Violin Concerto (Brahms)

| Violin Concerto | |

|---|---|

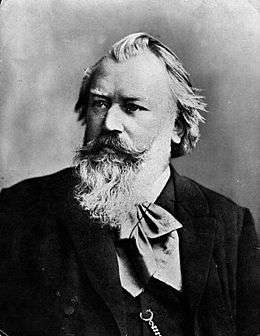

| by Johannes Brahms | |

| |

| Key | D major |

| Catalogue | Op. 77 |

| Period | Romantic |

| Genre | Concerto |

| Composed | 1878 |

| Movements | 3 |

| Scoring | Violin & Orchestra |

| Premiere | |

| Date | 1 January 1879 |

| Location | Leipzig |

The Violin Concerto in D major, Op. 77, was composed by Johannes Brahms in 1878 and dedicated to his friend, the violinist Joseph Joachim. It is Brahms's only violin concerto, and, according to Joachim, one of the four great German violin concerti:[1]

The Germans have four violin concertos. The greatest, most uncompromising is Beethoven's. The one by Brahms vies with it in seriousness. The richest, the most seductive, was written by Max Bruch. But the most inward, the heart's jewel, is Mendelssohn's.

Instrumentation

The Violin Concerto is scored for solo violin and orchestra consisting of 2 flutes, 2 oboes, 2 clarinets in A, 2 bassoons; 2 natural horns crooked in D, and 2 natural horns crooked in E, 2 trumpets in D, timpani, and strings. Despite Brahms' scoring for natural (non-valved) horns in his orchestral works, valved horns have always been used in actual performance, even in Brahms' time.[2]

Structure

The concerto follows the standard concerto form, with three movements in the pattern quick–slow–quick:

Originally, the work was planned in four movements like the second piano concerto. The middle movements, one of which was intended to be a scherzo—a mark that Brahms intended a symphonic concerto rather than a virtuoso showpiece—were discarded and replaced with what Brahms called a "feeble Adagio." Some of the discarded material was reworked for the second piano concerto.

Brahms, who was impatient with the minutiae of slurs marking the bowing, rather than phrasing, as was his usual practice, asked Joachim's advice on the writing of the solo violin part.[3] Joachim, who had first been alerted when Brahms informed him in August that "a few violin passages" would be coming in the mail, was eager that the concerto should be playable and idiomatic, and collaborated willingly, but not all his advice was heeded in the final score.[4] The most familiar cadenza, which appears in the first movement, is by Joachim,[5] though a number of people have provided alternatives, including Leopold Auer, Henri Marteau, Max Reger, Fritz Kreisler, Jascha Heifetz, George Enescu, Nigel Kennedy, Augustin Hadelich, Joshua Bell, and Rachel Barton Pine. A recording of the concerto released by Ruggiero Ricci has been coupled with Ricci's recordings of sixteen different cadenzas.

Structural analysis[6]

First movement

The first movement is in a sonata form. It begins with a first theme material in a lengthy introduction by the orchestra. The theme develops and after a brief transition leads to the second theme material in measure 41. The second theme material dies away and the orchestra suddenly bursts in at measure 78 with the closing section. The solo violin enters at measure 90 with a strong statement in martelé followed by a series of chords that bring on the long arpeggio section. After the long arpeggio section, the solo violin finally reaches the first theme in measure 136. The first theme is worked out with its beautiful melodies until it reaches the strong chords in measure 164. The chords again turn to the arpeggio section. The new second theme of the solo exposition is introduced in measure 206. The solo violin bursts in with the closing theme at measure 246. This leads to an intense section that finishes the exposition. The development section has a soulful melody that soon turns into a dreamy passage. After a sudden forte section, the solo violin enters with angular material. The recapitulation begins at measure 381. The coda begins at measure 527 following the cadenza.

Second movement

The second movement is in three parts. The A section begins with the melody by the solo oboe with orchestral accompaniment. Finally, the solo violin takes over the melody in measure 32. The B section begins at measure 56 with a passionate solo violin melody. After an undulating and fiery section, the solo violin returns to the A section in measure 78 with the melody played by the orchestra.

Third movement

The third movement is in a rondo form. The A section begins with a cheery theme by the solo violin and crisp accompaniment underneath it. After a theme played as a double-stops by the solo violin, the B section begins in measure 35 with light solo violin and accompaniment. This soon turns to a series of scales in legato which brings in another rhythmic melody by the solo violin. The solo violin reiterates the main melody in measure 93 which indicates the return of the A section. After the condensed version of the A section, the C section begins in measure 108 with graceful arpeggios. In measure 143, the solo violin enters with the materials from the B section. Finally, the solo violin brings in the main melody from the A section in measure 187. The A section leads to a new section that starts with solo violin alone in measure 222 where the materials are worked out. This section again finishes with a small cadenza by the solo violin in measure 266. The coda begins at measure 267 with a faster tempo marking. In the coda, the melody from the A section is rhythmically reshaped with a quarter note and a triplet. The coda finishes with subito forte chords.

