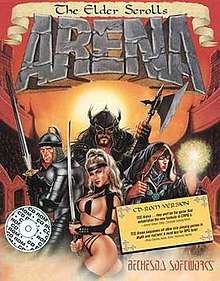

The Elder Scrolls: Arena

| The Elder Scrolls: Arena | |

|---|---|

| |

| Developer(s) | Bethesda Softworks |

| Publisher(s) | Bethesda Softworks |

| Director(s) | Vijay Lakshman |

| Producer(s) | Vijay Lakshman |

| Designer(s) | Vijay Lakshman |

| Programmer(s) | Julian Lefay |

| Composer(s) | Eric Heberling |

| Series | The Elder Scrolls |

| Platform(s) | MS-DOS |

| Release | |

| Genre(s) | Action role-playing |

| Mode(s) | Single-player |

The Elder Scrolls: Arena is an epic fantasy open world action role-playing video game developed and published by Bethesda Softworks and released in 1994 for MS-DOS. It is the first game in The Elder Scrolls series. In 2004, a downloadable version of the game was made available free of charge as part of the 10th anniversary of The Elder Scrolls series.

Like its sequels, Arena takes place on the continent of Tamriel, complete with wilderness, dungeons, and a spell creation system that allows players to mix various spell effects.

Gameplay

.png)

The game is played from a first-person perspective.[2] Melee combat is performed by right-clicking the mouse and dragging the cursor across the screen to attack as if swinging a weapon. Magic is used by cycling through a menu found by clicking the appropriate button on the main game screen, then clicking the spell to be used, and its target.

At around 6 million square kilometers, the game world is considerably larger than that of The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, IV: Oblivion and V: Skyrim. This is achieved by combining randomly generated content and specifically designed world spaces to create a realistic and massive wilderness, where one may find inns, farms, small towns, dungeons, and other places of interest. The towns contain developer-designed buildings and shops, but the order in which these appear and their names are randomized. There are several hundred dungeons and 17 specially designed dungeons for the main quest. Unlike later instalments in the series, Arena has no set overworld (the wilderness constantly generates), so the player must use the quick travel feature to get from one area of the world to another; it also takes a long time to walk from place to place due to the size of the world, which means walking to a nearby town could frequently take ten hours of real time and walking to distant areas could take several days.

Arena is notable for being one of the first games to feature a realistic day/night cycle, where at sunset shops close and people clear the streets before the monsters arrive and roam around until morning. This soon became a staple feature of most open-world games.

In addition to the main quest which is completed by beating all seventeen dungeons and finding pieces of the staff, small side quests also appear. These are often found by asking around town for rumours. These quests are usually very simple, such as delivering a parcel or defeating a randomly generated dungeon.

Arena has been noted for its tendency to be unforgiving towards new players. It is easy to die in the starting dungeon, as powerful enemies can be encountered if the player lingers too long. This effect gradually disappears as the player becomes more powerful and more aware of the threats that loom everywhere. Ken Rolston, lead designer of The Elder Scrolls III: Morrowind, says he started the game at least 20 times, and only got out of the beginning dungeon once.[3]

Plot

At the beginning of the game in the 389th year of the third era, Emperor Uriel Septim VII summons his advisor and Imperial Battlemage Jagar Tharn over concerns of betrayal from within the court. It transpires that his concerns were justified as Tharn is revealed to be the traitor and then proceeds to trap the Emperor in another dimension and take his place as emperor in magical disguise. During his usurpation of the throne, Tharn is witnessed by Septim's apprentice Ria Silmane who attempts to warn the Elder Council. Unable to corrupt her he opts to murder her instead. Tharn then summons demon minions to replace the Emperor's Guard and sends their leader Talin Warhaft (the player character) to his death in the Imperial Dungeons.

Ria takes an incorporeal form and is able to hold herself together long enough to inform Talin of what has happened and to instruct the player how to escape from slow death in the dungeons - this first dungeon is infamously difficult to survive. Past that point, she lacks the power to manifest physically and appears to the player during dreams. She creates a key to allow Talin to escape and teleports him to a different province through a Shift Gate.

The player is informed that the only way to stop Tharn is to get hold of the Staff of Chaos which holds his lifeforce. This staff has been split by Tharn into many fragments. Each time one is found, Ria appears to the player the next time they rest, in order to provide the general location of the next fragment. At the end of the quest in 3E 399 (a decade after the start of the game), Talin finds the final piece and reassembles the staff. This does not, however, destroy Tharn, as there is a final piece of the staff that both Ria and Talin were unaware of: the jewel, located in the Imperial Palace. The player battles through the palace to fight finally with Tharn, who he proceeds to melt by bringing the staff into contact with the jewel. This also creates a portal to the other dimension, rescuing the Emperor and his general. They both thank the player and makes the player the Eternal Champion as reward.

