United Kingdom constitutional law

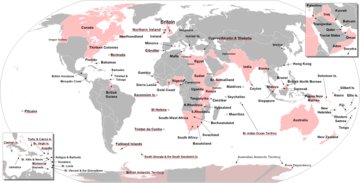

United Kingdom constitutional law concerns the political governance of the United Kingdom of Great Britain and Northern Ireland. As one of the oldest continuous political systems on earth, the UK constitution has never been written into a single code, but principles have emerged over the centuries. The Magna Carta 1215, forced the King to free the church from the state, to call "common counsel" or Parliament, hold courts in a fixed place, a fair trial, free movement of people to trade, and to give commoners rights to use the land.[2] By the Bill of Rights 1689, Parliament had finally won supremacy over the church, the courts, and the King, and said that the 'election of members of Parliament ought to be free'. By the Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928, every adult man and woman was finally entitled to vote for Parliament. The UK was a founding member of the International Labour Organisation, the United Nations, the Commonwealth, the Council of Europe, the European Union, and the World Trade Organisation.[3] Parliamentary sovereignty, the rule of law, democracy, and internationalism, have consistently guided the UK's political system to advance the social and economic development of its people.

History

- King Aethelberht (600 AD) and Witenagamot

- William the Conqueror, Norman Invasion (1066)

- Magna Carta 1215 signed at Runnymede, First Barons' Revolt under King John

- Crusades and Robin Hood

- Charter of the Forest 1217 signed at St Paul's

- Black Death of 1348

- Peasants' Revolt 1381

- Law in Wales Act 1535 (27 Hen VIII c 26)

- Calvin's case (1608) 7 Co Rep 1a, people born in England and Scotland after union owed allegiance to the same King, after the union of the crowns under James I of England or James VI of Scotland upon death of Elizabeth I in 1603.

- Petition of Right 1628 (3 Car 1 c 1) against taxation without consent of Parliament, arbitrary imprisonment, commissions of martial law in times of peace, billeting of soldiers upon private persons.

- English Civil War (1642–1651)

- Charles I of England executed in 1649

- Restoration of Charles II of England, James II of England ousted in Glorious Revolution, for William and Mary of Orange. Conflict ended at Battle of the Boyne

- Bill of Rights 1688 and Claim of Right Act 1689 in Scotland

- J Locke, Second Treatise on Government (1689)

- Act of Settlement 1700, Crown Anglican, no Member of Commons paid by Crown, judicial salaries

- Act of Union 1707, England and Scotland become Great Britain, Scottish representation at Westminster, Scots private law and courts continue

- 1715 and 1745, Jacobite risings

- South Sea Bubble of 1720, first stock market collapse

- Robert Walpole, considered first "Prime Minister" (1721-1742)

- Baron de Montesquieu, The Spirit of the Laws (1748)

- American Revolution 1776

- First Fleet to Australia 1787

- Union with Ireland Act 1800

- 1829, Catholic emancipation

- Chartism. Great Reform Act 1832

- Representation of the People Act 1867

- W Bagehot, The English Constitution (1867)

- AV Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (3rd edn 1889)

- People's Budget

- Trade Disputes Act 1906, Old Age Pensions Act 1908, National Insurance Act 1911

- Parliament Act 1911, crisis of Lords, when they refused to pass a Finance Bill.

- Representation of the People Act 1918

- Suffragettes

- Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928

- Government of Ireland Act 1920

- Imperial Conference 1926, declared the Commonwealth of Nations and that all dominions had equal status (at least formally) in the British Empire

- Edward VIII of England abdication crisis in 1936

- Indian Independence 1948

- Belfast or Good Friday Agreement (10 April 1998)

- Scotland Act 1998

- Northern Ireland Act 1998

- Government of Wales Act 2006

- Ministerial Code (2010)

- Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011

- European Union (Withdrawal) Bill

Principles

While the United Kingdom's constitution has not been codified into a single document, like the Constitution of South Africa or the Grundgesetz in Germany, general principles run through the law.[6] The main sources of law, which compose the UK constitution (or "constitute" the body politic) are Acts of Parliament, cases decided by courts, and conventions on how the Cabinet, the Prime Minister, Parliament or the Monarch conduct themselves.[7] Through legislation, case law and conventions, at least four main principles are usually recognised. First, parliamentary sovereignty is a foundational principle. Through the English Reformation, the Civil War, the Glorious Revolution of 1689 and the Act of the Union 1707, Parliament became the dominant source of law, above the judiciary, executive, monarchy, or church. Parliamentary sovereignty means Parliament can make or unmake any law, a fact that is usually justified by Parliament upholding other principles, namely the rule of law, democracy, and internationalism. Second, the rule of law has run through the constitution since the Magna Carta 1215 and Petition of Right 1628. This means the government may only conduct itself according to legal authority, including respect for human rights.[8] Third, at least since 1928, democracy has become a fundamental constitutional principle. Originally only wealthy, property-owning men held rights to vote for the House of Commons, while the King or a hereditary House of Lords dominated politics. But from 1832 adult citizens slowly won the right to universal suffrage.[9] Fourth, the UK constitution is international: Parliament has consistently integrated and augmented its practical power through its membership in international organisations, including the International Labour Organisation,[10] the United Nations, the European Convention on Human Rights, the European Union, the World Trade Organisation, and the International Criminal Court, although EU law membership was challenged by the 2016 Brexit referendum.

Parliamentary sovereignty

- AV Dicey

- R (Jackson) v Attorney General [2005] UKHL 56, [120] 'Parliamentary sovereignty is an empty principle if legislation is passed which is so absurd or so unacceptable that the populace at large refuses to recognise it as law'.

- R (HS2 Action Alliance Limited) v Secretary of State for Transport [2014] UKSC 3

- Miller v Secretary of State for Exiting the EU [2017] UKSC 5

- Leslie Stephen, The Science of Ethics (1882) 145, "Lawyers are apt to speak as though the legislature were omnipotent, as they do not require to go beyond its decisions. It is, of course, omnipotent in the sense that it can make whatever laws it pleases, inasmuch as a law means any rule which has been made by the legislature. But from the scientific point of view, the power of the legislature is of course strictly limited. It is limited, so to speak, both from within and from without; from within, because the legislature is the product of a certain social condition, and determined by whatever determines the society; and from without, because the power of imposing laws is dependent upon the instinct of subordination, which is itself limited. If a legislature decided that all blue-eyed babies should be murdered, the preservation of blue-eyed babies would be illegal; but legislators must go mad before they could pass such a law, and subjects be idiotic before they could submit to it."

Rule of law

- Entick v Carrington [1765] EWHC KB J98

- A v Home Secretary [2004] UKHL 56

- Malone v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [1979] Ch 344

- R (Corner House Research) v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2008] UKHL 60, Al-Yamamah arms deal

- UNISON v Lord Chancellor [2017] UKSC 51

- R (Pierson) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [1998] AC 539

Democracy

- Ashby v White (1703) 2 Ld Raym 938

- Morgan v Simpson [1975] QB 151

- Animal Defenders International v United Kingdom [2008] UKHL 15, [2013] ECHR 362

.jpg)

- Madzimbamuto v Lardner-Burke [1968] UKPC 18, Rhodesia independence and Parliamentary sovereignty

- Local Government Act 1972

- Scotland Act 1998

- Northern Ireland Act 1998

- Belfast or Good Friday Agreement (10 April 1998)

- Greater London Authority Act 1999

- Government of Wales Act 2006

- Gorringe v Calderdale Metropolitan Borough Council [2004] UKHL 15, it was "necessary" to view negligence in the context of "the contours of our social welfare state."

- O'Rourke v Camden London Borough Council [1998] AC 188, "the [Housing] Act [1985] is a scheme of social welfare, intended to confer benefits at the public expense on grounds of public policy."

Internationalism

- Magna Carta 1215

- Lord Mansfield

- R v Lyons [2002] UKHL 44, Lord Hoffmann, [27] 'Of course there is a strong presumption in favour of interpreting English law (whether common law or statute) in a way which does not place the United Kingdom in breach of an international obligation.

