Thomas Browne

| Sir Thomas Browne | |

|---|---|

| |

| Born |

19 October 1605 London |

| Died |

19 October 1682 (aged 77) Norwich |

| Nationality | English |

| Alma mater | Pembroke College, Oxford, University of Padua, University of Leiden |

| Known for | Religio Medici, Urne-Burial and The Garden of Cyrus, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, Christian Morals |

| Scientific career | |

| Influences | Francis Bacon, Kepler, Paracelsus, Montaigne, Athanasius Kircher, Della Porta, Arthur Dee |

| Influenced | Edward Browne (physician), Samuel Johnson, Charles Lamb, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, Thomas De Quincey, Herman Melville, William Osler, Jorge Luis Borges, W. G. Sebald, Charles Scott Sherrington[1] |

Sir Thomas Browne (/braʊn/; 19 October 1605 – 19 October 1682) was an English polymath and author of varied works which reveal his wide learning in diverse fields including science and medicine, religion and the esoteric. Browne's writings display a deep curiosity towards the natural world, influenced by the scientific revolution of Baconian enquiry. Browne's literary works are permeated by references to Classical and Biblical sources as well as the idiosyncrasies of his own personality. Although often described as suffused with melancholia, his writings are also characterised by wit and subtle humour, while his literary style is varied, according to genre, resulting in a rich, unique prose which ranges from rough notebook observations to polished Baroque eloquence.

Biography

Early life

The son of Mr Thomas Browne, a silk merchant from Upton, Cheshire, and Anne Browne, the daughter of Paul Garraway of Sussex, he was born in the parish of St Michael, Cheapside, in London on 19 October 1605.[2][3] His father died while he was still young and he was sent to school at Winchester College.[4] In 1623 Browne went to Oxford University. He graduated from Pembroke College, Oxford in 1626, after which he studied medicine at Padua and Montpellier universities, completing his studies at Leiden, where he received a medical degree in 1633. He settled in Norwich in 1637 and practiced medicine there until his death in 1682.

Literary works

%3B_Sir_Thomas_Browne_by_Joan_Carlile.jpg)

Browne's first literary work was Religio Medici (The Religion of a Physician). This work was circulated as a manuscript among his friends. It surprised him when an unauthorised edition appeared in 1642, since the work included several unorthodox religious speculations. An authorised text appeared in 1643, with some of the more controversial views removed. The expurgation did not end the controversy: in 1645, Alexander Ross attacked Religio Medici in his Medicus Medicatus (The Doctor, Doctored) and, in common with much Protestant literature, the book was placed upon the Papal Index Librorum Prohibitorum in the same year. [5]

In 1646, Browne published his encyclopaedia, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or, Enquiries into Very many Received Tenets, and commonly Presumed Truths, whose title refers to the prevalence of false beliefs and "vulgar errors". A sceptical work that debunks a number of legends circulating at the time in a methodical and witty manner, it displays the Baconian side of Browne—the side that was unafraid of what at the time was still called "the new learning". The book is significant in the history of science because it promoted an awareness of up-to-date scientific journalism.

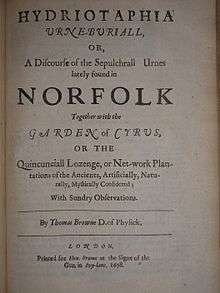

Browne's last publication during his lifetime were two philosophical Discourses which are closely related to each other in concept. The first, Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial, or a Brief Discourse of the Sepulchral Urns lately found in Norfolk (1658) inspired by the discovery of some Bronze Age burials in earthenware vessels found in Norfolk, resulted in a literary meditation upon death, the funerary customs of the world and the ephemerality of fame. The other discourse in the diptych is antithetical in style, subject-matter and imagery. The Garden of Cyrus, or The Quincuncial Lozenge, or Network Plantations of the Ancients, Artificially, Naturally, and Mystically Considered (1658) features the quincunx which is used by Browne to demonstrate evidence of the Platonic forms in art and nature. [6]

Later life and knighthood

In Religio Medici, Browne confirmed his belief, in accordance with the vast majority of seventeenth century European society, in the existence of angels and witchcraft. He attended the 1662 Bury St. Edmunds witch trial, where his citation of a similar trial in Denmark may have influenced the jury's minds of the guilt of two accused women, who were subsequently executed for the crime of witchcraft.

