Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes

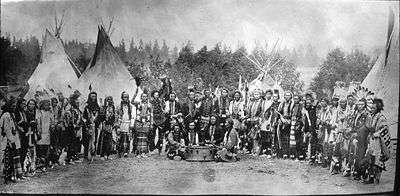

The Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation are a federally recognized tribe in the U.S. state of Montana. The government includes members of several Bitterroot Salish, Kutenai and Pend d'Oreilles tribes and is centered on the Flathead Indian Reservation

The peoples of this area were named Flathead Indians by Europeans who came to the area. The name was originally applied to various Salish peoples, based on the practice of artificial cranial deformation by some of the groups, though the modern groups associated with the Flathead Reservation never engaged in it.

Early days of the Salish

The Salis (Flatheads) initially lived entirely east of the Continental Divide but established their headquarters near the eastern slope of the Rocky Mountains. Occasionally, hunting parties went west of the Continental Divide but not west of the Bitterroot Range. The easternmost edge of their ancestral hunting forays were the Gallatin Range, Crazy Mountain, and Little Belt Ranges.

Early territory

The Flathead and the Pend d'Oreille both agree that the Flathead once occupied a large territory on the plains east of the Rocky Mountains. This tribal homeland included the present-day counties of Broadwater, Jefferson, Deer Lodge, Silver Bow, Madison and Gallatin and parts of Lewis & Clark, Meagher and Park. This was about the time, when they got the first horses.[1]:303–304

The tribe consisted of at least four bands. Respectively, they had winter quarters near present-day Helena, near Butte, east of Butte and in the Big Hole Valley.[1]:309

Nearby peoples

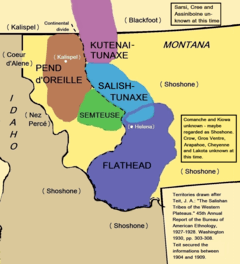

Right north of the Flathead lived the Salis-Tunaxe. There was no sharp line between the two tribal territories, and the people in the border zone often intermarried. Further north lived the Kutenai-Tunaxe (Kootenai-Tunaxe). Next to them lived the Salisan tribes' common enemy, the Blackfoot. West of the Rocky Mountains held the Pend d'Oreille the territory around Flathead Lake, and south of them occupied the Semteuse a relatively small area. The numerous Shoshone semi-surrounded the Salish from northeast to southwest.[1]:304 It seems the Salish did not know the Comanche and Kiowa at his time. They may have been regarded as bands of Shoshone.[1]:317

Later well-established plains tribes like the Sarsi, Assiniboine, Cree, Crow, Gros Ventre, Arapaho, Cheyenne and Sioux lived far away. They were unknown to the Salish.[1]:304 and 321.

Horses - and the changed life of the Salis

The Salish got horses from the Shoshone,[1]:350 and the animal changed the life of the people. During dog days, the Salis paid no special attention to the buffalo.[1]:345 It was hunted just like deer and elk. Newly acquired mounts made it possible to overtake the buffalo and the secured meat and skins could easily be carried by packhorses. All other game lost in importance.

Before the horse life, the Salis lived in conical tents covered with two to four layers of sewed tule mats, depending on the season.[1]:332 The tipi soon substituted the old lodge. Instead of rawhide bags of many shapes and sizes, the women made parfleches from now on.[1]:327

Forced west of the divide

Both the Salish-Tunaxe and the Semteuse were almost "killed off in wars" with the Blackfoot[1]:317 and further reduced by smallpox.[1]:312 Some of the survivors took refuge among the Salish. With the near extinction of the Salish-Tunaxe, the Salish extended their hunting grounds northward to Sun River. Between 1700 and 1750, they were driven back by pedestrian Blackfoot warriors armed with fire weapons.[1]:316 Finally, they were forced out of the bison range and west of the divide along with the Kutenai-Tunaxe.[1]:318

History

The Flatheads lived now between the Cascade Range and Rocky Mountains. The first written record of the tribes is from their meeting with the Lewis and Clark Expedition (September 4,[2] 1805). Lewis and Clark came there and asked for horses but eventually ate the horses due to starvation. The Flatheads also appear in the records of the Roman Catholic Church at St. Louis, Missouri, to which they sent four delegations to request missionaries (or "Black Robes") to minister to the tribe. Their request was finally granted, and a number of missionaries, including Pierre-Jean De Smet, S.J., were eventually sent. The Flatheads are also located in Sula, Montana.

