Userkaf

| Userkaf | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| Ouserkaf, Woserkaf, Usercherês, Ούσερχέρης | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

_-_046_(cropped).jpg) Head of Userkaf, recovered from his sun temple | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Pharaoh | ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Reign | Seven years in the late 26th to early 25th century BC.[note 1] (5th Dynasty) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Predecessor | Shepseskaf (most likely) or Thamphthis (possibly known as Djedefptah) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Successor | Sahure | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Consort | Neferhetepes (most likely) or Khentkaus I | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Children | Sahure ♂, Khamaat ♀ | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Father | unknown, but belonged to a branch of the Fourth Dynasty royal family in all likelihood | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Mother |

Khentkaus I? Raddjedet (myth) | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

| Monuments |

Pyramid Wab-Isut-Userkaf Pyramid of Neferhetepes Sun temple Nekhenre Temple of Monthu in El-Tod | |||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Userkaf (known in Greek as Usercherês, Ούσερχέρης) was an ancient Egyptian pharaoh, founder of the Fifth Dynasty, reigning for seven to eight in the early 25th century BC. Userkaf belonged in all probability to a branch of the Fourth Dynasty royal family, although his precise parentage remains uncertain and the identity of his queen is equally in doubt. He may have been the son of Khentkaus I marrying Neferhetepes. He had at least one daughter and one son, who would succeed him as pharaoh Sahure.

The reign of Userkaf heralded the ascendency of the cult of Ra, who effectively became Egypt's state-god during the Fifth Dynasty. Userkaf may himself have been a high-priest of Ra prior to acessing to the throne, and in any case, was the first Fifth Dynasty king to build a sun temple, called the Nekhenre, between Abusir and Abu Gurab. In doing so he instituted a tradition that would be followed by his successors over a period of 80 years.

Family

Parents and consort

The identity of Userkaf's parents is not known for certain, but he undoubtedly had family connections with the rulers of the preceding Fourth Dynasty.[25][10][26] The Egyptologist Miroslav Verner proposes that he was a son of Menkaure by one of his secondary queens,[note 2] and even possibly a full brother to his predecessor and last king of the Fourth Dynasty, pharaoh Shepseskaf.[2][27]

Alternatively, the Egyptologist Nicolas Grimal, Peter Clayton and Michael Rice propose that Userkaf may have been the son of a Neferhetepes,[28][29] whom Grimal, Magi and Rice see as a daughter of Djedefre with queen Hetepheres II.[30][31][23] The identity of Neferhetepes' husband in this hypothesis is unknown, with Grimal conjecturing that he may have been the "priest of Ra, lord of Sakhebu", mentioned in Papyrus Westcar.[note 3][33] The Egyptologists Aidan Dodson and Dyan Hilton propose that Neferhetepes was buried in the pyramid next to that of Userkaf,[note 4] which is believed to have belonged to a woman of the same name.[34]

The location of the pyramid attributed to Neferhetepes however strongly suggests that she may instead have been Userkaf's wife and to be identified with the Neferhetepes mother of Userkaf's successor and likely son, Sahure.[35] Indeed, a relief from Sahure's causeway depicts this king and his queen together with the king's mother, identified as a Neferhetepes, which very likely makes her Userkaf's wife.[36] Like Grimal, the Egyptologist Jaromír Malek sees her as a daughter of Djedefre and Hetepheres II.[25] Following this hypothesis, the archaeologist and Egyptologist Mark Lehner also suggests that Userkaf's mother may have been Khentkaus I.[16]

Against such views, Dodson and Hilton note that Neferhetepes is not given the title of king's wife in later documents pertaining to her mortuary cult, although they note that this absence is not necessarily conclusive.[34] They instead propose that Userkaf's queen was Khentkaus I, an hypothesis shared by the Egyptologist Selim Hassan.[34][37] Clayton and Rosalie and Anthony David concur with this hypothesis as well, further positing that Khentkaus I was Menkaure's daughter.[35][38] As a descendant of Djedefre marrying a woman from the main royal branch, the Egyptologist Bernhard Grdseloff argued that Userkaf could have unified rival factions within the royal family thus ending possible dynastic struggles.[13][39]

Alternatively, Userkaf could have been the high priest of Ra prior to ascending the throne with sufficient influence to marry Shepseskaf's widow in the person of Khentkaus I.[note 5][46][47]

Children

Most Egyptologists including Verner, Zemina, David and Baker now believe that Sahure was Userkaf's son rather than his brother as suggested by the Westcar papyrus.[48][49] The main argument in favour of this hypothesis is a relief showing Sahure with his mother Neferhetepes, this being also the name of the queen who owned the pyramid next to that of Userkaf.[36] An additional argument supporting the filiation of Sahure is the location of his pyramid in close proximity to Userkaf's sun temple.[50] No other child of Userkaf has been identified except a daughter named Khamaat, who is mentioned in inscriptions uncovered in the mastaba of Ptahshepses.[51]

Reign

Duration

The exact duration of Userkaf's reign is not known but there is a consensus among Egyptologists that he ruled for seven to eight years based on historical and archeological evidences.[52][53][12][54] First, an analysis of the nearly contemporaneous Old Kingdom royal annals shows that Userkaf's reign was recorded on eight compartements corresponding to at least seven full years but not much more.[note 6][57] The latest legible year recorded on the annals for Userkaf is that of his third cattle count. The cattle count was an important event aimed at evaluating the amount of taxes to be levied on the population. This event is believed to have been biennial during the Old Kingdom period, that is occurring once every two years, meaning that the third cattle count represents his sixth year of year. The same cattle count is also attested by a mason inscription found on a stone of Userkaf's sun temple.[note 7][58] Second, Userkaf is given a reign of seven years on the third column, row 17 of the Turin Royal Canon,[64] a document copied during the reign of Ramses II from earlier sources.[65]