In 1671 King Charles II, accompanied by the Court, visited Norwich. The courtier John Evelyn, who had occasionally corresponded with Browne, took good use of the royal visit to call upon "the learned doctor" of European fame and wrote of his visit, "His whole house and garden is a paradise and Cabinet of rarities and that of the best collection, amongst Medails, books, Plants, natural things".[7]

During his visit, Charles visited Browne's home. A banquet was held in the Civic Hall St. Andrews for the Royal visit. Obliged to honour a notable local, the name of the Mayor of Norwich was proposed to the King for knighthood. The Mayor, however, declined the honour and proposed Browne's name instead.[8]

Death and aftermath

Sir Thomas Browne died on his 77th birthday, 19 October 1682. His Library was held in the care of his eldest son Edward until 1708. The auction of Browne and his son Edward's libraries in January 1711 was attended by Hans Sloane. Editions from Sir Thomas Browne's Library subsequently became included in the founding collection of the British Library.[9]

His skull became the subject of local dispute when it was removed from his lead coffin when accidentally re-opened by workmen in 1840. It was not re-interred until 4 July 1922 when it was registered in the church of Saint Peter Mancroft as aged 317 years.[10] Browne's coffin-plate, which was stolen the same time as his skull, was also eventually recovered, broken into two halves, one of which is on display at St. Peter Mancroft. Alluding to the commonplace opus of alchemy it reads, Amplissimus Vir Dns. Thomas Browne, Miles, Medicinae Dr., Annos Natus 77 Denatus 19 Die mensis Octobris, Anno. Dni. 1682, hoc Loculo indormiens. Corporis Spagyrici pulvere plumbum in aurum Convertit. — translated from Latin as The esteemed Gentleman Thomas Browne, Knight, Doctor of Medicine, 77 years old, died on the 19th of October in the year of Our Lord 1682 and lies sleeping in this coffin. With the dust of the alchemical body he converts lead into gold. The origin of the invented word spagyrici are from the Greek of: Spao to tear open, + ageiro to collect, a signature neologism coined by Paracelsus to define his medicine-oriented alchemy; the origins of iatrochemistry, being first advanced by him. Browne's coffin-plate verse, along with the collected works of Paracelsus and several followers of the Swiss physician listed in his library, are evidence that although sometimes highly critical of Paracelsus, nevertheless, like the 'Luther of Medicine', he believed in palingenesis, physiognomy, alchemy, astrology and the kabbalah.[11]

Autobiography

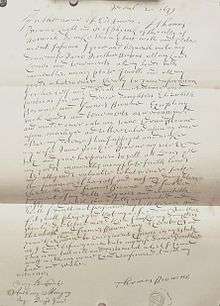

On 14 March 1673, Browne sent a short autobiography to the antiquarian John Aubrey, presumably for Aubrey's collection of Brief Lives, which provides an introduction to his life and writings.

- ...I was born in St Michael's Cheap in London, went to school at Winchester College, then went to Oxford, spent some years in foreign parts, was admitted to be a Socius Honorarius of the College of Physicians in London, Knighted September 1671, when the King Charles II, the Queen and Court came to Norwich. Writ Religio Medici in English, which was since translated into Latin, French, Italian, High and Low Dutch, Pseudodoxia Epidemica, or Enquiries into Common and Vulgar Errors translated into Dutch four or five years ago. Hydriotaphia, or Urn Buriall. Hortus Cyri, or de Quincunce. Have some miscellaneous tracts which may be published...(Letters 376)[12]

Literary works

- Religio Medici (1643)

- Pseudodoxia Epidemica (1646–72)

- Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial (1658)

- The Garden of Cyrus (1658)