The tribes negotiated the Hellgate treaty with the United States in 1855. From the start, treaty negotiations were plagued by serious translation problems. A Jesuit observer, Father Adrian Hoecken, said that the translations were so poor that "not a tenth of what was said was understood by either side." But as in the meeting with Lewis and Clark, the pervasive cross-cultural miscommunication ran even deeper than problems of language and translation. Tribal people came to the meeting assuming they were going to formalize an already-recognized friendship. Non-Indians came with the goal of making official their claims to native lands and resources. Isaac Stevens, the new governor and superintendent of Indian affairs for the Washington Territory, was intent on obtaining cession of the Bitterroot Valley from the Salish. Many non-Indians were already well aware of the valley's potential value for agriculture and its relatively temperate climate in winter. Because of the resistance of Chief Victor (Many Horses), Stevens ended up inserting into the treaty complicated (and doubtless poorly translated) language that defined the Bitterroot Valley south of Lolo Creek as a "conditional reservation" for the Salish. Victor put his X mark on the document, convinced that the agreement would not require his people to leave their homeland. No other word came from the government for the next fifteen years, so the Salish assumed that they would indeed stay in their Bitterroot Valley forever.

After the 1864 gold rush in the newly established Montana Territory, pressure upon the Salish intensified from both illegal non-Indian squatters and government officials. In 1870, Victor died, and he was succeeded as chief by his son, Chief Charlot (aka Charlo, Claw of the Little Grizzly). Like his father, Charlot adhered to a policy of nonviolent resistance. He insisted on the right of his people to remain in the Bitterroot Valley. But territorial citizens and officials thought the new chief could be pressured into capitulating. In 1871, they successfully lobbied President Ulysses S. Grant to declare that the survey required by the treaty had been conducted and that it had found that the Jocko (Flathead) Reservation was better suited to the needs of the Salish. On the basis of Grant's executive order, Congress sent a delegation, led by future president James Garfield, to make arrangements with the tribe for their removal. Charlot ignored their demands and even their threats of bloodshed, and he again refused to sign any agreement to leave. U.S. officials then simply forged Charlot's "X" onto the official copy of the agreement that was sent to the Senate for ratification.

Over time, the real reason for the Hellgate treaty meetings became clear to the Salish and Pend d'Oreille people. Under the terms spelled out in the written document, the tribes ceded to the United States more than twenty million acres (81,000 km²) of land and reserved from cession about 1.3 million acres (5300 km²), thus forming the Jocko or Flathead Indian Reservation. Conditions had become intolerable for the Salish by the late 1880s, after the Missoula and Bitter Root Valley Railroad was constructed directly through the tribe's lands, with neither permission from the native owners nor payment to them. Charlot finally signed an agreement to leave the Bitterroot Valley in November 1889. Inaction by Congress, however, delayed the removal for another two years, and according to some observers, the tribe's desperation reached a level of outright starvation. In October 1891, a contingent of troops from Fort Missoula forced Charlot and the Salish out of the Bitterroot and roughly marched the small band sixty miles to the Flathead Reservation.

The three main tribes moved to the Flathead Reservation were the Bitterroot Salish, the Pend d'Oreille, and the Kootenai. The Bitterroot Salish and the Pend d'Oreille tribes spoke dialects of the same Salish language.

A dispute over off-reservation hunting between a band of Pend d'Oreilles and the state of Montana's Fish and Game department resulted in the Swan Valley Massacre of 1908.

Though marked for termination in 1953 under the House concurrent resolution 108[3] of the US federal Indian termination policy, the Flathead Tribes were able to resist the government's plans to terminate their tribal relationship in Congressional hearings in 1954.[4]

Demographics

The tribe has about 6800 members with approximately 4,000 tribal members living on the Flathead Reservation as of 2013, and 2,800 tribal members living off the reservation. Their predominant religion is Roman Catholicism. 1,100 Native Americans from other tribes and more than 10,000 non-Native Americans also live on the reservation.

Politics

As the first to organize a tribal government under the 1934 Indian Reorganization Act, the tribes are governed by a tribal council. The Tribal Council has ten members, and the council elects from within a Chairman, Vice Chairman, Secretary and Treasurer. The tribal government offers a number of services to tribal members and is the chief employer on the reservation. The tribes operate a tribal college, the Salish Kootenai College, and a heritage museum called "The People's Center" in Pablo, seat of the tribal government.

