Voltairine de Cleyre

| Voltairine de Cleyre | |

|---|---|

.jpg) Voltairine de Cleyre in Philadelphia, 1901 (age 35) | |

| Born |

November 17, 1866 Leslie, Michigan |

| Died |

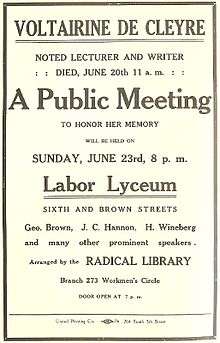

June 20, 1912 (aged 45) St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital in Chicago, Illinois |

| Occupation | writer, lecturer, tutor |

Voltairine de Cleyre (November 17, 1866 – June 20, 1912) was an American anarchist, known for being a prolific writer and speaker, and opposing capitalism, the state, marriage, and the domination of religion over sexuality and women's lives. She is often characterized as a major early feminist because of her views.[1]

Born and raised in small towns in Michigan, and schooled in a Sarnia, Ontario Catholic convent, de Cleyre began her activist career in the freethought movement. She was initially drawn to individualist anarchism but evolved through mutualism to an "anarchism without adjectives," prioritizing a stateless society without the use of force above all else. She was a contemporary of Emma Goldman, with whom she maintained a relationship of respectful disagreement on many issues. Many of her essays were collected in the Selected Works of Voltairine de Cleyre, published posthumously in 1914 by Goldman's magazine, Mother Earth.

Life

Born in the small town of Leslie, Michigan,[2] she moved with her family to St. Johns, Michigan,[3] where she lived with her unhappily married parents in extreme poverty. Her father, Hector Auguste de Cleyre, named her after the famed French Enlightenment author Voltaire.[2]

At age 12, her father placed her in a Catholic convent school in Sarnia, Ontario, [2] because he thought it would give her a better education than the public schools. This experience resulted in her embracing atheism rather than Christianity. Of her time spent there she said, "it had been like the Valley of the Shadow of Death, and there are white scars on my soul, where ignorance and superstition burnt me with their hell fire in those stifling days".[4] She tried to run away by swimming across the St. Clair River to Port Huron, Michigan, and hiking 17 miles (27 km); but she met friends of her family. They contacted her father and sent her back to the convent.[2]

Family ties to the abolitionist movement and the Underground Railroad, the harsh and unrelenting poverty of her childhood, and being named after the philosopher Voltaire - all contributed to the radical rhetoric that she developed shortly after adolescence. After schooling in the convent, de Cleyre moved to Grand Rapids, Michigan. She got involved in the strongly anti-clerical freethought movement by lecturing and contributing articles to freethought periodicals, eventually becoming the editor of a freethought newspaper titled The Progressive Age.[5]

During her time in the freethought movement in the mid and late 1880s, de Cleyre was especially influenced by Thomas Paine, Mary Wollstonecraft and Clarence Darrow. Other influences were Henry David Thoreau, and labor leaders Big Bill Haywood and Eugene Debs. After the 1887 execution of several Haymarket protesters in Chicago, although the police were documented as causing the deaths at the riot, however, she became an anarchist. "Till then I believed in the essential justice of the American law of trial by jury," she wrote in an autobiographical essay, "After that I never could".[4]

She was known as an excellent speaker and writer. Biographer Paul Avrich said that she was "a greater literary talent than any other American anarchist."[6] She was also known as a tireless advocate for the anarchist cause, whose "religious zeal," according to Goldman, "stamped everything she did."[7]

She became pregnant by James B. Elliot, another freethinker, and gave birth to their son, Harry, on June 12, 1890. As de Cleyre and Elliot agreed, Harry lived with Elliot and de Cleyre had no part in his upbringing. She was close to and inspired by Dyer D. Lum ("her teacher, her confidant, her comrade", according to Goldman.[8]) Her relationship with him ended shortly before he committed suicide in 1893.

De Cleyre based her operations from 1889 to 1910 in Philadelphia, where she lived among poor Jewish immigrants, and where sympathy for anarchist beliefs was common. There, she taught English and music, and she learned to speak and write in Yiddish.[9]

Throughout her life de Cleyre was plagued by illness. Goldman said that she had "some disease of the nervous system which she had developed in early childhood,"[2] and she suffered from depression, attempting suicide on at least two occasions.