Development

Background

Designer Ted Peterson recalls the experience: "I remember talking to the guys at SirTech who were doing Wizardry: Crusaders of the Dark Savant at the time, and them literally laughing at us for thinking we could do it."[4] Ted Peterson worked alongside Vijay Lakshman as one of the two designers of what was then simply Arena, a "medieval-style gladiator game".[4][5]

Staff

Peterson, Lakshman and Julian LeFay were those who, in Peterson's opinion, "really spear-headed the initial development of the series."[4] Game journalist Joe Blancato credits company co-founder Chris Weaver with the development: "If Weaver had a baby, Arena was it, and it showed." During the development of Arena, Todd Howard, later Executive Producer of Oblivion and lead designer on Skyrim and Fallout 3 and 4, joined Bethesda, testing the CD-ROM version of Arena as his first assignment.[6] Ted Peterson had joined the company in 1992, working assignments on Terminator 2029, Terminator Rampage, and Terminator: Future Shock, as well as other "fairly forgettable titles".[4]

Influences

Peterson, Lakshman and LeFay were longtime aficionados of pencil-and-paper role-playing games,[4] and it was from these games that the world of Tamriel was created.[5] They were also fans of Looking Glass Studios' Ultima Underworld series, which became their main inspiration for Arena.[4]

The influence of Legends of Valour, a game Ted Peterson describes as a "free-form first-person perspective game that took place in a single city", has also been noted.[4][5] Peterson, asked for his overall comment on the game, replied "It was certainly derivative ...". Aside from the fact that Bethesda had made Arena "Much, much bigger" than other titles on the market, Peterson held that the team "[wasn't] doing anything too new" in Arena.[4]

Design goals

Initially, Arena was not to be an RPG at all. The player and a team of his fighters would travel about a world fighting other teams in their arenas until the player became "grand champion" in the world's capital, the Imperial City.[5] Along the way, side quests of a more role-playing nature could be completed. As the process of development progressed, however, the tournaments became less important and the side quests more.[4] RPG elements were added to the game, as the game expanded to include the cities outside the arenas, and dungeons beyond the cities.[5] Eventually it was decided to drop the idea of tournaments altogether, and focus on quests and dungeons,[4] making the game a "full-blown RPG".[5]

The original concept of arena combat never made it to the coding stage, so few artifacts from that era of development remain: the game's title, and a text file with the names of fighting teams from every large city in Tamriel, and a brief introduction for them.[7] The concept of travelling teams was eventually left aside as well because the team's decision to produce a first-person RPG had made the system somewhat less fun.[5]

Although the team had dropped all arena combat from the end game, because all the material had already been printed up with the title, the game went to market as The Elder Scrolls: Arena. The team retconned the idea that, because the Empire of Tamriel was so violent, it had been nicknamed the Arena. It was Lakshman who came up with the idea of "The Elder Scrolls", and though, in the words of Ted Peterson, "I don't think he knew what the hell it meant any more than we did",[4] the words eventually came to mean "Tamriel's mystical tomes of knowledge that told of its past, present, and future."[5] The game's initial voice-over was changed in response, beginning: "It has been foretold in the Elder Scrolls ..."[4]

Release

The game was originally due to release on Christmas Day 1994 but it was then earlier released on November 28 before the Christmas rush. The misleading packaging further contributed to distributor distaste for the game, leading to an initial distribution of only 3,000 units—a smaller number even, recalls Peterson, than the sales for his Terminator: 2029 add-on. "We were sure we had screwed the company and we'd go out of business."[4] However, PC Gamer US reported in late 1995:

"Word-of-mouth did the trick. The game-starved RPG fans looked at Arena, loved it, and spread the word. Sales rocketed; awards and accolades rained down. Today, more than eighteen months after publication, the game is still selling and still being played avidly."[8]

Arena was originally released on CD-ROM and 3.5" floppy disk. The CD-ROM edition is the more advanced, featuring enhanced speech for some characters and CGI video sequences. In late 1994, Arena was re-released in a special "Deluxe Edition" package, containing the CD-ROM patched to the latest version, a mousepad with the map of Tamriel printed on it, and the Codex Scientia, an in-depth hint book.

The version that was released as freeware by Bethesda Softworks in 2004 is the 3.5" floppy disk version, not the CD-ROM edition. Newer systems may require an emulator such as DOSBox to run it, as Arena is a DOS-based program.[9]

