Jaekelopterus

| Jaekelopterus | |

|---|---|

| |

| Fossil of J. rhenaniae, Natural History Museum, Mainz | |

| Scientific classification | |

| Kingdom: | Animalia |

| Phylum: | Arthropoda |

| Subphylum: | Chelicerata |

| Order: | †Eurypterida |

| Superfamily: | †Pterygotioidea |

| Family: | †Pterygotidae |

| Genus: | †Jaekelopterus Waterston, 1964 |

| Type species | |

| †Jaekelopterus rhenaniae Jaekel, 1914 | |

| Species | |

| |

| Synonyms | |

| |

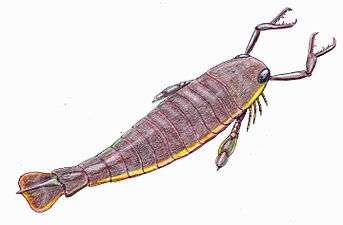

Jaekelopterus is a genus of giant predatory eurypterid, an extinct group of aquatic arthropods. Fossils of Jaekelopterus have been discovered in deposits of Early Devonian age, from the Pragian and Emsian stages, and have been referred to two known species, the type species J. rhenaniae from freshwater strata in the Rhineland and J. howelli from estuarine strata in Wyoming. The generic name is composed of a patronym honouring German paleontologist Otto Jaekel, who described the type species, and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing".

Based on the isolated fossil remains of a large chelicera (claw) from the Klerf Formation of Germany, J. rhenaniae has been estimated to have reached a size of around 2.3–2.6 metres (7.5–8.5 ft), average 2.5 metres (8.2 ft), which would make Jaekelopterus the largest known arthropod ever discovered, surpassing other large arthropods such as fellow giant eurypterids Acutiramus and Pterygotus and the giant millipede Arthropleura.

Studies on the chelicerae and compound eyes of Jaekelopterus have revealed that it was an active and powerful predator with high visual acuity and it likely represented an apex predator in the ecosystems of Early Devonian Euramerica. Although eurypterids such as Jaekelopterus are often called "sea scorpions", the strata in which Jaekelopterus has been found suggest that it dwelled in freshwater systems and estuaries, rather than in marine environments proper.

Description

Jaekelopterus is the largest known eurypterid and the largest known arthropod to ever exist. A chelicera (claw) from the Emsian Klerf Formation of Willwerath, Germany measured 36.4 centimetres (14.3 in) in length, but is missing a quarter of its length, suggesting that the full chelicera would have been 45.5 centimetres (17.9 in) long. If the proportions between body length and chelicerae match those of other giant pterygotids, such as Acutiramus and Pterygotus where the ratio between claw size and body length is relatively consistent, the specimen of Jaekelopterus that possessed the chelicera in question would have measured between 233 and 259 centimetres (7.64 and 8.50 ft) in length. With the chelicerae extended, another metre would be added to this length. This estimate exceeds the maximum body size of all other known giant arthropods by almost half a metre even if the extended chelicerae are not included.[1]

Jaekelopterus is diagnosed as a pterygotid with a triangular telson (the posteriormost segment of its body) and inclined principal denticles on its cheliceral rami,[2] similar to other pterygotids in its overall morphology.[3] This group of highly derived eurypterids differ from other groups by a number of features, perhaps most prominently in the chelicerae and the telson. The chelicerae of the Pterygotidae were enlargened and robust, clearly adapted to be used for active prey capture with chelae more similar to the claws of some modern crustaceans, with well developed teeth on the claws, than to the chelicerae of other eurypterid groups.[4] Another feature distinguishing the group from other eurypterid groups were their flattened and expanded telsons, likely used as rudders when swimming.[5] The morphology and body construction of Jaekelopterus and other eurypterids in the Pterygotidae suggests they were adapted to a completely aquatic lifestyle. Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie (2007) considered it highly unlikely that an arthropod with the size and build of Jaekelopterus would be able to walk on land.[1]

History of research

Jaekelopterus was originally described as a species of Pterygotus, P. rhenaniae, by German paleontologist Otto Jaekel based on an isolated fossil pretelson he received that had been discovered in Lower Devonian deposits of the Rhineland. Jaekel considered the pretelson to be very characteristic of Pterygotus, with other discovered elements differing very little from previously known species of Pterygotus, such as P. buffaloensis, and estimated the length of the animal in life to about 1 metre (1.5 metres if the chelicerae are included).[6]