Premiere

The work was premiered in Leipzig on January 1, 1879, by Joachim, who insisted on opening the concert with the Beethoven Violin Concerto, written in the same key, and closing with the Brahms.[7] Joachim's decision could be understandable, though Brahms complained that "it was a lot of D major—and not much else on the program."[8] Joachim was not presenting two established works, but one established one and a new, difficult one by a composer who had a reputation for being difficult.[9] The two works also share some striking similarities. For instance, Brahms has the violin enter with the timpani after the orchestral introduction: this is a clear homage to Beethoven, whose violin concerto also makes unusual use of the timpani.

Brahms conducted the premiere. Various modifications were made between then and the work's publication by Fritz Simrock later in the year.

Critical reaction to the work was mixed: the canard that the work was not so much for violin as "against the violin" is attributed equally to conductor Hans von Bülow and to Joseph Hellmesberger, to whom Brahms entrusted the Vienna premiere,[10] which was however rapturously received by the public.[11] Henryk Wieniawski called the work "unplayable", and the violin virtuoso Pablo de Sarasate refused to play it because he didn't want to "stand on the rostrum, violin in hand and listen to the oboe playing the only tune in the adagio."[10]

Against these critics, modern listeners often feel that Brahms was not really trying to produce a conventional vehicle for virtuoso display; he had higher musical aims. Similar criticisms have been voiced against the string concerti of other great composers, such as Beethoven's Violin Concerto and Hector Berlioz's Harold in Italy, for making the soloist "almost part of the orchestra."[12]

Technical demands

The technical demands on the soloist are formidable, with generous use of multiple stopping, broken chords, rapid scale passages, and rhythmic variation. The difficulty may to some extent be attributed to the composer's being chiefly a pianist.

Nevertheless, Brahms chose the violin-friendly key of D major for his concerto. Since the violin is tuned G–D–A–E, the open strings, resonating sympathetically, add brilliance to the sound. For the same reason, composers of many eras (e.g. Bach, Mozart, Beethoven, Schumann, Tchaikovsky, Sibelius, Prokofiev, Korngold, Wieniawski, and Khachaturian) wrote violin concertos in either D major or D minor.

In popular culture

The third movement is used twice in Paul Thomas Anderson's 2007 film There Will Be Blood, including the end credits.[13]

In Smilla's Sense of Snow by Peter Høeg, Smilla, the protagonist says "I cry because in the universe there is something as beautiful as Kremer playing Brahms' violin concerto".

The violin entrance in the first movement is sampled extensively in Alicia Keys's 2004 song, Karma.

References

- ↑ Steinberg, Michael. "Bruch: Concerto No. 1 in G Minor for Violin and Orchestra, Opus 26". San Francisco Symphony. Archived from the original on 7 November 2014. Retrieved 6 December 2017.

- ↑ Ericson, John. "Brahms and the Orchestral Horn". Arizona State University. Archived from the original on 24 July 2017. Retrieved 10 February 2018.

- ↑ Gal, Hans (1963). Johannes Brahms. New York: Alfred A. Knopf. p. 217.

- ↑ Jan Swafford, Johannes Brahms: a biography 1997:448ff discusses the writing of the Violin Concerto.

- ↑ J. A. Fuller-Maitland, Joseph Joachim, London and New York, J. Lane, 1905, p. 55

- ↑ "An analysis of the Violin concerto of Johannes Brahms".

- ↑ Steinberg, 121.

- ↑ Quoted in Steinberg, 121.

- ↑ Steinberg, 122.

- 1 2 Swafford 1997:452.

- ↑ Brahms reported it to Julius Stockhausen as "a success as good as I've ever experienced". (quoted Swafford 1997:452.

- ↑ Conrad Wilson: Notes on Brahms: 20 Crucial Works (Edinboro, Saint Andrew Press: 2005) p. 62

- ↑ "There Will Be Blood (2007)" ()

Bibliography

- Steinberg, Michael The Concerto (Oxford and New York: Oxford University Press, 1998). ISBN 0-19-510330-0

External links

- Detailed Listening Guide using the recording by Anne-Sophie Mutter and Herbert von Karajan

- Violin Concerto: Scores at the International Music Score Library Project (IMSLP)

Video examples

- Brahms Violin Concerto played by Ida Haendel: Movement 1, Part I, Movement 1, Part II, Movement 1, Part III, Movement 2, Movement 3.

- Brahms Violin Concerto played by Hilary Hahn with the Frankfurt Radio Symphony Orchestra conducted by Paavo Järvi, March 21, 2014 (YouTube channel of "hr-Sinfonieorchester — Frankfurt Radio Symphony", uploaded May 15, 2014).

- Brahms Violin Concerto played by Oscar Shumsky: Movement 1, Part I, Movement 1, Part II, Movement 1, Part III, Movement 2, Movement 3.

- Brahms Violin Concerto played by Aija Izaks: Aija Izaks - Violin. Concerto by Johannes Brahms, 1st movement, Aija izaks- Violin. Concerto by J. Brahms, 1st mvt- continued, 2nd mvt- complete and Concerto by J.Brahms- 3rd mvt - continued