Bitterroot Salish

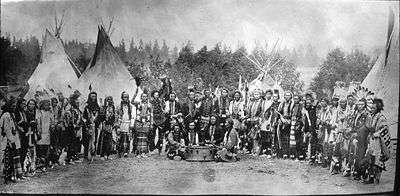

The Bitterroot Salish (or Flathead, Salish, Selish) are a Salish-speaking group of Native Americans, and one of three tribes of the Confederated Salish and Kootenai Tribes of the Flathead Nation in Montana. The Flathead Reservation is home to the Kootenai and Pend d'Oreilles tribes also. Bitterroot Salish or Flathead originally lived in an area west of Billings, Montana extending to the continental divide in the west and south of Great Falls, Montana extending to the Montana-Wyoming border.[1] From there they later moved west into the Bitterroot Valley.[2] By request, a Catholic mission was built here in 1841.[3] In 1891 they were forcibly moved to the Flathead Reservation.[4]

Alternative names

The Bitterroot Salish are known by various names including Salish, Selish, and Flathead. The name "Flathead" was a term used to identify any Native tribes who had practiced head flattening. The Salish, however, deny that their ancestors engaged in this practice. Instead, they believe that this name caught on because of the sign language which was used to identify their people: Pressing both sides of the head with your hands which meant "we the people". Supposedly, it has also been said that the reason the Bitterroot Salish had gotten the name Flathead was that, unlike the other tribes westwards, they left their heads "flat" rather than sloping them upwards at the crown of the head.[5]

Language

The people are an Interior Salish-speaking group of Native Americans. Their language is also called Salish, and is the namesake of the entire Salishan languages group. The Spokane language (npoqínišcn) spoken by the Spokane people, the Kalispel language (qlispé) spoken by the Pend d'Oreilles tribe and the Bitterroot Salish (séliš) languages are all dialects of the same language. According to Salish history, the Salish speaking people originally lived as one large nation thousands of years ago. Tribal elders say that the tribes started to break into smaller groups as the population became too big to sustain its needs in just one central location. Centuries afterward, the Salish languages had branched into different dialects from various regions the tribes dispersed to. These regions stretched from Montana all the way to the Pacific Coast. Centuries following the dispersion, the separated groups of Salishan peoples became increasingly distinct which resulted in variations on the language. The Salish language had developed into sub-families with unique languages as well as their own unique dialects. The eastern sub-family is known as Interior Salish. The three dialects within Interior Salish are Flathead (Séliš), Kalispell (Qlispé) and Spokane.[6]

History

Origins

The tribes' oral history tells of having been placed in their Indigenous homelands, which is now present-day Montana, from when Coyote killed the nałisqelixw, which literally translates into people-eaters.

Our story begins when the Creator put the animal people on this earth. He sent Coyote ahead as this world was full of evils and not yet fit for mankind. Coyote came with his brother Fox, to this big island, s the elders call this land, to free it of these evils. They were responsible for creating many geographical formations and providing good and special skills and knowledge for man to use. Coyote, however, left many faults such as greed, jealousy, hunger, envy, and many other imperfections that we know of today

— Clarence Woodcock

Within many of the Coyote stories, there are vivid descriptions relating to the history of the geological events that had occurred near the last ice age. Stories that include "the extension of glaciers down what is now Flathead Lake, the flooding of western Montana beneath a great lake, the final retreat of the bitter cold weather as the ice age came to an end, the disappearance of large animals like giant beaver and their replacement by the present-day smaller versions of those creatures". Archaeologists have been able to document a continuous occupancy within some sites as far back as 12,600 years ago during the final retreat of the glaciers. Some stories suggest that occupancy can go far back as 40,000 years when the ice age had already begun.[7]

Flathead Reservation

In 1855, Isaac Steven, the Governor and Superintendent of Indian Affairs for Washington Territory met with Xweɫxƛ̣ ̓cín (Many Horses or Victor), the head chief of the Salish; Tmɫxƛ̣ ̓cín (No Horses or Alexander), the head chief of the Pend d'Oreille; and Michelle the head chief of the Kootenais. The meeting took place in present-day Missoula, Montana. The tribal leaders were told that Stevens had wanted to talk about a peace treaty, however, the chiefs and headmen were both surprised and angered to have found out that the primary purpose was to discuss formal ownership over Indian lands. Similar to other negotiations with Northwest tribes, Stevens' goal was to concentrate numerous tribes within a single reservation, therefore making way for white settlement on as much land as possible. Despite the pressure the tribes had faced, they refused to change their minds.[8]