- A Letter to a Friend (1656; pub. 1690)

- Christian Morals (1670s; pub. 1716)

- Musaeum Clausum Tract 13 from Miscellaneous Tracts first pub. 1684

- See also Library of Sir Thomas Browne

Literary influence

Browne is widely considered one of the most original writers in the English language. The freshness and ingenuity of his mind invested everything he touched with interest; while on more important subjects his style, if frequently ornate and Latinate, often rises to the highest pitch of stately eloquence. His paradoxical place in the history of ideas, as equally, a devout Christian, a promoter of the new inductive science and adherent of ancient esoteric learning, have greatly contributed to his ambiguity in the history of ideas. For these reasons, one literary critic succinctly assessed him as "an instance of scientific reason lit up by mysticism in the Church of England".[13] However, the complexity of Browne's labyrinthine thought processes, his highly stylized language, along with his many allusions to Biblical, Classical and contemporary learning, along with esoteric authors, are each contributing factors for why he remains obscure, little-read and thus, misunderstood.[14]

Browne appears at No. 69 in the Oxford English Dictionary's list of top cited sources. He has 775 entries in the OED of first usage of a word, is quoted in a total of 4131 entries of first evidence of a word, and is quoted 1596 times as first evidence of a particular meaning of a word. Examples of his coinages, many of which are of a scientific or medical nature, include 'ambidextrous','antediluvian', 'analogous', 'approximate', 'ascetic', 'anomalous', 'carnivorous', 'coexistence', 'coma', 'compensate', 'computer', 'cryptography', 'cylindrical', 'disruption','ergotisms', 'electricity', 'exhaustion', 'ferocious', 'follicle', 'generator', 'gymnastic', 'hallucination', 'herbaceous', 'holocaust', 'insecurity', 'indigenous', 'jocularity', 'literary', 'locomotion', 'medical', 'migrant', 'mucous', 'prairie', 'prostate', 'polarity', 'precocious', 'pubescent', 'therapeutic', 'suicide', 'ulterior', 'ultimate' and 'veterinarian'.[15][16]

The influence of his literary style spans four centuries.

- In the 18th century, Samuel Johnson, who shared Browne's love of the Latinate, wrote a brief Life in which he praised Browne as a faithful Christian and assessed his prose thus:

"His style is, indeed, a tissue of many languages; a mixture of heterogeneous words, brought together from distant regions, with terms originally appropriated to one art, and drawn by violence into the service of another. He must, however, be confessed to have augmented our philosophical diction; and, in defence of his uncommon words and expressions, we must consider, that he had uncommon sentiments, and was not content to express, in many words, that idea for which any language could supply a single term".[17]

- In the 19th century Browne's reputation was revived by the Romantics. Thomas De Quincey, Samuel Taylor Coleridge, and Charles Lamb (who considered himself the rediscoverer of Browne) were all admirers. Carlyle was also influenced by him.[18]

- The American novelist Herman Melville, heavily influenced by his style, deemed him a "crack'd Archangel." [19]

- The epigraph of Edgar Allan Poe's "The Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1841) is from Browne's Hydriotaphia,(Chap.5): "What song the Syrens sang, or what name Achilles assumed when he hid himself among women, although puzzling questions, are not beyond all conjecture".

- The novelist Joseph Conrad prefaced his 1913 novel Chance with a quotation by Browne.

- The English author Virginia Woolf wrote two short essays about him, observing in 1923, "Few people love the writings of Sir Thomas Browne, but those that do are the salt of the earth." [20]

In the 20th century those who have admired Browne include:

- The American natural historian and palaeontologist Stephen Jay Gould.[21]

- The theosophist Madame Blavatsky.[22]

- The Scottish psychologist R. D. Laing, who opens his work The Politics of Experience with a quotation by him : " thus is man that great and true Amphibian whose nature is disposed to live not only like other creatures in divers elements, but in divided and distinguished worlds."[23]

- The composer William Alwyn wrote a symphony in 1973 based upon the rhythmical cadences of Browne's literary work Hydriotaphia, Urn Burial.[24]

- The American author Armistead Maupin includes a quote from Religio Medici in the preface to the third in his Tales of the City novels, Further Tales of the City, first published in 1982.