Based on more comprehensive material discovered by Professor W. Gross near Overath, Størmer (1936)[7] provided a more comprehensive and detailed description of the species. Størmer interpreted the genital appendages as being segmented, distinct from other species of Pterygotus.[8]

Charles D. Waterston erected the genus Jaekelopterus in 1964 to accommodate Pterygotus rhenaniae, which he considered sufficiently distinct from other species of Pterygotus to warrant its own genus, primarily due to the abdominal appendages of Jaekelopterus being segmented as opposed to those of Pterygotus.[9] Waterston diagnosed Jaekelopterus as a pterygotid with segmented genital appendages, a trapezoid prosoma, narrow and long chelicerae with terminal teeth almost at right angles to the rami and the primary teeth slightly angled anteriorly and with a telson with an expanded terminal spine and dorsal keel.[9] The generic name is composed of a patronym honouring German paleontologist Otto Jaekel, who described the type species, and the Greek word πτερόν (pteron) meaning "wing", a common epithet in eurypterid names.[9]

In 1974, Størmer erected a new family to house the genus, "Jaekelopteridae", due to the supposed considerable differences between the genital appendage of Jaekelopterus and other pterygotids.[8] This diverging feature has later proven to simply represent a misinterpretation by Størmer (1936), the genital appendage of Jaekelopterus in fact being unsegmented like that of Pterygotus.[1] As such, the family Jaekelopteridae has subsequently been rejected and treated as synonymous with the family Pterygotidae.[8]

Another species of Pterygotus, "P. howelli", was named by Kjellesvig-Waering and Størmer (1952) based on fossil remains from Lower Devonian deposits in Wyoming.[10] This species was assigned to Jaekelopterus as Jaekelopterus howelli by Tetlie (2007).[4] J. howelli, known from over 30 specimens, has an almost identical pattern of denticulation on the chelicerae as J. rhenaniae and additionally preserves a flattened posterior margin of the telson, which results in a triangular shape, as in J. rhenaniae. Its serrated telson margin and the massive elongation of the second intermediate denticle clearly distinguishes it from J. rhenaniae. Furthermore, the type A genital appendage lacks median distal indentation.[2] J. howelli was significantly smaller than J. rhenaniae, reaching 80 centimetres (2.6 ft) in length.[11]

Classification

Jaekelopterus is classified within the family Pterygotidae in the superfamily Pterygotioidea.[2][1][12] Jaekelopterus is very similar to Pterygotus, virtually only distinct in features of its genital appendage and potentially its telson. The close similarities between the two genera have prompted some researchers to question if the pterygotids are oversplit on the generic level.[13] Based on some similarities in the genital appendage, it has been suggested that Jaekelopterus, Pterygotus and even Acutiramus could be synonyms of each other.[3] Though differences have been noted in chelicerae, chelicerae have been questioned as the basis of generic distinctions in eurypterids since their morphology is dependent on lifestyle and vary throughout ontogeny. Whilst telson morphology can be used to distinguish genera in eurypterids, the triangular telson of Jaekelopterus might still fall within the morphological range of the paddle-shaped telsons present in Pterygotus and Acutiramus.[3] Genital appendages can vary even within genera, for instance the genital appendage of Acutiramus changes from species to species, being spoon-shaped in earlier species and then becoming bilobed and eventually beginning to look similar to the appendage of Jaekelopterus. An inclusive phylogenetic analysis with multiple species of Acutiramus, Pterygotus and Jaekelopterus is required to resolve whether or not the genera are synonyms of each other.[3]

