Vinča

| Vinča Винча | |

|---|---|

| Suburban settlement | |

Aerial view on Vinča and the Danube | |

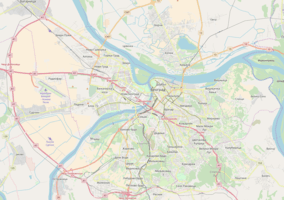

Vinča Location within Belgrade | |

| Coordinates: 44°45′20″N 20°36′47″E / 44.75556°N 20.61306°ECoordinates: 44°45′20″N 20°36′47″E / 44.75556°N 20.61306°E | |

| Country |

|

| Region | Belgrade |

| Municipality | Grocka |

| Area | |

| • Total | 18.95 km2 (7.32 sq mi) |

| Population (2011) | |

| • Total | 6,779 |

| • Density | 360/km2 (930/sq mi) |

| Time zone | UTC+1 (CET) |

| • Summer (DST) | UTC+2 (CEST) |

| Postal code | 11351 |

| Area code | +381(0)11 |

| Car plates | BG |

Vinča (Serbian Cyrillic: Винча, IPA: [ʋîːntʃa]) is a suburban settlement of Belgrade, the capital of Serbia. It is part of the municipality of Grocka. Vinča-Belo Brdo, an important archaeological site that gives its name to the Neolithic Vinča culture, is located in the village.

Location

Vinča is located on the confluence of the Bolečica river into the Danube, on the Danube's right bank, 13 km (8.1 mi) east of Belgrade and 15 km (9.3 mi) west of its own municipal seat of Grocka. It is situated along the stream of Makački potok, which empties into the Bolečica.

Population

| Historical population | ||

|---|---|---|

| Year | Pop. | ±% |

| 1921 | 1,425 | — |

| 1948 | 1,767 | +24.0% |

| 1953 | 2,047 | +15.8% |

| 1961 | 2,247 | +9.8% |

| 1971 | 2,280 | +1.5% |

| 1981 | 3,653 | +60.2% |

| 1991 | 5,067 | +38.7% |

| 2002 | 5,819 | +14.8% |

| 2011 | 6,779 | +16.5% |

| Source: [1] | ||

Vinča is statistically classified as a rural settlement (village). Originally it was situated 3 km from the road of Smederevski put, but as the settlement expanded it now stetches from the Danube to the Smederevski put, making urbanistic connections to the surrounding settlements of Ritopek, Boleč, Leštane and Kaluđerica, though making one continuous built-up area with Belgrade itself. Like the surrounding settlements, Vinča is an immigrant settlement with steady population growth, and the total population number of 6,779 by the 2011 census.

Small bridge across the Bolečica on the Smederevski put marks a place where boundaries of four settlements meet (Vinča, Ritopek, Leštane and Boleč). Together they would make a settlement with the population of 22,345 in 2002 and 26,275 in 2011.

Economy

Vinča's economy is mostly based on agriculture, but it also experiences the most diversity of all the municipal settlements.

The experimental farm of Radmilovac, a section of the Agricultural Faculty of the Belgrade University is located to the east. In 2006 began the reconstruction and expansion of the farm, with new pools and projected covered areas that will turn Radmilovac into and experimental ground for future agricultural production.

The area along the Smederevski put turns into a commercial zone as gas pumps, restaurants, workshops and supermarkets are built. Vinča is on the route of the projected highway in the Bolečica river valley (separating from the Belgrade-Niš highway at Bubanj Potok) and a new bridge over the Danube (Vinča-Omoljica bridge) but a construction date is not yet given.

Tourism is mostly centered on the archeological site of Belo brdo (Serbian for white hill) and the museum of the Vinča culture, with boat trips down the Danube from downtown Belgrade to the small Vinča dock, right below the find, with several fish restaurants on the bank. In order to strengthen the slope below the site, an embankment was built in the early 1980s, which is today a quay along the Danube.[2]

Hotel 'Radmilovac' on the Smederevski put is the major such facility from Belgrade to Smederevo.

Vinča Nuclear Institute

The Vinča Nuclear Institute was officially established on 21 January 1948 by the Serbian top physicist Pavle Savić as the Institute for Physics, though construction of the site began in 1947. On 15 October 1958, the institute was the site of a fatal criticality excursion in its heavy water-moderated research reactor. One researcher was killed and four others injured. The institute operated two research reactors. The larger 6.5 MW reactor achieved criticality in 1959 and was shut down in 1984.[3] Another very low power reactor achieved criticality in 1958 and as of 2002 was operational.[4] The institute was named the Institute for Physical Sciences 'Boris Kidrič' in 1953 and has its present name since 1 January 1992.