- The Canadian physician William Osler (1849–1919), the "founding father of modern medicine", was a well-read admirer of Browne.[25][26][27]

- The German author W.G. Sebald wrote of Browne in his semi-autobiographical novel The Rings of Saturn (1995).[28]

- The Argentinian writer Jorge Luis Borges alluded to Browne throughout his literary writings, from his first publication, Fervor de Buenos Aires (1923) until his last years. He described Browne as "the best prose writer in the English language". Such was his admiration of Browne as a literary stylist and thinker that late in his life (Interview 25 April 1980) he stated of himself, alluding to his self-portrait in "Tlön, Uqbar, Orbis Tertius" (1940):[29]

I am merely a word for Chesterton, for Kafka, and Sir Thomas Browne — I love him. I translated him into 17th century Spanish and it worked very well. We took a chapter out of Urne Buriall and we did that into Quevedo's Spanish and it went very well.[29]

- In his short story "The Celestial Omnibus", published in 1911, E. M. Forster makes Browne the first "driver" that the young protagonist encounters on the magical omnibus line that transports its passengers to a place of direct experience of the aesthetic sublime reserved for those who internalise the experience of poetry, as opposed to those who merely acquire familiarity with literary works for snobbish prestige.[30] The story is an allegory about true appreciation of poetry and literature versus pedantry.

- In North Towards Home, Willie Morris quotes Sir Thomas Browne's Urn Burial from memory as he walks up Park Avenue with William Styron: "'And since death must be the Lucina of life, and even Pagans could doubt, whether thus to live were to die; since our longest sun sets at right descensions, and makes but winter arches, and therefore it cannot be long before we lie down in darkness and have our light in ashes...' At that instant I was almost clipped by a taxicab, and the driver stuck his head out and yelled, 'Aincha got eyes in that head, ya bum?'"[31]

- William Styron prefaced his 1951 novel Lie Down in Darkness with the same quotation as noted above in the remarks about Willie Morris's memoir. The title of Styron's novel itself comes from that quotation.

- Spanish writer Javier Marías translated two works of Browne into Spanish, Religio Medici and Hydriotaphia.[32]

- The British ornithologist Tim Birkhead has said of Browne:

One of my favourite early ornithologists is best known among birders for his account of the birds of Norfolk in the mid 1600s. For me it is also as a demolisher of fake news that I love Sir Thomas Browne. Living in the mid 1600s at the start of the scientific revolution Browne sought to disprove some of the nonsense and folklore about birds — vulgar errors, as he called them.

Portraits and influence in the visual arts

The National Portrait Gallery in London has a fine contemporary portrait by Joan Carlile of Sir Thomas Browne and his wife Dorothy, Lady Browne (née Mileham).

More recent sculptural portraits include Henry Alfred Pegram's statue of Sir Thomas contemplating with urn in Norwich. This statue occupies the central position in the Haymarket beside St. Peter Mancroft, not far from the site of his house. It was erected in 1905 and moved from its original position in 1973.

In 1931 the English painter Paul Nash was invited to illustrate a book of his own choice, Nash choose Sir Thomas Browne's Urn Burial and The Garden of Cyrus, providing the publisher with a set of 32 illustrations to accompany Browne's Discourses. The edition was published in 1932. A pencil drawing by Nash called "Urne Buriall: Teeth, Bones and Hair" is held by Birmingham Museums Trust.

In 2005 a small standing figure in silver and bronze, commissioned for the 400th anniversary of Browne's birth, was sculpted by Robert Mileham.

In 2016 the North Sea Magical Realists, the artists Peter Rodulfo and Mark Burrell elected Browne as an honorary 'Great-Grandfather' of the movement, both painting an item from Browne's Musaeum Clausum (from Rarities in Pictures section numbers 3 and 12).