The cladogram below is based on the nine best-known pterygotid species and two outgroup taxa (Slimonia acuminata and Hughmilleria socialis). Jaekelopterus had previously been classified as a basal sister-taxon to the rest of the pterygotidae due to its supposedly segmented genital appendages (fused and undivided in other pterygotids), but restudy of the specimens in question revealed that the genital appendage of Jaekelopterus also was undivided. The material examined and phylogenetic analysis conducted by Braddy, Poschmann and Tetlie (2007)[1] revealed that Jaekelopterus was not a basal pterygotid, but one of the most derived taxa in the group.[1] The cladogram also contains the maximum sizes reached by the species in question, which have been suggested to possibly have been an evolutionary trait of the group per Cope’s Rule ("phyletic gigantism").[1][14]

| Pterygotioidea |

| ||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||||

Paleobiology

Gigantism

The pterygotid eurypterids contain many of the largest known eurypterids, such as Pterygotus and Acutiramus. Several factors have been suggested that might have contributed to the unprecedented large size of Jaekelopterus, its relatives and other large Paleozoic invertebrates, such as predation, courtship behaviour, competition and environment resources.[15]

Factors such as respiration, the energy costs of moulting, locomotion and the actual properties of the exoskeleton restrict the sizes that can be reached by arthropods.[1] Other than the robust and heavily sclerotized claws, most of the large body segments of the pterygotids preserve as thin and unmineralized. Even stergites and sternites (the plates that form the surfaces of the abdominal segments) are generally preserved as paper-thin compressions, suggesting that members of the group were very lightweight in construction.[1] Similar lightweight adaptations can be observed in other Paleozoic giant arthropods, such as the giant millipede-like Arthropleura, and it has been suggested to be vital for the evolution of giant arthropod sizes.[16] A lightweight build decreases the influence of factors that restrict body size.[1]

Though the largest arthropods, the lightweight build of Jaekelopterus and other giant pterygotid eurypterids meant that they likely were not the heaviest. Other giant eurypterids, particularly the deep-bodied walking forms in the Hibbertopteridae such as the almost 2 metre long Hibbertopterus, may have rivalled the pterygotids and other giant arthropods in weight, if not surpassed them.[17]

Some researchers have suggested that the massive size estimates for Jaekelopterus are exaggerated, noting that the size estimates assume that the relative proportions between the chelicerae and body length would stay the same as the animal matured. The denticles were observed as showing positive allometry, which some researchers suggest could have occurred in the chelicerae as a whole. Furthermore, the largest coxae found of the same species, measuring 27 centimetres wide,[1] only give an estimated maximum length of 180 cm.[13] However, positive allometry has not been demonstrated in eurypterid chelicerae as a whole in any other eurypterid genus, including in the closest relatives of Jaekelopterus. There are also some undescribed specimens of J. rhenaniae of similar proportions as the large chelicera, including another claw found in the same strata as the original find. Thus, the size estimates around 2.5 metres remain the most accurate estimates on the maximum size of the species yet.[18]

Ontogeny

Like all other arthropods, eurypterids matured through a sequence of stages called "instars" consisting of periods of ecdysis followed by rapid growth. Unlike many arthropods, such as insects and crustaceans, chelicerates (the group to which eurypterids like Jaekelopterus belongs) are generally direct developers, meaning that there are no extreme morphological changes after they have hatched. Extant xiphosurans hatch without the full amount of adult opisthosomal appendages (appendages attached to the opisthosoma, the posterior segments of the body), but extant spiders are fully direct developers, making it unknown if the eurypterids had developed true direct development.[2]

Though several fossilized instars of Jaekelopterus howelli are known, the fragmentary and incomplete status of the specimens make it difficult to study its ontogeny in detail. Despite this, there are some noticeable changes occurring in the chelicerae, telson and metastoma (a large plate that is part of the abdomen). Four of the J. howelli specimens studied by Lamsdell and Selden (2013) preserve the chelicerae in enough detail to allow for study of the denticles, out of which two were assumed to be juveniles and two were assumed to be adults. The morphology of the chelicerae are similar across all ages, with the same arrangement and number of denticles, but there were also some noticeable differences. Particularly, the principal denticles had grown in size relative to the intermediate denticles, being 1.5 times the size of the intermediate denticles in juveniles, but up to 3.5 times the size of the intermediate denticles in adults. Furthermore, the terminal denticle was far larger and more robust in adult specimens than in juveniles. Perhaps most extreme of all, the second intermediate denticle is not different from the other intermediate denticles in size in juveniles, but is elongated massively in adults, where it is over 2 times the length of any principal denticle.[2] Though such growth in the denticles of pterygotids has been described in other genera as well, the massive elongation of the second intermediate denticle through ontogeny is unique to Jaekelopterus, particularly to J. howelli.[2]