The only historical source favouring a longer reign is the Aegyptiaca, a history of Egypt written in the 3rd century BC during the reign of Ptolemy II (283–246 BC) by Manetho. No copies of the Aegyptiaca have survived to this day and it is now known only through later writings by Sextus Julius Africanus and Eusebius. The Byzantine scholar George Syncellus writes that Africanus relates that the Aegyptiaca mentioned the succession "Usercherês → Sephrês → Nefercherês" at the start of the Fifth Dynasty. Usercherês, Sephrês, and Nefercherês are believed to be the hellenized forms for Userkaf, Sahure and Neferirkare, respectively.[66] In particular, Manetho's reconstruction of the early Fifth Dynasty is in agreement with those given on the Abydos king list and the Saqqara Tablet, two lists of kings writen during the reigns of Seti I and Ramses II, respectively.[67] In constrast with the Turin canon, Africanus' report of the Aegyptiaca credits Userkaf with 28 years of reign,[66] a figure substantially higher than the modern consensus.[52][53][12][54]

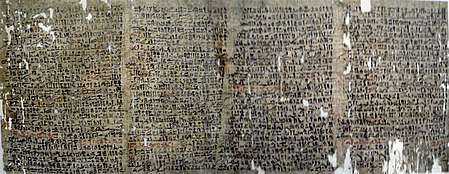

Founder of the Fifth Dynasty

The division of ancient Egyptian kings into dynasties is an invention of Manetho's Aegyptiaca,[16] meant to adhere more closely to the expectations of Manetho's patrons, the Greek rulers of Ptolemaic Egypt. A distinction between the Fourth and Fifth dynasties may nonetheless have been recognised by the Ancient Egyptians, as recorded by a much older tradition[25] manifested in the tale of the papyrus Westcar. In the Westcar story, king Khufu of the Fourth Dynasty is foretold the demise of his line and the rise of a new dynasty through the accession of three brothers, sons of Ra, to the throne of Egypt. The story of the Westcar papyrus dates back to the Seventeenth or possibly the Twelfth Dynasty.[68]

Beyond such historical evidences, the division between the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties seems to reflect actual changes taking place at the time, in particular in the Egyptian religion, as well as changes in the king's role.[69] The primacy of Ra over the rest of Egyptian pantheon in addition to him being the object of much royal devotion effectively made Ra a sort of state-god,[53] a novelty in comparison with the Fourth Dynasty during which the emphasis was rather put on royal burials.[10]

Userkaf's position before ascending to the throne is unknown, Grimal states that he could have been a high-priest of Ra in Heliopolis or Sakhebu, a cult-center of Ra mentioned in the papyrus Westcar. The hypothesis of a relation between the origins of the Fifth Dynasty and Sakhebu was first proposed by the Egyptologist Flinders Petrie, who noted that in Egyptian hieroglyphs the name of Sakhebu resembles that of Elephantine, the city which Manetho's gives as the craddle of the Fifth Dynasty. Positing that the Papyrus Westcar records a tradition which remembered the origins of the Fifth Dynasty, this observation could, according to Petrie, explain Manetho's records especially given that there is otherwise no particular connection between Elephantine and Fifth Dynasty pharaohs.[70]

Activities in Egypt

Beyond the constructions of his mortuary complex and sun temple, little is known of Userkaf's activities during his reign.[4] For Malek his short reign suggests that he was an old man upon becoming pharaoh,[73] while for Verner Userkaf's time on the throne is significant in that it marks the apex of the sun cult,[note 9] the pharaonic title of "Son of Ra" becoming systematic from his reign onwards.[76]

In Upper Egypt, Userkaf might to have commissioned[4] or enlarged[52] the temple of Monthu at Tod, where he is the oldest attested pharaoh.[4] Due the later alterations of the temple in particular during the early Middle Kingdom, New Kingdom and Ptolemaic periods, little of Userkaf's original temple has survived: it seems to have been a small mud-brick chapel including a granite pillar,[77] inscribed with the name of the king.[78]

Further domestic activities may be inferred from the annals of the Old Kingdom, written during Neferirkare's or Nyuserre's reign. The annals record that Userkaf gave endowments for the gods of Heliopolis[note 10] in his second and sixth years[note 11] of reign as well as to the gods of Buto in his sixth year, both of which may have been destined to building projects on Userkaf's behalf.[4] In the same vein, the annals report a donation of land to Horus during Userkaf's sixth year on the throne, this time explicitely mentioning "building [Horus'] temple".[81]

Other gods honoured by Userkaf include Ra and Hathor both of whom received land donations recorded in the annals,[82][79] as well as Nekhbet, Wadjet, the "gods of the divine palace of Upper Egypt" and the "gods of the estate Djebaty" who received bread, beer and land. Finally, a fragmentary piece on text on the annals suggest that Min might also have benefitted from Userkaf's donations.[81] A further evidence for religious activities taking place at the time is given by a royal decree found in the mastaba of the administration official Nykaankh buried at Tihna al-Jabal in Middle Egypt.[22] By this decree, Userkaf donates and reforms several royal domains for the maintenance of the cult of Hathor[83] and installs Nykaankh as priest of this cult.[84]

While Userkaf chose Saqqara to build his pyramid complex, officials at the time continued to build their tombs in the Giza necropolis, including the vizier Seshathotep Heti.[4]

Trade and military activities

Userkaf's reign might have witnessed a recrudescence of trade between Egypt and its Aegean neighbors as shown by a series of reliefs from his mortuary temple representing ships engaged in what may be a naval expedition.[43][85] A further evidence for such contacts is a stone vessel bearing the name of his sun temple that was uncovered on the Greek island of Kythira.[2] This vase is the earliest evidence of commercial contacts between Egypt and the Aegean world,[52] contacts which continued throughout the Fifth Dynasty as attested to by finds dating to the reigns of Menkauhor Kaiu and Djedkare Isesi in Anatolia.[52]

South of Egypt, Userkaf launched a military expedition into Nubia,[2] while the Old Kingdom annals record that he received tribute from a region that is either the Eastern Desert or Canaan in the form of a workforce of one chieftain, 70 foreigners[86] likely women,[87][88][79] as well as 303 "pacified rebels" destined to work on Userkaf's pyramid.[89] These could be prisoners from another military expedition to the East of Egypt[4] or they may represent rebels exiled from Egypt prior to Userkaf's second year on the throne and now willing to reintegrate Egyptian society.[90] According to Hartwig Altenmüller we cannot exclude that these people were punished following Dynastic struggles connected with the end of the Fourth Dynasty.[86]

