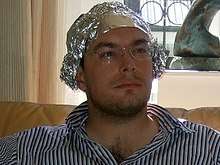

Tin foil hat

A tin foil hat is a hat made from one or more sheets of aluminium foil, or a piece of conventional headgear lined with foil, worn in the belief or hope that it shields the brain from threats such as electromagnetic fields, mind control, and mind reading. The notion of wearing homemade headgear for such protection has become a popular stereotype and byword for paranoia, persecutory delusions, and belief in pseudoscience and conspiracy theories.

Note that "tin foil" is a common misnomer for aluminium foil; packaging metal foil was formerly made out of tin before it was replaced with aluminium.[1]

Origin

An early allusion to an "insulative electrical contrivance encircling the head during thought" appears in the unusual 1909 non-fiction publication Atomic Consciousness [2] by self-proclaimed "seer" John Palfrey (aka "James Bathurst") who believed such headgear was not effective for his "retention of thoughts and ideas" against a supposed "telepathic impactive impingement".[3]

The usage of a metal foil hat for protection against interference of the mind was mentioned in a science fiction short story by Julian Huxley, "The Tissue-Culture King", first published in 1926,[4][5] in which the protagonist discovers that "caps of metal foil" can block the effects of telepathy.[6]

Some people have a belief that such hats prevent mind control by governments, spies, or paranormal beings that employ ESP or the microwave auditory effect. People in many countries who believe they are "targeted individuals" (TIs), subject to government spying or harassment, have developed websites, conference calls, and support meetings to discuss their concerns, including the idea of protective headgear.[7] Over time the term "tin foil hat" has become associated with paranoia and conspiracy theories.[8]

Scientific basis

The notion that a metal foil hat can significantly reduce the intensity of incident radio frequency radiation on the wearer's brain has some scientific validity, as the effect of strong radio waves has been documented for quite some time.[9] A well-constructed aluminum foil enclosure would approximate a Faraday cage for parts of the body enclosed by metal, reducing the amount of radio frequency electromagnetic radiation passing through to the parts of the body covered by the foil. Unlike a foil hat, a Faraday cage is a complete enclosure. A foil hat does not protect the face, and other uncovered areas of the body are not protected. A common high school physics demonstration involves placing an AM radio on aluminum foil, and then covering the radio with a metal bucket. The AM radio is completely inside a metal enclosure. This leads to a noticeable reduction in signal strength received by the AM radio. The efficiency of a metal enclosure in blocking electromagnetic radiation depends on the thickness of the foil, as dictated by the "skin depth" of the conductor for a particular wave frequency range of the radiation. For half-millimetre-thick aluminum foil, radiation above about 20 kHz (i.e., including both AM and FM bands) would be partially blocked, although aluminum foil is not sold in this thickness, so numerous layers of foil would be required to achieve this effect.[10]

A belief also exists that aluminum foil is a protective measure against the effects of electromagnetic radiation (EMR) for many unspecified EMR frequencies. Despite some allegations that EMR exposure has negative health consequences,[11] no published experimental scientific evidence has established that tinfoil hats are effective.

In 1962, Allan H. Frey discovered that the microwave auditory effect (i.e., the reception of the induced sounds by radio-frequency electromagnetic signals heard as clicks and buzzes) can be blocked by a patch of wire mesh (rather than foil) placed above the temporal lobe.[12][13]

In art and media

Foil hats have appeared in the films Signs and Futurama: Into the Wild Green Yonder.

See also

- Electromagnetic hypersensitivity

- Electromagnetic radiation and health

- Electronic harassment

- Electrophonic hearing

- Electrostatic discharge materials

- Embassy attack accusations in Cuba (and China)

- Faraday cage

- The Hum

- Microwave auditory effect

- On the Origin of the "Influencing Machine" in Schizophrenia

- Sonic weapon

References

- ↑ "Foil - metallurgy". Encyclopædia Britannica. Retrieved 17 July 2016.

- ↑ Bathurst, James (1909). Atomic Consciousness Abridgement. W. Manning, London.

- ↑ Wilson, Daniel (June 2016). "Atomic-Consciousness". Fortean Times.

- ↑ p. 118

- ↑ Huxley, Julian (1925–1926). "The Tissue-Culture King: A Parable of Modern Science". The Yale Review. XV: 479–504.

- ↑ Huxley, Julian (August 1927). "The Tissue-Culture King". Amazing Stories.

Well, we had discovered that metal was relatively impervious to the telepathic effect, and had prepared for ourselves a sort of tin pulpit, behind which we could stand while conducting experiments. This, combined with caps of metal foil, enormously reduced the effects on ourselves.

- ↑ Weinberger, Sharon (14 January 2007). "Mind Games". Washington Post. Retrieved 29 June 2015.

- ↑ "Hey Crazy--Get a New Hat". Bostonist. 15 November 2005. Archived from the original on 3 May 2007. Retrieved 5 April 2007.

- ↑ Adey, W. R. (December 1979). "Neurophysiologic effects of Radiofrequency and Microwave Radiation". Bulletin of New York Academy of Medicine. 55 (11): 1079–1093.

- ↑ Jackson, John David (1998). Classical Electrodynamics. Wiley Press. ISBN 0-471-30932-X.

- ↑ Lean, Geoffrey (7 May 2006). "Electronic smog". The Independent. London. Archived from the original on 17 May 2008. Retrieved 9 June 2009.

- ↑ Frey, Allan H. (1962-07-01). "Human auditory system response to modulated electromagnetic energy". Journal of Applied Physiology. 17 (4): 689–692. ISSN 8750-7587. PMID 13895081.

- ↑ Elder, Joe A.; Chou, C.K. (2003). "Auditory response to pulsed radiofrequency energy". Bioelectromagnetics. Wiley-Liss. 24 (S6): S162–73. doi:10.1002/bem.10163. ISSN 0197-8462. PMID 14628312.

External links