In the 1970s a modern urban settlement with small residential buildings was constructed for the employees of the Institute. In 2003, in an effort to secure the radioactive materials from the Institute, the U.S. government aided Serbia in the removal of the material. In 2010, large convoys moved the remaining 2.5 tonnes of nuclear fuel to a reprocessing facility in Mayak in Russia.[5]

Landfill Vinčа

Belgrade's city landfill (deponija) is located in Vinča. Official city landfill from 1960 used to be Ada Huja.[6] When the new General Urban Plan (GUP) was adopted in the early 1970s, the projected location of the new landfill was the marsh around Veliko Selo in the municipality of Palilula. The municipality of Grocka endorsed the GUP, but in 1973 the idea of placing the landfill in Vinča was announced by the city. Grocka rejected the proposal and refused to endorse the new decision but the city administration bypassed the local authorities and the new landfill was opened in Vinča in 1977.[7] As of 2017, the landfill covers an area of 68 ha (170 acres) and receives some 2,700 t (2,700 long tons; 3,000 short tons) of garbage daily, which includes not only the domestic waste but also earth and rubble. Out of 17 city municipalities, 13 use this landfill.[6] The landfill raised many ecological questions for years as only in the 2000s some of the major problems concerning waste managing began to solve. However, despite some recent improvements, the landfill is still far from the European standards of environmental management, like leachate collection and treatment system. It is, as of 2014, not only the Europe's biggest landfill, with between 6,650,000 and 9,500,000 tons of waste deposited in it,[8] but also largest untreated landfill on the continent. Since the city's plan on the waste management for the 2011-202 period, authorities try to make a deal with investors, in the form of the strategic partnership to manage the landfill. As of 2017, they failed.[6] With layers of untreated garbage that reach 70 m (230 ft), the landfill is considered to be the most problematic ecological spot in Europe.[9]

2017 fire

The devastating 2014 Southeast Europe floods triggered a mass wasting in one part of the landfill. As a result of the mass wasting which continued, and of the fact that the waste is not being treated, just piled on the top, a pockets of methane formed deep under the garbage layers. On 18 May 2017 several of these pockets, on different locations and at the depths of 10 to 15 m (33 to 49 ft), bursted into flames. Being covered with dirt and earth, fire above the ground was extinguished quickly, but the smoldering in the deep continued. Wide section of Belgrade was covered in smoke and bad smell, sometimes completely, forcing citizens to use masks. Smoggy neighborhoods included Lešće, Višnjica, Višnjička Banja, Krnjača, Kotež, Borča, Rospi Ćuprija, Karaburma, Slanci and Veliko Selo.[6][10] By 23 May 2017 the smoke reached downtown Belgrade. As the methane fire can't be extinguished with water, it has to be covered with earthy materials which are to isolate methane from oxygen, all trucks bringing earth to the landfill were rerouted to cover the burning section. However as that area is located on the mass wasting ground, it went slow, preventing the quick damping of the fire.[11] As the winds changed, the smoke turned from spreading upstream the Danube to Belgrade, to downstream, in the direction of Smederevo. In order to extinguish the fire completely, for the first time was used a concentrated solution of the brown algae. The preparation acts like the fermentor, organically decomposing the matter, binding methane, ammonia, and oxygen thus preventing the spreading of the fire.[12]