Statuary

Several fragmentary statues of Userkaf have been uncovered. First is a bust discovered in his sun temple at Abusir, and now on display at the Egyptian Museum. The head of Userkaf is 45 cm (18 in) high and carved from greywacke stone. The sculpture is considered particularly important as it is among the very few sculptures in the round from the Old Kingdom that show the monarch wearing the Deshret of Lower Egypt.[note 12] The head was uncovered in 1957 during the joint excavation expedition of the German and Swiss Institutes of Cairo. Another head which might belong to Userkaf, this time wearing the Hedjet of Upper Egypt and made of painted limestone is known, it is currently on display at the Cleveland Museum of Art.[note 13][17]

The head of a colossal larger-than-life statue of Userkaf, now in the Egyptian Museum, was found in the temple courtyard of his mortuary complex at Saqqarah by Cecil Mallaby Firth in 1928.[92] This colossal head of pink Aswan granite shows the king wearing the nemes headdress with a cobra on his forehead.[35][5] It is the largest surviving head dating to the Old Kingdom period beyond that of the Giza Sphinx[35] and the only colossal royal statue from this time period.[5] Many more fragments of statues of the king made of diorite and granite have been found at the same site.[92]

Sun temple

Significance

Userkaf is the first[2][4] pharaoh to build a dedicated temple to the sun god Ra in the Memphite necropolis north of Abusir, on a promontory on the desert edge[15] just south of the modern locality of Abu Gurab.[94] The only possible predecessor for Userkaf's sun temple was the temple associated with the Great Sphinx of Giza, which may have been dedicated to Ra and may thus have served similar purposes.[95] In any case, Userkaf's successors followed his course of action over a period of 80 years[73] and sun temples were built by all subsequent Fifth Dynasty pharaohs until Menkauhor Kaiu, with the possible[96] exception of Shepseskare whose reign might have been too short to build one.[97] The choice of Abusir on Userkaf's behalf for the construction of his sun temple has not been satisfactorily explained,[98] the site being of no particular significance up to that point.[note 14][93] Yet, Userkaf's choice may[note 15] have influenced subsequent kings of the Fifth Dynasty who made Abusir the royal necropolis until the reign of Menkauhor Kaiu.[101]

For the Egyptologist Hans Goedicke, Userkaf's decision to build a temple for the setting sun separated from his own mortuary complex is the manifestation of and response to social-political tensions, if not turmoil, which happened at the end of the Fourth Dynasty.[69] The construction of the sun temple permitted a distinction between the king's personal afterlife and religious issues pertaining to the setting sun, which had been so closely intertwined in the pyramid complexes of Giza and in the pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty.[102] Thus, Userkaf's pyramid would be isolated in Saqqara, not even surrounded by a wider cemetery for his contemporaries, while the sun temple would serve the social need for a solar cult, which while represented by the king, would not be exclusively embodied by him anymore.[102] Malek similarly sees the construction of sun temples as marking a shift from the royal cult, that was so preponderant during the early Fourth Dynasty, to the cult of the sun god Ra.[53] The king was not revered directly as a god anymore but rather as the son of Ra and this, in turn, changed the royal mortuary cult.

Name

Userkaf's sun temple was called Nekhenre by the Ancient Egyptians, Nḫn Rˁ.w, which has been variously translated as "The fortress of Ra", "The stronghold of Ra", "The residence of Ra",[4] "Ra's storerooms" and "The birthplace of Ra".[103] According to Coppens, Janák, Lehner, Verner, Vymazalová, Wilkinson and Zemina, Nḫn here might actually refer to the town of Nekhen also known as Hierakonpolis rather than just mean "fortress".[15][103][93][95] Hierakonpolis was a stronghold and seat of power for the late predynastic kings who unified Egypt. They propose that Userkaf may have chosen this name to emphasise the victorious and unifying nature of the cult of Ra[93][104] or, at least, to represent some symbolic meaning in relation to kingship.[103] Incidentally, Nekhen was also the name of an institution responsible of providing resources to the living king as well as to his funerary cult after his death.[104] In consequence, the true meaning of Nekhenre might be closer to "Ra's Nekhen" or "The Hierakonpolis of Ra".[103]

Function

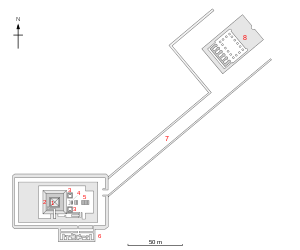

The sun temple of Userkaf first[105] appears in Karl Richard Lepsius' pioneering list of pyramids as pyramid XVII in the mid-19th century.[106] Its true nature was recognised by Ludwig Borchardt in the early 20th century but it was only thoroughly excavated from 1954 until 1957 by a team including Hanns Stock, Werner Kaiser, Peter Kaplony, Wolfgang Helck, and Herbert Ricke.[107][106] According to the royal annals, the construction of the temple started in Userkaf's fifth year on the throne and, on that occasion, he donated 24 royal domains for the maintenance of the temple.[108]

Userkaf's sun temple covered an area of 44 m × 83 m (144 ft × 272 ft)[107] and was oriented to the west. It served primarily as a place of worship for the setting—that is dying—sun and was closely related to the royal mortuary complex with which it shared several architectural elements. These include a valley temple close to the Nile and a causeway leading up to the high temple on the desert plateau. Architectural differences did exist however, for example the valley temple of the sun temple complex is not oriented to any cardinal point, rather pointing vaguely[109] to Heliopolis, and the causeway is not aligned with the axis of the high temple. The Abusir Papyri indicate that the cultic activities taking place in the sun and mortuary temples were related, for example offerings for both cults were dispatched from the sun temple.[104] In fact, sun temples built during this period were meant to play for Ra the same role that the pyramid played for the king: they were funerary temples for the sun god, where his renewal and rejuvenation necessary to maintain the order of the world could take place. Cults performed in the temple were thus primarily concerned with Ra's creator function as well as his role as father of the king. During his lifetime, the king would appoint his closest officials to the running of the temple, allowing them to benefit from the temple's income and thus ensuring their loyalty. After the pharaoh's death, the sun temple's income would be associated with the pyramid complex, supporting the royal funerary cult.[110]