References

- ↑ Eccles, J. C.; Gibson, W. C. (1979). Sherrington: His Life and Thought. Springer Science+Business Media.

His library was housed mainly in one large room with open shelves reaching to the ceiling and a couple of turntable bookcases, one of them completely filled with editions of his favourite among all books, Sir Thomas Browne's Religio Medici

- ↑ R. H. Robbins, "Browne, Sir Thomas (1605–1682)", Oxford Dictionary of National Biography, Oxford University Press, 2004; online edn, May 2008 accessed 16 Feb 2013

- ↑ "Munks Roll Details for Thomas (Sir) Browne". munksroll.rcplondon.ac.uk. Retrieved 2018-05-30.

- ↑ Breathnach, Caoimhghín S (January 2005). "Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682)". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 98 (1): 33–36. doi:10.1258/jrsm.98.1.33. PMC 1079241. PMID 15632239.

- ↑ J.S. Finch A doctor's Life of Faith and Science. Princeton 1950

- ↑ Frank Huntley, Sir Thomas Browne : A biographical and Critical Study Ann Arbor University of Michigan Press, 1962

- ↑ The Diary of John Evelyn ed. John Eve pub. Everyman (2003)

- ↑ Simon Wilkins Supplementary Memoir citing Francis Blomefield Sir Thomas Browne Collected Works Vol. I pub. 1836

- ↑ A Facsimile of the 1711 Sales Auction Catalogue of Sir Thomas Browne and his son Edward's Libraries. Introduction, notes and index by J.S. Finch (E.J. Brill: Leiden, 1986) Page 7

- ↑ Colin Dickey. The Fate of His Bones // Cabinet Magazine. Issue 28: Bones. Winter 2007/08.

- ↑ Manchester Guardian 19 October 1905

- ↑ Preston, Claire (1995). Sir Thomas Browne: Selected Writings. Manchester: Carcanet. pp. i. ISBN 1-85754-690-3.

- ↑ Sencourt R., Outflying Philosophy: A Literary Study of the Religious Element in the Poems and Letters of John Donne and in the Works of Sir Thomas Browne., Ardent Media, 1925, p. 126

- ↑ http://www.levity.com/alchemy/sir_thomas_browne.html

- ↑ Sir Thomas Browne and the Oxford English Dictionary, Denny Hilton, OED, accessed February 2013.

- ↑ Adam Nicolson, The Century That Wrote Itself, BBC Four, 21 April 2013

- ↑ Johnson S., "Life of Browne" in Thomas Browne's Christian Morals, London, 1765

- ↑ Reid Barbour, Thomas Browne A Life OUP 2013

- ↑ (quoted in the Historical Note, Elizabeth S. Foster, page 661: "He has borrowed Sir Thomas Brown[e] of me," Evert A. Duyckinck wrote his brother on 18 March 1848, "and says finely of the speculations of the Religio Medici that Browne is a kind of 'crack'd Archangel!' Was ever anything of this sort said before by a sailor?" in "Mardi and A Voyage Thither," Northwestern University Press, c. 1970, paper bound edition)

- ↑ review by Woolf of the Golden Cockerel edition of the Works of Sir Thomas Browne, published in Times Literary Supplement (1923)

- ↑ "Age-Old Fallacies of Thinking and Stinking", in "I Have Landed: Splashes and Reflections in Natural History"

- ↑ Isis Unveiled 1877 vol. 1 H.P. Blavatsky p. 36

- ↑ from Religio medici, cf. Laing R., (1967), The Politics of Experience and The Bird of Paradise, Harmondsworth: Penguin Books, p. 15

- ↑ Naxos B000A17GGK Royal Liverpool Philharmonic Orchestra David Lloyd-Jones 2005

- ↑ Segall, N (1985). "William Osler and Thomas Browne, a friendship of fifty-two years; Sir Thomas pervades Sir William's library". Korot. 8 (11–12): 150–165. PMID 11614038.