Economy

The tribes are the biggest employer on the reservation. In 2011, they provided 65% of all jobs.[5] [6]

The tribes own and jointly operate a valuable hydropower dam, called Séliš Ksanka Ql'ispé Dam (formerly known as Kerr Dam). They are the first Indian nation in the United States owning a hydroelectric dam. CSKT also operates the only local electricity provider Mission Valley Power, as well as S&K Electronics (founded 1984),[7] and the internationally operating S&K Technologies (founded 1999).[8] Other tribal businesses are the KwaTaqNuk Resort & Casino in Polson (county seat of Lake County and most populous community on the reservation) and Gray Wolf Peak Casino in Evaro, Montana.

Geography

Aboriginal lands

The peoples of these tribes originally lived in the areas of Montana, parts of Idaho, British Columbia (Canada) and Wyoming. The original territory comprised about 22 million acres (89,000 km²) at the time of the 1855 Hellgate treaty.

Reservation lands

The Flathead Reservation in northwest Montana is over 1.3 million acres (5,300 km²) in size.

The Tribal Council represents eight districts:

- Arlee District

- Dixon District

- Elmo District

- Hot Springs District

- Pablo District

- Polson District

- Ronan District

- St. Ignatius District

During World War II, a 422-foot (129 m) Liberty Ship, the SS Chief Charlot, was named in his honor and built in Richmond, California, in 1943.

Culture

- Languages

- Historical Sites

- Archaeology

Notable people

- Corwin Clairmont, artist and educator

- Marvin Camel, boxer, WBC & IBF Cruiserweight Champion

- Debra Magpie Earling, author

- D'Arcy McNickle (1904 – 1977), noted writer, Native American activist and anthropologist

- Jaune Quick–to–See Smith, artist

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 Teit, James A. (1930): The Salishan Tribes of the Western Plateaus. Smithsonian Institution. 45th Annual Report of the Bureau of American Ethnology. Washington.

- ↑ http://www.lewis-clark.org/article/1439

- ↑ US Statutes at Large 67:B132

- ↑ "Archived copy" (PDF). Archived from the original (PDF) on 2013-12-29. Retrieved 2014-12-19.

- ↑ CSKT: Sustainable Economic Development Study Results, September 2014

- ↑ CSKT: Sustainable Comprehensive Economic Development Strategy (pdf; 4,96 MB), Dezember 2015

- ↑ Website S&K Electronics

- ↑ Website S&K Technologies

Further reading

- Bigart, Robert, and Clarence Woodcock. In the Name of the Salish & Kootenai Nation: The 1855 Hell Gate Treaty and the Origin of the Flathead Indian Reservation. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1996. ISBN 0-295-97545-8

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. Ktunaxa Legends. Pablo, Mont: Salish Kootenai College Press, 1997. ISBN 0-295-97660-8

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes. The Salish People and the Lewis and Clark Expedition. Lincoln: University of Nebraska Press, 2005. ISBN 0-8032-4311-1

- Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Reservation. A Brief History of the Flathead Tribes. St. Ignatius, Mont: Flathead Culture Committee, Confederated Salish & Kootenai Tribes, 1979.

- Johnson, Olga Weydemeyer. Flathead and Kootenay; The Rivers, the Tribes, and the Region's Traders. Northwest historical series, 9. Glendale, Calif: A. H. Clark Co, 1969.

- Salish Kootenai College. Challenge to survive : history of the Salish tribes of the Flathead Indian Reservation (2008). Volume 1, From Time Immemorial, Traditional Life. Volume 2, Three Eagles and Grizzly Bear Looking Up Period, 1800-1840. Volume 3, Victor and Alexander Period, 1840-1870.

- Ronan, Peter (1890). Historical sketch of the Flathead Indian Nation from the year 1813-1890: embracing the history of the establishment of St. Mary's Indian Mission in the Bitter Root Valley, Mont.: with sketches of the missionary life of Father Ravalli and other early missionaries: wars of the Blackfeet and Flatheads and sketches of history, trapping and trading in the early days. Helena, MT: Journal Publishing Co. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Smead, William Henry (1905). Land of the Flatheads; a sketch of the Flathead Reservation, Montana, its past and present. Missoula, MT: Press of the Daily Missoulian. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

- Broderick, Therese (1909). The brand, a tale of the Flathead reservation. Seattle: Alice Harriman Company. Retrieved 2014-03-01.

External links

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Flathead. |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Kootenai (tribe). |

- Official site of the Confederated Tribes

- Official site of Nkwusm Salish Language Institute

- Treaty of Hellgate (1855)

- Edward S. Curtis's The North American Indian, Northwestern University, Digital Library Collections, "Kalispel", Page 51

- Flathead Indians historical and genealogical resources, Family Search