She survived an assassination attempt on December 19, 1902. Her assailant, Herman Helcher, was a former pupil who had earlier been rendered insane by a fever, and whom she immediately forgave. She wrote, "It would be an outrage against civilization if he were sent to jail for an act which was the product of a diseased brain".[10] The attack left her with chronic ear pain and a throat infection that often adversely affected her ability to speak or concentrate.

During the spring of 1911 she was encouraged by the revolution in Mexico, and especially by the activities of anarchist Ricardo Flores Magón. Her last poem was dedicated to the Mexican activists.

Voltairine de Cleyre died from septic meningitis on June 20, 1912, at St. Mary of Nazareth Hospital in Chicago, Illinois. She is interred near the Haymarket defendants, and other social activists at the Waldheim Cemetery (now Forest Home Cemetery), in Forest Park, a suburb west of Chicago. Emma Goldman was later buried in this area of the cemetery as well.[11]

Political beliefs

De Cleyre changed her political perspective during her life. She eventually became a strong proponent of "anarchism without adjectives," a doctrine, according to historian George Richard Esenwein, "without any qualifying labels such as communist, collectivist, mutualist, or individualist. For others, … [it] was simply understood as an attitude that tolerated the coexistence of different anarchist schools."[12]

For several years de Cleyre associated primarily with American individualist anarchism. Distinguishing herself from Emma Goldman, and expanding on her support for individualist anarchism, de Cleyre wrote,

"Miss Goldman is a communist; I am an individualist. She wishes to destroy the right of property, I wish to assert it. I make my war upon privilege and authority, whereby the right of property, the true right in that which is proper to the individual, is annihilated. She believes that co-operation would entirely supplant competition; I hold that competition in one form or another will always exist, and that it is highly desirable it should."[13]

Despite their early dislike for one another, de Cleyre and Goldman came to respect each other intellectually. In her 1894 essay "In Defense of Emma Goldman and the Right of Expropriation", de Cleyre wrote in support of the right of expropriation:

"I do not think one little bit of sensitive human flesh is worth all the property rights in N. Y. city … I say it is your business to decide whether you will starve and freeze in sight of food and clothing, outside of jail, or commit some overt act against the institution of property and take your place beside Timmermann and Goldmann."[13]

Eventually, however, de Cleyre embraced social anarchism over individualism. In 1908 she argued "that the best thing ordinary workingmen or women could do was to organise their industry to get rid of money altogether" and "produce together, co-operatively rather than as employer and employed."[14] In 1912 she said that the Paris Commune's failure was due to its having "respected [private] property." In her essay, "The Commune Is Risen", she states that "In short, though there were other reasons why the Commune fell, the chief one was that in the hour of necessity, the Communards were not Communists. They attempted to break political chains without breaking economic ones…".[15] She became an advocate of anarchism without adjectives, writing, "I no longer label myself otherwise than as 'Anarchist' simply", in The Making of an Anarchist.[16]

Some observers and scholars dispute whether de Cleyre's rejection of individualism constituted an embrace of pure communism. Rudolf Rocker and Emma Goldman asserted that position, but others, including de Cleyre's biographer Paul Avrich, have not agreed.[17] In response to claims that she had been an anarchist communist, de Cleyre said in 1907 that "I am not now, and have never been at any time, a communist."[18] Anarchist scholar Iain McKay argues that de Cleyre's subsequent 1908 advocacy of a moneyless economy was technically a form of (libertarian) communism, even if she rejected the word "communist" to describe it.[19]

In her 1901 essay titled Anarchism, de Cleyre wrote,

"My ideal would be a condition in which all natural resources would be forever free to all, and the worker individually able to produce for himself sufficient for all his vital needs, if he so chose, so that he needs not govern his working or not working by the times and seasons of his fellows. I think that time may come; but it will only be through the development of the modes of production and the taste of the people. Meanwhile we all cry with one voice for the freedom to try".[20]

