R. D. Laing

| Ronald David Laing | |

|---|---|

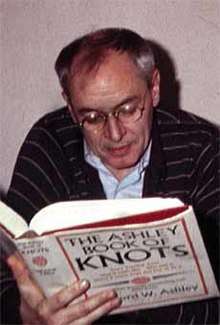

Laing in 1983, perusing The Ashley Book of Knots (1944) | |

| Born |

7 October 1927 Govanhill, Glasgow, Scotland |

| Died |

23 August 1989 (aged 61) Saint-Tropez, France |

| Known for | Medical model |

| Scientific career | |

| Fields | Psychiatry |

| Influences |

Eugène Minkowski Jean-Paul Sartre |

| Influenced |

David Abram Loren Mosher[1] |

Ronald David Laing (7 October 1927 – 23 August 1989), usually cited as R. D. Laing, was a Scottish psychiatrist who wrote extensively on mental illness – in particular, the experience of psychosis. Laing's views on the causes and treatment of psychopathological phenomena were influenced by his study of existential philosophy and ran counter to the chemical and electroshock methods that had become psychiatric orthodoxy. Taking the expressed feelings of the individual patient or client as valid descriptions of lived experience rather than simply as symptoms of mental illness, Laing regarded schizophrenia as a theory not a fact. Though associated in the public mind with anti-psychiatry he rejected the label.[2] Politically, he was regarded as a thinker of the New Left.[3] Laing was portrayed in the 2017 film Mad to Be Normal.

Early years

Laing was born in the Govanhill district of Glasgow on 7 October 1927, the only child of civil engineer David Park MacNair Laing and Amelia Glen Laing (née Kirkwood).[4]:7 Laing described his parents – his mother especially – as being somewhat anti-social, and demanding the maximum achievement from him. Although his biographer son largely discounted Laing's account of his childhood, an obituary by an acquaintance of Laing asserted that about his parents – "the full truth he told only to a few close friends".[5][6]

He was educated initially at Sir John Neilson Cuthbertson Public School and after four years transferred to Hutchesons' Grammar School. Described variously as clever, competitive or precocious, he studied Classics, particularly philosophy, including through reading books from the local library. Small and slightly built, Laing participated in distance running; he was also a musician, being made an Associate of the Royal College of Music. He studied medicine at the University of Glasgow. During his medical degree he set up a "Socratic Club", of which the philosopher Bertrand Russell agreed to be President. Laing failed his final exams. In a partial autobiography, Wisdom, Madness and Folly, Laing said he felt remarks he made under the influence of alcohol at a university function had offended the staff and led to him being failed on every subject including some he was sure he had passed. After spending six months working on a psychiatric unit, Laing passed the re-sits in 1951 to qualify as a medical doctor.[7]

Career

Laing spent a couple of years as a psychiatrist in the British Army Psychiatric Unit at Netley, where as he later recalled, those trying to fake schizophrenia to get a lifelong disability pension were likely to get more than they had bargained for as Insulin shock therapy was being used.[8] In 1953 Laing returned to Glasgow, participated in an existentialism-oriented discussion group, and worked at the Glasgow Royal Mental Hospital[9] The hospital was influenced by David Henderson's school of thought, which may have exerted an unacknowledged influence on Laing; he became the youngest consultant in the country.[10] .[7] Laing's colleagues characterised him as "conservative" for his opposition to Electroconvulsive therapy and the new drugs that were being introduced.[11]

In 1956 Laing went to train on a grant at the Tavistock Institute in London, widely known as a centre for the study and practice of psychotherapy (particularly psychoanalysis). At this time, he was associated with John Bowlby, D. W. Winnicott and Charles Rycroft. He remained at the Tavistock Institute until 1964.[12]

In 1965 Laing and a group of colleagues created the Philadelphia Association and started a psychiatric community project at Kingsley Hall, where patients and therapists lived together.[13] The Norwegian author Axel Jensen contacted Laing at Kingsley Hall after reading his book The Divided Self, which had been given to him by Noel Cobb. Jensen was treated by Laing and subsequently they became close friends. Laing often visited Jensen onboard his ship Shanti Devi, which was his home in Stockholm.[14]

In October 1972, Laing met Arthur Janov, author of the popular book The Primal Scream. Though Laing found Janov modest and unassuming, he thought of him as a 'jig man' (someone who knows a lot about a little). Laing sympathized with Janov, but regarded his primal therapy as a lucrative business, one which required no more than obtaining a suitable space and letting people 'hang it all out.'[15]

Inspired by the work of American psychotherapist Elizabeth Fehr, Laing began to develop a team offering "rebirthing workshops" in which one designated person chooses to re-experience the struggle of trying to break out of the birth canal represented by the remaining members of the group who surround him or her.[16] Many former colleagues regarded him as a brilliant mind gone wrong but there were some who thought Laing was somewhat psychotic.[4]

Laing and anti-psychiatry

Laing was seen as an important figure in the anti-psychiatry movement, along with David Cooper, although he never denied the value of treating mental distress.