The metastoma of Jaekelopterus also altered its dimensions as the animal matured. In J. rhenaniae, the relative width of the metastoma decreased through ontogeny. The metastoma in J. howelli is also relatively broader in juveniles than in adults, though the length-width ratios measured in juveniles and adults were not as extreme as assumed, being 1.43 in juveniles and 1.46 in adults.[2] Such a change in metastomal dimensions has been noted in other eurypterid genera as well, such as Stoermeropterus, Moselopterus and Strobilopterus.[2]

Paleoecology

The cheliceral morphology and visual acuity of the pterygotid eurypterids separates them into distinct ecological groups. The primary method for determining visual acuity in arthropods is by determining the number of lenses in their compound eyes and the interommatidial angle (shortened as IOA and referring to the angle between the optical axes of the adjacent lenses). The IOA is especially important as it can be used to distinguish different ecological roles in arthropods, being low in modern active arthropod predators.[19]

Both Jaekelopterus rhenaniae and Pterygotus anglicus have a very high visual acuity, which researchers could determine by observing a low IOA and a large number of lenses in their compound eyes. The chelicerae of Jaekelopterus were enlarged, robust and possessed a curved free ramus and denticles of different lengths and sizes, all adaptations that correspond to strong puncturing and grasping abilities in extant scorpions and crustaceans. Some puncture wounds on the fossil of a poraspid agnathan fish from the Devonian of Utah were likely caused by Jaekelopterus. The latest research indicates that Jaekelopterus was an active and visual predator.[19] Fully grown Jaekelopterus would have been apex predators in their environments and likely preyed upon smaller arthropods (including their own kind) and early vertebrates.[1]

Further studies on the compound eyes of fossilized specimens of J. rhenaniae, including a large specimen with the right eye preserved from the uppermost Siegenian and a small and likely juvenile specimen, confirmed the high visual acuity of the genus. The overall average IOA of Jaekelopterus (0.87°), based on is comparable to that of modern predatory arthropods. The visual acuity of Jaekelopterus increased with age with smaller specimens having relatively worse eyesight.[20] This is consistent with other pterygotids, such as Acutiramus, and has been interpreted as indicating that adult Jaekelopterus lived in darker environments, such as in deeper water. Trace fossil evidence of eurypterids also supports such a conclusion, with eurypterids migrating to nearshore environments to mate and spawn.[20]

A powerful and active predator, Jaekelopterus is also noted for having been highly agile and having possessed high manoeuvrability.[21] Though not necessarily a rapidly swimming animal,[21] it was likely able to give chase to prey in habitats such as lagoons and estuaries.[20]

See also

References

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 Braddy, Simon J.; Poschmann, Markus; Tetlie, O. Erik (2007). "Giant claw reveals the largest ever arthropod". Biology Letters. 4 (1): 106–109. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2007.0491. PMC 2412931. PMID 18029297.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 James C. Lamsdell and Paul A Selden (2013). "Babes in the wood – a unique window into sea scorpion ontogeny". BMC Evolutionary Biology. 13: 98. doi:10.1186/1471-2148-13-98. PMC 3679797. PMID 23663507.

- 1 2 3 4 Lamsdell, James C.; Legg, David A. (2010/11). "An isolated pterygotid ramus (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) from the Devonian Beartooth Butte Formation, Wyoming". Journal of Paleontology. 84 (6): 1206–1208. doi:10.1666/10-040.1.

- 1 2 Tetlie, O. Erik (2007). "Distribution and dispersal history of Eurypterida (Chelicerata)" (PDF). Palaeogeography, Palaeoclimatology, Palaeoecology. 252 (3–4): 557–574. doi:10.1016/j.palaeo.2007.05.011. Archived from the original (PDF) on 2011-07-18.

- ↑ Plotnick, Roy E.; Baumiller, Tomasz K. (1988-01-01). "The pterygotid telson as a biological rudder". Lethaia. 21 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1988.tb01746.x.

- ↑ Jaekel, Otto 1914. Ein grosser Pterygotus aus dem rheinischen Unterdevon. Paläontologische Zeitschrift, 1:379–382.