Construction works on the Nekhenre did not stop with Userkaf's death but rather continued in at least four building phases under pharaohs Sahure, Neferirkare Kakai and Nyuserre Ini. By the end of Userkaf's rule, the sun temple did not yet house the large granite obelisk on pedestal that it would subsquently acquire, but rather its main temple seem to have comprised a rectangular enclosure wall with a high mast set on a mound in its center, possibly as a perch for the sun god's falcon.[95] To the east of this mound was a mudbrick altar with statue shrines on both sides of it.[111] According to the royal annals, from his sixth year on the throne onwards, Userkaf commanded that two oxen and two geese were to be sacrified daily in the Nekhenre.[81][95] These animals seem to have been butchered in or around the high temple, the causeway being wide enough to lead live oxen up it.[109]

Pyramid complex

Pyramid of Userkaf

Location

Contrary to his probable immediate predecessor, Shepseskaf, as well as the other pharaohs of the Fourth Dynasty, Userkaf built a modest[22] pyramid for himself at Saqqarah-North, at the north-eastern edge of the wall surrouding Djoser's pyramid complex.[102][112] This decision, probably political,[3] may be connected to the return to city of Memphis as center of government,[102] of which Saqqara to the west is the necropolis, as well as desire to rule according to principles and methods closer to Djoser's.[102] In particular, like Djoser's and contrary to the pyramid complexes of Giza, Userkaf's mortuary complex is not surrounded by a necropolis for his followers.[102] For Goedicke, the wider religious role played by Fourth Dynasty pyramids was now to be played by the sun temple, while the king's mortuary complex was to serve only the king's personal funerary needs.[102] Hence, Userkaf's choice of Saqqara is a manifestation of a return to a "harmonious and altruistic"[102] notion of kingship which Djoser seemed to have symbolized, against that of a Khufu who had almost personally embodied the sun-god.[note 16][99]

Pyramid architecture

Userkaf's pyramid complex was called Wab-Isut Userkaf, meaning "Pure are the places of Userkaf".[113] The pyramid originally reached an height of 49 m (161 ft) for a base-side of 73.3 m (240 ft),[114] making it the second smallest built during the Fifth Dynasty after that of the final king Unas.[115] The pyramid was built following techniques established during the Fourth Dynasty, with a core made of stones rather than employing rubble as in subsequent pyramids of the Fifth and Sixth Dynasties.[116] The core was so poorly laid out however, that once the pyramid's outer casing of fine limestone had been robbed, it crumbled into heap of rubble.[16] The burial chamber was lined with large limestone blocks, its roof made of pented limestone beams.[117]

Mortuary temple

The funerary complex accompanying the pyramid is peculiar in that Userkaf's mortuary temple is located on the pyramid southern side rather than the eastern one as is usually the case, a fact which might be due to the presence of a large moat surrouding Djoser's pyramid and running to the east of the pyramid.[118] This means that Userkaf chose to be buried in close proximity to Djoser even though this implied that he could not use the normal layout for his temple.[118] Alternatively, Userkaf's choice for the temple location on the pyramid southern side may be motivated by religious reasons, with the archeologist Richard H. Wilkinson proposing that it could have ensured its year-round exposition to the sun.[119]

The walls of Userkaf's mortuary temple were extensively adorned in numerous raised-reliefs of exceptional quality.[119][120] Scant remains of pigments on some reliefs show that these were originally painted. Userkaf's pyramid temple represents an important innovation in this respect, he was notably the first pharaoh to introduce nature scenes in his funerary temple including scenes of hunting in the marshes that would become common in subsequent times.[120] The artistic work is highly detailed, with a single relief showing no less than seven different species of birds and a butterfly. Hunting scenes symbolised the victory of king over the forces of chaos and might thus have illustrated Userkaf role as the Iry-Maat that is "the one who establishes the Maat", actually one of Userkaf's names.[120]

Legacy

Funerary cult

Like other pharaohs of the Fourth and Fifth Dynasties, Userkaf benefitted from a funerary cult following his death. This state-sponsored cult relied on goods for the offerings that were produced in dedicated agricultural estates established during the king's lifetime as well as resources such as fabric coming from the "house of silver", that is the treasury.[122] The cult flourished in the early to mid-Fifth Dynasty, as shown by the tombs and seals of priests and officials who participated in it. These include Tepemankh[123] and Senuankh,[124] who served in the cults of both Userkaf and Sahure; Pehenukai a vizier under Sahure and Neferirkare Kakai[125] and Nykuhor, a judge, inspector of scribes, privy councillor, and priest of funerary cults of Userkaf and Neferefre.[126][127]

On a longer term, the relative importance of Userkaf's official cult may be judged by the fact that it was abandonned at the end of the Fifth Dynasty.[52] In comparison, the official funerary cult of some of Userkaf's successors such as Nyuserre Ini lasted until the Middle Kingdom period.[128] The mortuary temple of Userkaf must have been in ruins or dismantled by the time of the Twelfth Dynasty, as some of its decorated blocks depicting the king undertaking a ritual were re-used as building material in the pyramid of Amenemhat I.[129] Userkaf was not the only king whose mortuary temple met this fate, Nyuserre's own temple was targeted even though its last priests were serving in it around this time. These facts hint at a lapse of royal interest in the state-sponsored funerary cults of Old Kingdom rulers.[130]

Examples of personal devotions on behalf of pious individuals perdured much longer, for example Userkaf is depicted on a relief from the Saqqara tomb of the priest Mehu, who lived during the much later Ramesside period.[131][132] Early in this period, during the reign of Ramses II, the pyramid of Userkaf was the object of restoration works undertaken under the impulse of Ramses' fourth son, the prince Khaemwaset (fl. c. 1280–1225 BCE). This is attested by inscriptions on stone cladding from the pyramid field showing Khaemweset with offering bearers.[133]

In contemporary literature

Egyptian Nobel Prize for Literature-winner Najīb Maḥfūẓ published a short story in 1945 about Userkaf entitled Afw al-malik Usirkaf: uqsusa misriya. This short story was translated by Raymond Stock as King Userkaf's Forgiveness in the collection of short stories Sawt min al-ʻalam al-akhar that is Voices from the other world : Ancient Egyptian tales.[134]

Notes, references and sources

Notes

- ↑ Proposed dates for Userkaf's reign: 2560—2553 BC,[1] 2513—2506 BC,[2][3][4][5] 2504—2496 BC,[6] 2498—2491 BC,[7] 2494—2487 BC[8][9][10] 2479—2471 BC,[11] 2466—2458 BC[12] 2465—2458 BC,[13][14][15][16] 2454—2447 BC,[17] 2454—2446 BC,[6] 2435—2429 BC,[18][19] 2392—2385 BC[20]

