Timeline of eurypterid research

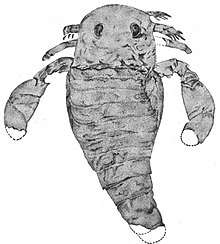

This timeline of eurypterid research is a chronologically ordered list of important fossil discoveries, controversies of interpretation, and taxonomic revisions of eurypterids, a group of extinct aquatic arthropods closely related to modern horseshoe crabs that lived during the Paleozoic Era.

The scientific study of eurypterids began in the early 19th century when James E. DeKay recognized a fossil that had previously been described as that of a fish as arthropod in nature. Though DeKay erronously believed the fossil to represent a crustacean and a missing link between trilobites and branchiopods, the fossil became the type species of first ever eurypterid to be scientifically described, Eurypterus remipes, in 1825.[1]

As of 2018, over 250 species of eurypterids have been described.[2] The most recent species to be described is Soligorskopterus tchepeliensis.[3]

19th century

1810s

1818

1820s

- James E. DeKay recognized the fossil described by Mitchill as an arthropod and named it Eurypterus remipes, the first eurypterid to be described scientifically. DeKay interpreted the animal as a crustacean and as the missing link between trilobites and branchiopods.[1]

1830s

- Louis Agassiz described the new genus Pterygotus, believing the fossils to represent a large fish. The type species is named P. problematicus.[4]

1840s

- Agassiz recognized Pterygotus as an arthropod after the discovery of more complete remains, he classified it as a crustacean of the Entomostraca subclass.[5]

1850s

- John William Salter described the new genus Himantopterus and the new species H. acumintus, H. banksii, H. bilobus, H. lanceolatus, H. maximus and H. perorntus.[6]

1880s

- Matthew described the new genus and species Bunodella horrida as a crustacean.[7]

20th century

1900s

- Charles Emerson Beecher described the new genus and species Strabops thacheri as the only Cambrian eurypterid.[8]

- Clifton J. Sarle described the new species Pterygotus monroensis and Eurypterus pittsfordensis. The new genus and species Hughmilleria socialis with the variety H. socialis var. robusta is also described.[9]

- John Mason Clarke described the new species Pterygotus otisius, Hughmilleria shawangunk, Eurypterus maria, E. myops, E. cicerops and E. cestrotus.[10]

1930s

1950s

- Kjellesvig-Waering described the new species Hughmilleria bellistriata.[12]

- Kjellesvig-Waering described the new family Hughmilleriidae, composed of Hughmilleria, Slimonia, Grossopterus, Lepidoderma, Hastimima and the new genus Salteropterus abbreviatus (formerly a species of Eurypterus), leaving the Pterygotidae monotypic.[13]

- Pirozhnikov described two new species, Rhenopterus matarakensis and R. schiraensis.[14]

1960s

- Kjellesvig-Waering described the new species Salteropterus longilabium, Pterygotus (Pterygotus) denticulatus, P. (P.) grandidentatus, P. (P.) lightbodyi, Carcinosoma harleyi and Dolichopterus bulbosus. The new genus Parahughmilleria is described with P. salteri as the type species. Hughmilleria bellistriata, H. phelpsae and Eurypterus maria are moved to this genus. The subgenus Erettopterus is regarded as a new genus and is separated into two new subgenera, E. (Erettopterus), including the new species E. (E.) brodiei, E. (E.) marstoni and E. (E.) spatulatus, and E. (Truncatiramus), including the new subspecies E. (T.) gigas megalodon. The genus Hughmilleria is splitted into two new subgenera, H. (Hughmilleria) and H. (Nanahughmilleria).[15]

- Kjellesvig-Waering and Willard P. Leutze described the new species Bassipterus virginicus (a new genus), Drepanopterus nodosus and Erettopterus (Truncatiramus) exophthalmus. The species H. (N.) phelpsae is classified as a new genus, Pittsfordipterus. Rhenopterus matarakensis is assigned to Parahughmilleria, R. schiraensis is assigned to Hughmilleria (Nanahughmilleria).[16]

1980s

- Mario Hünicken described the new genus and species Megarachne servinei as a mygalomorph spider.[17]

21st century

2000s

- Selden, Corronca and Hünicken recognized Megarachne servinei as a mycteroptid eurypterid.[18]

- Tetlie interpreted Hughmilleria banksii as a new genus, Herefordopterus. In addition, the species Hughmilleria acuminata was synonymized with Herefordopterus banksii.

2010s

- Shpinev described the new species Parahughmilleria longa and Nanahughmilleria notosibirica.[21]

- Poschmann transferred Erieopterus statzi to the genus Parahughmilleria. The new genus and species Wiedopterus noctua is described.[22]

- Lamsdell et al. described the new genus and species Pentecopterus decorahensis, the oldest eurypterid known to date.[23]

- Vrazo & Ciurca described the new ichnogenus and ichnospecies Arcuites bertiensis, interpreted as traces of a swimming eurypterid.[24]

- Plax et al. described the new genus and species Soligorskopterus tchepeliensis, to date the most recently described eurypterid genus and species.[3]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 Clarke, J. K., Ruedemann R. (1912) "The Eurypterida of New York"

- ↑ Dunlop, J. A.; Penney, D.; Jekel, D. (2015). "A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives (version 16.0)" (PDF). World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern.