- United Nations Act 1946

- World Trade Organisation and The World Trade Organisation (Immunities and Privileges) Order 1995

- International Criminal Court Act 2001

- Comprehensive Economic and Trade Agreement (Canada-EU)

.jpg)

- European Communities Act 1972 (UK) and EU law

- R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2017] UKSC 5

- European Union (Notification of Withdrawal) Act 2017 s 1, power to PM to notify intention to negotiate to leave the EU

- European Convention on Human Rights 1950

- Human Rights Act 1998

- Vienna Convention on the Law of Treaties 1969

- Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 s 20, a treaty is ratified if 21 days pass and neither House resolves against it (3) exceptional circumstances can stop Parliament having a say. s 23, rules for EU treaties.

Institutions

Parliament

- Representation of the People Act 1983 ss 1-8

- Hirst v United Kingdom (No 2) [2005] ECHR 681

- Electoral Registration and Administration Act 2013 ss 1-5

- Ashby v White (1703) 2 Ld Raym 938

- Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 s 1(3)

- Parliamentary Constituencies Act 1986, Boundary Commission and reviews

- R (McWhirter) v Home Secretary (21 October 1969) The Times, elector in Enfield sought mandamus ('we command') to require Home Secretary to perform statutory duty of laying before Parliament Commission reports with draft orders in Council.

- Sixth Periodic Review of Westminster constituencies

- Animal Defenders International v United Kingdom [2008] UKHL 15, [2013] ECHR 362

- Political Parties, Elections and Referendums Act 2000 ss 12-69 and 149, registration of parties and donations of £7,500 nationally or £1,500 locally have to be reported to Electoral Commission

- R (Electoral Commission) v City of Westminster Magistrate's Court and UKIP [2010] UKSC 40, forfeiture of £349,216 donations by a non-UK resident

- PPERA 2000 ss 72-131 and Schs 8-13, £20m national campaign limit for elections, plus around £10,000 per constituency. Third parties £5000, but must be registered. Referendum limits, £600k funding for each side. Spending above £500 by third parties must be disclosed.

- Representation of the People Act 1983 ss 71-115, limit on national campaigns and third parties.

- Communications Act 2003 ss 319-333, political ads prohibited, apart from free party political ad slots

- Trading with the Enemy Act 1939 (c 89) ss 1-2, seven years prison for trading with an enemy who is "at war with His majesty"

- House of Commons Disqualification Act 1957 and House of Commons Disqualification Act 1975

- Ministerial and Other Salaries Act 1975 ss 1-2

- Appellate Jurisdiction Act 1876

- Life Peerages Act 1958

- House of Lords Act 1999 ss 1-2

- Constitutional Reform Act 2005 s 24

- Re Parliamentary Election for Bristol South East [1964] 2 QB 257, Viscount Stansgate or Tony Benn challenged the law disqualifying peers standing for Parliament.

- Bill of Rights 1689 art 4 said levying money for Crown without Parliament was illegal.

- Supply and Appropriation (Anticipation and Adjustments) Bill

- Supply and Appropriation (Main Estimates) Bill

- HC Modernisation Committee (2001-2) HC 1168, recommended publishing draft bills, and (2005-6) HC 1097, 'one of the most successful Parliamentary innovations of the last ten years' and 'should become more widespread'

- Parliamentary Committees of the United Kingdom

- Parliament Act 1911 ss 1-3

- Parliament Act 1949

Judiciary

- Constitutional Reform Act 2005 ss 3, 25-27A, 40, 63-79, 137A

- Judicial Appointments Regulations 2013 (SI 2192)

- Judicial Appointments Commission

- Sub judice

- Contempt of Court Act 1981

- Inquiries Act 2005

- Lord Chancellor

- Ministry of Justice

- Crown Prosecution Service

- Attorney General

Executive

- Prohibitions del Roy (1607) 12 Co Rep 63

- Petition of Right 1628 and Habeas Corpus Act 1640

- Crown Estate Act 1961, Monarch and spending

- Sovereign Grant Act 2011

- Fixed-term Parliaments Act 2011 ss 1-2

- R (Lain) v Criminal Injuries Compensation Board [1967] 2 QB 864, limits of royal prerogative

- Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 ss 20-23

- Lord Advocate v Dumbarton Council [1990] AC 580

- R (Northumbria Police Authority) v Home Secretary [1989] QB 26

- Burmah Oil Co Ltd v Lord Advocate [1965] AC 75

- Attorney-General v De Keyser's Royal Hotel [1920] AC 508

- R (Bancoult) v Foreign Secretary (No 2) [2008] UKHL 61

- Rahmatullah v Foreign Secretary [2012] UKSC 48

- R (Miller) v Secretary of State for Exiting the European Union [2017] UKSC 5

- Prime Minister of the UK

- Chequers Estate Act 1917, Chevening Estate Act 1959, Ministerial and other Pensions and Salaries Act 1991

- Public Appointments Order in Council 2013

- Cabinet of the UK

- Ministerial Code 2010

- AG v Jonathan Cape Ltd [1976] QB 752

- Ministers of the Crown Act 1975

- Civil Service (UK)

- Constitutional Reform and Governance Act 2010 s 3

- Osmotherly Rules

- Civil Service Commissioners (United Kingdom)

- Freedom of Information Act 2000 ss 1-77 and Sch 1

- BBC v Information Commissioner [2009] UKHL 9

- Sugar v BBC [2012] UKSC 4

Public services

- UK tax law

- European Social Charter 1961

- Social Security Contributions and Benefits Act 1992

- National Health Service Act 2006

- Further and Higher Education Act 1992

- Education Reform Act 1988

- Bank of England Act 1998

- Financial Services and Markets Act 2000

- Consumer Credit Act 1974

- Climate Change Act 2008

- Electricity Act 1989

- Utilities Act 2000

- Water Industry Act 1991

- Railways Act 1993

- Transport Act 1983

- Transport Act 2000

- Communications Act 2003

- Wireless Telegraphy Act 2006

- Reserve Forces Act 1996

- Armed Forces Act 2006

Administrative law

.jpg)

Administrative law, through judicial review, is an essential method to hold executive power and public bodies accountable to law. Constitutional principles often emerge through judicial review, because every public body, whose decisions affect people's lives, is created and bound by law. A person who has a "sufficient interest" can apply to the High Court,[13] within three months of the grounds of the cause of action becoming known.[14] Any public body, or private bodies exercising public functions,[15] can be the target of judicial review. A claimant can argue that a decision was unlawful in five main types of case:[16] (1) it exceeded the lawful power of the body or used its power for an improper purpose,[17] (2) violated a human right, or a legitimate expectation,[18] (3) failed to exercise relevant and independent judgement,[19] (4) acted unreasonably or disproportionately,[20] (5) exhibited bias or a conflict of interest.[21] As a remedy, a claimant can ask for the public body's decisions to be declared void, or it could ask for an injunction to prevent the body from acting unlawfully. Compensation could be payable in tort or occasionally contract.

Procedure

- Senior Courts Act 1981 s 31

- R (National Federation of Self-Employment and Small Businesses Ltd) v Inland Revenue Commissioners [1982] AC 617

- R (Equal Opportunities Commission) v Secretary of State for Employment [1995] 1 AC 1

- YL v Birmingham CC [2007] UKHL 27 (see now the Health and Social Care Act 2008 s 145)

- R (Weaver) v London and Quadrant Housing Trust [2009] EWCA Civ 587

- O'Reilly v Mackman [1983] UKHL 1, [1983] 2 AC 237

- R (Datafin plc) v Panel on Take-overs and Mergers [1987] QB 815

- R v Disciplinary Committee of the Jockey Club, ex p Aga Khan [1992] EWCA Civ 7, [1993] 1 WLR 909