In June smoky haze and bad smell continued to cover parts of Belgrade, especially in the mornings and evenings, and to spread even further, reaching the hilly Dedinje,[13] and more distant Mostar interchange and Vidikovac.[14] City Institute for Public Health continuously issued statements that the levels of the basic pollutants in the air are not above the allowed levels,[6][15] but also admitted that the actions to extinguish the fire are not solving the problem and that "sensitive groups" should "reduce time spent outdoors in the case of smoky haze".[16] Among the substances checked by the Institute are carbon monoxide, nitrogen oxides, sulfur dioxide, ground level ozone, suspended particulate matter below 10 μm (PM 10) and phenols.[17] However, dean of the University of Belgrade's Faculty of Chemistry, Ivan Gržetić, stated that the smoke is not that harmless, since Vinča is not a managed landfill but rather a plain, unregulated dump. He said that the fire probably started years ago at the much deeper level, 20 to 40 m (66 to 131 ft), and that it is highly likely that the fumes contain polychlorinated dibenzofurans and dibenzodioxins, but that Serbia has no special measuring devices to check their levels. He asserted that those compounds are cancerogenic but a good thing is that the smoke is partially dispersed by wind before it reaches the city. He added that Vinča is probably going to burn for years and suggested the piling of the porous pipes which would conduct the methane into the atmosphere.[18] Only then, after almost a month, city administration addressed the issue. Mayor Siniša Mali stated that there is a problem, but not that much of a problem as it is presented, and that "such things happen".[16] In order to prove him that burning garbage is a problem, a group of activists brought two metal barrels under the windows of the City Hall and burned rubbish in them. Commenting on the performance, titled "Greetings from Vinča", Mali said that it is "irresponsible that some five people come to me in front of the City Hall, light fires and scare my people".[19] Acting ombudsman of Serbia, Miloš Janković asked from all involved institutions to make public, not only the results, but also to disclose all information about the way they measure the fumes and a detailed list of all substances covered by those measurements. He was supported by Rodoljub Šabić, state Commissioner for the information of public importance, but the city administration called their initiative "utterly pointless, unjustified and malicious" and that the intended purpose of their action is to "scare the citizens and to raise panic".[20] On 26 June 2017 the city garbage managing company, "Gradska čistoća", announced that after filling of the burning section of the landfill with over 65,000 m3 (2,300,000 cu ft) of earth, the fire was extinguished. Only then, the information that at one point the exploding methane burned on an area of 20 ha (49 acres) (or 30% of the landfill) was disclosed.[21] Still, authorities stated that they can't be sure if the fire was really extinguished in the deep.[22]

Future

On 1 April 2015, city manager Goran Vesić announced that the private strategic partner will be chosen to clean, upgrade, modernize and operate the landfill. He said that by June or July 2015 the invitation for tender will be opened and that the partner will be known by the end of the year. June 2016 was announced as the date when the contract should be signed while January 2020 was set as the date when the new waste-to-energy plant should open. 11 companies applied but in the later phases, that number fell down to 4 or 5, and the city officials (Vesić, mayor Mali, deputy mayor Andreja Mladenović) also couldn't agree on the amount of the investment (ranging from 250 to 400 million) or the duration of the deal (16, 20 or 25 years). In February 2017 Vesić stated that the selection of the bidders is in the finishing phase and that in the first half of 2017 the strategic partner will be selected.[23] On 11 June 2017, during the fire, mayor Mali said that the Vinča problem will be solved on 6 July, when the bids from the "largest world companies" will be opened.[24] The date was moved to 13 July and the deadline for selecting the partner to August.[23] When the bids were opened on 13 July 2017 it turned out there is only one, French-Japanese consortium of Suez-Itochu. If accepted, even in the best case scenario, no work will begin before the second half of 2018. The "Ne davimo Beograd" movement, which opposes the politics of the city administration and continuously organizes the protests and performances, stated that the strategy partnerships for the landfills, in long terms, proves inefficient and unprofitable, citing Barcelona as an example.[25] The city accepted the offer and the contract was signed on 29 September 2017.[26]

Mayor Mali stated that the project as a good investment and that contract is transparent. Political opposition claimed that the contract may be "even more scandalous than the one on Belgrade Waterfront" and openly accused the administration that the entire project is just a scheme to drain money from the city.[27] Partial documentation, though not the full contract, have been handed to the city deputies and was posted online by the Transparency Serbia.[28] The analysis of the City defender's office, needed for the city to adopt the contract, wasn't positive. City defender stated: "Translation of the contract has not be done in accordance with the rules of Serbian language and in case of different interpretations of the Serbian and English versions, precedence has the English version, per Article 71, section 9a of the contract. The English version was not analyzed by the defender's office and the majority of contract is not susceptible to changes. We are also noting that (one) contractual part is also (fiunctioning as) an arbitration and that text of the contract uses legal terms which are not provided by the positive law, therefor we are not in position to confirm, with certainty, whether they are in accordance with the positive law."[29]

Politics

A recent motion, as a result of big economic and demographic discrepancy between the western and eastern parts of the municipality, mentions Vinča of the possible seat of the future municipality formed from the western part of the municipality of Grocka, comprising Kaluđerica, Boleč, Leštane, and Ritopek.