- 1 2 Plax, Dmitry P.; Lamsdell, James C.; Vrazo, Matthew B.; Barbikov, Dmitry V. (2018). "A new genus of eurypterid (Chelicerata, Eurypterida) from the Upper Devonian salt deposits of Belarus". Journal of Paleontology. doi:10.1017/jpa.2018.11.

- ↑ Murchison, Roderick Impey (1839). The Silurian System, Founded on Geological Researches in the Counties of Salop, Hereford, Radnor, Montgomery, Caermarthen, Brecon, Pembroke, Monmouth, Gloucester, Worcester, and Stafford: With Descriptions of the Coalfields and Overlying Formations. Albemarle Street. p. 606.

- ↑ M'Coy, Frederick (2009). "XLI.—On the classification of some British fossil Crustacea, with notices of new forms in the University Collection at Cambridge". Annals and Magazine of Natural History. 4 (24) (24): 392–414. doi:10.1080/03745486009494858.

- ↑ Salter, John W. (1856). On some new Crustacea from the uppermost Silurian Rocks. Quarterly Journal of the Geological Society of London. 12. pp. 26–34.

- ↑ Matthew, G. F. (1889). "On some remarkable organisms of the Silurian and Devonian rocks in southern New Brunswick". Transactions of the Royal Society of Canada. 6 (4): 49–62.

- ↑ Beecher, C. E. (1901). "Discovery of Eurypterid remains in the Cambrian of Missouri". American Journal of Science. 12: 364–366. doi:10.2475/ajs.s4-12.71.364.

- ↑ Sarle, Clifton J. "A new eurypterid fauna from the base of the Salina of western New York". 69. New York State Museum Bulletin: 1080–1108.

- ↑ Clarke, John M. (1907). The Eurypterus shales of the Shawangunk Mountains in eastern New York. New York State Museum Bulletin. 107. pp. 295–310.

- ↑ Raasch, Gilbert Oscar. Cambrian Merostomata. Geological Society of America. 19. pp. 1–146. doi:10.1130/SPE19. ISBN 9780813720197.

- ↑ Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. "A New Silurian Hughmilleria from West Virginia". Journal of Paleontology. 24 (2): 226–228. JSTOR 1299503.

- ↑ Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1951). "Downtonian (Silurian) Eurypterida from Perton, near Stoke Edith, Herefordshire". Geological Magazine. 88 (1): 1–24. doi:10.1017/S0016756800068874. ISSN 1469-5081.

- ↑ Pirozhnikov, L. P. (1957). "Remains of Gigantostraca from the series of Matakara (Devonian of the North Minusinsk Depression)". Vsesojuzuoe Paleontologiceskoe Obchestvo Ezegodnik. 16: 207–213. ISSN 0201-9280. OCLC 229469975.

- ↑ Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. (1961). "The Silurian Eurypterida of the Welsh Borderland". Journal of Paleontology. 35 (4): 789–835. JSTOR 1301214.

- ↑ Kjellesvig-Waering, Erik N. "A New Silurian Hughmilleria from West Virginia". Journal of Paleontology. 24 (2): 226–228. JSTOR 1299503.

- ↑ Hünicken, Mario A. (1980). "A giant fossil spider (Megarachne servinei) from Bajo de Véliz, Upper Carboniferous, Argentina". Boletin de la Academia Nacional de Ciencias, Córdoba, Argentina. 53: 317–341.

- ↑ Selden, Paul A; Corronca, José A; Hünicken, Mario A (2005-03-22). "The true identity of the supposed giant fossil spider Megarachne". Biology Letters. 1 (1): 44–48. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2004.0272. ISSN 1744-9561. PMC 1629066. PMID 17148124.

- ↑ Erik Tetlie, Paul A Selden, Dong Ren (2007). "A new Silurian eurypterid (Arthropoda: Chelicerata) from China". Palaeontology. 50 (3): 619–625. doi:10.1111/j.1475-4983.2007.00651.x.

- ↑ Miller, Randall F.; Tetlie, O. Erik (2007). "The presumed Synziphosuran Bunodella horrida Matthew, 1889 (Silurian; Cunningham Creek Formation, New Brunswick, Canada) is a eurypterid". 81 (3): 588–590. doi:10.1666/05127.1.

- ↑ Shpinev, E. S. (2012). "On some eurypterids (Eurypterida, Chelicerata) from the Devonian of South Siberia". 46 (4): 370–377. doi:10.1134/S0031030112040119.

- ↑ Poschmann, Markus (2015-12-01). "Sea scorpions (Chelicerata, Eurypterida) from the Lower Devonian (Siegenian) of the Lahrbach Valley/Westerwald area (SW Germany, Rhineland-Palatinate)". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 89 (4): 783–793. doi:10.1007/s12542-015-0261-9. ISSN 0031-0220.

- ↑ Lamsdell, James C.; Briggs, Derek E. G.; Liu, Huaibao; Witzke, Brian J.; McKay, Robert M. (2015). "The oldest described eurypterid: a giant Middle Ordovician (Darriwilian) megalograptid from the Winneshiek Lagerstätte of Iowa". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 15: 169. doi:10.1186/s12862-015-0443-9. PMC 4556007. PMID 26324341.

- ↑ Vrazo, Matthew B.; Ciurca, Samuel J. (2017). "New trace fossil evidence for eurypterid swimming behaviour". Palaeontology. 61 (7): 1–18. doi:10.1111/pala.12336. ISSN 1475-4983.

External links