- ↑ The historians Rosalie and Anthony David concur with such an hypothesis, stating that Userkaf belonged to a side branch of Khafra's family.[10]

- ↑ This papyrus, now recognised as non-historical, records a story according to which Userkaf is a son of the god Ra with a woman named Raddjedet. In the story, two of Userkaf's brothers are said to rise to the throne after him, displacing Khufu's family from the throne.[32]

- ↑ This queen is referred to as Neferhetepes Q in modern Egyptology to distinguish here from preceding women of the same name.[34]

- ↑ Ludwig Borchardt expanded on the theory according to which Khentkaus I was Userkaf's spouse by positing that Userkaf managed to take the throne at the unexpected death of Shepseskaf and before the legitimate heirs Sahure and Neferirkare were old enough to rule.[39] This hypothesis has been conclusively invalidated by recent research which shows that there were two queens Khentkaus, the second one being the mother of Nyuserre Ini,[40][41][42] and that Sahure is Userkaf's son,[43][44] while Neferirkare is Sahure's.[45]

- ↑ Older analyses of the document by Breasted and Daressy had already established that Userkaf reigned 12 to 14 years[55] or 12 to 13 years[56] respectively.

- ↑ Four mentions of the "year of the fifth cattle count" were also discovered on stone tablets from Userkaf's sun temple,[58] which could possibly indicate that Userkaf reigned for 10 years. However, these inscriptions are incomplete, in particular the name of the king's to whose reign they belong is lost, and they might thus instead refer to Sahure's rule[59] or to Neferirkare's[60] rather than that of Userkaf.[61][62] The attribution of these inscriptions to either Sahure or Neferirkare is paramount in determining who completed Userkaf's sun temple, which was unfinished at his death.[58] The tablets detail the division of labour during works on the Nekhenre.[63]

- ↑ The seal is now in the British Museum.[71]

- ↑ Egyptologists including Jürgen von Beckerath rather see Nyuserre's reign as the peak of the solar cult,[74] but for Grimal this is exaggerated.[75]

- ↑ More precisely to the "Bas of Heliopolis".[79]

- ↑ That is, if cattle counts where indeed biennial. The annals only state that the donations happened in the years of the first and third cattle counts.[80]

- ↑ With catalog number JE 90220.[91]

- ↑ The head measures 17.2 cm (6.8 in) in height with a width of 6.5 cm (2.6 in) and a depth of 7.2 cm (2.8 in). Its catalog number is 1979.2.[17]

- ↑ Verner and Zemina report that some Egyptologists, whom they do not name, have proposed that Abusir was chosen as the southernmost point from which one may have been able to glimpse the sun above the obelisk of the religious center of Ra in Heliopolis.[93] This observation is contested by Goedicke[99] and Voß for whom "the supposed proximity to Heliopolis for the choice of the site hardly played a role".[100] Grimal instead conjectures that Abusir was chosen for its proximity to Sakhebu, a locality some 10 km (6.2 mi) north of Abu Rawash, which is mentioned in various sources such as the Westcar Papyrus as a cult center of Ra and which may have been the home town of Userkaf's father, in the hypothesis that he was a grandson of Djedefre.[22]

- ↑ Verner and Zemina are convinced that the presence of Userkaf's sun temple in Abusir explains the subsequent development of the necropolis,[50] but Goedicke sees this only as a "vague association" leaving the choice of Abusir as royal necropolis "inexplicable".[98]

- ↑ Goedicke notes furthermore that the line passing through Userkaf's pyramid and sun temple also passes through the apex of Khufu's pyramid in Giza, an alignment which he believes must be intentional, yet cannot explain.[102]

References

- ↑ Hayes 1978, p. 58.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Verner 2001b, p. 588.

- 1 2 Verner 2001c, p. 91.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Altenmüller 2001, p. 598.

- 1 2 3 El-Shahawy & Atiya 2005, p. 61.

- 1 2 von Beckerath 1997, p. 188.

- ↑ Clayton 1994, p. 60.

- ↑ Malek 2000a, p. 98 & 482.

- ↑ Rice 1999, p. 215.

- 1 2 3 4 David & David 2001, p. 164.

- ↑ von Beckerath 1999, p. 285.

- 1 2 3 Helck 1981, p. 63.

- 1 2 Encyclopædia Britannica 2018.

- ↑ Arnold 1999.

- 1 2 3 Wilkinson 2000, p. 121.

- 1 2 3 4 Lehner 2008, p. 140.

- 1 2 3 CMA 2018.

- ↑ Strudwick 1985, p. 3.

- ↑ Hornung 2012, p. 491.

- ↑ Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 288.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Leprohon 2013, p. 38.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 Grimal 1992, p. 75.

- 1 2 3 Magi 2008, p. 12.

- ↑ Digital Egypt 2018.

- 1 2 3 Malek 2000a, p. 98.

- ↑ Guerrier 2006, p. 414.

- ↑ El-Shahawy & Atiya 2005, p. 33.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 68, Table 2.

- ↑ Rice 1999, p. 131.

- ↑ Rice 1999, pp. 67—68.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 72 & 75.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 70 & 72.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 72—75.

- 1 2 3 4 Dodson & Hilton 2004, p. 65.

- 1 2 3 4 Clayton 1994, p. 61.

- 1 2 Archaeogate Egittologia 2018.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 118.

- ↑ David & David 2001, p. 68.

- 1 2 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 119.

- ↑ Verner 1980a, p. 161, fig. 5.

- ↑ Baud 1999a, p. 234.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 126.

- 1 2 Labrousse & Lauer 2000.

- ↑ Baud 1999b, p. 494.

- ↑ El-Awady 2006, pp. 208–213.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 102 & 118.

- ↑ Verner 2002, p. 263.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 68 & 85.

- ↑ David & David 2001, p. 127.

- 1 2 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 68.

- ↑ Dorman 2002, p. 101 & 107.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 Grimal 1992, p. 76.

- 1 2 3 4 Malek 2000a, pp. 98—99.

- 1 2 von Beckerath 1997, p. 155.