- ↑ Martens, P (1992). "The faiths of two doctors: Thomas Browne and William Osler". Perspect. Biol. Med. 36 (1): 120–128. PMID 1475152.

- ↑ Hookman, P (1995). "A comparison of the writings of Sir William Osler and his exemplar, Sir Thomas Browne". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 72 (1): 136–150. PMC 2359421. PMID 7581308.

- ↑ Archived 11 May 2008 at the Wayback Machine.

- 1 2 "Interview by Daniel Bourne in Artful Dodge". 25 April 1980.

- ↑ Forster, E.M., Selected Stories, Penguin Classics, 2001, pp.30-46, ISBN 978-0141186191

- ↑ Willie Morris, North Towards Home, New York: Vintage; part 3 (page 313 ff); ISBN 0375724605 ISBN 978-0375724602; The quote is from Chapter 5.

- ↑ La religión de un médico. El enterramiento en urnas (Hydriotaphia). De los sueños, nota previa, traducción y epílogo de Javier Marías, Barcelona: Reino de Redonda, primera edición de septiembre de 2002 ISBN 978-84-931471-4-3.

- ↑ https://markavery.info/2018/08/30/guest-blog-fake-eggs-fake-news-and-guillemots-by-tim-birkhead/

Sources

- Reid Barbour and Claire Preston (eds), Sir Thomas Browne: The World Proposed (Oxford, OUP, 2008).

- Breathnach, Caoimhghín S (January 2005). "Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682)". Journal of the Royal Society of Medicine. 98 (1): 33–6. doi:10.1258/jrsm.98.1.33. PMC 1079241. PMID 15632239.

- Mellick, Sam (June 2003). "Sir Thomas Browne: physician 1605–1682 and the Religio Medici". ANZ. 73 (6): 431–7. doi:10.1046/j.1445-2197.2003.t01-1-02646.x. PMID 12801344.

- Hughes, J T (May 2001). "The medical education of Sir Thomas Browne, a seventeenth-century student at Montpellier, Padua, and Leiden". Journal of Medical Biography. 9 (2): 70–6. PMID 11304631.

- Böttiger, L E (January 1995). "[From Thomas Browne to Dannie Abse. English physicians-writers over four centuries]". Lakartidningen. 92 (3): 176–80. PMID 7837855.

- Hookman, P (1995). "A comparison of the writings of Sir William Osler and his exemplar, Sir Thomas Browne". Bulletin of the New York Academy of Medicine. 72 (1): 136–50. PMC 2359421. PMID 7581308.

- Dunn, P M (January 1994). "Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682) and life before birth". Arch. Dis. Child. Fetal Neonatal Ed. 70 (1): F75–6. doi:10.1136/fn.70.1.F75. PMC 1060996. PMID 8117135.

- Martens, P (1992). "The faiths of two doctors: Thomas Browne and William Osler". Perspect. Biol. Med. 36 (1): 120–8. PMID 1475152.

- White, H (1988). "An introduction to Thomas Browne (1605–1682) and his connections with Winchester College". Journal of Medical Biography. 6 (2): 120–2. PMID 11620012.

- Segall, H N (1985). "William Osler and Thomas Browne, a friendship of fifty-two years; Sir Thomas pervades Sir William's library". Korot. 8 (11–12): 150–65. PMID 11614038.

- Webster, A (1982). "Threefold cord of religion, science, and literature in the character of Sir Thomas Browne". BMJ. 285 (6357): 1801–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6357.1801. PMC 1500275. PMID 6816374.

- Dirckx, J H (October 1982). "Sir Thomas Browne (1605–1682). A model for medical humanists". JAMA. 248 (15): 1845–7. doi:10.1001/jama.248.15.1845. PMID 6750160.

- Huntley, F L (July 1982). ""Well Sir Thomas?": oration to commemorate the tercentenary of the death of Sir Thomas Browne". BMJ. 285 (6334): 43–7. doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6334.43. PMC 1499109. PMID 6805807.