- R v Inspectorate of Pollution, ex p Greenpeace Ltd (No 2) [1994] 4 All ER 329

- R v Secretary of State for the Environment, ex p Rose Theatre Trust Co Ltd [1990] 1 QB 504

- Aston Cantlow PCC v Wallbank [2003] 3 WLR 283

- Chief Constable of the North Wales Police v Evans [1982] 1 WLR 1155

Grounds for judicial review

- R (Daly) v Secretary of State for the Home Department [2001] 2 AC 532

- Huang v Home Secretary [2007] UKSC 11

- Anisminic v Foreign Compensation Commission [1969] 2 AC 147

- British Oxygen v Minister of Technology [1971] AC 610

- R v Secretary of State for Foreign Affairs, ex p World Development Movement [1995] 1 WLR 386

- R v Home Secretary ex p Venables and Thompson [1998] AC 407

- R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex p Coughlan [2001] QB 213

- R (Corner House Research) v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2008] UKHL 60

- Ahmed and others v HM Treasury [2010] UKSC 2

- Human Rights Act 1998 section 6

- Human Rights Act 1998 Schedule 1

- Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30

- Bellinger (FC) (Appellant) v Bellinger [2003] UKHL 21

- Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40

- Porter v Magill [2001] UKHL 67

- R (Alconbury) v Secretary of State for the Environment [2001] UKHL 23, [2003] 2 AC 295

- Ali v Birmingham City Council [2010] UKSC 8, [2010] 2 AC 39

- Cooper v Wandsworth Board of Works (1863) 14 CBNS 180

- R v Secretary of State for the Home Department, ex p Doody [1994] 1 AC 531

- R v Bow Street Stipendiary Magistrate, ex p Pinochet (No 2) [2000] 1 AC 119

- Runa Begum v Tower Hamlets London Borough Council [2003] UKHL 5, [2003] 2 AC 430

- R (Wright) v Secretary of State for Health [2009] UKHL 3, [2009] 1 AC 739

Public body liability

- Senior Courts Act 1981 s 31(1)

- Duncan v Cammell Laird & Co [1942] AC 624

- R (Khawaja) v Home Secretary [1984] AC 74

Human rights

- HRA 1998

- Ghaidan v Godin-Mendoza [2004] UKHL 30

- Bellinger v Bellinger [2003] UKHL 21

Liberty

- Counter-Terrorism and Security Act 2015

- Terrorism Prevention and Investigation Measures Act 2011

- Protection of Freedoms Act 2012 s 59

- Prevention of Terrorism Act 2005 s 1

- Anti-terrorism, Crime and Security Act 2001 s 23

- A v Home Secretary [2004] UKHL 56

- A v Home Secretary (No 2) [2005] UKHL 71

- Home Secretary v JJ [2007] UKHL 45

- Home Secretary v AP [2010] UKSC 24

- Gillan v United Kingdom [2009] ECHR 28

- Benjamin Franklin: people who sacrifice liberty for security will lose both, and deserve neither.

Association

- Duncan v Jones [1936] 1 KB 218

- DPP v Jones [1999] 2 AC 240

- R (Laporte) v Gloucestershire Chief Constable [2006] UKHL 55

- Austin v Metropolitan Police Commissioner [2009] UKHL 5

- Mayor of London (on behalf of the Greater London Authority) v Hall [2011] 1 WLR 504

- City of London v Samede [2012] EWCA Civ 160

See also

Notes

- ↑ Parliament Act 1911 and Parliament Act 1949

- ↑ Magna Carta 1215 clauses 1 ('... the English church shall be free...'), 12 and 14 (no tax 'unless by common counsel of our kingdom...'), 17 ('Common pleas shall... be held in some fixed place'), 39-40 ('To no one will we sell, to no one will we refuse or delay, right or justice'), 41 ('merchants shall have safe and secure exit from England, and entry to England') and 47-48 (land taken by the King 'shall forthwith be disafforested').

- ↑ The ILO was formed as part of the (now defunct) League of Nations in the Versailles Treaty 1919 Part XIII. The UN was formed in 1945. The Commonwealth of Nations was formally established by the London Declaration of 1949. The Council of Europe was created in 1950. The European Union was formed by the Maastricht Treaty 1992. The World Trade Organisation was created in 1994.