"Direct Action", her 1912 essay in defense of direct action, is widely cited today. In this essay, de Cleyre points to examples such as the Boston Tea Party, noting that "direct action has always been used, and has the historical sanction of the very people now reprobating it."[21]

In her 1895 lecture entitled Sex Slavery, de Cleyre condemns ideals of beauty that encourage women to distort their bodies, and child socialization practices that create unnatural gender roles. The title of the essay refers not to traffic in women for purposes of prostitution, although that is also mentioned, but rather to marriage laws that allow men to rape their wives without consequences. Such laws make "every married woman what she is, a bonded slave, who takes her master's name, her master's bread, her master's commands, and serves her master's passions."[22]

De Cleyre adamantly opposed the government maintaining a standing army, arguing that its existence made wars more likely. In her 1909 essay, "Anarchism and American Traditions," she argued that in order to achieve peace, "all peaceful persons should withdraw their support from the army, and require that all who wish to make war do so at their own cost and risk; that neither pay nor pensions are to be provided for those who choose to make man-killing a trade."[23]

Legacy

Voltairine de Cleyre was a prominent American anarchist. One of the few women of stature in the anarchist movement, she was acclaimed by Emma Goldman as "the most gifted and brilliant anarchist woman America ever produced".[17][24] Today she is not widely known, which biographer Sharon Presley attributes to the shortness of her life.[17]

Since the late 20th century, there has been renewed interest in her: An American Anarchist, written by Paul Avrich, was published by the Princeton University Press in 1978. A collection of her speeches, The First Mayday: The Haymarket Speeches, 1895–1910, was published by the Libertarian Book Club in 1980. In 2004, AK Press released The Voltairine de Cleyre Reader.[25] In 2005, two more collections of her speeches and articles were published: Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine De Cleyre – Anarchist, Feminist, Genius, edited by Presley and Crispin Sartwell, and published by SUNY Press,[26] and Gates of Freedom: Voltairine De Cleyre and the Revolution of the Mind, from University of Michigan Press.[27] Her papers are held at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research in New York City.[28] In 2018, the New York Times published a belated obituary for her.[29]

See also

- Eugene Debs

- Emma Goldman

- Haymarket affair

- Bill Haywood

- The writing on the wall – influenced de Cleyre's Written in Red

- Dyer D. Lum

- Henry David Thoreau

References

- ↑ Presley, Sharon (February 18, 2000). "Libertarian Feminist Heritage Series: Voltairine de Cleyre". Anarchy Archives. Retrieved December 17, 2016.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Goldman, Emma. "Voltairine De Cleyre". The Emma Goldman Papers. Retrieved Aug 28, 2013.

- ↑ "Lost Lansing: Leslie's Voltairine de Cleyre shattered the bounds of convention". Lansing Online News. Retrieved Aug 28, 2013.

- 1 2 De Cleyre 2004, p. 106

- ↑ Mob Work: Anarchists in Grand Rapids, Vol. 1 (Grand Rapids, MI: Sprout Distro, 2014), pgs. 26-28

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005, p. 20

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005, p. 331

- ↑ De Cleyre 2004, p. iv

- ↑ "People & Events: Voltairine de Cleyre (1866–1912)". PBS. Retrieved Aug 28, 2013.

- ↑ De Cleyre 2004, p. ix

- ↑ De Cleyre 2004, p. x

- ↑ Esenwein 1989, p. 135

- 1 2 De Cleyre 2005, p. 156

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005, p. 62

- ↑ DeLamotte 2005, p. 206

- ↑ De Cleyre 2004, p. 108

- 1 2 3 Presley 1979

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005, p. 22

- ↑ McKay, Iain (Summer 2006), "Voltairine De Cleyre: Her revolutionary ideas and legacy", Anarcho-Syndicalist Review (44), retrieved 2008-12-14

- ↑ de Cleyre, Voltairine. "Anarchism". Panarchy.org. Free Society. Retrieved 8 June 2016.