R.D. Laing, The Politics of Experience, p. 107

He also challenged psychiatric diagnosis itself, arguing that diagnosis of a mental disorder contradicted accepted medical procedure: diagnosis was made on the basis of behaviour or conduct, and examination and ancillary tests that traditionally precede the diagnosis of viable pathologies (like broken bones or pneumonia) occurred after the diagnosis of mental disorder (if at all). Hence, according to Laing, psychiatry was founded on a false epistemology: illness diagnosed by conduct, but treated biologically.

Laing maintained that schizophrenia was "a theory not a fact"; he believed the models of genetically inherited schizophrenia being promoted by biologically based psychiatry were not accepted by leading medical geneticists.[17] He rejected the "medical model of mental illness"; according to Laing diagnosis of mental illness did not follow a traditional medical model; and this led him to question the use of medication such as antipsychotics by psychiatry. His attitude to recreational drugs was quite different; privately, he advocated an anarchy of experience.[18]

Personal life

In his early life, Laing's father, David, an electrical engineer who had served in the Royal Air Force, seems often to have come to blows with his own brother, and himself had a breakdown for three months when Laing was a teenager. His mother Amelia, according to some speculation and rumour about her behaviour, has been described as "psychologically peculiar".[4]

Laing was troubled by his own personal problems, suffering from both episodic alcoholism and clinical depression, according to his self-diagnosis in a BBC Radio interview with Anthony Clare in 1983,[19] although he reportedly was free of both in the years before his death. These admissions were to have serious consequences for Laing as they formed part of the case against him by the General Medical Council which led to him ceasing to practise medicine. He died at age 61 of a heart attack while playing tennis with his colleague and friend Robert W. Firestone.[20]

Laing fathered six sons and four daughters by four women. His son Adrian, speaking in 2008, said, "It was ironic that my father became well known as a family psychiatrist, when, in the meantime, he had nothing to do with his own family."[21] His daughter Fiona was born 7 December 1952.[22] His daughter Susan born September 1954 died in March 1976, aged 21, of leukemia.[23] Adam, his oldest son by his second marriage, was found dead in May 2008, in a tent on a Mediterranean island. He had died of a heart attack, aged 41.[24]

Works

In 1913, psychiatrist and philosopher Karl Jaspers had pronounced, in his work, General Psychopathology, that many of the symptoms of mental illness (and particularly of delusions) were "un-understandable", and therefore were worthy of little consideration except as a sign of some other underlying primary disorder. Then, in 1956, Gregory Bateson and his colleagues, Donald Jackson, and Jay Haley articulated a theory of schizophrenia as stemming from double bind situations where a person receives different or contradictory messages.[25] The perceived symptoms of schizophrenia were therefore an expression of this distress, and should be valued as a cathartic and trans-formative experience. Laing argued a similar account for psychoses: that the strange behavior and seemingly confused speech of people undergoing a psychotic episode were ultimately understandable as an attempt to communicate worries and concerns, often in situations where this was not possible or not permitted. Laing stressed the role of society, and particularly the family, in the development of "madness" (his term).

Laing saw psychopathology as being seated not in biological or psychic organs – whereby environment is relegated to playing at most only an accidental role as immediate trigger of disease (the "stress diathesis model" of the nature and causes of psychopathology) – but rather in the social cradle, the urban home, which cultivates it, the very crucible in which selves are forged. This re-evaluation of the locus of the disease process – and consequent shift in forms of treatment – was in stark contrast to psychiatric orthodoxy (in the broadest sense we have of ourselves as psychological subjects and pathological selves). Laing was revolutionary in valuing the content of psychotic behaviour and speech as a valid expression of distress, albeit wrapped in an enigmatic language of personal symbolism which is meaningful only from within their situation.

Laing expanded the view of the "double bind" hypothesis put forth by Bateson and his team, and came up with a new concept to describe the highly complex situation that unfolds in the process of "going mad" – an "incompatible knot".