- ↑ Størmer, Leif (1936). Eurypteriden aus dem Rheinischen Unterdevon (in German). Im vertrieb bei der Preussischen Geologischen Landesanstalt.

- 1 2 3 Poschmann, Markus; Tetlie, O. Erik (2006-12-01). "On the Emsian (Lower Devonian) arthropods of the Rhenish Slate Mountains: 5. Rare and poorly known eurypterids from Willwerath, Germany". Paläontologische Zeitschrift. 80 (4): 325–343. doi:10.1007/BF02990208.

- 1 2 3 D. Waterston, Charles (1964-01-01). "II.—Observations on Pterygotid Eurypterids". Transactions of the Royal Society of Edinburgh. 66 (2): 9. doi:10.1017/S0080456800023309.

- ↑ Kjellesvig-Waering, E.N.; Størmer, L. A Lower Devonian Pterygotus from Wyoming. J Paleontol. 1952;26:997–998.

- ↑ Lamsdell, James C.; Braddy, Simon J. (2009-10-14). "Cope's Rule and Romer's theory: patterns of diversity and gigantism in eurypterids and Palaeozoic vertebrates". Biology Letters: rsbl20090700. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2009.0700. ISSN 1744-9561. PMID 19828493. Supplementary information

- ↑ Dunlop, J. A., Penney, D. & Jekel, D. 2018. A summary list of fossil spiders and their relatives. In World Spider Catalog. Natural History Museum Bern

- 1 2 Kaiser, Alexander; Klok, Jaco (2008-06-23). "Do giant claws mean giant bodies? An alternative view on exaggerated scaling relationships". Biology Letters. 4 (3): 279–280. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0015. PMC 2610042. PMID 18353748.

- ↑ Gould, Gina C.; MacFadden, Bruce J. (2004-06-01). "Chapter 17: Gigantism, Dwarfism, and Cope's Rule: "Nothing in Evolution Makes Sense without a Phylogeny"". Bulletin of the American Museum of Natural History. 285: 219–237. doi:10.1206/0003-0090(2004)2852.0.CO;2 (inactive 2018-02-06).

- ↑ Briggs, D. E. G. 1985 Gigantism in Palaeozoic arthropods. Spec. Pap. Palaeontol. 33, 157.

- ↑ Kraus, O., Brauckmann, C. (2003-08-26). "Fossil giants and surviving dwarfs. Arthropleurida and Pselaphognatha (Atelocerata, Diplopoda): characters, phylogenetic relationships and construction". Verhandlungen des Naturwissenschaftlichen Vereins in Hamburg. 40.

- ↑ Tetlie, O. E. (2008). "Hallipterus excelsior, a Stylonurid (Chelicerata: Eurypterida) from the Late Devonian Catskill Delta Complex, and Its Phylogenetic Position in the Hardieopteridae". Bulletin of the Peabody Museum of Natural History. 49: 19–99. doi:10.3374/0079-032X(2008)49[19:HEASCE]2.0.CO;2.

- ↑ Braddy, Simon J.; Poschmann, Markus; Tetlie, O. Erik (2008-06-23). "Reply: giant claws and big bodies". Biology Letters. 4 (3): 281–281. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2008.0116. PMC 2610059.

- 1 2 McCoy, Victoria E.; Lamsdell, James C.; Poschmann, Markus; Anderson, Ross P.; Briggs, Derek E. G. (2015-08-01). "All the better to see you with: eyes and claws reveal the evolution of divergent ecological roles in giant pterygotid eurypterids". Biology Letters. 11 (8): 20150564. doi:10.1098/rsbl.2015.0564. PMC 4571687. PMID 26289442.

- 1 2 3 Poschmann, Markus; Schoenemann, Brigitte; McCoy, Victoria E. (2016-03-01). "Telltale eyes: the lateral visual systems of Rhenish Lower Devonian eurypterids (Arthropoda, Chelicerata) and their palaeobiological implications". Palaeontology. 59 (2): 295–304. doi:10.1111/pala.12228. ISSN 1475-4983.

- 1 2 Plotnick, Roy E.; Baumiller, Tomasz K. (1988-01-01). "The pterygotid telson as a biological rudder". Lethaia. 21 (1): 13–27. doi:10.1111/j.1502-3931.1988.tb01746.x. ISSN 1502-3931.

External links