References

- ↑ Comparative overview of the number of population in 1948, 1953, 1961, 1971, 1981, 1991, 2002 and 2011 – Data by settlements, page 29. Statistical Office of the Republic of Serbia, Belgrade. 2014. ISBN 978-86-6161-109-4.

- ↑ Ana Jovanović (2 February 2018). "Automobil uleteo u Dunav, tinejdžer se utopio" [Car fell into the Danube, a teenager got drowned]. Politika (in Serbian). p. 15.

- ↑ "Research Reactor Details - RA". International Atomic Energy Agency. 2002-10-07. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ↑ "Research Reactor Details - RB". International Atomic Energy Agency. 2002-10-04. Retrieved 2007-02-20.

- ↑ "Serbia gets rid of dangerous nuclear material (SETimes.com)". Retrieved 2011-01-02.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Branka Vasiljević (20 May 2017). "Dima još ima, ali vatre nema" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 15.

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (18 July 2017), "Grocka pre 44 godine odbila da se deponija formira u Vinči", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ "The World's 50 Biggest Dumpsites. 2nd Waste Atlas Report". Retrieved 2014-10-17.

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (15 June 2017), "Sanacija – jedino rešenje za deponiju u Vinči", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- ↑ D.K. (19 May 2017). "Dim nad Beogradom: Deponija u Vinči gori već 24 sata, širom grada se oseća smrad. GZZJZ: Nema opasnosti po ljude" (in Serbian). Blic.

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (24 May 2017), "Dim sa deponije štipao za oči i u centur grada", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (27 May 2017), "Irske alge gase požar na deponiji u Vinči", Politika (in Serbian), p. 14

- ↑ Dušan Ivković (7 June 2017), "Beograđani u strahu: Deponija u Vinči gori već 20 dana, pola grada obavijeno dimon i smradom", Blic (in Serbian)

- ↑ "Dim (opet) guši Beograđane: Žalbe stižu iz Vinče, ali i sa Zvezdare, pa čak i Vidikovca", Blic (in Serbian), 10 June 2017

- ↑ "Nisu prekoračene zagađujuće materije u beogradskom vazduhu", Politika (in Serbian), 10 June 2017

- 1 2 "Siniša Mali: Požar na deponiji nije strašan", Istinomer (in Serbian), 12 June 2017

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (13 June 2017). "Glavno žarište na deponiji u Vinči pod kontrolom" (in Serbian). Politika. p. 16.

- ↑ RTS, M.Ro. (9 June 2017), "Opasan dim nad Beogradom: Dekan Hemijskog fakulteta izneo šokantne podatke", Blic (in Serbian)

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (15 June 2017), "Dim iz Vinče „donet" pred Skupštinu grada", Politika (in Serbian), p. 15

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (20 June 2017), "Požar na deponiji u Vinči - Šabić: Objaviti rezultate merenja zagađena vazduha", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Branka Vasiljević (27 June 2017), "U Vinči ni dima ni vatre", Politika (in Serbian), p. 17

- ↑ Dušan Mlađenović (28 June 2017), "Požar na deponiji u Vinči pokazao manjkavosti zakona", N1 (in Serbian)

- 1 2 "Privatni partner za deponiju u Vinči do kraja 2015" (in Serbian). Istinomer. 30 June 2017.

- ↑ Tanjug (11 June 2017). "Mali: Rešenje za Vinču 6. jula" (in Serbian). Radio Television Serbia.

- ↑ Dejan Aleksić (14 July 2017). "Francusko-japanski konzorcijum jedini zainteresovan za deponiju" (in Serbian). Politika.

- ↑ Tanjug (29 September 2017), "Potpisan ugovor za gradnju fabrike za preradu otpada u Vinči", Politika (in Serbian), p. 14

- ↑ BETA (27 September 2017). "Mali: Ugovor za deponiju u Vinči je transparentan, to je dobra investicija" [Contract for the landfill Vinča is transparent, it is a good investment] (in Serbian). Nova Ekonomija.

- ↑ Transparency Serbia - Initiatives and analysis

- ↑ Dobrica Veselinović - Povodom potpisivanja ugovora