- ↑ J Froissart, Froissart's Chronicles (1385) translated by GC Macaulay (1895) 251–252. Ball went on, "What have we deserved, or why should we be kept thus in servage? We be all come from one father and one mother, Adam and Eve: whereby can they say or shew that they be greater lords than we be, saving by that they cause us to win and labour for that they dispend? They are clothed in velvet and camlet furred with grise, and we be vestured with poor cloth: they have their wines, spices and good bread, and we have the drawing out of the chaff and drink water: they dwell in fair houses, and we have the pain and travail, rain and wind in the fields; and by that that cometh of our labours they keep and maintain their estates: we be called their bondmen, and without we do readily them service, we be beaten; and we have no sovereign to whom we may complain, nor that will hear us nor do us right."

- ↑ See AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) chs 1-6

- ↑ AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018) chs 1-6

- ↑ On Conventions, see Attorney General v Jonathan Cape Ltd [1975] 3 All ER 484

- ↑ See T Bingham, The Rule of Law (2011) and Entick v Carrington [1765] EWHC KB J98

- ↑ Great Reform Act 1832 (common property qualification rules for all boroughs and counties), Representation of the People Act 1867 (extended the franchise to around 1/3 of men), Representation of the People Act 1884 (extended the male franchise), Representation of the People Act 1918 (enabled all men to vote over 21, and women over 30 with property), and Representation of the People (Equal Franchise) Act 1928 (enabled equal suffrage of men at women age 21). The Representation of the People Act 1948 further abolished multiple votes for graduates of London, Cambridge and Oxford, and other University constituencies, and the Representation of the People Act 1969 lowered voting age to 18. Restrictions on prisoner voting were inserted by the Representation of the People Act 1983. British citizens abroad can vote under the Representation of the People Act 1985, but millions of UK residents, who pay taxation but do not have citizenship, are denied representation in Parliament.

- ↑ See the Appropriation Act 1923 Sch 4

- ↑ https://www.flickr.com/photos/un_photo/24147256982

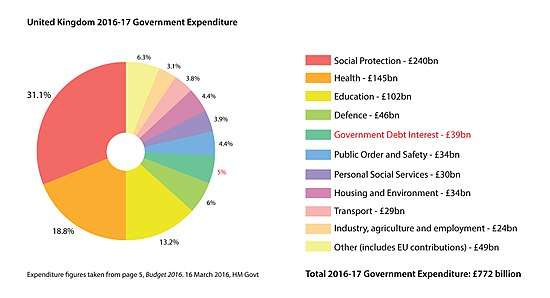

- ↑ "Budget 2016" (PDF). HM Treasury. March 2016. p. 5.

- ↑ Senior Courts Act 1981 s 31(3)

- ↑ Civil Procedure Rules rule 54.5 claims can be made up to 'three months after the grounds to make the claim first arose', but the period can be shorter if legislation says so.

- ↑ R (Datafin) v Panel on Takeovers and Mergers [1987] QB 815

- ↑ Different books and cases categorise the grounds to review administrative discretion differently, as do different fields of law such as directors' duties in UK company law, unfair dismissal in UK labour law or implied terms in English contract law. Lord Diplock in the GCHQ case said the grounds were "illegality", "irrationality" and "procedural impropriety". A Le Sueur, M Sunkin and J Murkens, Public Law Text, Cases, and Materials (3rd edn 2016) ch 16 follows this. It is often, however, unclear how a procedural requirement of the law can be separated from substance, and it was thought that "irrationality" is too restrictive. AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2014) ch 24 now suggests substantive grounds, legitimate expectations and procedural grounds. In R (Baker) v Devon CC [1995] 1 All ER 73, 88, Sir Robin Cooke said 'The administrator must act fairly, reasonably and according to law. That is the essence and the rest is mainly machinery.' M Elliott and R Thomas, Public Law (3rd edn 2017) ch 12 generally follows this. Another categorisation of Lord Bingham, Rule of Law (2010) was 'Ministers and public officers at all levels must exercise the powers conferred on them in good faith, fairly, for the purposes for which the powers were conferred, without exceeding the limits of such powers and not unreasonably.' Contrast the Companies Act 2006 ss 171-177, codifying directors' duties.