Reception

| Reception | ||||||||

|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|---|

| ||||||||

| ||||||||

When previewing the game in December 1993, Computer Gaming World noted Arena's "huge world split into nine provinces", many races and terrains, NPC interactions, and absence of level limits. The magazine stated that the game had sophisticated graphics "without forgetting the lessons of the past in terms of game design" or being "more like [console] action games", citing similarities with Ultima IV, Wasteland, Dragon Wars, and Darklands.[13] The magazine in April 1994 said that Arena "looks like a cross between Ultima Underworld and Might and Magic: World of Xeen", with both depth and sophisticated 3D graphics. It surmised "This may be the 'biggest' world, in terms of game play, that will reach store shelves this year", with a "rich and compelling" storyline and setting.[14] The magazine's Scorpia in May 1994 noted the game's "many, many, many side quests". She liked the combat ("the most natural way of fighting that I've seen in a first-person game"), magic system, world detail, and character creation, but disliked Arena's instability "even with three patches so far" and insufficient travel time to finish quests. Scorpia complained that "in a game of this size, everything eventually becomes mechanical and repetitious", including towns, conversation trees, quests, and enemies, reporting that "Everything is isolated, and there is no sense of a coherent whole here". She said that "Arena ... is too big to offer real variety, and thus becomes no more than a very sophisticated dungeon crawl with minimal plot", but hoped that Bethesda would apply to Elder Scrolls "a tightening of the code, a little polishing up of the basic engine, a little scaling back of the size, and the inclusion of some real role-playing elements ... with a solid storyline. These are well within Bethesda's abilities".[15] The next month she reported that another patch had been released and a fifth was being developed ("Obviously, the game was released far, far too soon, with less than adequate playtesting"). She advised players to store their save games after finishing Arena, as "I expect that the next game will show quite a few improvements over the initial entry in the series".[16]

In PC Gamer US, Bernie Yee summarized Arena as a "stunning technological achievement; give this game a better storyline, and you might have the best FRP ever designed."[10] Later that year, the magazine named Arena the 18th greatest game of all time. The editors praised it as "next-generation role-playing that will satisfy both newcomers and veterans alike."[17] The game was a runner-up for PC Gamer US's 1994 "Best Role-playing Game" award, losing to Realms of Arkania: Star Trail.[18]

Barry Brenesal of Electronic Entertainment wrote, "While The Elder Scrolls, Chapter One: Arena has nothing revolutionary to offer in role-playing fantasy, it is nevertheless a worthwhile game for the sheer depth of its quest capabilities that far outnumber the competition."[11]

Arena won Computer Gaming World's 1994 "Role-Playing Game of the Year" award, beating Wolf, Star Trail, Ravenloft: Strahd's Possession and Superhero League of Hoboken. The editors hailed Arena as "a breakthrough game".[12]

Despite the formidable demands the game made on players' machines,[19] the game became a cult hit.[6] Evaluations of the game's success vary from "minor"[4] to "modest"[19] to "wild",[6] but are unvarying in presenting the game as a success. Game historian Matt Barton concludes that, in any case, "the game set a new standard for this type of CRPG, and demonstrated just how much room was left for innovation."[19]

References

- ↑ http://www.bethblog.com/2014/03/25/20-years-of-elder-scrolls/

- ↑ "The Elder Scrolls: Arena". IGN. Retrieved September 15, 2008.

- ↑ Rolston, Ken (June 16, 2007). "Most Memorable Elder Scrolls Moments". Bethesda Softworks. Archived from the original on March 7, 2008.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 9 10 11 12 13 14 "Ted Peterson Interview I". Morrowind Italia. April 9, 2001. Archived from the original on July 21, 2013. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- 1 2 3 4 5 6 7 8 "Arena - Behind the Scenes". The Elder Scrolls 10th Anniversary. Bethesda Softworks. 2004. Archived from the original on May 9, 2007. Retrieved June 8, 2007.

- 1 2 3 Blancato, Joe (February 6, 2007). "Bethesda: The Right Direction". The Escapist. Retrieved June 1, 2007.

- ↑ "Go Blades!". The Imperial Library. Retrieved October 18, 2010.

- ↑ Trotter, William R. (November 1995). "Bethesda Softworks: The Little Giant". PC Gamer US. 2 (11): 92–94, 96, 98.

- ↑ "Bethesda Softworks celebrates Elder Scroll's 10th". GameSpot. April 7, 2007. Retrieved April 8, 2008.

- 1 2 Yee, Bernie (May–June 1994). "The Elder Scrolls, Volume 1: Arena". PC Gamer US (1): 70, 71.

- 1 2 Brenesal, Barry (June 1994). "The Elder Scrolls, Chapter One: Arena". Electronic Entertainment (6): 100.

- 1 2 "The Computer Gaming World 1995 Premier Awards". Computer Gaming World. No. 130. May 1995. pp. 35, 36, 38, 40, 42, 44.

- ↑ Wilson, Johnny L. (December 1993). "Fresh Blood In The Role-Playing Arena". Computer Gaming World. pp. 28, 30. Retrieved March 29, 2016.

- ↑ "Taking A Peek". Computer Gaming World. April 1994. pp. 174–180.

- ↑ Scorpia (May 1994). "Enter The Gladiator!". Scorpion's View. Computer Gaming World. pp. 102–106.

- ↑ Scorpia (June 1994). "Return to Arena". Scorpion's View. Computer Gaming World. pp. 68–72.

- ↑ Staff (August 1994). "PC Gamer Top 40: The Best Games of All Time". PC Gamer US (3): 32–42.

- ↑ Staff (March 1995). "The First Annual PC Gamer Awards". PC Gamer. 2 (3): 44, 45, 47, 48, 51.

- 1 2 3 Barton, Matt (April 11, 2007). "The History of Computer Role-Playing Games Part III: The Platinum and Modern Ages (1994–2004)". Gamasutra. Retrieved June 8, 2007.