Because Chief Xweɫxƛ̣ ̓cín had refused to relinquish the Bitterroot Valley, Stevens inserted Article 11 within the Hellgate Treaty, which would have designated approximately 1.7 million acres in the Bitterroot Valley as a second reservation. However, within the fine print, it states that survey authorized by the president would have to determine whether the Bitterroot reservation or the Flathead Reservation would be "better adapted to the wants of the Flathead tribe.". The survey, however, was never conducted while the U.S. and Montana Territory officials failed to uphold Article 11 which was to prevent white settlement in the Bitterroot Valley before the matter had been decided. This set forth a complicated scenario for the Bitterroot Valley, as the Salish still resisted relinquishing their ancestral lands.

After the death of Chief Xweɫxƛ̣ ̓cín in 1870, Victor's son Sɫm̓xẹ Q̓woxq̣eys (Claw of the Small Grizzly Bear or Charlo) was chosen as the next chief. White settlers and Montana's territorial delegate saw this transition of leadership as an opportunity to force the Salish out to Flathead reservation. They had gotten President Grant to falsely state that the survey required in Article 11 or the Hellgate Treaty had already been completed and that it was determined that the Salish would be moved to the Flathead Reservation. In 1872, President Garfield was sent to negotiate the removal of the Salish, but when Chief Sɫm̓xẹ Q̓woxq̣eys had refused, he decided to " proceed with the work in the same manner as though Charlo [Xweɫxƛ̣ ̓cín], first chief, had signed the contract." under the assumption that the Salish will change their mind. Although the original field copy of the agreement, which remains in the National Archives to this day, has no "x" besides Xweɫxƛ̣ ̓cín's name, the official copies that Congress had voted on had an "x" by his name. This only enraged Xweɫxƛ̣ ̓cín and the tribe and strengthen their resolve to not leave the Bitterroot Valley, despite declining conditions. However, in 1891, both the government and the army had forced the removal of the Salish from the Bitterroot to the Flathead Reservation. Some historians have nicknamed this event Montana's Trail of Tears.[9]

Notes

- ↑ Carling I. Malouf. (1998). "Flathead and Pend d'Oreille". pp. 297-298.

- ↑ Carling I. Malouf. (1998). "Flathead and Pend d'Oreille". pp. 302.

- ↑ Baumler, Ellen: A Cross in the Wilderness. St. Mary's Mission elebraes 175 Years. Montana, The Magazine of Western History. Vol. 66, No. 1 (Spring 2016), pp. 18-38, sources pp. 92-93.

- ↑ Carling I. Malouf. (1998). "Flathead and Pend d'Oreille". pp. 308.

- ↑ Ruby, Robert H.; Brown,, John A.; Kinkade, Cary C. Collins ; foreword by Clifford Trafzer ; pronunciations of Pacific Northwest tribal names by M. Dale (2010). A guide to the Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest (3rd ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. p. 121. ISBN 0806140240.

- ↑ Division of Indian Education. Montana Indians Their History and Location (PDF). Helena, Montana: Montana Office of Public Instruction. p. 26. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Division of Indian Education. Montana Indians Their History and Location (PDF). Helena, Montana: Montana Office of Public Instruction. p. 25. Retrieved March 15, 2018.

- ↑ Division of Indian Education. Montana Indians Their History and Location (PDF). Helena, Montana: Montana Office of Public Instruction. p. 30. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

- ↑ Division of Indian Education. Montana Indians Their History and Location (PDF). Helena, Montana: Montana Office of Public Instruction. p. 31. Retrieved March 17, 2018.

References

- Carling I. Malouf. (1998). "Flathead and Pend d'Oreille". In Sturtevant, W.C.; Walker, D.E. "Handbook of North American Indians, V. 12, Plateau.". Washington: Government Printing Office, Smithsonian Institution.

- Ruby, Robert H.; Brown,, John A.; Kinkade, Cary C. Collins ; foreword by Clifford Trafzer ; pronunciations of Pacific Northwest tribal names by M. Dale (2010). A guide to the Indian tribes of the Pacific Northwest (3rd ed. ed.). Norman: University of Oklahoma Press. ISBN 0806140240

- Division of Indian Education. Montana Indians Their History and Location (PDF). Helena, Montana: Montana Office of Public Instruction.