Laing never denied the existence of mental illness, but viewed it in a radically different light from his contemporaries. For Laing, mental illness could be a transformative episode whereby the process of undergoing mental distress was compared to a shamanic journey. The traveler could return from the journey with (supposedly) important insights, and may have become (in the views of Laing and his followers) a wiser and more grounded person as a result.

In The Divided Self (1960), Laing contrasted the experience of the "ontologically secure" person with that of a person who "cannot take the realness, aliveness, autonomy and identity of himself and others for granted" and who consequently contrives strategies to avoid "losing his self".[26] In Self and Others (1961), Laing's definition of normality shifted somewhat.[27]

Laing also wrote poetry and his poetry publications include Knots (1970, published by Penguin) and Sonnets (1979, published by Michael Joseph).

Laing appears, alongside his son Adam, on the 1980 album Miniatures - a sequence of fifty-one tiny masterpieces edited by Morgan Fisher, performing the song "Tipperary".[28]

Influence

In 1965 Laing co-founded the UK charity the Philadelphia Association, concerned with the understanding and relief of mental suffering, which he also chaired.[29] His work influenced the wider movement of therapeutic communities, operating in less "confrontational" (in a Laingian perspective) psychiatric settings. Other organizations created in a Laingian tradition are the Arbours Association[30], the New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling in London[31], and the R.D. Laing in the 21st Century Symposium[32] held annually at Esalen Institute, where Laing frequently taught.

Films and plays about Laing

- Ah, Sunflower (1967). Short film by Robert Klinkert and Iain Sinclair, filmed around the Dialectics of Liberation conference and featuring Laing, Allen Ginsberg, Stokely Carmichael and others.

- Cain's Film (1969). Short film by Jamie Wadhawan on Alexander Trocchi, featuring other counter-cultural figures in London at the time including Laing, William Burroughs and Davy Graham.

- Family Life (1971). Reworking of The Wednesday Play: In Two Minds (1967) that "explored the issue of schizophrenia and the ideas of the radical psychiatrist R. D. Laing".[33] Both were directed by Ken Loach from scripts by David Mercer.

- Asylum (1972). Documentary directed by Peter Robinson showing Laing's psychiatric community project where patients and therapists lived together. Laing also appears in the film.

- Knots (1975). Film adapted from Laing's 1970 book and Edward Petherbridge's play.

- How Does It Feel? (1976). Documentary on physical senses and creativity featuring Laing, Joseph Beuys, David Hockney, Elkie Brooks, Michael Tippett and Richard Gregory.

- Birth with R.D. Laing (1978). Documentary on the "institutionalization of childbirth practices in Western society".[34]

- R.D. Laing's Glasgow (1979). An episode of the Canadian TV series Cities.

- Did You Used to be R.D. Laing? (1989). Documentary portrait of Laing by Kirk Tougas and Tom Shandel. Adapted for the stage in 2000 by Mike Maran.

- Eros, Love & Lies (1990). Documentary on Laing.

- What You See Is Where You're At (2001). A collage of found footage by Luke Fowler on Laing's experiment in alternative therapy at Kingsley Hall.

- The Trap 1 (TV series) (2007) - F**k you Buddy! - Adam Curtis. Covering Laings' modeling of familial interactions using game theory.

- All Divided Selves (2011). Another collage of archive material and new footage by Luke Fowler.

- Mad to Be Normal (2017). A biopic starring David Tennant as Laing and directed by Robert Mullan.[35]

Selected bibliography

- Laing, R.D. (1960) The Divided Self: An Existential Study in Sanity and Madness. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Laing, R.D. (1961) The Self and Others. London: Tavistock Publications.[36]

- Laing, R.D. and Esterson, A. (1964) Sanity, Madness and the Family. London: Penguin Books.

- Laing, R.D. and Cooper, D.G. (1964) Reason and Violence: A Decade of Sartre's Philosophy. (2nd ed.) London: Tavistock Publications Ltd.

- Laing, R.D., Phillipson, H. and Lee, A.R. (1966) Interpersonal Perception: A Theory and a Method of Research. London: Tavistock Publications.

- Laing, R.D. (1967) The Politics of Experience and the Bird of Paradise. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Laing, R.D. (1970) Knots. London: Penguin. excerpt, movie (IMDB)

- Laing, R.D. (1971) The Politics of the Family and Other Essays. London: Tavistock Publications.

- Laing, R.D. (1972) Knots. New York: Vintage Press.

- Laing, R.D. (1976) Do You Love Me? An Entertainment in Conversation and Verse. New York: Pantheon Books.

- Laing, R.D. (1976) Sonnets. London: Michael Joseph.

- Laing, R.D. (1976) The Facts of Life. London: Penguin.

