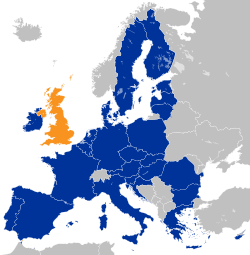

Continuing United Kingdom relationship with the European Union

The United Kingdom's post-Brexit relationship with the remaining European Union members could take several forms. A research paper presented to the UK Parliament in July 2013 proposed a number of alternatives to membership which would continue to allow access to the EU internal market. These include remaining in the European Economic Area (EEA) as a European Free Trade Association (EFTA) member (alongside Iceland, Liechtenstein, and Norway), or seeking to negotiate bilateral terms more akin to the Swiss model with a series of interdependent sectoral agreements.[1] The exit from the EU without EEA membership or a trade agreement is known as the WTO option.

A transitional arrangement may apply between the time the UK leaves the EU and the coming into force of the final relationship. The report from the first phase of Brexit negotiations (June to December 2017) mentioned the possibility of agreeing a transitional arrangement during the second phase.[2]

UK membership of the European Economic Area

The UK could seek to continue to be a member of the European Economic Area as a member of EFTA. In January 2017, Theresa May, the British Prime Minister, announced a 12-point plan of negotiating objectives and said that the UK government would not seek continued membership in the single market.[3] EEA membership would mean being under existing EU internal market legislation that is part of the EEA Agreement. Some EU law originates from various international bodies on which non-EU EEA countries have a seat. EFTA members are free to set their own policies in areas such as agriculture, fisheries, Customs Union, trade, the Common Foreign and Security Policy, direct and indirect taxation and criminal matters.[4] EEA countries are required to contribute to the EU Budget in exchange for access to the internal market.[5][6] The UK would be subject to the EFTA Court rather than the European Court of Justice.[7]

Bilateral deals

Seeking to negotiate bilateral terms more along the Swiss model with a series of interdependent sectoral agreements.[1] Britain has not negotiated a trade agreement since before 1973, and the government is looking to the private sector for assistance.[8]

WTO option

The WTO option would involve the United Kingdom leaving the European Union without any Free Trade Agreement and relying on the trading rules set by the World Trade Organization.[9]

Immigration

The EEA Agreement and the agreement with Switzerland cover free movement of goods, and free movement of people.[10][11] Many supporters of Brexit want to restrict freedom of movement;[12] Liechtenstein has a de facto permanent limit on the free movement of persons, though the EEA Joint Committee said this was because of Liechtenstein's specific geographical situation.[13] Also, an EEA Agreement would include free movement for EU and EEA citizens, although the EEA Agreement allows EEA EFTA states to suspend it temporarily due to serious economic, societal or environmental difficulties.[14] Passport systems allow EEA institutions to access markets in EU Member States, for the most part, without having to establish subsidiaries in each EU Member State and incur the costs of full authorisation in those jurisdiction.[15] Others present ideas of a Swiss solution, that is tailor-made agreements between the UK and the EU, but EU representatives have claimed they would not support such a solution. The Swiss agreements contain free movement for EU citizens.[16] (The Swiss immigration referendum, February 2014 voted narrowly in favour of an end to the 'free movement' agreement, by February 2017. However, the bilateral treaties between Switzerland and the European Union are all co-dependent: if one is terminated then all are terminated. Consequently, should Switzerland choose unilaterally to cancel the 'free movement' agreement then all its agreements with the EU will lapse unless a compromise is found. A compromise was reached in December 2016, effectively canceling quotas on EU citizens but still allowing for favorable treatment of Swiss-based job applicants c).[17]

Several thousand British citizens resident in other EU countries have after the referendum applied for citizenship where they live, since they fear losing the right to work there.[18]

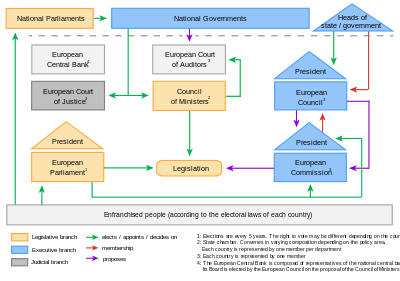

Governance

An EU position paper stated: “The Withdrawal Agreement should establish institutional arrangements to ensure the effective management, implementation and enforcement of the Agreement. It should include appropriate dispute settlement mechanisms regarding the application and interpretation of the Withdrawal Agreement. The Withdrawal Agreement should respect the Union's autonomy. The Withdrawal Agreement should provide that both The Union and the United Kingdom supervise the implementation of the Withdrawal Agreement.”[19]

References

- 1 2 "Leaving the EU – RESEARCH PAPER 13/42" (PDF). House of Commons Library. 1 July 2013. Retrieved 19 May 2015.

- ↑ "Joint report from the negotiators of the European Union and the United Kingdom Government on progress during phase 1 of negotiations under Article 50 TEU on the United Kingdom's orderly withdrawal from the European Union" (PDF). European Commission. 8 December 2017. Retrieved 11 December 2017.

- ↑ Wilkinson, Michael (17 January 2017). "Theresa May confirms Britain will leave Single Market as she sets out 12-point Brexit plan". The Daily Telegraph. Retrieved 18 January 2017.

- ↑ "The Basic Features of the EEA Agreement". European Free Trade Association. Retrieved 8 August 2013.

- ↑ Glencross, Andrew (March 2015). "Why a British referendum on EU membership will not solve the Europe question". International Affairs. 91 (2): 303–17. doi:10.1111/1468-2346.12236.

- ↑ "EEA EFTA Budget". EFTA. Retrieved 14 February 2016.

- ↑ "A&O Legal Opinion on EEA membership"

- ↑ Parker; George (4 July 2016). "Britain turns to private sector for complex Brexit talks". Financial Times. Retrieved 5 July 2016.

- ↑ LeaveHQ. "What's wrong with the WTO Option?". leavehq.com.

- ↑ "Free Movement of Capital", "EFTA". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ "Free Movement of Persons", "EFTA". Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Grose, Thomas. "Anger at Immigration Fuels the UK's Brexit Movement", U.S. News & World Report, Washington, D.C., 16 June 2016. Retrieved 24 June 2016.

- ↑ Pelkmans, Jacques; Bohler (2013). The EEA Review and Liechtenstein's Integration Strategy (PDF). Brussels: Centre for European Policy Studies. p. 34. ISBN 978-94-6138-287-0.

The EEA Council recognises that Liechtenstein has a very small inhabitable area of rural character with an unusually high percentage of non-national residents and employees. Moreover, it acknowledges the vital interest of Liechtenstein to maintain its own national identity.

- ↑ http://www.allenovery.com/Brexit-Law/Documents/Macro/EU/AO_BrexitLaw_-_EEA_Membership_Jul_2016.PDF

- ↑ Brennand, David A.; Jackson, Carolyn H.; Lalone, Nathaniel W.; Robson, Neil; Sugden, Peter (24 June 2016). "Brexit: Implications for the Financial Services Industry". The National Law Review. Katten Muchin Rosenman LLP. Retrieved 28 June 2016.

- ↑ "Agreement with the Swiss Federation: free movement of persons". European Commission. Retrieved 14 July 2016.

- ↑ EU and Switzerland agree on free movement EUobserver, 22 December 2016

- ↑ Sophia Schirmer (19 October 2016). "Huge increase in Britons seeking citizenship in EU states as Brexit looms". The Guardian. Retrieved 24 February 2017.

- ↑ "Position paper transmitted to EU27 on Governance". European Commission - European Commission.