- ↑ Ridge v Baldwin [1964] AC 40 (following law). Padfield v Minister of Agriculture [1968] AC 997 (improper purpose)

- ↑ Council of Civil Service Unions v Minister for the Civil Service [1985] AC 374 (legitimate expectation rejected). R v North and East Devon Health Authority, ex p Coughlan [2001] QB 213 (legitimate expectation upheld)

- ↑ R v Home Secretary ex p Venables and Thompson [1998] AC 407 (irrelevant consideration). R (Corner House Research) v Director of the Serious Fraud Office [2008] UKHL 60 (independent judgement)

- ↑ Associated Provincial Picture Houses v Wednesbury Corporation [1948] 1 KB 223 (unreasonableness loosely defined)

- ↑ Porter v Magill [2001] UKHL 67 (bias). R v Bow Street Stipendiary Magistrate, ex p Pinochet (No 2) [2000] 1 AC 119 (possibility of a conflict of interest).

References

- Articles

- V Bogdanor, T Khaitan and S Vogenauer, 'Should Britain have a written constitution?' (2007) 78(4) Political Quarterly 499

- KD Ewing, 'The Resilience of the Political Constitution' (2013) 14(12) German Law Journal 2111

- JAW Griffith, 'The Political Constitution' (1979) 42(1) Modern Law Review 1

- F Kessler, 'Natural Law, Justice and Democracy—Some Reflections on Three Types of Thinking About Law and Justice' (1944) 19 Tulane Law Review 32

- Lord Hoffmann, (2013) 17 Oxford Law News 8-9, from a tribute at St John's Smith Square on 5 June 2013

- O Kahn-Freund, 'Autobiographical Memories of the Weimar Republic: A Conversation with Wolfgang Luthardt' (February 1978) KCL Law School Research Paper No. 2016-34

- J Laws, 'Law and Democracy' [1995] Public Law 72

- E McGaughey, 'Fascism-lite in America (or the Social Ideal of Donald Trump)' (2018) British Journal of American Legal Studies

- S Webb, 'Socialism: true and false. A lecture delivered to the Fabian Society' (21 January 1894) Fabian Tract, 51

- S Webb, 'The reform of the House of Lords' (1917) Fabian Tract, 183

- Books

- W Bagehot, The English Constitution (1867)

- Lord Bingham, Rule of Law (2010)

- AV Dicey, Introduction to the Study of the Law of the Constitution (3rd edn 1889)

- H Arendt, Eichmann in Jerusalem: A Report on the Banality of Evil (1963)

- J Froissart, Froissart's Chronicles (1385) translated by GC Macaulay (1895)

- I Jennings, A Federation for Western Europe (1940)

- J Locke, Two Treatises of Government (1689) Book II, An Essay Concerning the True Origin, Extent, and End of Civil Government

- FW Maitland, The Constitutional History of England (CUP 1919)

- JS Mill, On Liberty (1859)

- JS Mill, Considerations on Representative Government (1861)

- T More, Utopia (1516) translated by Gilbert Burnet (1901)

- FL Neumann, Behemoth: The Structure and Practice of National Socialism, 1933-1944 (1944)

- FL Neumann, The Democratic and the Authoritarian State: Essays in Political and Legal Theory (1957)

- S Webb and B Webb, Industrial Democracy (1890)

- S Webb, English Local Government (1906 through 1929) Volumes I–X

- Textbooks

- AW Bradley, KD Ewing and CJS Knight, Constitutional and Administrative Law (2018)

- A Le Sueur, M Sunkin and J Murkens, Public Law Text, Cases, and Materials (3rd edn 2016)

- M Elliott and R Thomas, Public Law (3rd edn 2017)