- Laing, R.D. (1977) Conversations with Adam and Natasha. New York: Pantheon.

- Laing, R.D. (1982) The Voice of Experience: Experience, Science and Psychiatry. Harmondsworth: Penguin.

- Laing, R.D. (1985) Wisdom, Madness and Folly: The Making of a Psychiatrist 1927-1957. London: Macmillan.

- Mullan, B. (1995) Mad to be Normal: Conversations with R.D. Laing. London: Free Association Books.

- Russell, R. and R.D. Laing (1992) R.D. Laing and Me: Lessons in Love. New York: Hillgarth Press. (download free on www.rdlaing.org

- Mott, F.J. and R.D. Laing (2014) Mythology of the Prenatal Life London: Starwalker Press. (Hand-written annotations [c.1977] by R.D. Laing are included in the text, revealing Laing's own thoughts and associative material on prenatal psychology as he studied this book.[37] )

See also

- Joseph Berke - psychoanalyst and therapist to Mary Barnes

- Existential therapy

- Family nexus

- Kraepelin's enigmatic dream speech - analogous to psychotic speech

- Alice Miller

- Eugène Minkowski - a psychiatrist commended by Laing

- Martti Olavi Siirala

- David Smail - a more modern writer with similarly unconventional views

- Stephen Ticktin

- The Trap - a three-part BBC series which, in its first episode, concentrates on Laing's work

- Emmy van Deurzen

References

- ↑ "SLS - Colloquia - Still Crazy After All These Years". laingsociety.org. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ Kotowicz, Zbigniew (1997), R.D. Laing and the paths of anti-psychiatry, Routledge

- ↑ "R. D. Laing," in The New Left, edited by Maurice Cranston, The Library Press, 1971, pp. 179-208. "Ronald Laing must be accounted one of the main contributors to the theoretical and rhetorical armoury of the contemporary Left."

- 1 2 3 Miller, Gavin (2004). R.D. Laing. Edinburgh review, introductions to Scottish culture. Edinburgh: Edinburgh Review in association with Edinburgh University Press. ISBN 1859332706. OCLC 58554944.

- ↑ R. D. Laing: a biography. Adrian C. Laing.

- ↑ Obituary of R. D. Laing by Joseph Berke; Daily Telegraph, 25 August 1989.

- 1 2 Beveridge, A. (2011) Portrait of the Psychiatrist as a Young Man: The Early Writing and Work of R. D. Laing, 1927-1960 Oxford University Press

- ↑ Kynaston, David (2009). Family Britain 1951-7. London: Bloomsbury. p. 97. ISBN 9780747583851.

- ↑ Turnbull, Ronnie; Beveridge, Craig (1988), "R.D. Laing and Scottish Philosophy", Edinburgh Review, 78–9: 126–127, ISSN 0267-6672

- ↑ Mad to be Normal: Conversations with R.D. Laing [Paperback]

- ↑ Mad to be Normal: Conversations with R.D. Laing [Paperback]

- ↑ Itten, Theodor, The Paths of Soul Making, archived from the original on 16 October 2007, retrieved 17 October 2007

- ↑ "Kingsley Hall". Philadelphia Association. Archived from the original on 9 May 2008. Retrieved 13 September 2008.

- ↑ Axel Jensen. Axel Jensen, Livet sett fra Nimbus ("Life as seen from Nimbus"): a biography as told to Petter Mejlænder (in Norwegian). Oslo: Norway: Spartacus forlag (Spartacus Publishing).

- ↑ Laing, Adrian (1994). R.D. Laing: A Life. London: HarperCollinsPublishers. pp. 165–166. ISBN 0-00-638829-9.

- ↑ Miller, Russell (12 April 2009), "RD Laing: The abominable family man", The Sunday Times, London, retrieved 8 August 2011

- ↑ Mad to be Normal: Conversations with R. D. Laing ISBN 1853433950[Paperback]

- ↑ Obituary of R. D. Laing by Joseph Berke; Daily Telegraph, 25 August 1989

- ↑ University of Glasgow Special Collection: Document Details, retrieved 17 October 2007

- ↑ Burston, Daniel (1998), The Wing of Madness: The Life and Work of R. D. Laing, Harvard University Press, p. 145, ISBN 0-674-95359-2

- ↑ Laing, Adrian (1 June 2008), "Dad solved other people's problems — but not his own", The Guardian, London, retrieved 22 May 2010

- ↑ Laing Society Archived 2 March 2007 at the Wayback Machine.