- ↑ De Cleyre 2004, p. 50

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005, p. 228

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005, p. 101

- ↑ Falk 2003, p. 195

- ↑ De Cleyre 2004

- ↑ De Cleyre 2005

- ↑ DeLamotte 2005

- ↑ Voltairine de Cleyre and Joseph Jacob Cohen Papers. RG 1485. YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, NY

- ↑ "Overlooked No More: Voltairine de Cleyre, America's 'Greatest Woman Anarchist' - The New York Times". Nytimes.com. Retrieved 2018-10-01.

Bibliography

- Avrich, Paul (1978), An American Anarchist: The Life of Voltairine de Cleyre, Princeton: Princeton University Press, ISBN 0-691-04657-3

- De Cleyre, Voltairine; Alexander Berkman; Hippolyte Havel (1914), Selected Works of Voltairine de Cleyre, New York: Mother Earth Publishing Association, OCLC 170244

- De Cleyre, Voltairine (2004), A. J. Brigati, ed., The Voltairine De Cleyre Reader, Oakland, California: AK Press, ISBN 1-902593-87-1

- De Cleyre, Voltairine (2005), Sharon Presley and Crispin Sartwell, ed., Exquisite Rebel: The Essays of Voltairine De Cleyre – Anarchist, Feminist, Genius, Albany: State University of New York Press, ISBN 0-7914-6094-0

- De Cleyre, Voltairine (2008), Normand Baillargeon and Chantal Santerre, ed., D'espoir et de raison: Écrits d'une insoumise, Montréal: Lux, ISBN 978-2-89596-066-9

- DeLamotte, Eugenia C. (2004), Gates of Freedom: Voltairine de Cleyre and the Revolution of the Mind, Ann Arbor: University of Michigan Press, ISBN 0-472-09867-5

- Esenwein, George (1989), Anarchist Ideology and the Working-Class Movement in Spain, 1868–1898, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-06398-8

- Falk, Candace (2003), A Documentary of the American Years: Made for America 1890–1901 v. 1, Berkeley: University of California Press, ISBN 0-520-08670-8

- Goldman, Emma (1932), Voltairine de Cleyre (PDF), Berkeley Heights, New Jersey: The Oriole Press, OCLC 12414567, retrieved 2016-06-26

- Marsh, Margaret S. (1981), Anarchist Women, 1870–1920, Philadelphia: Temple University Press, ISBN 0-87722-202-9

- McKay, Iain (Summer 2006), "Voltairine De Cleyre: Her revolutionary ideas and legacy", Anarcho-Syndicalist Review (44), retrieved 2008-12-14

- Presley, Sharon (Winter 1979), "Exquisite Rebel: Voltairine de Cleyre", The Storm! (8), retrieved 2008-12-14

- Presley, Sharon (Fall–Winter 2000), "No Authority But Oneself: The Anarchist Feminist Philosophy of Autonomy and Freedom", Social Anarchism (27), retrieved 2008-12-14

- Riggenbach, Jeff (May 14, 2006), "New & Recent Books: The Ecumenical Spirit and the Libertarian Movement", Rational Review, retrieved 2008-12-14

Further reading

- Dougherty, Michael B. (September 27, 2018). "Overlooked No More: Voltairine de Cleyre, America's 'Greatest Woman Anarchist'". The New York Times. ISSN 0362-4331.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Voltairine de Cleyre |

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Voltairine de Cleyre |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Voltairine de Cleyre. |

- Voltairine.org – Web site about Voltairine de Cleyre, including articles and biography

- Works by Voltairine de Cleyre at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Voltairine de Cleyre at Internet Archive

- Works by Voltairine de Cleyre at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Works by Voltairine de Cleyre at Google Books

- Voltairine de Cleyre entry at the Anarchy Archives

- Poems by Voltairine De Cleyre from the Daily Bleed

- In Defense of Emma Goldman and the Right of Expropriation by Voltairine de Cleyre

- At the Molinari Institute – (near the bottom of the page)

- Riggenbach, Jeff (June 17, 2010), "Voltairine de Cleyre: Penitent Priestess of Anarchism", Mises Daily, Ludwig von Mises Institute

- Voltairine de Cleyre at Find a Grave

- Voltairine de Cleyre, Selected Writings

- Voltairine de Cleyre and Joseph Jacob Cohen Papers held at the YIVO Institute for Jewish Research, New York, NY.