- Shaw, A B (July 1982). "Sir Thomas Browne: the man and the physician". BMJ. 285 (6334): 40–2. doi:10.1136/bmj.285.6334.40. PMC 1499136. PMID 6805806.

- Schoeck, R J (1982). "Sir Thomas Browne and the Republic of Letters: Introduction". English language notes. 19 (4): 299–312. PMID 11616938.

- Geis, G; Bunn I (1981). "Sir Thomas Browne and witchcraft: a cautionary tale for contemporary law and psychiatry". International Journal of Law and Psychiatry. 4 (1–2): 1–11. doi:10.1016/0160-2527(81)90017-0. PMID 7035381.

- Shaw, A B (July 1978). "Vicary Lecture, 1977. Sir Thomas Browne: the man and the physician". Annals of the Royal College of Surgeons of England. 60 (4): 336–44. PMC 2492123. PMID 352233.

- Martin, D C (May 1976). "Sir Thomas Browne 1605–1682". Investigative urology. 13 (6): 449. PMID 773893.

- Buxton, R W (December 1970). "Sir Thomas Browne and the Religio Medici". Surgery, gynaecology & obstetrics. 131 (6): 1164–70. PMID 4920856.

- Huston, K G (July 1970). "Sir Thomas Browne, Thomas le Gros, and the first edition of Pseudodoxia Epidemica, 1646". Journal of the history of medicine and allied sciences. 25 (3): 347–8. doi:10.1093/jhmas/XXV.3.347. PMID 4912887.

- Merton, S (1966). "Old and new physiology in Sir Thomas Browne: digestion and some other functions". Isis, an international review devoted to the history of science and its cultural influences. 57 (2): 249–59. doi:10.1086/350117. PMID 5335398.

- Keynes, G (December 1965). "Sir Thomas Browne". BMJ. 2 (5477): 1505–10. doi:10.1136/bmj.2.5477.1505. PMC 1847298. PMID 5321828.

- Doyle, B R (October 1963). "Sir Thomas Browne, Physician And Humanist". McGill medical journal. 32: 79–83. PMID 14074523.

- Schenk, J M (April 1961). "PSYCHIATRIC ASPECTS OF SIR THOMAS BROWNE WITH A NEW EVALUATION OF HIS WORK". Medical history. 5 (2): 157–66. doi:10.1017/s0025727300026120. PMC 1034604. PMID 13748180.

- Finch, J S (August 1956). "The lasting influence of Sir Thomas Browne". Transactions & studies of the College of Physicians of Philadelphia. 24 (2): 59–69. PMID 13360999.

- MacKinnon, M (1953). "An unpublished consultation letter of Sir Thomas Browne". Bulletin of the history of medicine. 27 (6): 503–11. PMID 13115796.

- Viets, H R (September 1953). "A fragment from Sir Thomas Browne". N. Engl. J. Med. 249 (11): 455. doi:10.1056/NEJM195309102491107. PMID 13087622.

External links

| Wikisource has original works written by or about: Thomas Browne |

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: Thomas Browne |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to Thomas Browne. |

- The Sir Thomas Browne Page at the University of Chicago, a comprehensive site with the complete works mentioned above, plus the minor works; Samuel Johnson's Life of Browne, Kenelm Digby's Observations on Religio Medici, and Alexander Ross's Medicus Medicatus; and background material, such as many of Browne's sources.

- Quotations by Sir Thomas Browne at Quotidiana.org.

- The Thomas Browne Seminar

- Thomas Browne Bibliography

- Aquarium of Vulcan

- Alchemical and Hermetic thought in the literary works of Sir Thomas Browne

- Spiritual and literary affinity between Julian of Norwich and Sir Thomas Browne.

- Prayer and Prophecy in Browne's life and writings.

- Interview with Jorge Luis Borges, 25 April 1980, discussing Browne

- Works by Thomas Browne at Project Gutenberg

- Works by or about Thomas Browne at Internet Archive

- Works by Thomas Browne at LibriVox (public domain audiobooks)

- Sir Thomas Browne Quotes at Convergence