- ↑ His third daughter Karen was born in Glasgow in 1955 and is now a pracitising psychotherapist.Burston, Daniel (1998), The Wing of Madness: The Life and Work of R. D. Laing, Harvard University Press, p. 125, ISBN 0-674-95359-2

- ↑ Day, Elizabeth (1 June 2008). "Dad solved other people's problems — but not his own". The Guardian. London. Retrieved 22 May 2010.

- ↑ Bateson, G., Jackson, D. D., Haley, J. & Weakland, J., 1956, Toward a theory of schizophrenia. (in: Behavioral Science, Vol.1, pp. 251-264)

- ↑ Laing, R.D. (1965). The Divided Self. Pelican. pp. 41–43. ISBN 0-14-020734-1.

- ↑ "The Unofficial R.D.Laing Site - Biography". Archived from the original on 7 February 2002. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "Various - Miniatures (A Sequence Of Fifty-One Tiny Masterpieces Edited By Morgan Fisher) (Vinyl, LP, Album)". discogs.com. Discogs. Retrieved 4 October 2016.

- ↑ "The Philadelphia Association: Philosophical Perspective". Philadelphia Association. Archived from the original on 6 December 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ Coltart, Nina (1990). "ARBOURS ASSOCIATION 20TH ANNIVERSARY LECTURE". British Journal of Psychotherapy. p. 165. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ "Existential Counselling and Psychotherapy, and the New School". New School of Psychotherapy and Counselling. Archived from the original on 26 December 2008. Retrieved 7 September 2008.

- ↑ "RD Laing in the 21st Century Symposium". RD Laing in the 21s Century Symposium. Retrieved 30 July 2018.

- ↑ Cooke, Lez "BFI Screenonline: Loach, Ken (1936-) Biography", accessed 7 July 2011.

- ↑ IMDB "Birth with R.D. Laing", accessed 7 July 2011.

- ↑ "Current Features - Mad to be Normal". www.gizmofilms.com. Gizmo Films. Retrieved 31 January 2016.

- ↑ Psychoanalytic Electronic Publishing. Retrieved on 16 October 2008

- ↑ Original is located in the R.D. Laing Special Collection, Glasgow University Library. See also 'Prenatal Patterns in Postnatal Life' (1978) by R.D. Laing.

Further reading

- Boyers, R. and R. Orrill, Eds. (1971) Laing and Anti-Psychiatry. New York: Salamagundi Press.

- Burston, D. (1996) The Wing of Madness: The Life and Work of R. D. Laing. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Burston, D. (2000) The Crucible of Experience: R.D. Laing and the Crisis of Psychotherapy. Cambridge, MA: Harvard University Press.

- Clay, J. (1996) R.D. Laing: A Divided Self. London: Hodder & Stoughton.

- Collier, A. (1977) R.D. Laing: The Philosophy and Politics of Psychotherapy. New York: Pantheon.

- Evans, R.I. (1976) R.D. Laing, The Man and His Ideas. New York: E.P. Dutton.

- Friedenberg, E.Z. (1973) R.D. Laing. New York: Viking Press.

- Itten, T. & Young, C. (Ed.) (2012) R. D. Laing - 50 Years since The Divieded Self. Ross-on-Wye, PCCS-Books

- Miller, G. (2004) R.D. Laing. Edinburgh: Edinburgh University Press.

- Laing, A. (1994) R.D. Laing: A Biography. New York: Thunder's Mouth Press.

- Kotowicz, Z. (1997) R.D. Laing and the Paths of Anti-Psychiatry. London: Taylor & Francis.

- Mullan, B., Ed. (1997) R.D. Laing: Creative Destroyer. London: Cassell & Co.

- Mullan, B. (1999) R.D. Laing: A Personal View. London: Duckworth.

- Raschid, S., Ed. (2005) R.D. Laing: Contemporary Perspectives. London: Free Association Books.

External links

| Wikiquote has quotations related to: R. D. Laing |

| Wikimedia Commons has media related to R. D. Laing. |

- The International R.D. Laing Institute (Switzerland)

- Biography at The Society for Laingian Studies

- Special Issue of Janus Head, Edited by Daniel Burston

- The Philadelphia Association

- Historical documents including correspondence with Gregory Bateson

- RD Laing: The Abominable Family Man from The Sunday Times

- Life before Death - 1978 album of sonnets and other poems performed by R. D. Laing to an original musical score

- Leo Matos and R. D. Laing: Transpersonal Psychology on YouTube: St Görans Lecture, Stockholm, 10 February 1982.

- R. D. Laing at Find a Grave