- ↑ Breasted 1906, pp. 68–69, § 153–160.

- ↑ Daressy 1912, p. 206.

- ↑ Hornung 2012, p. 484.

- 1 2 3 Verner 2001a, p. 386.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, p. 388—390.

- ↑ Kaiser 1956, p. 108.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, p. 386—387.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 158.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 158, see also footnote 2.

- ↑ Verner 2001a, p. 385.

- ↑ Hornung 2012, p. 136.

- 1 2 Waddell 1971, p. 51.

- ↑ Daressy 1912, p. 205.

- 1 2 Burkard, Thissen & Quack 2003, p. 178.

- 1 2 Goedicke 2000, pp. 405—406.

- 1 2 Petrie 1897, p. 70.

- ↑ Petrie 1897, p. 71.

- ↑ Petrie 1917, pl. IX.

- 1 2 Malek 2000a, p. 99.

- ↑ von Beckerath 1982, pp. 517–518.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 78.

- ↑ Verner 2002, p. 265.

- ↑ Wilkinson 2000, p. 200.

- ↑ Arnold 1996, p. 107.

- 1 2 3 Strudwick 2005, p. 69.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 69–70.

- 1 2 3 Strudwick 2005, p. 70.

- ↑ Daressy 1912, p. 172.

- ↑ Breasted 1906, pp. 100–106, § 216–230.

- ↑ Breasted 1906, § 219.

- ↑ Allen et al. 1999, p. 324.

- 1 2 Altenmüller 1995, p. 48.

- ↑ Daressy 1912, p. 171.

- ↑ Goedicke 1967, p. 63, n. 34.

- ↑ Baud & Dobrev 1995, p. 33, footnote f.

- ↑ Altenmüller 1995, pp. 47—48.

- ↑ Stadelmann 2007.

- 1 2 Allen et al. 1999, p. 315.

- 1 2 3 4 5 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 102.

- ↑ Quirke 2001, p. 127.

- 1 2 3 4 Lehner 2008, p. 150.

- ↑ Kaplony 1981, A. Text p. 242 and B. pls. 72,8.

- ↑ Verner 2000, pp. 588–589, footnote 30.

- 1 2 Goedicke 2000, p. 408.

- 1 2 Goedicke 2000, p. 407.

- ↑ Voß 2004, p. 8.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 53, 102 & 111.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 Goedicke 2000, p. 406.

- 1 2 3 4 Janák, Vymazalová & Coppens 2011, p. 432.

- 1 2 3 Verner 2002, p. 266.

- ↑ Voß 2004, p. 7.

- 1 2 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 217.

- 1 2 Edel, Ricke & 1965—1969.

- ↑ Breasted 1906, p. 68, § 156.

- 1 2 Lehner 2008, p. 151.

- ↑ Janák, Vymazalová & Coppens 2011, pp. 441–442.

- ↑ Nuzzolo 2007, p. 1402–1403.

- ↑ Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 50.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, p. 116.

- ↑ Arnold 2001, p. 427.

- ↑ Grimal 1992, pp. 76—78.

- ↑ El-Khouly 1978, p. 35.

- ↑ Lehner 2008, p. 141.

- 1 2 Verner & Zemina 1994, p. 53.

- 1 2 Wilkinson 2000, p. 126.

- 1 2 3 El-Shahawy & Atiya 2005, p. 75.

- ↑ Gauthier 1906, p. 42.

- ↑ Desplancques 2006, p. 212.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, Ch.1 § 19.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, Ch.1 § 24.

- ↑ Sethe 1903, Ch.1 § 30.

- ↑ Rice 1999, p. 141.

- ↑ Mariette 1889, p. 313.

- ↑ Morales 2006, p. 336.

- ↑ Strudwick 2005, p. 83.

- ↑ Malek 2000b, p. 257.

- ↑ Gauthier 1906, pp. 41—42.

- ↑ Wildung 1969, pp. 74–76.

- ↑ Verner 1998, p. 308.

- ↑ Mahfouz 2006.

Sources

- Allen, James; Allen, Susan; Anderson, Julie; Arnold, Arnold; Arnold, Dorothea; Cherpion, Nadine; David, Élisabeth; Grimal, Nicolas; Grzymski, Krzysztof; Hawass, Zahi; Hill, Marsha; Jánosi, Peter; Labée-Toutée, Sophie; Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Phillippe; Leclant, Jean; Der Manuelian, Peter; Millet, N. B.; Oppenheim, Adela; Craig Patch, Diana; Pischikova, Elena; Rigault, Patricia; Roehrig, Catharine H.; Wildung, Dietrich; Ziegler, Christiane (1999). Egyptian Art in the Age of the Pyramids. New York: The Metropolitan Museum of Art. ISBN 978-0-8109-6543-0. OCLC 41431623.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (1995). Kessler, Dieter; Schulz, Regine, eds. "Die "Abgaben" aus dem 2. Jahr des Userkaf". Münchner Ägyptologische Untersuchungen, Gedenkschrift für Winfried Barta (in German). 4: 37–48.

- Altenmüller, Hartwig (2001). "Old Kingdom: Fifth Dynasty". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 597–601. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Arnold, Dieter (1996). Die Tempel Ägyptens: Götterwohnungen, Baudenkmäler, Kultstätten (in German). Augsburg: Bechtermünz. ISBN 978-3-86-047215-6.

- Arnold, Dorothea (July 19, 1999). "Old Kingdom Chronology and List of Kings". Metropolitan Museum of Art. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Arnold, Dieter (2001). "Tombs: Royal tombs". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 425–433. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Baud, Michel; Dobrev, Vassil (1995). "De nouvelles annales de l'Ancien Empire Egyptien. Une "Pierre de Palerme" pour la VIe dynastie" (PDF). Bulletin de l'Institut Francais d'Archeologie Orientale (BIFAO) (in French). 95: 23–92. Archived from the original on 2015-04-02.

- Baud, Michel (1999a). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 1 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/1 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7.

- Baud, Michel (1999b). Famille Royale et pouvoir sous l'Ancien Empire égyptien. Tome 2 (PDF). Bibliothèque d'étude 126/2 (in French). Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-7247-0250-7. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2015-04-02.

- Breasted, James Henry (1906). Ancient records of Egypt historical documents from earliest times to the persian conquest, collected edited and translated with commentary. The University of Chicago press. OCLC 778206509. Retrieved August 9, 2018.

