third release after leaving Strawbs.[15]

- "When Worlds Collide" is the title of a single by the heavy metal band Powerman 5000 from the 1999 album Tonight the Stars Revolt!.[16]

Remake

The 1998 film Deep Impact originated as a joint remake of When Worlds Collide and an adaptation of the 1993 Arthur C. Clarke novel The Hammer of God, and the project was originally acknowledged as such, although the finished film did not acknowledge any of its sources since it was judged as being different enough to not require it.[17]

Paramount Pictures began preproduction on a remake of When Worlds Collide circa 2013. As of August 25, 2015, no release date had been announced.[18]

References

Notes

- ↑ In the novel, the object that destroys the Earth is another planet. The change to a star makes the film's title inaccurate.

- ↑ On the contrary, Dr. Bronson is clearly mentioned in dialog as arriving at Hendron's camp and is later depicted as being killed when a construction crane falls on him during the devastating passage of Zyra.

Citations

- ↑ ""When Worlds Collide"." Turner Classic Movies. Retrieved: July 20, 2013

- ↑ "The Top Box Office Hits of 1951." Variety, January 2, 1952.

- ↑ Wylie, Philip; Balmer, Edwin (1932). When Worlds Collide. New York City: Lippincott. ASIN B001DABHPS.

- 1 2 3 Warren 1982, pp. 151–163.

- 1 2 Mitchell 2001, pp. 252–254.

- ↑ Miller et al. 2001, p. 65.

- 1 2 Crowther, Bosley. "Movie Review: When Worlds Collide (1951); The screen in review;George Pal's new film adventure into outer space, 'When Worlds Collide,' opens at the Globe". The New York Times, February 7, 1952.

- ↑ "1950s Science Fiction Films and 9/11". google.com.

- ↑ Perkowitz 2007, p. 9.

- ↑ Sullivan et al. 2011, p. 21.

- ↑ https://www.lambiek.net/artists/e/evans.htm

- ↑ Miller 2011, p. 127.

- ↑ "Star Trek cast and crew (August 6, 2002)." Star Trek II: The Wrath of Khan, The Directors Edition: Special Features (DVD; Disc 2/2): Paramount Pictures.

- ↑ Veniere, James. "Director of L.A. Confidential hits stride. Boston Herald. September 14, 1997.

- ↑ "Hudson-Ford – Worlds Collide." discogs.com. Retrieved: January 9, 2015.

- ↑ "Tonight the Stars Revolt!" allmusic.com. Retrieved: January 9, 2015.

- ↑ Shapiro, Mark (May 1998). "When Worlds Collide Anew (On Location for Deep Impact...)". Starlog. New York, US: Starlog Group, Inc. Retrieved July 15, 2017.

- ↑ retrieved December 16, 2015

Bibliography

- Hickman, Gail Morgan. The Films of George Pal. South Brunswick, New Jersey: A. S. Barnes and Company, Inc., 1977. ISBN 978-0-49801-960-9.

- Matthews, Melvin E. Hostile Aliens, Hollywood, and Today's News: 1950s Science Fiction Films and 9/11. New York: Algora Publishing, 2007. ISBN 978-0-87586-498-3.

- Miller, Ron, Chesley Bonestell, Frederick C. Durant and Melvin H. Schuetz. The Art of Chesley Bonestell. New York: HarperCollins, 2001. ISBN 978-1-85585-884-8.

- Miller, Scott. Sex, Drugs, Rock & Roll, and Musicals. Lebanon, New Hampshire: University Press of New England, 2011. ISBN 978-1-55553-761-6.

- Mitchell, Charles P. A Guide to Apocalyptic Cinema. Westport, Connecticut: Greenwood Press, 2001. ISBN 978-0-31331-527-5.

- Perkowitz, S. Hollywood Science: Movies, Science, and the End of the World. New York: Columbia University Press, 2007. ISBN 978-0-23114-281-6.

- Reginald, R. and Douglas Menville. Things to Come: An Illustrated History of Science Fiction Film. New York: Times Books, 1977. ISBN 978-0-81290-710-0.

- Sullivan, III, C. W., Tobias Hochscherf, James Leggott, Donald E. Palumbo, et al., eds. British Science Fiction Film and Television: Critical Essays, Critical Explorations in Science Fiction and Fantasy 29. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 2011. ISBN 978-0-78644-621-6.

- Warren, Bill. Keep Watching the Skies, American Science Fiction Movies of the 50s, Vol. I: 1950 - 1957. Jefferson, North Carolina: McFarland & Company, 1982. ISBN 0-89950-032-3.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: When Worlds Collide |