Weser-Rhine Germanic

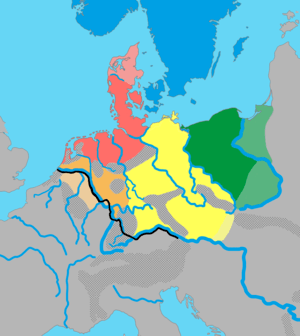

Weser-Rhine Germanic (German Weser-Rhein-Germanisch) is a term introduced by the German linguist Friedrich Maurer for the group of prehistoric West Germanic dialects ancestral to Low Franconian and Rhine Franconian, and ultimately to Dutch and the West Central German dialects.[1] It is a replacement for the older term Istvaeonic, with which it is essentially synonymous. The term Rhine-Weser-Germanic is sometimes preferred.[2]

Nomenclature

The term Istvaeonic is derived from the Istævones (or Istvaeones), a culturo-linguistic grouping of Germanic tribes, mentioned by Tacitus in his Germania.[3] Pliny the Elder further specified its meaning by claiming that the Istævones lived near the Rhine.[4] Based on this, Maurer used it to refer to the dialects spoken by the Franks and Chatti around the northwestern banks of the Rhine, presumed descendants of the earlier Istvaeones.[5] The Weser river is a river in Germany, east from, and parallel to, the Rhine. The terms Rhine-Weser or Weser-Rhine are therefore describing the area between these two rivers as a meaningful cultural-linguistic region during the Roman empire.

Theory

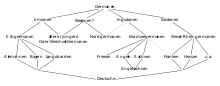

Mauer asserted that the cladistic tree model, ubiquitously used in 19th and early 20th century linguistics, were too inaccurate to describe the relation between the modern Germanic languages, especially those belonging to its Western branch. Rather than depicting Old English, Old Dutch, Old Saxon, Old Frisian and Old High German to have simply 'branched off' of a single common 'Proto-West Germanic', which many previous linguists equated to "Old German / Urdeutsch", he proposed that there was once much more distance between the languages and dialects of the Germanic regions.[6]

Assumed daughter languages

Maurer considered Weser-Rhine Germanic to be the predecessor of Old Frankish. Today, Dutch and related languages such as Afrikaans are generally seen as having descended from Old Frankish. Arguments in favor of viewing Old Dutch as the successor to the Weser-Rhine Germanic dialects include the apparently local origin of Frankish (Old Dutch) in the area previously ascribed to the Istvaeones, and the distinctive phonological, grammatical and idiomatic cluster it forms in contrast to the North-Sea Germanic dialects (Frisian, Anglo-Saxon and Saxon) to its north and the Elbe Germanic dialects (Old High German) to its southeast. Old Dutch and its descendants also include the present-day Meuse-Rhenish/Zuid-Gelders dialects, which are also found in Germany's Lower Rhine region. These dialects form the most isolated and divergent dialectal grouping found within German territory today.[7]

The relationship of the so-called modern Central and Rhine Franconian dialects (including Luxembourgian) with regard to Weser-Rhine Germanic is more difficult to determine. Historically, the speakers of these dialects were seen as the descendants of the Ripuarian Franks, however there is little tangible evidence for this. The last reported position of the Ripuarians (between the Meuse and Moselle river) and the relatively long survival of the Moselle Romance-language in the area they conquered suggest that a large part of the Ripuarii eventually assimilated into the Northern French cultural sphere, as was the case among the Salian Franks who settled below the Somme and Oise. The remainder, most likely situated between modern Luxemburg and Cologne, was subsequently heavily influenced by Germanic tribes speaking Old High German. The influence of these Old High German speakers is not to be underestimated as the general consensus among linguists is that the presence of the High German consonant shift in the Franconian dialects is not the result of internal change, but external influences.[8][9] How this came to be, is a matter of discussion. Proponents of the "repression theory / Zurückdrängungstheorie" argue that the area was originally populated by speakers of High German dialects, which were then subjected to a Frankish (i.e. Weser-Rhine Germanic) superstratum following political submission of the area, corresponding to the 6th century conquests of Clovis.[10] Other linguists argue that Weser-Rhine Germanic forms the substrate in these dialects, which were subsequently influenced by High German.[11]

References

- ↑ Maurer 1942, pp. 123–126, 175–178.

- ↑ Henriksen & van der Auwera 1994, p. 9.

- ↑ Tac. Ger. 2

- ↑ Plin. Nat. 4.28

- ↑ Maurer 1952.

- ↑ Johannes Hoops, Heinrich Beck, Dieter Geuenich, Heiko Steuer: Reallexikon der germanischen Altertumskunde: Band 7; Walter de Gruyter, 1989, ISBN 9783110114454 (pp 113–114).

- ↑ Einführung in die Dialektologie des Deutschen, H. Niebaum. Abb. 25 & Abb 26. (2014)

- ↑ Deutsch: Eine Sprachgeschichte bis 1945, Christopher J. Wells (1991) pp. 461

- ↑ Einführung in die Dialektologie des Deutschen, Hermann Niebaum (2014)

- ↑ Language Change and Language Structure, T. Swan. pp. 281-282 (1994)

- ↑ Deutsch: Eine Sprachgeschichte bis 1945, Christopher J. Wells (1991) pp. 461-2

Bibliography

- Tacitus, Germania (1st Century AD). (in Latin)

- Gregory of Tours (1997) [1916]. Halsall, Paul, ed. History of the Franks: Books I–X (Extended Selections). Medieval Sourcebook. Translated by Ernst Brehaut. Columbia University Press; Fordham University.

- Henriksen, Carol; van der Auwera, Johan (2013) [First published 1994]. "1. The Germanic Languages". In van der Auwera, Johan; König, Ekkehard. The Germanic Languages. London, New York: Routledge. pp. 1–18. ISBN 0-415-05768-X.

- Maurer, Friedrich (1952) [First edition 1942]. Nordgermanen und Alemannen: Studien zur germanische und frühdeutschen Sprachgeschichte, Stammes- und Volkskunde. Bibliotheca Germanic, 3 (3rd, revised, extended ed.). Bern, Munich: Francke.

- James, Edward (1988). The Franks. The Peoples of Europe. Oxford, UK; Cambridge, Massachusetts: Basil Blackwell. ISBN 0-631-17936-4.