- Burkard, Günter; Thissen, Heinz Josef; Quack, Joachim Friedrich (2003). Einführung in die altägyptische Literaturgeschichte. Band 1: Altes und Mittleres Reich. Einführungen und Quellentexte zur Ägyptologie. 1,3,6. Münster: LIT. ISBN 978-3-82-580987-4.

- Clayton, Peter (1994). Chronicle of the Pharaohs. Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-500-05074-3.

- Daressy, Georges (1912). La Pierre de Palerme et la chronologie de l'Ancien Empire (in French). 12. Cairo: Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale. pp. 161–214. Retrieved Aug 11, 2018.

- David, Ann Rosalie; David, Antony E (2001). A biographical dictionary of ancient Egypt. London: Seaby. ISBN 978-1-85-264032-3.

- Desplancques, Sophie (2006). L'institution du Trésor en Egypte: Des origines à la fin du Moyen Empire. Passé Présent (in French). Paris: Presses de l'Université Paris-Sorbonne. ISBN 978-2-84-050451-1.

- Dodson, Aidan; Hilton, Dyan (2004). The Complete Royal Families of Ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05128-3.

- Dorman, Peter (2002). "The biographical inscription of Ptahshepses from Saqqara: A newly identified fragment". Journal of Egyptian Archaeology A. 88: 95–110. JSTOR 3822338.

- Edel, Elmar; Ricke, Herbert (1965). Das Sonnenheiligtum des Königs Userkaf. Beiträge zur ägyptischen Bauforschung und Altertumskunde (in German). 7, 8. Kairo: Schweizerisches Institut für ägyptische Bauforschung und Altertumskunde. OCLC 77668521.

- El-Awady, Tarek (2006). "The royal family of Sahure. New evidence.". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005 (PDF). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.

- El-Khouly, Aly (1978). "Excavations at the Pyramid of Userkaf, 1976: Preliminary Report". The Journal of Egyptian Archaeology. 64 (1): 35–43. doi:10.1177/030751337806400105.

- El-Shahawy, Abeer; Atiya, Farid S. (2005). The Egyptian Museum in Cairo. A walk through the alleys of ancient Egypt. Cairo: Farid Atiya Press. ISBN 978-9-77-171983-0.

- Gauthier, Henri (1906). "Note et remarques historiques III: Un nouveau nom royal". Bulletin de l'Institut Français d'Archéologie Orientale (in French). 5: 41–57.

- Goedicke, Hans (1967). Königliche Dokumente aus den Alten Reich. Ägyptologische Abhandlungen. 14. Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. OCLC 4877029.

- Goedicke, Hans (2000). "Abusir–Saqqara–Giza". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the year 2000. Archív orientální, Supplementa. 9. Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 397–412. ISBN 978-8-08-542539-0.

- Grimal, Nicolas (1992). A History of Ancient Egypt. Translated by Ian Shaw. Hoboken, New Jersey: Wiley-Blackwell publishing. ISBN 978-0-631-19396-8.

- Guerrier, Éric (2006). Les pyramides: l'enquête (in French). Coudray-Macouard: Cheminements, DL. ISBN 978-2-84-478446-9.

- "Head of King Userkaf, c. 2454-2447 BC". The Cleveland Museum of Art. Retrieved Aug 11, 2018.

- Hayes, William (1978). The Scepter of Egypt: A Background for the Study of the Egyptian Antiquities in The Metropolitan Museum of Art. Vol. 1, From the Earliest Times to the End of the Middle Kingdom. New York: Metropolitan Museum of Art. OCLC 7427345.

- Helck, Wolfgang (1981). Geschichte des alten Ägypten. Handbuch der Orientalistik. Abt. 1: Der Nahe und Mittlere Osten. 1. Leiden, Köln: Brill. ISBN 978-9-00-406497-3.

- Hellouin de Cenival, Jean-Louis; Posener-Krieger, Paule (1968). The Abusir Papyri, Series of Hieratic Texts. London: British Museum.

- Hornung, Erik; Krauss, Rolf; Warburton, David, eds. (2012). Ancient Egyptian Chronology. Handbook of Oriental Studies. Leiden, Boston: Brill. ISBN 978-90-04-11385-5. ISSN 0169-9423.

- Janák, Jiří; Vymazalová, Hana; Coppens, Filip (2011). "The Fifth Dynasty 'sun temples' in a broader context". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2010. Prague: Charles University in Prague, Faculty of Arts. pp. 430–442. ISBN 978-8-07-308385-4.

- Kaiser, Werner (1956). "Zu den Sonnenheiligtümern der 5. Dynastie". Mitteilungen des Deutschen Archäologischen Instituts, Abteilung Kairo. 14: 104–116.

- Kaplony, Peter (1981). Die Rollsiegel des Alten Reiches. Katalog der Rollsiegel II. Allgemeiner Teil mit Studien zum Köningtum des Alten Reichs II. Katalog der Rollsiegel A. Text B. Tafeln (in German). Bruxelles: Fondation Egyptologique Reine Élisabeth. ISBN 978-0-583-00301-8.

- Labrousse, Audran; Lauer, Jean-Philippe (2000). Les complexes funéraires d'Ouserkaf et de Néferhétepès. Bibliothèque d'étude, Institut d'archéologie orientale, Le Caire (in French). 130. Cairo: Institut français d'archéologie orientale. ISBN 978-2-72-470263-7.

- Lehner, Mark (2008). The Complete Pyramids. London: Thames & Hudson Ltd. ISBN 978-0-500-05084-2.

- Leprohon, Ronald J. (2013). The great name: ancient Egyptian royal titulary. Writings from the ancient world. 33. Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-736-2.

- Magi, Giovanna (2008). Saqqara: the pyramid, the mastabas and the archaeological site. Firenze: Bonechi. ISBN 978-8-84-761500-7.

- Mahfouz, Naguib (2006). Voices from the other world : Ancient Egyptian tales. Cairo, New York: American University in Cairo Press. ISBN 978-9-77-416029-5.

- Malek, Jaromír (2000a). "The Old Kingdom (c.2160-2055 BC)". In Shaw, Ian. The Oxford History of Ancient Egypt. Oxford University Press. ISBN 978-0-19-815034-3.

- Malek, Jaromir (2000b). "Old Kingdom rulers as "local saints" in the Memphite area during the Old Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000. Prag: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic – Oriental Institute. pp. 241–258. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0.

- Mariette, Auguste (1889). Maspero, Gaston, ed. Les Mastabas de l'Ancien Empire, Fragments du Dernier Ouvrage d'Auguste Édouard Mariette (in French). Paris. OCLC 2654989.

- Morales, Antonio J. (2006). "Traces of official and popular veneration to Nyuserra Iny at Abusir. Late Fifth Dynasty to the Middle Kingdom". In Bárta, Miroslav; Coppens, Filip; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2005, Proceedings of the Conference held in Prague (June 27–July 5, 2005). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 311–341. ISBN 978-80-7308-116-4.

- Nuzzolo, Massimilano (2007). "Sun Temples and Kingship in the Ancient Egyptian Kingdom". In Goyon, Jean Claude; Cardin, Christine. Actes Du Neuvième Congrès International Des Égyptologues, Grenoble 6-12 September 2004. Orientalia Lovaniensia analecta. 150. Leuven, Dudley: Peeters. pp. 1401–1410. ISBN 978-9-04-291717-0.

- Petrie, Flinders (1897). A history of Egypt. Volume I: From the earliest times to the XVIth dynasty (third ed.). London: Methuen & Co. OCLC 493045619.

- Petrie, Flinders (1917). Scarabs and cylinders with names: illustrated by the Egyptian collection in University College, London (PDF). London: British School of Archaeology in Egypt, University College: Bernard Quaritch. OCLC 55858240.

- Quirke, Stephen (2001). The cult of Ra : sun-worship in ancient Egypt. New York: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-005107-8.

- Rice, Michael (1999). Who is who in Ancient Egypt. London & New York: Routledge. ISBN 978-0-203-44328-6.

- "Sahure's Causeway". Archaeogate Egittologia. Archived from the original on July 16, 2011. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- Sethe, Kurt Heinrich (1903). Urkunden des Alten Reichs (in German). wikipedia entry: Urkunden des Alten Reichs. Leipzig: J.C. Hinrichs. OCLC 846318602.

- Stadelmann, Rainer (2007). "Der Kopf des Userkaf aus dem "Taltempel" des Sonnenheiligtums in Abusir". Sokar (in German). 15: 56–61.

- Strudwick, Nigel (1985). The Administration of Egypt in the Old Kingdom: The Highest Titles and Their Holders (PDF). Studies in Egyptology. London; Boston: Kegan Paul International. ISBN 978-0-7103-0107-9.

- Strudwick, Nigel C. (2005). Texts from the Pyramid Age. Writings from the Ancient World (book 16). Atlanta: Society of Biblical Literature. ISBN 978-1-58983-680-8.

- "Userkaf". Digital Egypt. Retrieved August 11, 2018.

- "Userkaf". Encyclopædia Britannica. 20 July 1998. Retrieved 11 August 2018.

- Verner, Miroslav (1980a). "Excavations at Abusir". Zeitschrift für Ägyptische Sprache und Altertumskunde. 107. pp. 158–169.

- Verner, Miroslav; Zemina, Milan (1994). Forgotten pharaohs, lost pyramids: Abusir (PDF). Prague: Academia Škodaexport. ISBN 978-80-200-0022-4. Archived from the original on 2011-02-01.

- Verner, Miroslav (1998). Die Pyramiden. Reinbek bei Hamburg: Rowohlt. ISBN 978-3-49-807062-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2000). "Who was Shepseskara, and when did he reign?". In Bárta, Miroslav; Krejčí, Jaromír. Abusir and Saqqara in the Year 2000 (PDF). Prague: Academy of Sciences of the Czech Republic, Oriental Institute. pp. 581–602. ISBN 978-80-85425-39-0. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-02-01.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001a). "Archaeological Remarks on the 4th and 5th Dynasty Chronology" (PDF). Archiv Orientální. 69 (3): 363–418.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001b). "Old Kingdom: An Overview". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 2. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 585–591. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2001c). "Pyramids". In Redford, Donald B. The Oxford Encyclopedia of Ancient Egypt, Volume 3. Oxford: Oxford University Press. pp. 87–95. ISBN 978-0-19-510234-5.

- Verner, Miroslav (2002). The Pyramids: The Mystery, Culture and Science of Egypt's Great Monuments. London: Atlantic Books. ISBN 978-1-90-380945-7.

- Voß, Susanne (2004). Untersuchungen zu den Sonnenheiligtümern der 5. Dynastie. Bedeutung und Funktion eines singulären Tempeltyps im Alten Reich (PDF) (PhD). OCLC 76555360. Retrieved 11 June 2015.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1982). "Niuserre". In Helck, Wolfgang; Otto, Eberhard. Lexikon der Ägyptologie. Band IV: Megiddo - Pyramiden (in German). Wiesbaden: Harrassowitz. pp. 517–518. ISBN 978-3-447-02262-0.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1997). Chronologie des pharaonischen Ägypten: die Zeitbestimmung der ägyptischen Geschichte von der Vorzeit bis 332 v. Chr. Münchner Ägyptologische Studien. 46. Mainz am Rhein: Verlag Philipp von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-80-532310-9.

- von Beckerath, Jürgen (1999). Handbuch der ägyptischen Königsnamen. Münchner ägyptologische Studien (in German). 49. Mainz: Philip von Zabern. ISBN 978-3-8053-2591-2.

- Waddell, William Gillan (1971). Manetho. Loeb classical library, 350. Cambridge, Massachusetts; London: Harvard University Press; W. Heinemann. OCLC 6246102.

- Wildung, Dietrich (1969). Die Rolle ägyptischer Könige im Bewußtsein ihrer Nachwelt. Teil I. Posthume Quellen über die Könige der ersten vier Dynastien. Münchener Ägyptologische Studien (in German). 17. München, Berlin: Deutscher Kunstverlag. OCLC 698531851.

- Wilkinson, Richard (2000). The complete temples of ancient Egypt. London: Thames & Hudson. ISBN 978-0-50-005100-9.

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Userkaf. |

| Preceded by Shepseskaf or Djedefptah |

Pharaoh of Egypt Fifth Dynasty |

Succeeded by Sahure |